Posts Tagged ‘david lynch’

“Twin Peaks” thoughts, Season Three, Episode Ten

July 17, 2017If all this reboot did was alternate ridiculous scenes with horrifying ones, it would still be relatively easy to get a handle on: You’d just hold your breath each time the show cut to a new location until you figured out what you were in for, and that would be that. But this series isn’t just a coin that its co-creators repeatedly flip – it’s something more multidimensional and a lot messier. Consider the scene in which Rodney Mitchum, the intimidating co-owner of the Silver Mustang Casino, gets accidentally whacked in the forehead with a remote control by his daft showgirl girlfriend Candy, who’s so intent on killing a pesky housefly that its human landing site failed to register. The emotional cacophony that follows – Candy screaming and sobbing in horror, Rodney howling in pain, his brother Bradley (Jim Belushi!) rushing in to see what’s wrong – makes you laugh. And then you cringe. And then you get genuinely worried for all involved.

This goes double for the trio’s subsequent scenes. The brothers watch a news report on Ike the Spike‘s arrest after his attempted murder of Dougie while poor Candy wonders aloud if her beau can ever love her again. Later, Mr. Jones’ sleazy coworker Anthony Sinclair (Tom Sizemore) shows up at the Silver Mustang on the orders of the Mitchums’ rival – and the evil Cooper doppelganger’s minion – Duncan Todd to pin the blame for a costly insurance loss on Dougie. He hopes that the bros will finish the job the Spike started. But Sinclair is waylaid by the increasingly unhinged-seeming showgirl, who spends an inordinate amount of time explaining the benefits of air conditioning instead of simply showing him into their office.

Both scenes dance back and forth across the boundaries between funny, creepy and skin-crawlingly uncomfortable – a shuffling boogie not unlike the one our beloved Man from Another Place used to dance across the Red Room. So, for that matter, does the whole damn show. Thanks to canny policework by Albert and Tammy, as well as supernatural interventions by the Log Lady and the spirit of Laura Palmer, lawmen like Gordon Cole and Deputy Hawk are closer than ever to cracking the mystery of Coop’s disappearance and duplication. But the creative riddle of Twin Peaks still maddeningly, gloriously unsolvable.

“Twin Peaks” thoughts, Season Three, Episode Nine

July 13, 2017Last time we visited, Twin Peaks unleashed the fires of the atom and the demons of the Black Lodge. For the follow-up, the show wants to talk about … love. Why not? If director David Lynch and co-writer/co-creator Mark Frost have proven anything in this inventive, powerful relaunch of their supernatural soap opera, it’s that they can do pretty much anything they damn well please. A show that spends minutes on end inside a nuclear explosion one week can depict lovable goofballs Deputy Andy and Lucy Brennan ordering living-room furniture the next.

“Twin Peaks” thoughts, Season Three, Episode Eight

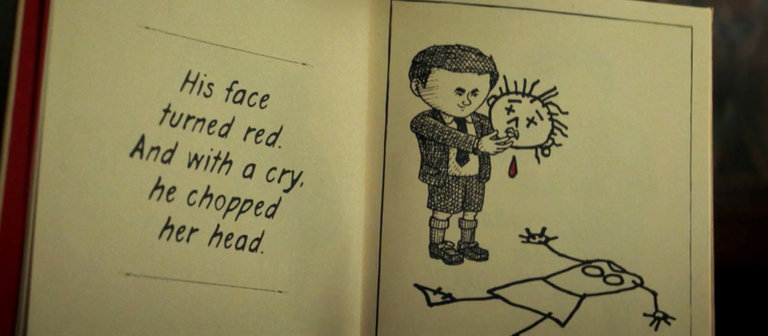

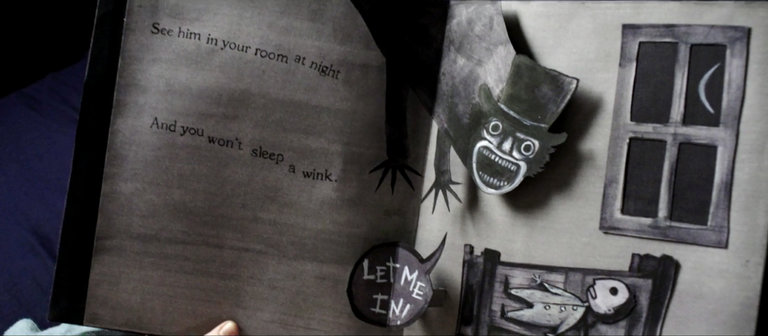

June 26, 2017What is clear is the birth of Bob’s bracing message. This disturbing, disorienting episode explicitly ties the demon’s creation to the atom bomb’s detonation, an act of man that rivals, or betters, the dark deeds of any religion’s devil. The connection is no accident. Nor is it without precedent: Ever since the original Twin Peaks introduced supernatural horror into its director’s body of work, the link between otherworldly evil and real-world brutality has been a constant. Lynch treats human cruelty like a rupture in the fabric of reality through which demons of every shape and size can enter — think Lost Highway‘s white-faced Mystery Man, Mulholland Drive‘s monstrous dumpster-dweller and gibbering old folks, Inland Empire‘s balloon-faced Phantom and, of course, the dwellers of the Black Lodge. They all feed on and perpetuate the cycle of violence that enabled their emergence.

Some experiences and emotions are so cataclysmic that our everyday imagery and vocabulary cannot possibly do them justice; monsters give shape to those feelings, the same way an aria in an opera or a song in a musical gives human passion a voice. In crafting creatures like that denim-clad monster and his dark brethren, Lynch is doing what all great horror does. He’s taking the agony and fear we already feel and, like Dr. Frankenstein in his lightning-streaked laboratory, bringing it to unholy life. The real question this episode asks, then, is no more or less than the one pilot Robert A. Lewis asked when he dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima: “My God, what have we done?”

“Twin Peaks” thoughts, Season Three, Episode Seven

June 19, 2017The third pseudo-ominous scene, and we’re gonna guess it’s the one that gets people talking, takes place in the Bang Bang Bar, a.k.a. the Road House, a.k.a. the place where we just sit around and watch a guy sweep up debris from the floor for nearly the entire duration of “Green Onions” by Booker T. and the MGs. Why? The answer that springs to mind is “why the hell not,” and hey, that’s perfectly valid. But the phone conversation that ends the scene, in which Jean-Michel Renault (no, not the long-dead sleazebag Jacques, but one of his equally gross relatives) rants and raves about the 15-year-old girls he pimped out to an unhappy client, provides a different answer. What you’ve got here is the banality of evil: A dude who can sit around twiddling his thumbs to an old R&B classic, then pick up the phone and crack jokes about statutory rape. As Jacques would say in a thick French-Canadian accent, “Bite ze bullet, baby.”

I reviewed last night’s tense and clever Twin Peaks for Rolling Stone.

“Twin Peaks” Thoughts, Season Three, Episode Six

June 14, 2017Harry Dean Stanton is 90 years old, though he’s looked so world weary for so long that he seems somehow ageless and immortal. In light of the key Twin Peaks players who’ve died before the series’ return to the air – Jack Nance, Frank Silva, Frances Bay, Don S. Davis, Warren Frost, David Bowie, and most hauntingly Miguel Ferrer and Catherine Coulson, who reprised their roles as Albert Rosenfield and the Log Lady before they passed away – we’re fortunate to have him. When his character, Carl Rodd, tells his younger companion “I’ve been smokin’ for 75 years, every fuckin’ day,” he literally laughs in the face of his own mortality. But way back when we first met him in Fire Walk With Me, set nearly 30 years ago, he intimated to a pair of FBI agents investigating a Black Lodge–related murder that he’d seen too much. “I’ve already gone places,” he said. “I just want to stay where I am.”

Making Stanton’s Carl the Virgil on our journey to this episode’s particular Hell – the hit-and-run killing of a little boy by local monster Richard Horne (Eamon Farren) – lends even more weight to the moment. It provides a contrast between the old man’s long life – achieved against the medical odds, by his own admission – and the life of the little boy, cut so horrifically short. It offers an unparalleled range of emotion, beginning with him simply sitting on a bench and enjoying the wind and light through the trees and ending with him seeing one of the worst things a person can see. And whether he’s watching the boy’s soul ascend or simply providing his mother with human connection and validation by touching her and looking into her eyes, his role is just that: to see, to bear witness. It’s not that witnesses are in short supply – plenty of bystanders observe the accident and its aftermath. But when Carl takes the next step and comforts the grieving mother, he’s the only one to bear witness – bear as in a cross.

[…]

Two crucial links to the murdered child who set the entire chain of events in motion are uncovered in an episode that forces us to confront the killing of children face-on. Laura’s face appears in the opening credits every week, but this is a way to make her presence, and her absence, hit home. Doing any less would be a cop out, a dodge, a refusal to bear witness. “What kind of world are we living in where people can behave like this—treat other people this way, without any compassion or feeling for their suffering?” asks Janey-E Jones (Naomi Watts) elsewhere in the episode. “We are living in a dark, dark age.” This show has the courage to shine a light on it.

I reviewed this week’s extremely difficult Twin Peaks for Rolling Stone. I have to say, the response I’ve gotten to my writing on the season so far, and this episode in particular, is extremely gratifying. What it’s doing means a lot to me.

“Twin Peaks” thoughts, Season Three, Episode Five

June 5, 2017The shot that hits hardest is neither comedy nor horror, but pure pleasure. It’s a close-up on the face of Becky (Amanda Seyfried!), Shelly‘s troubled daughter, staring up at the sunlit sky as she rides around in her boyfriend’s car. In this moment of literal wide-eyed wonder, the show captures the joy of being alive. But more than that, it acknowledges that this joy really couldn’t give a shit if it comes from the bump of coke you did in your good-for-nothing boyfriend’s beater. You take your happiness where you can get it, and Becky gets it riding through town with the top down and her seatbelt off, while the Paris Sisters croon “I Love How You Love Me” on the radio.

Looking back at the show’s original two seasons and the prequel film Fire Walk With Me, it’s striking how many islands of bliss and contentment its screwed-up characters carve out for themselves amid all the murder and magic and mayhem. Think about how happy Shelly and Bobby were together, despite the ever-present menace presence of her Leo. Think about Coop, delighting in everything from the camaraderie of his friends in the Bureau and the Sheriff’s Department to the simple pleasures of coffee and pie. Think about Laura Palmer herself, dancing around with her best friend Donna at a picnic just weeks before her death, her life of addiction and abuse momentarily forgotten.

And this big-hearted optimism is not just limited to Twin Peaks within Lynch’s oeuvre, for that matter. The shot of Seyfried’s Becky completely blissing out is a clear echo of the opening of Mulholland Drive, in which new cast member Naomi Watts beams so brightly about the Hollywood dreams she believes are about to come true for her. If you focus solely on the filmmaker’s use of terrifying supernatural entities, or his ironic weaponization of Americana, or his treatment of sexual violence, you could come away wrongfully believing he’s a sadist (or simply a nihilist). But moments like Becky’s car ride show that he believes happiness is possible despite our fucked-up surroundings. As good as it is to have the comedy, the tragedy and the horror of this show back on the small screen, it’s even better to have that beautiful beating heart back as well.

I reviewed tonight’s Twin Peaks for Rolling Stone. Dear god what a treat this show is.

“Twin Peaks” thoughts, Season Three, Episodes Three and Four

May 31, 2017With four hours of the The Return under our belts, it’s getting a bit easier to understand its overall approach. Is it leaning hard on all of the original’s most esoteric and terrifying material? Yes. Is it still the kind of FBI/cop show that serves as the missing link between Hill Street Blues and The X-Files? Also yes. Is it going to make time for ridiculous comedy detours just like it did 25 years ago? Again, yes. Will it serve up the love and loss of soap opera and melodrama, with the emotional volume cranked so high that it could read as parody? Once more, yes. It’s just going to do all those things slowly, parceling them out a little bit at a time over the course of multiple hours, instead of whipsawing back and forth in every single outing. The comedy of part four, for example, provides a counterbalance for the black psychedelia of part three; you need to see both, however, to strike the balance.

In other words, as suspect as this kind of description has become in TV-watching circles, the new Twin Peaks really is an 18-hour movie. If you’ve ever seen Lynch’s epic-length Inland Empire, which is three full hours of his most experimental narrative work since Eraserhead, it’s not hard to imagine the director chomping at the bit for the chance to explore obsessions over an even larger canvas. For television this gutsy and this good, he can take all the time he needs.

Teach Me How to Dougie: I reviewed episodes three and four of Twin Peaks Season Three for Rolling Stone. I think people are starting to realize that all four episodes so far have been stone fucking classics. It’s basically a miracle.

“Twin Peaks” thoughts, Season Three, Episodes One and Two

May 22, 2017It’s the first time we’ve see the Twin Peaks logo and heard the opening notes of Angelo Badalamenti’s unforgettable theme song in 25 years. When it happens, we’re looking right at the face of Laura Palmer. Director David Lynch and his co-creator and co-writer Mark Frost could have chosen pretty much any image to pair with the kick-off of the show’s almost manically anticipated return. But after a cold-open flashback that recycled footage from the original series – the sequence from the series finale in which she informs Agent Dale Cooper that she’ll see him again “in 25 years” – it’s the high-school girl whose horrific murder set the whole story in motion to whom they give the honor.

Whether in its two seasons on TV in the early 1990s or in the 1992 prequel film Fire Walk With Me, Twin Peaks has always placed Laura front and center, treating her not as a fetish object or an excuse for male characters to sleuth and mourn, but as a person deserving of our empathy and respect. All these years later, that has not changed.

Much else about the show, however, has changed. The rest of the opening credit sequence traces the progress of roaring water as it cascades down the falls, and then shows the black-and-white zig-zag floor and billowing red curtains of the Black Lodge, the nightmarish source of the story’s supernatural evil. That’s the other half of the equation for Showtime’s new Twin Peaks season, which bears the subtitle “The Return”: a plunge into magic and madness.

Words I never thought I’d type: I reviewed the season premiere of Twin Peaks for Rolling Stone.

‘Twin Peaks’: Your A to Z Guide

May 17, 2017MAJOR SPOILER ALERT

A: Angelo Badalamenti

“Where we’re from, the birds sing a pretty song and there’s always music in the air.” That music – as indispensable to to the series as Dale Cooper or donuts and coffee – is the work of Lynch’s longtime musical collaborator Angelo Badalamenti, whose suite of lush leitmotifs made the show sound like a world all its own. Twin Peaks without the composer’s sumptuous synths is like Psycho without Bernard Herrman’s screeching strings, or Jaws without John Williams’s menacing “dun-DUN-dun-DUNs.” This clip of the composer explaining how he and Lynch came up with “Laura Palmer’s Theme” shows how much heart and soul he poured into every note.B: Bob

Lynch was filming a scene for the pilot in which the late Laura Palmer’s mother sits bolt upright and screams. Then he noticed a face in the mirror behind her – the same face he himself saw when its owner, an actor turned set dresser named Frank Silva, crouched behind Laura’s bed to dodge the camera for a different shot. From this sinister coincidence was born Bob, the demonic rapist and murder from the otherworldly Black Lodge who began the series by killing Laura Palmer and ended it by possessing Agent Dale Cooper. Thanks to his malevolent presence, no show has ever been scarier.

They Are ‘Legion’: Tracking the Superhero Show’s Key Horror References

March 30, 2017

While Lynch gets the “Legion”-related headlines, another director named David seems to have left an even deeper mark. That would be David Cronenberg, who made a name for himself with a series of body-horror films that depicted the disturbing interplay between mind and matter, often with a conspiratorial backdrop of sinister secret agencies or killer corporations out to harness psychic power for their own ends.

“Legion” paints in shades of Cronenberg’s “Videodrome,” with its pulsating inanimate objects; “Shivers,” with its parasite imagery; “The Brood,” with its story of a powerful telepath under the care of a manipulative therapist (played by Oliver Reed, who may have lent both his name and his machismo to the guru figure Oliver Bird); and most especially “Scanners,” with its all-out war between rival psychic factions and a protagonist who’s telepathically tormented by the voices in his head. (“Scanners” also features a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it appearance from a very familiar-looking deep sea diver suit).

I wrote about David Cronenberg, David Lynch, and Legion’s other major horror influences for the New York Times. I have my beefs with Legion, but it’s porting its horror references into a whole different genre, as opposed to Stranger Things, which is just reheating them in the microwave and trying to pass of leftovers as a fresh-cooked dish.

The 30 Best Twin Peaks Characters

October 10, 20141. Laura Palmer

She gave the show its central mystery, and its zeitgeist-conquering catch phrase: Who killed Laura Palmer? But even though her death is literally what made the story possible, it’s her life that made it matter. Unlike the macabre MacGuffins of so many post-Peaks dead-girl mysteries, Laura was not a beautiful cipher, existing solely to inspire the male detectives investigating her murder. She was a vibrant, complicated character in her own right, the person who best embodied the small-town-secrets theme, and who paid the highest price for those secrets. Her life, and the suffering that ended it, were always foregrounded. And our glimpses of her in the series – a videotape, an audio recording, a diary entry, a visitation from Another Place – were all merely a prelude to her starring role in the prequel film Fire Walk With Me, featuring actor Sheryl Lee’s tear-down-the-sky performance of a character coming to grips with the most profound cruelty imaginable. “She’s dead, wrapped in plastic”? Yes. But she’ll live forever.

I ranked the 30 Best Twin Peaks Characters for Rolling Stone. I got so much out of doing all this writing about this show, which I love deeply and think is one of the two or three pinnacles of the entire art form of television. I hope it shows.

Living dead girl: “Dead Girl Shows,” “True Detective,” and a defense of “Twin Peaks”

May 1, 2014There’s a lot to think about in Alice Bolin’s essay “The Oldest Story: Toward a Theory of a Dead Girl Show” in the Los Angeles Review of Books. What starts as an insightful and often bleakly witty look at the strengths and weaknesses of Nic Pizzolatto’s True Detective falters when it unfairly conflates that entertaining but very deeply flawed show with David Lynch & Mark Frost’s vastly superior Twin Peaks.

“Just as for the murderers,” Bolin writes, “for the detectives in True Detective and Twin Peaks, the victim’s body is a neutral arena on which to work out male problems.” For True Detective this is, well, true. For all the show’s gestures in the direction of excoriating predation upon the less powerful by the more powerful, usually meaning upon girls by men, it’s ultimately a show that erased the very victims it purported to care for. The emotions of the male cops were our only window on their personhood and suffering.

By contrast, Twin Peaks brought us where Laura Palmer lived and forced us to keep looking at how she felt there. Indeed, Lynch made an entire prequel film for precisely that purpose (one that gives lie to the Bolin’s claim elsewhere in the essay that death prevents the Dead Girl from claiming the redemption available to the living males who investigate her death, but that’s neither here nor there). Unlike True Detective, where we as viewers are never separated from the focalizing influence of Marty, Rust, the two cops investigating them, and eventually the killer, the experiences of Laura, Maddy, and Donna were central to Twin Peaks, allowed to stand on their own, and devastating as such. Asseriting that “in Twin Peaks…the central characters are male authority figures” participates in the precise erasure the essay is decrying.

Moreover, the show worked rigorously to de-glamourize its presentation of rape and abuse. Even in the more explicit prequel film Fire Walk With Me, the sexual activities Laura initiates, though shown to be in some way sexy to her, are so because they represent crude and damaged attempts to reassert sexual agency in the face of years of horrific rape and abuse. Our glimpses of the actual rapes and assaults that take place are heartbreaking, soundtracked by screaming and sobs. The fallout for Laura, for her female classmates, for her mother — these are all chronicled unsparingly. This, and the unique and unforgivable violation represented by the identity of the killer, are what the show is about; the uncanny imagery and stunning filmmaking are intended to charge those elements, not the other way around.

Bolin also badly misreads the role of the supernatural on Twin Peaks — not just the Black Lodge and its murderous entities specifically but, I think, the nature and function of monsters in horror fiction generally. Citing the role of the demonic Bob in Laura’s murder, Bolin writes, “Externalizing the impulse to prey on young woman cleverly depicts it as both inevitable and beyond the control of men.” As evidence she cites a statement Agent Cooper makes to Sheriff Truman that the existence of supernatural evil beggars belief no more than the existence of the very human evil it helped enable. But in context, that line is intended to drive home the horror of wholly human abuse, not dismiss it. For one thing, countless male characters in Twin Peaks — Bobby, Leo, Ben Horne, the Renault brothers, Dr. Jacoby, the faraway editors of Flesh World — required no supernatural intervention whatsoever to commit their exploitative and misogynistic actions.

For another, monsters have since the dawn of time represented not just external but internal fears, our terror not just of the outside and unknown but of the impulses and excesses of mind and body we know all too well, because those minds and bodies are our own. I believe the idea that the killer bears no complicity for the killings because of the role of the supernatural isn’t even borne out by the text, but even if it were, the supernatural is not there to let male viewers off the hook in terms of their contemplation of the simultaneously universal and individualized nature of misogyny. It’s there to embody it.

The essay concludes by unfavorably comparing TD and TP to the more recent “Dead Girl show” Pretty Little Liars. It concludes:

What would seem to be Pretty Little Liars’s worst faults — its unwieldy plot, its lack of consistency, the culpability of so many characters — are actually instructive. Its creators have made a Dead Girl Show that is not about a journey instigated by a Dead Girl body toward existential knowledge, but the mess, the calamity, and the obscurity that are the consequences of misogyny.

This, of course, is an excellent description of Twin Peaks.