Posts Tagged ‘Movie Time’

Watching the world burn: The incongruous politics of ‘The Dark Knight’

July 23, 2018Batman isn’t the star of The Dark Knight. That’s plain old conventional wisdom at this point. But Christian Bale’s foil, Heath Ledger’s iconic Joker, isn’t the star either. Not really. Nor is it Harvey Dent, Gotham’s white knight, or Jim Gordon, the archetypal honest cop, or Rachel Dawes, the doomed idealist, or Lucius Fox, the steady hand, or Alfred, the faithful servant.

The real star of The Dark Knight, Christopher Nolan’s cinematic superhero landmark, is the concept of ethical behavior — and the performance stinks.

Written by Nolan and his brother Jonathan, who’s currently taking an equally high-minded and heavy-handed approach to ethical issues in Westworld, The Dark Knight is fixated on the opposition between right and wrong, order and chaos, and hope and despair, all to a degree no other superhero movie as come close to touching. While most costumed-and-caped adventures are content to let such issues stay subtextual, with the superpowered slugfests between heroes and villains serving as a metaphor for these underlying conflicts, The Dark Knight spins them into the whole plot.

Who’s a better example for Gotham City to follow out of its long-standing hell of crime and corruption: Dent, an elected official who obeys the will of the people and observes the rule of law, or Batman, a self-appointed vigilante who follows no rules but his own? Who’s right about the nature of humanity, Batman, who wants to serve as a symbol to inspire the stifled good he believes exists within everyone, or the Joker, who wants to prove that all systems — from organized crime to democracy — are just pancake makeup applied to a scarred mass of nihilism and brutality? To stave off chaos, is it permissible to inflict order on the whims of one man?

The answers the film wants us to take away are obvious. Dent, not Batman, is the hero Gotham needs; Batman, not the Joker, sees the hearts of his fellow citizens clearly; even in the face of overwhelming danger, the power to stop it must be checked before it becomes just as dangerous.

These aren’t the answers that the film actually provides. By emerging just before the dawn of Barack Obama’s presidency, when the general consensus in America seemed sick and tired of the unending and overreaching War on Terror as it was of the terrorists said war was ostensibly designed to fight, The Dark Knight tapped into a national mood — the film repeatedly describes the Joker’s actions as “terrorism” — and sent the audience home with a positive message. But the film itself is a hopeless political muddle, constantly trying to have its liberty vs. security, order vs. anarchy, vigilantism vs. legitimacy cake and eat it, too.

The only good online fandom left is ‘Dune’

July 11, 2018In the contemporary internet sense, the Dune discourse is wild and wide open, without the warring-camp, protect it at all costs mentality that plagues so many other geek-culture staples. If you say “The spice must flow,” you aren’t risking hours of replies from angry pedants the way you might if, oh I don’t know, you point out that in Justice League, Aquaman’s trident (from the Latin for “three teeth”) has five points instead of three. Unless you try very hard, you’re also unlikely to encounter anyone complaining that Dune has been ruined by SJWs and soyboys, or that critics who like it have been bought off by that sweet De Laurentiis money. Yet it’s still a sprawling invented world that provides you with all the esoterica and trivia and map-reading and jargon-slinging joy of any other. You can get stoned and stay up until the wee hours making dank Duncan Idaho memes with your friends, or with no one at all, completely unmolested.

And perhaps I’m going out on a limb here, but based on the source material and the filmmakers historically associated with adapting it — including Villeneuve, whose Blade Runner movie gives us a solid recent point of comparison — Dune-iverse phrases like “Tleilaxu ghola” or “prana-bindu training” or “He is the Kwisatz-Haderach” are never gonna reach “Infinity Stones” or “Ten points for Gryffindor” or “A Lannister always pays his debts” levels. Anyone who’s seen the very real Dune coloring and activity books, which look like an elaborate prank, can attest to how tough it is to boil this stuff down to four-quadrant consumability. It’s true that the books are bestsellers, but so is the comparable work of Jeff VanderMeer, author of Annihilation, which became a well-regarded science-fiction film that nevertheless won’t be getting Happy Meal tie-ins anytime soon.

No matter how much Lynch’s version trends upward in critical estimation, no matter how (or if) Villeneuve’s new version pans out, this is just not a franchise that’s scalable in the Transformers or Harry Potter way. It’s too dense, too weird. It smells like sun-bleached library paperbacks. Which, by the way, are the only form in which Dune has been successfully franchised, in the form of sequels co-authored by workmanlike SFF writer Kevin J. Anderson and Herbert’s son Brian. Dune references signal shared knowledge to those in the know, and that’s about it. Dune fandom is an un-fandom.

More than anything else, this is what makes immersion in Dune such an attractive prospect. Paul Atreides found anonymity, friendship, and freedom in the secret ways of the unconquerable Fremen desert tribes (Fremen, “free men,” get it?); his life after that point was a prolonged struggle to export that sense of freedom to others. Consciously or not, Herbert himself summed up the promise of Paul’s life in his introduction to New World or No World, repackaging it as a plan for the survival of the species and the planet we live on.

“The thing we must do intensely is be human together,” he wrote. “People are more important than things. We must get together. The best thing humans can have going for them is each other. We have each other. We must reject everything which humiliates us. Humans are not objects of consumption. We must develop an absolute priority of humans a head of profit — any humans ahead of any profit. Then we will survive. Together.” Dune is one small, goofy, vital way of sharing something wonderful with each other, and with nothing and no one else.

For my debut at The Outline I wrote about Dune, the nerdiest popular thing you can enjoy without feeling like a corporate shill or a footsoldier in some weird fandom war. I went real long and real deep, so please take a look!

The 50 Greatest Comedies of the 21st Century

June 11, 201826. ‘Wet Hot American Summer’ (2001)

Meet the only film on this (or any other) list in which a deranged Vietnam veteran played by Law & Order: SVU’s Christopher Meloni learns valuable life lessons from a talking can of vegetables that can suck its own dick. (“And I do it a lot.”) With a gaggle of alums from the influential sketch comedy group the State both in front of and behind the camera – and a cast of soon-to-be superstars including Bradley Cooper, Amy Poehler, Elizabeth Banks and Paul Rudd – this send-up of raunchy Reagan-era teen comedies has an anything-for-a-laugh approach that actually gets laughs every time. This one-time cult curiosity has since spawned two Netflix spinoff series … as well as a legendary DVD audio commentary track that just adds extra fart sounds.

I contributed a pair of write-ups to Rolling Stone’s list of the best comedies of the century so far, featuring the usual murderers’ row of writers. Enjoy!

‘The Last Jedi’ Is the Worst ‘Star Wars’ Movie, but Its Haters and Stans Are Both Wrong About Why

June 3, 2018Star Wars: The Last Jedi mind-tricked its audience. As if in homage to the galaxy in which the film is set—divided as it is between the Dark Side and the Light—Rian Johnson’s 2017 installment in the saga sparked the most preposterously binary set of responses to a franchise film in recent memory. Read about this continuation of the Disney-owned sequel trilogy (begun and soon to be ended by J.J. Abrams) and you’ll quickly feel the pull of two opposing Forces, demanding allegiance. Broadly speaking: Is it a heartbreaking work of staggering genius that redeems the Star Wars concept by having the courage to toss it aside, or is it a million childhoods suddenly crying out in terror and then suddenly silenced…by incipient white genocide?

I say it’s neither, and man am I tired of having to say it, but before I see Solo I’ll give it one last shot. The Last Jedi is my least favorite Star Wars movie by far, but not for any of the reasons most of its detractors cite, nor for those against which its champions array their defenses. The misogynistic bigots whose response to the film is essentially “Why isn’t there a White History Month” will have to settle for running all three branches of government; they won’t get me to agree that a story driven by vivid and charismatic characters played by natural-born movie stars Daisy Ridley, John Boyega, Oscar Isaac, Adam Driver, and Domnhall Gleeson—the best things either TLJ or its immediate predecessor The Force Awakens have going for them—represent the collapse of the West. Nor am I going to agree to their terms of debate the way so many proponents of the film have, acting as though hidebound nostalgia at best and bald-faced reactionary fury at worst are the only reasons to take issue with this movie. The Last Jedi has its moments, but its faults are many—and too often obscured by the Sith vs. Jedi nature of the debate surrounding it.

Right up front, let’s forget the idea that TLJ represents some bold act of iconoclasm—a creatively courageous attempt to unmoor the franchise from nostalgia. There’s a substratum of angry nerds who think believe this and hate it, and a separate group of critics and critic-adjacent people online who believe this and love it. I really don’t know how either group comes to this conclusion about what is, after all, the ninth Star Wars movie. It’s got dark lords and chosen ones, lightsabers and Star Destroyers, cute aliens and cute droids, you name it. Rey’s parentage may have been rendered a non-issue (in a desultory rip-off of the mirror sequence from The Never-ending Story, but whatever), but Kylo Ren is still the biological descendent of the main characters from both of the previous trilogies. And this is the guy—the bad guy, might I add—who utters the “let the past die” mantra so many critics and detractors alike seem to have taken to heart as the film’s mission statement. Again, this is the ninth Star Wars movie. If you want to let the past die, go watch or make a film that doesn’t co-star characters who debuted 40 years earlier.

To the extent that writer-director Rian Johnson did wipe the slate clean, the effect was not a healthy one. Dispensing with the pattern established by all the other movies, Johnson resumes the action right where The Force Awakens leaves off. Leia, Poe, Finn, C-3PO, BB-8, and the rest of the Resistance core are still on their home base from the previous film; so little time has elapsed that they’re still waiting for the First Order to show up and chase them out of there when the movie begins. Elsewhere, Rey and Luke’s storyline resumes mid-conversation. Because of this, our first images of our heroes take place in places we’ve already seen, rather than dropping us head-first into new ones—not even the familiar desert/forest/ice archetypes of The Force Awakens, which were at least different planets than the ones from the original trilogy, if not different types of planets.

The bulk of the story takes place on Luke’s island, a couple of spaceships, and finally a single patch of a desert planet that simply substitutes salt for sand and adds a little red dust for flair. The plot concerns Rey trying and failing to convince Luke to get up off his ass and Kylo Ren and General Hux picking off Resistance ships one by one, Battlestar Galactica–style (to put the resemblance kindly, though if you called it a knockoff I wouldn’t object). Mysteries aren’t so much solved as canceled: Rey’s parents are nobodies (a theoretically interesting idea delivered in perfunctory fashion) and the mysterious Supreme Leader Snoke gets jobbed out before displaying a single interesting characteristic except being unusually tall and having cool red wallpaper. The film ends with the characters hiding in an abandoned garage some guy’s trying to break into, pretty much.

In short, this is the first Star Wars movie in which the world feels smaller at the end of the movie than it did at the beginning. It’s an attritional film, one that whittles away until only a tiny fragment remains. The manic thrill of discovery and creation that made the original trilogy so culture-changingly compelling—and which makes the much-maligned prequel trilogy, which you can read persuasive defenses of here and here, a gloriously weird work of art on the Speed Racer level if nothing else—is almost entirely absent. (Almost: the trip made by Finn and his new ally Rose to that casino planet has that wild and woolly feeling to it, which paradoxically may be why people dislike it; Leia’s Force-enabled spacewalk is a poor substitute for getting to see her with a lightsaber in her hand but it’s still good audience-rousing fun; the Porgs, of course, are perfection. But that’s thin gruel to spread across two and a half hours of running time.)

This is the first half of my lengthy essay for Decider on why I don’t like The Last Jedi. I just got so sick of seeing the debate, both pro and con sides, framed entirely in terms set by bigots or “my childhood!!!” types, and wanted to open up other lines of criticism and inquiry. Click here to read the rest.

The Boiled Leather Audio Hour Episode 73!

March 30, 2018Starship Troopers and Rambo

Come one, you apes! You wanna live forever? We sure hope not, because when you’re pushed, killing’s as easy as breathing. And so is listening to Sean and Stefan discus two of the most violent — and morally complex — action movies of the modern era, Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers and Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo. Made in 1997 and 2008 respectively, these films use satire (in the former case) and spectacle (in the latter) to probe the gaping wounds of fascism, war, war movies, and the act of killing. If, like us, you’re an admirer of how A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones use epic-battle tropes to interrogate the horrors of war, this discussion of two strange films that do the same is for you. Enjoy…?

Additional links:

Stefan’s essay on Starship Troopers (Patreon subscribers only).

Our Patreon page at patreon.com/boiledleatheraudiohour.

Our PayPal donation page (also accessible via boiledleather.com).

Stallone’s ‘Rambo’: The Strangest Sequel Ever Made

March 5, 2018John Rambo spent the 1980s knifing, booby-trapping, and exploding his way into the American consciousness. But to resurrect this killer of a character for the 2000s, Sylvester Stallone dug deep into the heart of his hero… and dear God, that heart was dark.

Released in early 2008 to solid box-office success and minimal critical favor, Rambo promised a back-to-basics approach to Stallone’s hit action franchise, just as 2006’s acclaimed, heartwarming Rocky Balboa had done for The Italian Stallion. Stallone even planned to title the movie John Rambo to make the comparison even more direct, and wound up using that title for the film’s longer, more character-driven extended cut. But while the fourth and final film in the Rambo franchise gave Sly’s troubled Vietnam veteran a happy ending at last — its closing shot shows the 60-year-old killing machine returning to his family farm in Arizona for the first time in decades — it also gives us a character to fear, not root for. This evolution of Rambo as a character and mainstream action franchise, in turn, reveals uncomfortable, disturbing truths about the United States, and after a recent revisit, suggests that our own violent history should be treated with far more nuance than unquestioned cheerleading.

Set in the killing fields of Burma, Rambo is a brutal and bracing revisionist take on a hero whose name is synonymous with mindless action-movie excess, from the man who helped craft that excess in the first place. Yet it’s precisely because of its unprecedented savagery that the film feels truer to John Rambo’s roots than either of the sequels that preceded it: the movie, this time directed by Stallone, takes the philosophical tensions and fear of warfare present in the franchise since its politically fraught initial installment, loads them into a machine gun, and fires them directly at our collective face. Using all the tools at an old Hollywood hand’s disposal, it reflects the national mood by depicting its angry American as both suffering and inflicting trauma, in as traumatizing a manner as big-budget action movies have ever attempted.

Three thousand words on Rambo for Thrillist? Don’t mind as I do. I’m proud of this piece on one of the most viscerally disturbing and structurally odd mainstream action movies ever made.

The 10 Best (and Worst) Best Song Oscar–Winners of All Time

March 1, 2018Best: “Streets of Philadelphia” (‘Philadelphia,’ 1993)

Like “Shaft” shaking up the saccharine sounds of the 1970s, Bruce Springsteen’s sad, sparse contribution to the soundtrack of Jonathan Demme’s AIDS-crisis drama Philadelphia is a bracing break from the Best Song norm of its era. The lyrics are one the Boss’s most haunting portrayals of loneliness and abandonment (“I was bruised and battered, I couldn’t tell what I felt / I was unrecognizable to myself”); he recorded the song alone in his home studio with a synthesizer and a drum machine, and you can hear the isolation in every note. (The only down side to the song’s victory: Neil Young’s even more devastating contribution to Demme’s movie, titled “Philadelphia,” had to lose.)

Worst: “Can You Feel the Love Tonight” (‘The Lion King,’ 1994)

It didn’t have to be this way. When Disney’s big animated comeback The Little Mermaid upended the Eighties’ string of Top 40 Best Song winners in 1989, it did so not with a ballad (although “Part of Your World” is one of the studio’s best) but with the calypso jam “Under the Sea.” Beginning with 1991’s Oscar for “Beauty and the Beast,” though, the category became a cartoon-ballad free-for-all, with live-action winners mostly following suit. The result is one of the dreariest, schmaltziest runs in the award’s history, and they don’t come much goopier than Elton John and Tim Rice’s love song for lions. Pro tip: “Funeral for a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding” is twice as long but about 40 times as awesome.

I had a grand old time writing about the best and worst Best Song Oscar winners of all time for Rolling Stone. These kinds of pieces are a blast to write, since you get to cover so much territory and study how values change over time.

The Boiled Leather Audio Moment #16!

January 18, 2018Moment 16 | Sean vs. Mad Max: Fury Road & The Fifth Element

It’s another surprise Sean solo edition of BLAM! This time, Sean’s tackling two movies he dislikes, at the request of listener Jonathan Mauro: George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road and Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element. What’s your illustrious co-host’s beef against these two much-beloved blockbuster sci-fi/action hits? Subscribe for just $2/month and find out!

The 100 Greatest Movies of the Nineties

July 13, 201749. Heavenly Creatures (1994)

Before Peter Jackson took us all to Middle-earth, he brought moviegoers to the mad world of two troubled teenagers – a fictional universe every bit as engrossing as J.R.R. Tolkien’s, but far more romantic and lethal. Based on a true-crime story, the film depicts pre-stardom Kate Winslet and Melanie Lynskey as Pauline Parker and Juliet Hume, two New Zealand teenagers whose BFF-ship blossoms first into love, then madness and ultimately murder. Jackson’s kinetic camera captures the rapturous swirl of teenage dreams before plunging us into its brutal, bloody endpoint. It’s a beautiful dark twisted fantasy. STC

I wrote about Natural Born Killers, Heavenly Creatures, and The Blair Witch Project for Rolling Stone’s list of The 100 Greatest Movies of the ’90s. My editor David Fear assembled an absolute murderers’ row of writers for this thing — it’s a real treat.

The Boiled Leather Audio Hour Episode 64!

June 30, 2017Children of Men (A Patreon Production)

The Boiled Leather Audio Hour goes dystopian this month! By the special request of our Patreon supporter Jason, who earned the right to choose a topic for the podcast by subscribing at the $50 level, Sean & Stefan are taking a deep dive into the world of Children of Men, director Alfonso Cuarón’s gripping 2006 political science-fiction film. Starring Clive Owen and Julianne Moore and set in a near future where the world has been rocked by an infertility epidemic that has completely ended all childbirths for 18 years and counting, the movie is striking both for its technical virtuosity, particularly during its white-knuckle action sequences, and its emphasis on very human cruelty and empathy. How does its technical prowess affect its message? Where does the storytelling and imagery succeed, and where does it falter? What does its bleak yet ultimately optimistic vision of the future portend for our own grim present? We’ll do our best to answer those questions. Needless to say, spoilers abound!

Additional links:

Abraham Riesman’s article on the making of the film for Vulture.

Our Patreon page at patreon.com/boiledleatheraudiohour.

Our PayPal donation page (also accessible via boiledleather.com).

“Under the Skin” Is the Best Horror Movie You’ve Never Seen

May 27, 2015Like comedy and pornography, horror is a practical art with a concrete aim; it exists to frighten. This utilitarian aspect makes horror a genre that constantly interrogates its own past, examining how other scary movies scared people in order to refine and surpass them. So like almost all of the great horror films,Under the Skin exists in conversation with its forerunners. The main character’s pattern of luring lonely, horny, pasty men to a decrepit house to be consumed by some nightmare secreted from the floor evokes the plot of Clive Barker’s similar meditation on agony in the UK, Hellraiser; a late-game makeup effect recalls its even more uncompromisingly brutal sequel, Hellbound: Hellraiser II. The circular, ocular forms that dominate the movie’s abstract opening sequence recall not only the baleful gaze of the killer computer HAL 9000 in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 (a frequent point of comparison in reviews) but also the similar combination of curvilinear shapes and unnerving musical dissonance that kicks off Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (a film with which UtS shares an unarticulated but brutal meat-is-murder subtext, one that’s a lot clearer in the source novel).

Another Kubrick masterpiece, The Shining, earns a visual echo in the bird’s-eye-view shots of the characters driving the curvy roads carved through the rugged region. Its long silent passages, in which our sole window into the world of the film is the monster at its center, force us into her skin in a fashion reminiscent of Norman Bates’s clean-up and disposal in Psycho. Indeed, the ominous hums and screeching strings of Mica Levi’s score place it with Bernard Herrmann’s Psycho, John Williams’s Jaws, and the Ligeti/Penderecki/Wendy Carlos/Rachel Elkind–dominated soundtrack of The Shining at the top of the horror movie music pantheon.

The list could go on—seriously, I cut several entries for space—but it’s important to note this: None of these elements exist to be spotted, per se. They’re not overt references or homages, but rather a bedrock on which the film can be built into something new and unique. Under the Skin uses our shared vocabulary of horror tropes and techniques to create a new language, just like the disembodied syllables we hear the main character murmur over the stunning, dissociative opening sequence evolve into the words she uses to seduce and destroy.

Under the Skin is one of the best horror movies ever made, and one of the best movies I’ve ever seen, period. I make the case for it over at Decider.

This weekend I saw an okay movie called “Mad Max: Fury Road”

May 20, 2015I liked it fine. It wasn’t bad, and it was never mindless which sets it a cut above 90% of action blockbusters, but it wasn’t great. It was okay.

And it was spectacular, but the spectacle added nothing but scale. This is particularly true of the many chase sequences, which despite the well-publicized commitment to practical stuntwork had little of the white-knuckle claustrophobic about-to-break intensity of The Road Warrior. It was The Road Warrior but MORE, which in the end meant less. To be fair, The Road Warrior is flawless, a wholly original and alien vision, poetry in motion, probably the greatest action movie ever made, one of the best movies of any kind. Fury Road feels like George Miller took his masterpiece and added a bunch of unconvincing prosthetics to it, which in a sense he literally did.

To me the enthusiasm for Fury Road’s fantastical grandiosity is an echo (perhaps via influential cartoonist Brendan McCarthy, who storyboarded the film back in the day) of recent years’ fixation within the alternative/indie-comics world on Moebius and similar genre-comics artists who combine great technical ability with vivid visual imaginations; this attempt to realign the canon away from the Ware / Clowes / Doucet / Brown / Hernandez / Spiegelman / Crumb axis has been baleful for the artform in most every particular. (Simon Pegg was right.)

Miller also gave it an unambiguously happy ending, a big step back from the marvelous, singularly simultaneous gutpunch and uplift of The Road Warrior’s conclusion. A happy ending of this sort is fun, don’t get me wrong, but you can’t live off it.

Moreover, the sociopolitical praise for it, as is usually the case when people go berserk for giant pop-culture artifacts, is further evidence of the soft bigotry of low expectations. (Anita Sarkeesian was right.) You’ll be happy to hear that Mad Max: Fury Road takes a bold stand against the enslavement of women as broodmares by insane albino warlords, and that tough women with hip haircuts shoot guns in it. It’s a strange sort of progressivism that lionizes violence so long as it’s sufficiently badass and nominally egalitarian in its participants. It leaves us wishing Game of Thrones into the cornfield while demanding a Black Widow action figure in every pot.

Everyone in it was good, though, I’ll give it that as well. Tom Hardy is a god, Nicholas Hoult seems a very lively talent, Charlize Theron was rock solid. Like I said, it was fine, I enjoyed it I guess. It’s just that the existence of The Road Warrior renders it superfluous.

Movie Time: Ex Machina

May 8, 2015spoilers below

I’ve never been interested in science fiction about “what it means to be human.” That is not a question that has ever once occurred to me to ask myself, much less interested me in being asked by others. I think I’ve got a pretty good grip on it, thanks! Like, what does it mean to be human? You’re soaking in it.

Moreover, I’m so likely to err on the side of caution with regards to the issue of “killing” an artificially intelligent machine that this facet of the subgenre holds no interest for me either. I’m a vegetarian pacifist who opposes the death penalty – don’t make a machine that would feel bad about getting unplugged. Boom, done.

So that’s problem number one for Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, as far as I’m concerned.

Problem number two is that while no one likes a good Bluebeard story more than I do (with one possible exception), this one tried to have its cake and eat it too with regards to the sexy naked lady robots in the evil inventor’s death closet, and the larger issue of male privilege and misogyny the evil inventor’s death closet represented. Obviously the film intends you to find the sexy naked lady robots creepy and the evil inventor’s behavior toward them loathsome, but the parade of fabulous nude bodies that ate up the film’s third act embodied (wink) the very problems it was ostensibly intended to critique. The tell here was the fact that Ava, the main sexy naked lady robot, stood around nakedafter she’d defeated the two human men involved in the story and was free to think and act on her own. At that point, the only male calling the shots was the director.

The final problem is that despite their primacy in the narrative, the two male characters were somehow still underexplored. As a subset of points one and two, I feel like I’ve had my fill of evil sexy robot lady stories for this life, so Ava, in the end, was just not that compelling a monster to me. You know who was, though? Nathan, the genius search-engine gazillionaire and evil inventor. If you’ve ever worked for a company owned by one or two very wealthy people, you know the unique horror of realizing that another human being can pretty much literally buy and sell you, completely upending your life before going home to their own that afternoon. There were feints, and more than feints, in this direction throughout the film, but in the end he was supplanted by his much less fearsome creation.

The awful fate reserved for his opposite number, Caleb, didn’t jibe either. How could it? It’s a plot point that Caleb was selected by Nathan to participate in the Turing testing of his evil sexy robot lady precisely because he’s a good-hearted cipher – kind and caring, but with nothing connecting him to the world at large. There’s no way for the horrific events of the film to feel like they are part of an emotional economy originating in that character, since he has so little in the bank.

Yes, it looks nice, but any knucklehead can make a stylish science fiction film look nice. That’s kind of their thing.

But the music, by Portishead’s Geoff Barrow and his frequent collaborator Ben Salisbury, is overwhelming and tactile; it’s terrific. So is Oscar Isaac, so good at turning slightly-off creeps into these weird magnetic presences on film. And the dance scene? Fucking phenomenal. It’s the one part where the spectacle doesfeel like it sprang forth out of the psychic grotesquerie of this person’s brain. In that sense I guess it’s basically the “In Dreams” scene from Blue Velvet – <Morpheus voice> what if I told you this sexy, stylish psychological thriller was indebted to David Lynch? – but hey, I’ll eat it.

“Godzilla” thoughts

May 18, 2014For letting the trailers fool me, I deserve what I got. I mean, to be fair, they didn’t fool me, exactly — I’m well aware that you can make a good trailer out of pretty much any film. But the movie promised by the trailer was very much my kind of movie: well-acted horror in which the horror dwarfs and makes mock of human ambition and self-conception.

But Godzilla‘s not a horror movie, it’s a blockbuster, and by that I mean blockbuster-as-genre, with all the faults that entails: cardboard-cutout leads, buildings meaninglessly collapsing, paper-thin women characters, and the glories of the U.S. military. (Yes, in a Godzilla movie! No, mentioning Hiroshima once doesn’t cut it!) Everything that was beautiful, moving, and scary in the trailers is beautiful, moving, and scary here, but with the exception of some unexpected and laugh-out-loud funny swipes at CNN, that’s the extent of the film’s value.

The soul of those trailers, Bryan Cranston, is absolutely amazing here, displaying total commitment to the work and bringing me to the brink of tears. The problem is that he’s so much better than everyone else in the movie that (SPOILER ALERT) when he dies at the end of the second reel, any incentive to give a shit dies with him. Seriously, did they not see the problem that sticking with this twist idea would cause? He’s so incandescent in every moment he makes everyone else look like the movie was some kind of community-service sentence. Poor Ken Watanabe is given nothing to do but glower his way through some exposition, and David Strathairn’s disinterest is so palpable I half expected him to take off his mic and walk off the set at any moment. The one exception is Juliette Binoche, but she dies even before Cranston does. Perhaps Cranston’s early departure was mandated by budget or scheduling, but all I can do is critique what wound up on screen, and it’s not even a matter of a counterfactual wherein his character was the lead instead of Aaron Taylor Johnson’s nothing of a Navy bomb technician: His character was the lead for half an hour, and that’s when it was a good movie.

Godzilla has strong kaiju visual effects, certainly stronger than those of Pacific Rim; you watch this and you just think Guillermo Del Toro should be even more embarrassed for himself than he already ought to be. But it’s hardly novel in that regard: The Mist and especially Cloverfield pioneered the use of modern-day CGI to convey the horror of scale, and in those films the one-dimensional characters and hackneyed tear-jerking moments are more easily forgotten since they really are horror movies, and really do try and occasionally succeed to be frightening and bleak. For all the ranting about how Gojira will send us back to the Stone Age, this is no apocalypse: Godzilla‘s supposed to leave you cheering and hungry for the sequel. It lacks the courage of Cranston’s convictions.

Movie Time: 12 Years a Slave

December 30, 2013* A mentality by which one can see both Her and 12 Years a Slave and judge the former superior to the latter is a very foreign mentality to me. I’m grappling with that a lot tonight. There’s obviously an element of self-congratulation in preferring the horrifying historical drama about slavery to the twee portrait of an unlucky-in-love copywriter and his smartphone. And there’s an element of voyeurism, too, one only heightened by seeing the film in a packed theater full of middle-aged and elderly upper-middle-class white patrons from my preposterously segregated home of Long Island. Roxane Gay’s essay on the film for Vulture, for all it’s undergirded by presumptions about cinema I don’t share — I find brutality, spectacle, and decontextualized visual stylization, all of which she rejects at least as far as this movie is concerned, often inherently valuable in terms of conveying meaning; director Steve McQueen is proficient and profligate with all three — also makes the point that 12 Years a Slave furthers the idea that the movies about black people worth making involve their historical/political suffering at the hands of American white supremacy. All those caveats aside, I still found this film enormously compelling, as a story and as a political statement and as cinema, in ways that completely crush Her, which is routinely topping it in critics’ best-of-2013 lists. And that’s a gulf between me and other viewers that I’m thinking about a great dal.

* Crying in a crowded theater is difficult to do, for some reason. I wound up with tears streaming down my face consistently but without the usual sobbing and heaving — just a few sniffles. I’m embarrassed to say I was embarrassed.

* Stuffing your film with famous actors in bit parts is frequently a dubious proposition — remember Ted Danson in Saving Private Ryan? Yet the effect McQueen generated with that tactic here was invigorating, if menacingly so. Each time a new familiar face popped up, I found myself thinking “Oh Jesus, what’s this one gonna do?” Michael K. Williams, Paul Giamatti, Benedict Cumberbatch, Paul Dano, Sarah Paulson, Alfre Woodard, Garrett Dillahunt, Bryan Batt — each managed to be intimidating by virtue of simply being there, all famous and shit. By the time Brad Pitt showed up, an aged Golden God whose role in the narrative and his part in getting the film made in the first place combined for a sad and knowing take on the White Savior, the cameos moreover gave the film a true labor of love feeling, a “let’s put on a show” urgency.

* Though the film was written by an African American, its director and star are two black men from England, and it co-stars two more men from England as the lead character’s primary enslavers. I felt there was a unique fury brought to the material from those four outsiders’ perspectives. The crimes of an neighbor content to excuse or ignore them are often best exposed from next door. “I’m So Bored with the USA.”

* Chiwetel Ejiofor is actually better than you’ve heard. Long, lingering close-ups the first time he sings along with a spiritual, or on the day he entrusts the sympathetic white hired hand played by Pitt to write a letter to his friends back home to plead for rescue, are asked by McQueen to do nothing but allow the audience to linger in Ejiofor’s emotional and physical company as intimately as possible. He’s just remarkable.

* Lupita Nyong’o, the film’s female lead, is required to spend essentially all over her screentime in some form of extremis — the object of brutal scorn and even more brutal affection from her masters. Even during a brief respite at the brunch table of a neighbor who herself had been elevated from slave to “Mistress” thanks to her owner’s romantic inclinations, there’s a panic in the extension of her pinky finger she affects while taking tea. Her body is ultimately the tableau on which the film’s climactic act of violence is performed: the makeup effects are among the most physically upsetting I’ve ever seen, which given my predilections is saying something, but I used “tableau” because that’s what she is made to be, a canvas on which the emotions of her slaver, his wife, her fellow slave Solomon, and her own self are painted in blood. Hugely complicated, hugely upsetting. A goddamn highwire act is what it is, and she invests that character with such urgent sadness, right down to her final out-of-focus fall from the story.

* In the scenes where we see Ejiofor’s Solomon Northrup interact with his wife and kids as a free man in New York prior to his kidnapping, much of the antiquated formality of his and the other characters’ speech throughout the film, preserved from the autobiography which forms the basis of the film, necessarily falls away. Replace the horse-and-carriage with a car and the formal attire with t-shirts and jeans or whatever, and his last happy goodbye to his family (off on a business trip without him) could come from the opening of any Hollywood movie in which a good-natured family man gets fucked over by sinister forces. Which is important. Sounding like regular, everyday people by stripping away dialect, even just for a scene, goes a long way to conveying that Northrup was a regular, everyday person, until America’s nightmarish racist dystopia — a regime so repulsive and constructed on lies so preposterous we’d have a hard time accepting it as science fiction had it not actually happened in our actual history for hundreds of fucking years, were not television networks making money hand over fist by marketing its apologists as cuddly curmudgeons, were not cackling dimunitions and dismissals and denials of its horror repeated every day with the tweet of a #tcot hashtag, were its legacy not seen everywhere from voter registration laws to the lily white neighborhood i myself live in right this very second — swallowed him whole.

Movie Time: Her

December 29, 2013Her is a movie in which a nebbishy dotcom writer named Theodore Twombly dates Amy Adams, Rooney Mara, and Olivia Wilde and falls in love with a computer voiced by Scarlett Johansson. I promise you, I fucking promise you, no matter how many five-star reviews and best-of-the-year lists you come across: Whatever picture you have in your head of what such a film will feel like, that picture is correct. None of the film’s strengths — most of which, from Joaquin Phoenix’s feature-length Michael Stuhlbarg impression to some cute 120-minutes-into-the-future costume, game, and tech design, are minor; one of which, its frank and explicit treatment of sex as a component of love, is mitigated by pretty goddamn goofy voice-overacting; only a few of which, namely a small handful of its many many many conversations about falling in and out of love in the context of long-term relationships, have any heft behind them — make it worth seeking out before it winds up on Netflix Instant, or pretty much watching at all if you suspect you’d rather just rewatch Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (scripted by director Spike Jonze director Spike Jonze’s collaborator Charlie Kaufman) instead. Its biggest problem is baked right into its premise: Samantha, the computerized “her” of the title (which weirdly forefronts this computer program’s nature as a nonspecific and inscrutable female, which should set off alarm bells for you right there) is a creature of pure thought and speech, so nearly everything of note in the story is told rather than shown. With the ironic exception of a single, memorable, lengthy cut to black, the film basically never allows its visual component to do any heavy lifting. All the pretty colors, the L.A. cityscapes, the fancy simulated operating systems and video games — it’s all window(s) dressing.

Movie Time: Inside Llewyn Davis

December 28, 2013Or Introducing Bruno Delbonnel, stepping in for MIA cinematographer/genius Roger Deakins and (re)creating the grey winter awfulness of New York City so convincingly it felt less like a lighting scheme and more like a ceiling you might bump your head on. Inside Llewyn Davis, for all its subwaying and roadtripping and general peripateticism, is a claustrophobic film, a film about how having no commitments can root you to the spot just as surely as a square life. It can be seen as the third film in the Coen Brothers’ Trilogy of Calamity, with Barton Fink and A Serious Man, but here the calamity is ongoing, not a new thing that starts with a move to Hollywood or the sudden caprice of Hashem. (I suppose you could even squeeze No Country for Old Men in there too if you want, but again, no stumbling across drug money.) Llewyn Davis has been in a folk-scene funk for some time, a depression he shows no signs of exiting. Indeed, a clever bit of editing that could be taken as showing us a pivotal sequence out of order is ever so slightly recut so that we could simply be witnessing subtle variations on the same unending cycle — Sisyphus, Groundhog Day, the Möbius. Certainly the presence of a key figure at film’s end indicates Llewyn’s career will only go so far. The funny thing, the different thing, is that he’d more or less resigned himself to it by that point anyway. He’s not a delusional man, nor does he react to his plight with especially outstanding rage. He’s difficult but not impossible, cruel at times but only when driven to exhaustion by the failure of kindness to produce amicable results. He’s neither a delusional hack nor a tortured genius — he’s a talented guy who knows the limits of his talent but hopes to catch a lucky break. None is forthcoming. Joel and Ethan Coen have made much blacker movies than this one; Inside Llewyn Davis is the Coen Brothers at their greyest.

Movie Time: The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug and The Wolf of Wall Street

December 27, 2013There’s an invented scene in Peter Jackson’s second Hobbit movie (SPOILER ALERT, I GUESS) where Thorin & Company fire up the forges of the Lonely Mountain while dodging an awoken and enraged Smaug the Golden. River-like torrents of molten gold pour into a mold of (presumably) Durin, the ur-Dwarf, that’s about the size of a medium-sized office building. Smaug stares at it enraptured until the heat causes it to break form and gush golden death all over the dragon. Wealth, weaponized. Find all the metaphors for a three-film Hobbit adaptation you like in that scene, go ahead, knock yourself out. Certainly this film’s herky-jerky rhythm, and its need to surround every emotional turning point with an invented ten-minute action sequence, will give you plenty of fuel for the fire. But ultimately Smaug rises again from that lake of fire, bellows a mockery of the Dwarves’ attempt at revenge, flies up into the night sky gilded with real actual gold, shakes it off into a million droplets like a sheepdog drying off after a bath, and flies off toward Laketown to burn it to ashes while shrieking “I AM DEATH.” If I get to see something like that at the movies, Peter Jackson can melt down all the rivers of gold he wants.

Wolf was more fun than Good, and I say that as someone whose favorite Martin Scorsese movie is Casino. One of the reasons it feels a bit light in the end is that we never meet any victims of the penny-stock scams at the heart of the thing, just the scammers and their trials and tribulations. In a sense, that’s Scorsese’s approach with GoodFellas and Casino as well, but in those films the characters frequently turn on and kill each other, so you’re made to understand that the criminality has real-life consequences even if only on other criminals. You see victims; they just happen to be the victimizers as well. This, on the other hand, is just DiCaprio and Jonah Hill being really funny for three hours, with tons of naked women and quaaludes. Which I liked, don’t get me wrong, but it’s almost like Scorsese and Terence Winter (Boardwalk Empire impresario, hence a couple of notable BE castmember cameos) went out of their way to reduce the working-class schlubs DiCaprio and his merry men and women stiff to disembodied voices on phones. (EDITED TO ADD: The major exceptions are Belfort’s toddler daughter, whom his inebriated behavior terrorizes, and his second wife, whom at his nadir he physically and sexually assaults; but the rhythm of the sequence in which that occurs is such that its impact is diluted first by her turning her own rape into a way to best and humiliate her husband, then by a transference of Belfort’s threat from her to the kid. Moreover she’s portrayed as so slight a person — no Karen Hill, no Ginger Rothstein — that it’s weirdly unclear how much she’s ultimately fazed by it.) Still, as I said, really funny. A lot of it is a love letter to the grossness of Long Island, which I enjoyed, and of course the idea of just doing a one-to-one transfer of his mafia-movie style and story structure over to Wall Street is scathing and hilarious. Rob Reiner’s introductory scene had me convulsing with laughter, which I’d forgotten is a thing. Jon Bernthal erases the stink of The Walking Dead every second he’s on screen, so wholly does he commit to his ridiculous Jewish-goombah drug-dealer character. There are close-ups of Hill’s face, and an entire ‘lude-dosed fight scene, that could have come straight out of Tim & Eric’s Billion-Dollar Movie. It’s a pleasure to see Scorsese work with DiCaprio in full charismatic movie-star mode versus the aging-babyface anger he forefronted in, say, Gangs of New York and The Departed. And he’s making an argument that the best sociopaths extend their little reality bubble outward to a few trusted associates — do that and you can get away with almost literally anything. Wolves hunt best in packs.

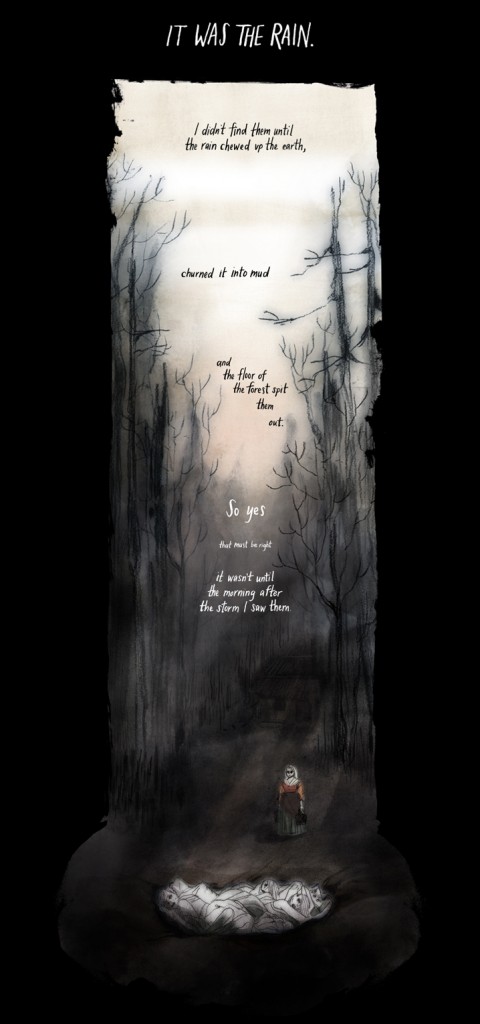

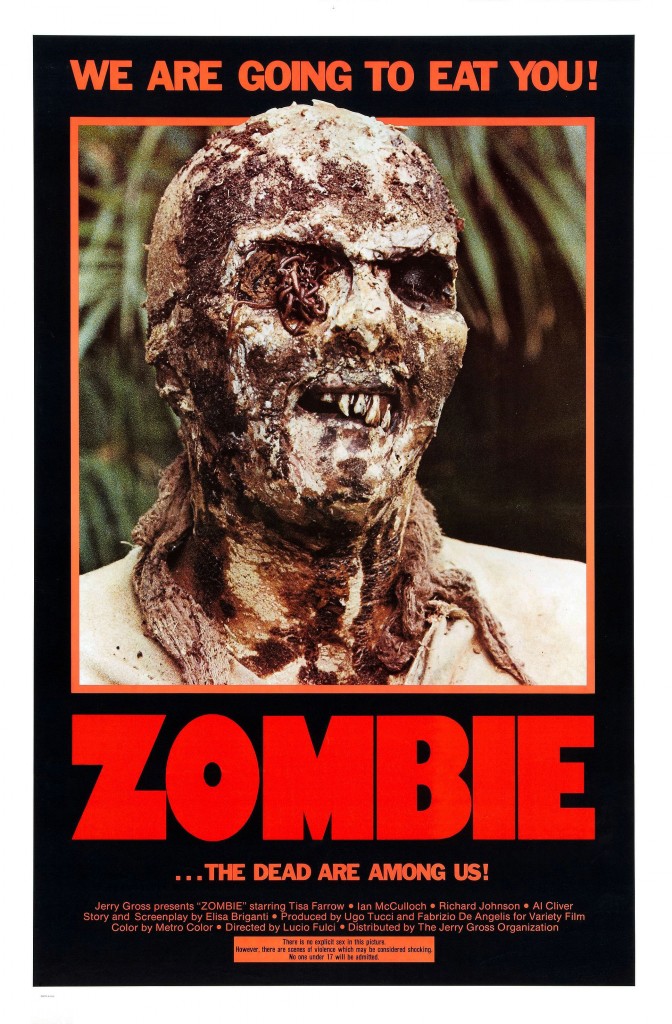

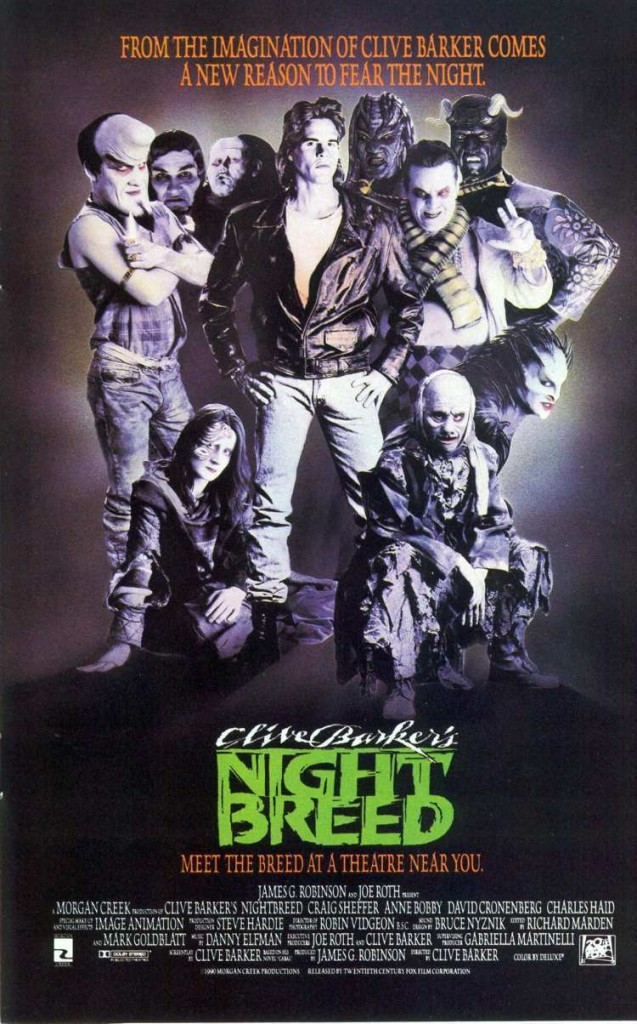

Vorpalizing: Emily Carroll, William Cardini, Lucio Fulci, Clive Barker

October 30, 2013Recently on Vorpalizer I reviewed Emily Carroll’s masterful new horror comic “Out of Skin.”

I reviewed William Cardini’s very smart fantasy one-pager “Diana in Ghost Arrow.”

I wrote about being terrified by the poster for Lucio Fulci’s Zombie/Zombi 2.

And I wrote about being terrified by Clive Barker’s Nightbreed but watching it anyway, which is how it became my first real horror movie.

Movie Time: Only God Forgives

August 7, 2013Only God Forgives is director Nicholas Winding Refn’s own Drive reaction video. The middle-aged foreign not-white cop we’re trained to think will be the villain is in fact the one who’s heroically doling out street justice, hurting only those who hurt others. He’s the Driver. The strong, silent, handsome, blond American interloper is no white savior, and he’s only even the villain accidentally, if at all. Mainly he’s a sad and ineffectual patsy, cannon fodder caught up in the larger struggle between the hero and Kristin Scott Thomas’s Tiamat figure. (Refn’s solution to making particular character troubling in that particular way is to run right at it; the last time we see her, Gosling has his hand in her fucking womb.) It’s like Refn picked us up from where we were standing at the end of Drive, moved us a couple windows over, and showed us the same thing, using our knowledge of narrative convention to show how heroism and horror are a matter of perspective.