Posts Tagged ‘dalton’

173. And that’s tea

June 22, 2019170. Grandpa Wesley

June 19, 2019At least I assume it’s Grandpa Wesley; it’s hard to imagine Brad Wesley celebrating his matrilineal anything, even his kindly Pep-Pep. What’s for certain is that the black and white portrait on a table in his breakfast room (at least I assume it’s his breakfast room; a man of Wesley’s pretensions to feudalism almost certainly has a long oak table with high-backed chairs somewhere around that hideous house) is a portrait of his grandfather, as he announces without looking up from his breakfast when Dalton pauses in front of it.

“Looks like an important man,” Dalton says.

“He was an asshole,” Wesley replies.

This is one of my favorite stupid exchanges in the movie for a variety of reasons. Judging from the not just conciliatory but outright deferential tone Dalton adopts when he proclaims Grandfather’s importance—the “looks like” is just a turn of phrase, you can hear in his voice he’s quite certain it must be so—it’s quite possible that this was the last opportunity for peace in our time between the two most lethal men in Jasper, Missouri.

Despite enduring multiple physical assaults and murder attempts, despite seeing what Brad Wesley does to the woman in his life, this is Dalton attempting to meet Wesley where he lives, no longer just literally but emotionally as well. Surely, surely he can get this crazy old bastard to wax nostalgic about the lessons Papaw taught him, tough but fair no doubt, thunder in his voice but warmth in his heart, taught me the value of a dollar, when you forgive your enemies you create friends, you and me Dalton we’re not so very different are we?, you can hear it all play out in your mind just as clearly as Dalton could. Who would expect Wesley to grab hold of the proffered conversational life preserver long enough only to stick his ass into the middle and use it as a makeshift floating toilet before sending it bobbing on back? Not even the second greatest cooler in North America, I’ll wager.

Which is why I believe this to be one of the few occasions in which Dalton’s cooler-sense fails him.

Consider: His powers of observation, of sight and sound, of the sixth sense that can tell when trouble has walked through your door in knife-augmented boots, are unmatched at this point in the film.

Then consider: Here is the room he walked through in order to reach Brad Wesley.

What about this picture suggests to you that Brad Wesley uses the dead for decoration because he misses the time when they were alive?

169. No Country for Poptimism

June 18, 2019“Will you shut that shit off?!” Brad Wesley yells. The “you” is unidentified, although Tinker and O’Connor snap to and head in the direction of the source of the problem. The problem is the upbeat ’80s dance-pop Wesley’s abused girlfriend Denise is blasting while she exercises, which she does with Fondaesque brio despite the bruises covering her face, neck, and chest, and the ensuing shame that causes her to cover up when Dalton sees. The source of the problem is therefore Denise, who’s playing the music in the first place. “I can’t listen to that crap,” Wesley explains to Dalton as his goons force his girlfriend to turn the brisk, bright, twitterpated tune off. “It’s got no heart!” Or balls, if you prefer, since that’s the body part to which Wesley later refers when he orders a command performance from Cody at the Double Deuce. During that performance, Denise is prompted to get on stage and strip, which she does with talent and enthusiasm. Then it’s Dalton’s turn to complain about Denise’s homage to Euterpe and Terpsichore. He refers to her as a dog who should be kept on a leash.

To the characteristically awful Wesley and the uncharacteristically mean-spirited Dalton, there’s nothing more aggravating than a woman enjoying art on anything approaching her own terms, even if it’s while working out to shake off the beating she received the night before, even if it’s taking off her clothes in front of a room full of baying strangers not for her own sake or her own financial health but to aid her abuser in his weird power trip. Music that lacks roots-rock authenticity, dancing that sexualizes the woman dancing with insufficient deference to the concerns of the man watching—these grave injustices must be stopped.

If Brad Wesley and James Dalton weren’t locked in a life-and-death struggle over a bar, they’d write one hell of a Black Mirror episode.

168. At the center of it all

June 17, 2019The speech in which Brad Wesley touts his accomplishments as a captain of industry to Dalton over breakfast and a Bloody Mary, revealing all of those accomplishments to involve the local establishment of downscale retail chains, is memorable for the obvious reason that this film’s chief antagonist says the sentence “Christ, JC Penney is comin’ here because of me!”

But that is not the only reason it stands out. Watch how cinematographer Dean Cundey (Jurassic Park, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Back to the Future, The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China, The Fog, Escape from New York) established Brad Wesley’s centrality to his own narrative by making him the center of the shot in which he spells out that narrative.

As Wesley rattles off his life story—coming up the hard way on the streets of Chicago, arriving in this nothing of a town after Korea, building it up into an empire of Fotomats, amassing both popular acclaim and a fortune in cash—the camera follows Dalton as he walks around Wesley at the perimeter of the round room in which he sits eating at a round table. It focuses on Dalton at the beginning of the journey, shifts to Wesley near the midpoint, and pulls back to Dalton at journey’s end. Their relative positions in the frame shift as well: Wesley starts at the left and winds up at the right, while Dalton does the opposite.

What is the purpose of this perspectival pas de deux, this theater in the roundhouse? To visually convey Wesley’s narcissism and his delusions of grandeur (which in the world of the film can be passed off for actual grandeur in a pinch). To emphasize the wary, hunter/hunted relationship between Dalton and Wesley, with their shifting focus and placement in the frame making it difficult to ascertain who is the predator and who is the prey. To show off the fancy house the locations team secured for the production. To give Ben Gazzara a platform on which to declaim without so much as having to stop eating his scrambled eggs. It is a truly accomplished shot, in the sense that it accomplishes a great deal. Is it any surprise that, depending on how one counts the opening and closing credits rolling over live band performances, it is at or near the exact center of the film?

166. Details

June 15, 2019As a visual text, Road House is a chest of wonders. Look at this shot from early on in the film, on the night when Dalton first visits the Double Deuce. There he is at his familiar post, in his familiar shapeless beige jacket. There’s Pat McGurn and The Bartender Who Must Not Be Named behind him, conferring about whatever a sister-son and a working stiff who both happen to have the same job at the same place might confer about. (“So what’s it like working with Exene after the divorce? And this Mortensen kid she’s with, is he cool? Because he seems cool.”)

To the left is a power drinker, passed out on the bar; from this we can infer that Pat, ever conscious of the needs of his uncles liquor distributorship, refuses to cut off even the most obviously inebriated patrons, and most likely pressures the Nameless One into doing the same. Given the behavior of the comparatively sober customers, what does he have to lose, really.

To the right is a detail I’m just now noticing: the dry spongy exposed foam of the bar’s padding, chipped and peeled and torn away by the half-hearted vandalism of the drunk and the fixated. Back in the “everything is padded” days of restaurateurship, such artifacts of idle destructiveness were visible everywhere. I haven’t sat on an upholstered seat at an upholstered table in many a long year, but I can feel the satisfaction of ripping away a chip of covering and pulling at the porous brown stuffing underneath like my hands are doing it right now instead of typing this sentence. For all that Road House is rightfully dinged about its lack of realism, even as regards bar furniture specifically (the price of replacement tables alone from the fight about to ensue would put a normal establishment out of business), that’s some real shit.

And to the right of that? Why, that familiar fellow is none other than Brad Welsey’s own Tinker. Has he come to chat with fellow Wesleyans Pat and Morgan about the art of the goon over a few drinks when they have a moment to spare during their busy evenings of stealing from the cash register and erupting into violence over the slightest provocation? Is he additional muscle to make sure Mr. Wesley’s liquor flows without impediment? Is he simply a fan of the Jeff Healey Band? At another time during this sequence he’s seen chatting up some lovely lady; is the Double Deuce his fern bar, his Regal Beagle? Is this Tinker Tinder?

I’m reminded here of the extensive making-of documentaries included in the Lord of the Rings extended edition sets. I don’t remember the exact wording offered by the heads of the various costume and design and set departments regarding their lunatic attention to detail. I do remember the gist of it, though: They would produce intricate designs for the insides of garments and scabbards or for swords that would only be seen from a distance or for rooms no one would even enter or what have you not because the audience would see them, which they knew they wouldn’t. They did so because they were creating a world for the entire production to inhabit, not just the viewer. A cast or crew member who spent a few seconds admiring the embroidery of their breeches would be that much closer to convincingly conveying the reality of a world of orcs and elves and hobbits and magic rings. Look at the shot above, really look at it, and tell me if he war between the world’s most famous bouncers and the maniac mall devleoper who keeps their bar in Jim Beam seems as much of a stretch as it did before.

163. Bad goons

June 12, 2019Call me old fashioned, but I believe that when the insane 7-Eleven franchisee who pays you to beat people up sends you to pick someone up and bring that person to him for a conversation, and that person gets up to go with you, you shouldn’t flinch like he just pulled out a gun. Yet that is certainly the reaction of Tinker and the Bleeder when, after Tinker says “Mr. Wesley wants to see you. Let’s go,” Dalton…gets up to go see Mr. Wesley.

This is the one time in the entire film when Tinker and O’Connor do a job that does not immediately go amiss, but their loser mindset has conditioned them to expect a beating no matter what. If they’d offered Dalton a handshake and he reached out to shake hands in response they’d burst out in flopsweat while pulling out a bowie knife. If they’d asked Dalton out on a date and he showed up to the date they’d shoot at him through the window of the diner.

You could chalk this up to Dalton’s martial prowess, with some justification. I mean, you can see what happened to them the last time they tangled with the cooler the moment you look at them. But I think that when it comes right down to it, Brad Wesley does not have a good eye for talent. Does he not say so himself when, following the defeat of Tinker and O’Connor and Pat McGurn in their attempt to restore the sister-son to his job at the Double Deuce, he ruefully acknowledges he should have sent Jimmy, one of two or three goons in his employ who’s actually good at his job? (Karpis very effectively trashed Red Webster’s auto shop in his sole observable mission, and while Ketchum lost in humiliating fashion in the parking-lot brawl, he winds up running over a car dealership with a monster truck and murdering Sam Elliott.)

Small wonder the purpose of this go-see is to try and hire Dalton away from the Double Deuce. Wesley can read the bruises and gashes all over his employees just as well as Dalton can, though admittedly in O’Connor’s case he’s responsible for at least as much damage himself.

But that ship has sailed. By hiring Dalton as his first act in the creation of the new Double Deuce, and also by establishing a bridge to Wade Garrett via Dalton, Frank Tilghman once again proves himself the town’s true visionary. He is a man who builds power; Wesley, who parasitically feeds off the town just as he coasts on the hard work of the founders of JC Penney and Fotomat, can only buy it piecemeal. In the time it would take him to accrue enough Tinkers and O’Connors to take down the likes of Dalton, the fight would already be lost.

162. Kiss

June 11, 2019Dalton and Elizabeth’s first kiss is as much a kiss of acceptance as of romance. Their awkward, oddly hostile first date concluded, they have returned to the parking lot of the Double Deuce so Dalton can pick up his car to drive it back to Emmett’s ranch. They find its tires flattened and its window impaled with an uprooted stop sign. Doc, quick-witted as ever, quips “Your fan club?”

“They are devoted,” Dalton chuckles.

“You live some kind of life, Dalton.” This is delivered as a summation of the night’s conversation. Whether he’s ever been bested, ever been put down, ever wondered why, ever thought about the morality of accepting money to beat people, ever considered whether or not his nice guy act works—in seeing that ruined car Elizabeth appears to realize that these questions are moot. Dalton is a man willing to martyr himself so the kinds of people who’ll fuck up some guy’s car just for doing his job don’t get to do it to other people more vulnerable, less capable of fighting back. She heeds the stop sign, in other words, and lays her doubts to rest, for now anyway.

Dalton doesn’t know this yet. He sees his ruined car and sees, well, a ruined car. Now that part of his life has been displayed to the Doc, along with his battered body. It isn’t a pretty picture. (Not even his perfect physique is necessarily that impressive to someone who’s stapled it shut.)

“Too ugly for you,” he says. In classic Road House fashion this is a statement, not a question. He’s offering an answer of his own.

Then comes the happy surprise, the eucatastrophe, from the mouth of the Doc: “I didn’t say that.”

The kiss that follows (after some awkward seatbelt fumbling) is soft, nearly chaste, one sustained contact with the lips and then a release. It’s a benediction. So much is said with this one kiss that when the time comes for Dalton and Elizabeth to make love, neither feels the need to kiss again until the act has been consummated. To the extent that a kiss is the physical expression of intimacy, what can be more intimate than “I understand”?

159. The future’s so bright, I gotta wear shades

June 8, 2019When Tinker and the Bleeder are sent to collect Dalton for an audience with Brad Wesley, they do so wearing bigass aviator sunglasses. It’s sunny out, I get that. But both these men have been badly beaten recently: Tinker by the bouncers at the Double Deuce, O’Connor by Dalton at the Double Deuce, and O’Connor again by his own boss, Brad Wesley, in the driveway of the very house to which he’s delivered his quarry. You can see a bandage sticking out from under the shades, in fact. Sadly he’s not the sort to wear concealer to cover up the bruise above his lip, but he’s trying his best to look healthy, together, and intimidating in front of two men who literally beat him unconscious on consecutive days. I get why: Abusers see weakness, and they hate it, and they exploit it, and it reminds them of the anger they felt when they inflicted the damage that caused the weakness and it makes them angry all over again, and god forbid word of what’s going on gets out.

I don’t mean to take this in such a heavy direction, but consider who else is in this scene.

That’s Denise, charming horny vivacious together Denise. The night before, she hit on Dalton with no regard for subtlety whatsoever: She saw what she wanted and went for it. From a personal emotional perspective it’s one of the most impressive things anyone does with anyone else in this farkakte movie, which frequently bears the same relationship to actual human interaction that Lego minifigures have to actual human hands. But it takes place in front of Jimmy, Brad’s bastard son [citation needed], who drags her strugging out of the bar, through the parking lot, and into a nearby vehicle. Jimmy gives the high sign to Ketchum and his squad of men who’ve ordered the Rooty Tooty Fresh ‘n’ Fruity at IHOP after church on Sunday move in to attempt to assassinate the man she just hit on by kicking his skull with a knife. Denise, it appears safe to assume, is brought back to Brad Wesley’s house, where he and perhaps Jimmy beat the living fucking shit out of her.

I’ll give Dalton this much regarding his conduct toward Denise, a definite character lowlight in many other regards: Seeing what Brad Wesley did to her seems to factor into his last-straw decision to react to Wesley’s overtures with open hostility. I say “seems” because he’s most visibly pissed off when Wesley brings up the fact that Dalton killed a man who’d discovered he was fucking his wife, and that could be enough. I’m just giving him the benefit of the doubt is all.

Anyway, you’ll notice no sunglasses have been afforded to Denise. No warning that Brad would be receiving company, either. She’s in the middle of an aerobics routine with music blasting when Tinker and O’Connor roll in with Dalton in tow, because getting beaten bloody by your boyfriend is no justification for an off day.

In conclusion, O’Connor and Tinker get off easy, and O’Connor gets murdered by the end of the movie. Throw some sunglasses on his corpse.

158. Salute

June 7, 2019Some men see a bouncer who gets paid a low-mid six-figure yearly salary to beat up the agents of a local racketeer with a Fotomat in a dirt-parking-lot dive-bar shithole in Jasper Missouri conclude a date during which he got read to filth to his face multiple times by a woman he met in a trauma ward when she stapled his latest stab wound shut without anesthesia before showing up to their date while he was in the middle of a street fight by giving her a chaste kiss on the lips and then saying goodbye with a weird little half-assed naval salute while holding the stop sign his enemies jammed through his car window after slashing all his tires and say, why; I watch Road House and say, why not?

157. “Hey, pretty girl. Time to wake up.”

June 6, 2019156. “Now you will see me one more time if you do good. You will see me two more times if you do bad. Goodnight.”

June 5, 2019154. Tonight’s rent

June 3, 2019Road House is all over the map when it comes to crusty weird old guy solidarity. It is undoubtedly true that a Frank Tilghman/Pete Strodenmire/Red Webster/Emmett alliance tandem-murders Brad Wesley to end his reign of terror and free Jasper forever. But this requires the sacrifice of their comrade in grizzledness Wade Garrett, as well as a great deal of groundwork laid by young Dalton, who murdered five people and incapacitated a sixth with a stuffed polar bear so that the old timers could infiltrate the Wesley compound. Moreover, it is precisely the lack of solidarity shown by Brad Wesley, himself a weird old man, that necessitated this revolution of the geriatrics in the first place. And where does this leave Big T and the red-hatted gentlemen who are among the Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri? Excluded, alienated, and atomized, that’s where.

Dalton, perforce, addresses a similar breach as his deeply weird bad date with Dr. Elizabeth Clay winds to a close. “Pretty soon I’m gonna have to start charging that bum rent!” growls the counterman at the diner, presumably the owner judging from his literal rent-seeking behavior, regarding the exhausted and/or drunk gentleman Dalton kept from collapsing onto the floor a few seconds earlier. Stepping in to do so once again, Dalton reaches into the pocket of his ostentatiously loose-fitting white trousers and throws some money onto the counter in the owner’s direction. “Tonight’s rent,” he deadpans, leaving the old bastard to scowl and the other old bastard to sleep in peace.

Here we see the fraying seam between Dalton’s priggish elitism and his salt-of-the-earth affectations more clearly than ever before. He rights for the rights of everydrunk, provided he’s not being paid to keep such men out of his place of work. (Recall if you will the power drinkers and the trustees of modern chemistry.) He’s a liberator armed with the money he earns in the course of oppression. He’ll take care of tonight but tomorrow you’re on your own. Maybe Doc is right. Maybe he isn’t a nice guy after all.

153. “You ain’t no nice guy!”

June 2, 2019Caught completely off guard by an opponent he didn’t see coming (not yet anyway, rimshot), Dalton straight-up gives up on his date with the Doc. I’m serious, man, he just takes his balls and goes home. He drops his smile, fidgets, looks out the window, takes a final drag of his cigarette, and acts like he’s just had the completely unrelated idea that it’s time to take her home. “I keep talking, you’re gonna go off thinking I’m a nice guy.” He’s putting his pack of Marlboros into his jacket pocket, he’s smiling and raising his eyebrows and doing little head nods, haha, he’s back in business baby!

Done with looking away from this man, Elizabeth reclaims his gaze, seizes control of it. Her voice a bedroom-fireplace crackle, her smile spreading like an inkblot, she looks him dead in the eyes and says “I know you’re not a nice guy.”

Pain don’t hurt, or so we’ve been told. From this we can conclude, can we not, that Dalton is a sub, or at the very least (and given what we see of his later behavior this proves out) a switch. It follows that the moment Dr. Elizabeth Clay smiles at him while calling him a piece of shit is the moment Dalton falls in love with Dr. Elizabeth Clay.

It will all go very smoothly from there, I’m quite sure.

Take it away, Larry Underwood and friend.

“Sure,” she said, cringing back and starting to cry. “Why not? Big star. Fuck

and run. I thought you were a nice guy. You ain’t no nice guy.” Several tears

ran down her cheeks, dropped from her jaw, and plopped onto her upper chest.

Fascinated, he watched one of them roll down the slope of her right breast and

perch on the nipple. It had a magnifying effect. He could see pores, and one

black hair sprouting from the inner edge of the aureole. Jesus Christ, I’m going

crazy, he thought wonderingly.“I have to go,” he said. His white cloth jacket was on the foot of the bed. He

picked it up and slung it over his shoulder.“You ain’t no nice guy!” she cried at him as he went into the living room. “I

only went with you because I thought you were a nice guy!”The sight of the living room made him feel like groaning. On the couch where

he dimly remembered being gobbled were at least two dozen copies of “Baby, Can

You Dig Your Man?” Three more were on the turntable of the dusty portable

stereo. On the far wall was a huge poster of Ryan O’Neal and Ali McGraw. Being

gobbled means never having to say you’re sorry, ha-ha. Jesus, I am going crazy.She stood in the bedroom doorway, still crying, pathetic in her half-slip. He

could see a nick on one of her shins where she had cut herself shaving.“Listen, give me a call,” she said. “I ain’t mad.”

He should have said, “Sure,” and that would have been the end of it. Instead

he heard his mouth utter a crazy laugh and then, “Your kippers are burning.”She screamed at him and started across the room, only to trip over a throw-

pillow on the floor and go sprawling. One of her arms knocked over a half-empty

bottle of milk and rocked the empty bottle of Scotch standing next to it. Holy

God, Larry thought, were we mixing those?He got out quickly and pounded down the stairs. As he went down the last six

steps to the front door, he heard her in the upstairs hall, yelling down: “You

ain’t no nice guy! You ain’t no—”He slammed the door behind him and misty, humid warmth washed over him,

carrying the aroma of spring trees and automobile exhaust. It was perfume after

the smell of frying grease and stale cigarette smoke. He still had the crazy

cigarette, now burned down to the filter, and he threw it into the gutter and

took a deep breath of the fresh air. Wonderful to be out of that craziness.

Return with us now to those wonderful days of normalcy as weAbove and behind him a window went up with a rattling bang and he knew what

was coming next.“I hope you rot!” she screamed down at him. The Compleat Bronx Fishwife. “I

hope you fall in front of some fuckin subway train! You ain’t no singer! You’re

shitty in bed! You louse! Pound this up your ass! Take this to ya mother, you

louse! “The milk bottle came zipping down from her second-floor bedroom window. Larry

ducked. It went off in the gutter like a bomb, spraying the street with glass

fragments. The Scotch bottle came next, twirling end over end, to crash nearly

at his feet. Whatever else she was, her aim was terrifying. He broke into a run,

holding one arm over his head. This madness was never going to end.From behind him came a final long braying cry, triumphant with juicy Bronx

intonation: “KISS MY ASS, YOU CHEAP BAAASTARD!” Then he was around the corner

and on the expressway overpass, leaning over, laughing with a shaky intensity

that was nearly hysteria, watching the cars pass below.“Couldn’t you have handled that better?” he said, totally unaware he was

speaking out loud. “Oh man, you coulda done better than that. That was a bad

scene. Crap on that, man.” He realized he was speaking aloud, and another burst

of laughter escaped him. He suddenly felt a dizzy, spinning nausea in his

stomach and squeezed his eyes tightly closed. A memory circuit in the Department

of Masochism clicked open and he heard Wayne Stukey saying, There’s something in

you that’s like biting on tinfoil.He had treated the girl like an old whore on the morning after the frathouse

gangbang.You ain’t no nice guy.

I am. I am.

But when the people at the big party had protested his decision to cut them

off, he had threatened to call the police, and he had meant it. Hadn’t he? Yes.

Yes, he had. Most of them were strangers, true, he could care if they crapped on

a landmine, but four or five of the protestors had gone back to the old days.And Wayne Stukey, that bastard, standing in the doorway with his arms folded

like a hanging judge on the big day.Sal Doria going out, saying: If this is what it does to guys like you, Larry, I wish you were still playing sessions.

He opened his eyes and turned away from the overpass, looking for a cab. Oh

sure. The outraged friend bit. If Sal was such a big friend, what was he doing

there sucking off him in the first place? I was stupid and nobody likes to see a

stupid guy wise up. That’s the real story.You ain’t no nice guy.

“I am a nice guy,” he said sulkily. “And whose business is it, anyway?”

A cab was coming and Larry flagged it. It seemed to hesitate a moment before

pulling up to the curb, and Larry remembered the blood on his forehead. He

opened the back door and climbed in before the guy could change his mind.“Manhattan. The Chemical Bank Building on Park,” he said.

The cab pulled out into traffic. “You got a cut on your forehead, guy,” the

cabbie said.“A girl threw a spatula at me,” Larry said absently.

The cabbie offered him a strange false smile of commiseration and drove on,

leaving Larry to settle back and try to imagine how he was going to explain his

night out to his mother.

152. It’s a dirty job

June 1, 2019Let the negging commence. With his typical poetic elision and equally typical lack of awareness as to how he might come across to a normal person, Dalton has given the Doc his best guess as to why he’s been so successful as a bouncer and cooler: “The ones who go looking for trouble are not much of a problem as someone who’s ready for them. I suspect it’s always been that way.” But here comes trouble he’s not ready for at all: the kind of withering, barely-worth-the-effort condescension and contempt he’s shown to lesser men throughout the film, aimed right back at him.

As soon as he’s done epigrammatically gassing himself up and righting a listing derelict sitting nearby—acting on a signal from Elizabeth, who nods in the man’s direction to tip him off—he turns back and exchanges a smile with his date. How can she resist the charms of a knight errant?

“Somebody has to do it,” she says, smiling broadly, broadly enough that he doesn’t notice that she’s saying his job is quite stupid.

“Somebody’s gotta pay somebody to do it,” he replies in another typical rhetorical ploy, the poet/workin’ man two-step. Here’s my eloquent summary of my raison d’être, here’s me rollin’ up my sleeves, scratchin’ my balls, and takin’ out the trash.

Taking her eyes off of him, looking down at the table or into her own lap, smiling almost ruefully, she says “Might as well be you.” She says it like Larry Underwood’s mother sighing about the trouble her son the famous musician has gotten himself into out there in The Stand. All the things you could have done with your life, James Dalton, and this is what you choose. Not a question, a statement. This is what you are. Okay. If that’s the way it has to be.

Her smile becomes a ghost and then vanishes altogether. Dalton’s follows as if it has no choice in the matter at all. Not in this matter.

Dalton has no comeback here. Larry would hem and haw and mewl a bit before finally giving in; Dalton, a trained fighter, knows when he’s been beaten. The disapproval, the disappointment, is worse than the trouble itself. It is the trouble. Trouble he was not ready for at all.

150. Ready for trouble

May 30, 2019“The ones who go looking for trouble are not much of a problem as someone who’s ready for them,” Dalton tells Dr. Elizabeth Clay, immediately before reaching over to effortlessly keep an exhausted old drunk from passing out and falling right off his chair at the counter. Here we see the flipside to Dalton’s obliviousness to his true nature as discussed in the previous entry. The reason Dalton fails to consider the ways in which he has gone looking for trouble throughout his life is because, as a matter of day-to-day life, he is more actively aware of and invested in preventing trouble from finding others. Making ready for trouble rather than looking for it is what occupies his mind. I’d call this self-flattery or even narcissism if it weren’t for the fact that, well, he kept that old man from falling off his chair, didn’t he?

149. Which Side Are You On

May 29, 2019I could write an essay a day about Road House for a full calendar year and never come close to summarizing Dalton as neatly as this: He tells the woman he will come to love “The ones who go looking for trouble are not much of a problem as someone who’s ready for them” as if it’s never occurred to him that a man who beats up other men for a living might be the former instead of the latter.

148. The ones who go looking for trouble

May 28, 2019Dalton is always better than his opponents, pretty much. He’s never been put down, not really. This much we learn from leading questions by Dr. Elizabeth Clay during her date with Dalton at Bonnie’s Grill. One can assume we’re joining the questioning already in progress given the uncomfortably long period of silence prior to the first one, during which she takes a sip of her coffee and he takes a drag of his cigarette. That’s not the awkward pause of two people just beginning a conversation and waiting for someone to voluntarily select the starting line. That’s the awkward pause that has onlookers going “yikes.”

But these are the facts as Dalton and the Doc have established them. Dalton is superior. Dalton is undefeated. Only one question remains, and the Doc, and displaying the diagnostic acumen that’s made her the finest student of Hippocrates in the Jasper, Missouri metropolitan area, asks it: “How do you explain that?”

“The ones who go looking for trouble are not much of a problem as someone who’s ready for them,” he replies. [Sic.] “I suspect it’s always been that way.”

While Dalton garbles his response the intent is clear enough. Troublemakers are no match for people who’ve spent some time, or in his case their entire professional lives, preparing for them. Never underestimating your opponent, expecting the unexpected, you know the drill.

But this isn’t just an explanation, it’s a demonstration.

Consider Elizabeth’s questions pertaining to Dalton’s win-loss record. She’s already been disabused of the notion that his vast array of injuries indicates he loses his fights during his visit to the ER, but how, exactly? With his zen-clear response that nobody ever wins a fight. He doesn’t just “nuh-uh!!” her, he recalibrates her view of combat.

Now look at what he does here. “Are you always better than they are?” “Pretty much.” “Never been put down?” “No, not really.” Look how expertly he dodges, rather than parries, her thrusts. He’s not going to assert outright that he’s always the better man; yeah, pretty much, sure, I guess. He’s not going to state unequivocally that he’s never been put down; no, not really, I mean at the very least he gets up at the the end while the other guys don’t, pretty much, it’s complicated but yeah, no.

Despite the third degree delivered in a raspy and intimate bedroom voice, and despite the tense and awkward atmosphere (watch this space), Dalton does not wilt before her merciless gaze. He’s going to yield just enough ground each time to deny her the me vs. you framework she’s reaching for. He’s going to involve her in making her own determinations on each question in such a way that does not require her to ever explicitly contradict him. She can cling to the “pretty much” and the “not really” if she’s determined to do so…which, due to the presence of the “pretty much” and the “not really” in the first place, she’s less likely to do.

The ones who go looking for trouble are not much of a problem as someone who’s ready for them.

If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig.

136. (There’s A) Fire in the Night

May 26, 2019“Hi.”

“Hi.”

“So, you lookin’ for somebody?”

“You.”

You’ve just read the conversation Dalton has with Elizabeth when he spots her and her dress outside the Double Deuce. She’s leaning back against a post, a pose she’ll have occasion to revisit later in the course of their relationship. He’s just finished whipping someone’s ass, which, same. They have an easy and unmistakably sexual intimacy here that the film spends the following scene, depicting their coffee date at a local greasy spoon, blows to smithereens. Yet it’s really only upon repeated viewings that the Doc’s repeated and rather open and vicious skepticism regarding Dalton’s career and character alike becomes apparent. Rather it reads like a tiger and tigress sizing each other up, deciding whether when and where to fuck, knowing they have within them the power to annihilate each other but choosing to do something else to each other instead, something hot to the touch and sweet to the skin. I credit Kelly Lynch and Patrick Swayze with much of that, since there’s hardly a person either character meets at any point in the movie you can’t imagine jumping right into the sack with them with the slightest provocation, and that’s no less true here. But mostly I credit the band Alabama and their song “(There’s A) Fire in the Night.”

Despite spending the better part of my adult life among music critics and music nerds and being both myself, I’ve never heard Alabama so much as mentioned outside country circles. Whatever it is that’s allowed my cohort to deify Johnny Cash and Dolly Parton and Willie Nelson, make a crossover star out of Kacey Musgraves, turn Garth Brooks’s “Friends in Low Places” into an NYC karaoke staple, place the country affectations of Tom Petty and Stevie Nicks front and center in their respective late-period critical celebrations, and allow Lil Nas X & Billy Ray Cyrus’s “Old Town Road” to happen has never touched the biggest band in the history of the genre.

Listening to this song it is very, very difficult to understand why. Occupying the overlap position in the Bob Seger’s “Night Moves” / Bruce Springsteen’s “I’m on Fire” / The Smiths’ “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out” Venn diagram you didn’t know existed, its minimal, dry guitars and water-on-the-snare-drums ’80s beat tell help singer Randy Owen tell his tale of one great night with one helluva woman. It’s not breaking any kind of ground (except perhaps the tight and expansive-sounding vocal harmonies during the chorus) and that’s the point. It’s guiding you, expertly, through familiar territory—bedrooms you’ve slept in and the people you’ve slept next to in them and your memories of both. Who wouldn’t want to warm their hands by that fire again?

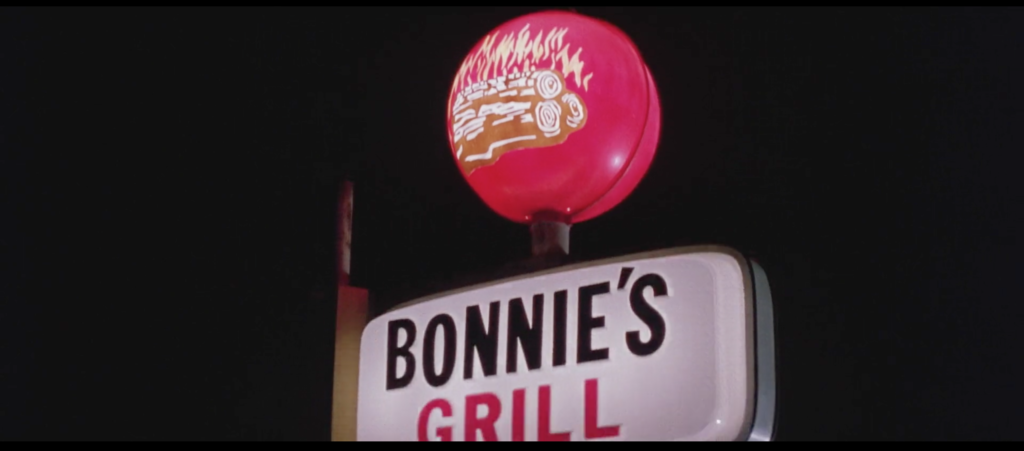

The quick cut that follows Elizabeth’s explanatory “Me” leads us directly to a night sky, blank of stars moon and cloud. The camera descends onto a red orb emblazoned with a roaring fire. It descends further still, revealing the light-up signage of a diner. It’s an echo of the opening shot, which tells you right there that what follows is, in some as yet undefined way, momentous.

But it’s that rhythmic, percussive, low guitar line that sells the mood. When you hear that, and you see the night sky, and you take in the comfortingly ersatz glow of the lights, and you identify the kind of establishment we’re visiting, your mind quite naturally imagines a couple in the moments between when they realize they’re going home together and when they get up to do so. That tension and reserve is all in Jeff Cook’s insistent, somehow twitchy guitar. You pick up on instantly, you contextualize it effortlessly, you know what it’s about before Randy Owen’s singing comes in and proves you right.

Things don’t go great on the date itself, as we’ll see, though again not as bad as they appear at first glance, as we’ll also see. So for me, the music is the message here, and the message speaks true. Not for nothing is our first glimpse of this scene a fire in the night. One is being kindled whether the kindling and the tinder know it yet or not.

144. The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as I best could, but when he ventured upon insult I vowed revenge.

May 24, 2019Here’s Ketchum, the clear second to Jimmy in the hierarchy of Brad Wesley’s goons and his successor upon his death in much the same way that the unspecified entity Gothmog assumed control of the assault on Minas Tirith following the death of the Witch-king of Angmar, getting dragged out of the Double Deuce on his ass into the dirt parking lot outside. Bumpty bumpty bump, right down the front steps, squealing and mewling over his injured ankle all the way. In a matter of seconds, Dalton thwarted his assassination attempt, caught his leg in midair, ruthlessly twisted it, yelled “You’re too stupid to have a good time!” right in his face, toppled him to the ground, and dragged his ass, literally, into the dirt, also literally. Such is the indignity of this forced exit that, get this, his extended free leg is actually what opens the right-hand door (facing the building) while Dalton shoulders open the left. He is forced to facilitate his own humiliating defeat.

Now in addition to being the most anonymous of Wesley’s core goons, Ketchum is also the least sympathetic. My guess is that the two phenomena are interrelated. Can’t feel sympathy for a guy you can’t remember!

But recall that in the world of the story, Ketchum is a thought leader, a ring general , a man to whom the Tinkers and Bleeders and sister-sons of the world are supposed to look for guidance. Both Tinker and O’Connor—Tinker! and O’Connor!—fare better in their fight against Dalton than Ketchum does in his. Dalton beats Ketchum like a mule. To keep up the ring-general jargon, bahgawd ref, stop the damn match.

Later in the film, Ketchum murders Wade Garrett.

“They’re not my brothers,” Jon snapped. “They hate me because I’m better than they are.”

“No. They hate you because you act like you’re better than they are. They look at you and see a castle-bred bastard who thinks he’s a lordling.” The armorer leaned close. “You’re no lordling. Remember that. You’re a Snow, not a Stark. You’re a bastard and a bully.”

“A bully?” Jon almost choked on the word. The accusation was so unjust it took his breath away. “They were the ones who came after me. Four of them.”

“Four that you’ve humiliated in the yard. Four who are probably afraid of you. I’ve watched you fight. It’s not training with you. Put a good edge on your sword, and they’d be dead meat; you know it, I know it, they know it. You leave them nothing. You shame them. Does that make you proud?”

Jon hesitated. He did feel proud when he won. Why shouldn’t he? But the armorer was taking that away too, making it sound as if he were doing something wrong. “They’re all older than me,” he said defensively.

“Older and bigger and stronger, that’s the truth. I’ll wager your master-at-arms taught you how to fight bigger men at Winterfell, though. Who was he, some old knight?”

“Ser Rodrik Cassel,” Jon said warily. There was a trap here. He felt it closing around him.

Donal Noye leaned forward, into Jon’s face. “Now think on this, boy. None of these others have ever had a master-at-arms until Ser Alliser. Their fathers were farmers and wagonmen and poachers, smiths and miners and oars on a trading galley. What they know of fighting they learned between decks, in the alleys of Oldtown and Lannisport, in wayside brothels and taverns on the kingsroad. They may have clacked a few sticks together before they came here, but I promise you, not one in twenty was ever rich enough to own a real sword.” His look was grim. “So how do you like the taste of your victories now, Lord Snow?”

“Don’t call me that!” Jon said sharply, but the force had gone out of his anger. Suddenly he felt ashamed and guilty.“I never…I didn’t think…”

“Best you start thinking,” Noye warned him. “That, or sleep with a dagger by your bed. Now go.”

—George R.R. Martin, A Game of Thrones