Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

Comics Time: Mouse Guard: Fall 1152

March 26, 2008Mouse Guard: Fall 1152

David Petersen, writer/artist

Villard Books, March 2008

200 pages

$17.95

David Petersen is a prodigiously talented illustrator, no question. When it comes to being a writer, he may not know art, but he knows what he likes. In its somber, Tolkienesque way, this tale of swordplay and strife amid warring factions of medieval mice warriors is just as much a product of the “art of enthusiasm” school of genre mash-up as Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim or Brubaker, Fraction, and Aja’s The Immortal Iron Fist, or even Neil Marshall’s Doomsday. Without a hint of irony it clearly exists to repackage Petersen’s favorite tropes–Joseph Campbell’s hero with a thousand faces, Watership Down‘s red in tooth and claw fuzzy-rodent society, Tolkien’s faux-archaiac prose, Ralph Bakshi’s rotoscoped villains–into a whole that satisfies his own obsessions, all in the hopes that it will satisfy others’ as well.

Mission accomplished on that score, at least for this reviewer, at least for the most part. Listen, I’m sure there are more hardcore fantasy devotees out there who would tear it to shreds for its likeable but stock characters and storylines (three guesses as to whether the black mouse called Midnight is the Guard’s secret traitor) and the clunkiness of the prose (“There I found the record of legend being fact”). Comics readers might object to pacing that frequently gets ahead of itself (introductory text pieces that kick off each chapter deliver vital information skipped by the comic itself; the climax of the story arrives too suddenly). You can probably tell from those flaws whether or not this thing is your cup of meat; there are probably many of you for whom it isn’t. I for one wish the book displayed even a modicum of self-awareness, let alone humor, about itself; I can’t imagine Petersen thinks anything other than he’s making one for the ages, and that loss of perspective hurts him at critical moments, from shading his characters to recognizing the failure of the ending.

But never once did I feel like my intelligence was insulted, a prerequisite for any action-adventure comic that many fail to meet. Nor did I feel like I was “reading” a series of pin-ups or illustrations instead of a comic. For all his pure chops–the lush, textural colors, the evocatively shaky line, the note-perfect cute-savage mouse designs–Petersen does indeed cartoon in these pages. The sound effect for a snake’s hiss weaves sinuously through the foliage. A sudden cut to a goggles-wearing mouse elicits a guffaw. Astute use of photorealism gives predatory snakes and crabs an otherworldly air. Even the format–the pages are square!–speaks to Petersen’s confidence in his vision. It’s not quite fully realized, indeed for anyone other than Petersen it probably couldn’t be, but as comics’ answer to Harry Potter it entertained me enough to tune in next time.

Comics Time: Across the Universe: The DC Universe Stories of Alan Moore

March 24, 2008Across the Universe: The DC Universe Stories of Alan Moore

Alan Moore, writer

Dave Gibbons, Klaus Janson, Jim Baikie, Kevin O’Neill, Paris Cullins, Rick Veitch, Al Williamson, Joe Orlando, Bill Willingham, George Freeman, artists

DC Comics, 2003

208 pages

$19.95

Though it’s now out of print, having been supplanted by a collection that also includes the longer stories Batman: The Killing Joke and Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?, this particular anthology of mainline-DC stories by Alan Moore is the superior book, and not just because of the absence of the irksome reproduction errors that plagued the two aforementioned stories in the later edition. Without those two tales–both of them swinging-for-the-fences “last word” efforts about their respective milieus, grim’n’gritty Batman and Silver Age Superman–overshadowing the proceedings, we’re able to better compare in apples-to-apples fashion the short stories that remain, and better appreciate their pleasurable successes–and almost as pleasurable failures.

Moore’s superhero work dealt with the same problems as any superhero story–devising wild science-fiction settings, creating threats believable enough to overwhelm the audience’s knowledge that nothing bad is really gonna happen to our hero, deriving resonance from each character’s time-honored tropes. The best I can do to describe what he did differently from his contemporaries is to say that he solved these problems by attacking them from a completely different direction than any other writer at the time.

For example, in not one but two separate “Superman vs. parasitical plant life” stories–the Swamp Thing crossover “The Jungle Line” and the now-classic be-careful-what-you-wish-for tale “For the Man Who Has Everything”–Moore makes the all but invulnerable Superman eminently vulnerable, physically and emotionally, by tying him back to his roots in the apocalyptic extermination of Krypton and its inhabitants. Rather than simply throw another alien powerhouse or supergenius at the guy as most writers would do, Moore plays off the “Last Son” aspect of the character to create a threat that’s primarily emotional rather than physical or mental–blazing a path that’s still followed by the character’s most successful interpreters to this day.

Many of his other novel approaches stem from the classical science-fiction notion of a “literature of ideas,” as opposed to the superhero science-fiction norm of humanoid aliens in crazy clothes with laser guns. These stories’ strength is one of raw concept: How would a Green Lantern power ring operate for a being with no concept of light or sight? How do you conquer beings who operate on a time frame so slow that it would take them years to even notice your presence? How do you teach the birds and the bees to a species with no females? Why limit the aliens we encounter to more or less humanoid forms when they could be sentient planets or sentient smallpox viruses? It’s a litany of the kind of idea that’d blow the minds of anyone whose idea of science fiction began on Tattooine and ended on Krypton.

The art in the collection firmly roots it to the time of its origin. To a superhero reader raised on the high-gloss, digitally colored, border-busting, photoref’d slugfests of today, it all must look hopelessly primitive; even the artists who still have some name-recognition juice today, like Dave “Watchmen” Gibbons and Klaus Janson, come across as quaintly classicist and nostalgically sloppy respectively. (God only knows what a Greg Land fan would make of the Lovecraftian avant-garde demons in Kevin O’Neill’s creepy Green Lantern story!) But this too plays to Moore’s strengths as a writer in this period by harkening back to a simpler time before the writer grew so fixated on form and referentiality, instead preferring simple superhero morality plays of idea and emotion.

Not everything works, not by a long shot. Stories involving street-level heroes Green Arrow & Black Canary and Vigilante are distinguished primarily by less-than-enthralling narrative conceits, the former likening a night in the big city to an athletic event for no clear reason and the latter interspersing Vigilante’s team-up with a comically clichéd party girl (“I’ve got forty kilos of good Colombian weed stashed up there!”) with excerpts from the creepily loving letter of the pedophile they’re chasing to his intended victim. A Batman story from the perspective of an obscure, insane villain who thinks he’s perfectly sane has its limitations revealed by the two decades’ worth of such stories that followed. All the standard pitfalls of ’80s superhero comics can be found at one point or another: multiracial vest-wearing street gangs, howlingly unrealistic dialect, incongruously forcing clunky sci-fi ideas into conversational speech (“Why are you still staring out of the window? The underlights of Aunt Allura’s paragondola vanished five units ago.”).

But those good stories—the Superman, Green Lantern, and Vega ones mostly—are really awfully good. Best of all they make it seem like telling a good story was Moore’s only goal. Maybe that’s why I enjoy this book as much as almost anything I’ve read by the bard of Northampton: With no Victoriana to riff on and no snake gods to worship, the guy can spin a heckuva yarn.

Comics Time: Hellboy Junior

March 21, 2008Hellboy Junior

Mike Mignola, Bill Wray, writers

Mignola, Hilary Barta, Dave Cooper, Stephen Destefano, Pat McEown, Kevin Nowlan, artists

Dark Horse Comics, January 2004

120 pages

$14.95

Originally written on June 23, 2004 for publication by The Comics Journal

The post-movie-version influx of new readers to a tie-in title has, at least since the first Batman film, been something of a chimera for mainstream comics publishers. This is most likely because nearly everyone on Earth is already aware that (say) Spider-Man comics exist, and have made up their minds long ago whether or not they are actually going to buy such things, regardless of whether or not they agree with Gene Shalit’s assessment that the character’s celluloid incarnation is “a non-stop thrill ride” or what have you. Seen in that light, Mike Mignola’s much-lauded but relatively obscure Hellboy actually has more in common with Ghost World than The Hulk, and the bona-fide sales boom for Hellboy graphic novels after the film’s critical and commercial success bears this out.

One can only wonder, then, what Joe & Jane Q. Non-Fanboy would think were they to wander into their local Android’s Dungeon (or, more likely, Borders) in search of further adventures of the sardonic, demonic paranormal investigator, only to pick up a copy of Hellboy Junior instead. Sure, Ron Perlman is a great comic actor, even under six inches of prosthetics. But could even his wittiest mid-battle bon mot prepare the unwary reader for a comic in which a young Hellboy pays for mail-order hallucinogenic mushrooms with gold teeth pulled out of the mouth of an emetophagic Idi Amin, who is later rewarded by Satan with sex for all eternity with a septuagenarian nun?

Such is the sense of humor on display in this completely out-of-left-field anthology, released this spring and comprised of comics originally published in the late ’90s. Primarily an extended riff on Mignola’s character by gonzo humor cartoonist and Ren & Stimpy collaborator Bill Wray, Hellboy Junior largely eschews the former’s eerie, deadpan comedy for something much closer to Angry Youth Comix. Pustules abound, as do vomit, interspecies sex, and dismemberment. It may sound overly broad and scattershot, but it’s done with an offensive brio that makes it difficult not to go along, and laugh while you’re at it. Well, laugh, or exclaim “Holy shit.” This is, after all, a Muppet Babies version of a beloved hero, and here he is involved in stories that end with Bob Hope emceeing at the crucifixion of Hitler.

The Hellboy Junior stories themselves are a mixed bag. “The Devil Don’t Smoke,” drawn by Mignola himself, contains the kind of non-sequitur humor that made Mignola’s The Amazing Screw-On Head such a treat (there’s a one-panel cameo appearance by an imperious skeleton with a nail through his head, you know what I mean?), and as such is far removed from the sicko gags of the rest of the book. Artist Dave Cooper makes “Hellboy Jr’s Magical Mushroom Trip” every bit as visually rich as you’d expect, though the real star of the show may well be Cooper’s luminous covers and smart lettering, which depict the various stages of H.J.’s reverie with perfectly evocative clarity. But the two Hellboy tales drawn by Wray run on well past the point of diminishing returns–maggots, violence, abusing Hitler, yes, we get it.

Indeed, the funniest, and not coincidentally the most offensive, moments come not in the Hellboy material, but in Wray’s incongruous parodies of old Harvey comics and other storybook & cartoon icons. Baby Huey, for example, is re-imagined by Wray and artist Stephen DeStefano as Huge Retarded Duck, an enormous diaper-clad imbecile who graphically disembowels three redneck ducklings during their attempted rape of his mother, only to impregnate her himself. Folks, that’s comedy. Throw in an Acme-style ad for the Spear of Destiny (“I couldn’t have killed Christ without it!” raves Gaius Cassius, Roman Centurion) and sharp, sleazy art turns by Hilary Barta and Pat McEown, and you’ve got a package that’ll amuse the deviant 15-year-old in all of us. Let’s just hope it doesn’t single-handedly derail the semi-horned one’s marketing mojo.

Comics Time: Battlestack Galacti-crap

March 19, 2008Battlestack Galacti-crap

Brian Chippendale, writer/artist

self-published, January 2005

28 pages

I forget how much it cost and can’t find a realistic price anywhere online

Buy it from Target, believe it or not

The other day I mentioned that Micrographica‘s casual quality did not mesh well with its presentation as a perfectbound graphic novella. Battlestack Galacti-crap, on the other hand, is exactly what it should be–a crazy little minicomic with a bright green-and-pink silkscreend cover and photocopied pages that look like they can barely contain the throwaway wildness they document.

The product of Fort Thunder alum/Lightning Bolt drummer/Ninja and Maggots author/Björk collaborator Brian Chippendale, its “story” is kind of like The Wire for three-year-olds: A group of gaudily costumed creatures called Gang Gloom has the bright idea to sell cheap cupcakes down on Stack Street, a move that the members of rival outfit Teamy Weamy don’t take kindly to. The resulting rumble, “of course,” ends up with all the participants stacked on top of each other in tangled-up tower of crazy creatures–apparently that’s how “any interaction on Stack Street always ends.”

Something about this minicomic tapped into a long-forgotten vein of surreal action-humor in my psyche. When I was a kid I seem to remember being fascinated by the idea of people/things being so stuck together they couldn’t move, yet not treating this like a crisis and simply chit-chatting with each other like it’s a minor inconvenience. (This seems like a Jim Henson kinda idea–was it from a Muppet movie?) Needless to say it’s a perfect fit with Chippendale’s method of choice for cartooning, which is to fill up as much of the page with visual information as he can, and the scenes of dozens of helmet and mask-wearing characters mashed together are appropriately sloppy and exuberant. But many of the characters get a chance to shine on either end of the action in the ersatz pin-up pages that kick off and conclude the story. In both cases the art provides the visual punch for Chippendale’s goofy sense of humor: The solo shots of the characters proposing the cupcake-selling idea grant an absurd sense of grandeur to the silly proceedings, while the suggestion by one guy at the bottom of the titular “battlestack” that another’s back injury might be cured by one of the recipes in his handy copy of Healing with Whole Foods reaches a Pythonesque level of comic incongruity. And then there’s that lovely page where someone yells “EVERYBODY OFF!” and the stack collapses in a dynamically lovely waterfall of falling bodies. Top to bottom, this minicomic is a miniature model of form fitting function.

Comics Time: Kill Your Boyfriend

March 17, 2008Kill Your Boyfriend

Grant Morrison, writer

Philip Bond, artist

DC/Vertigo, 1995

62 pages

$5.95

Buy it used for, like, $40 from Amazon.com

There was a time, circa the moment in high school when I nicknamed my then-girlfriend’s breasts Mickey and Mallory, when I would have thought this astonishingly earnest encomium to the liberation of smart high-schoolers via sex, drugs, violence, and arty notions of personal identity was the coolest motherfucking book I’d ever read. There have also been times, like the moment I realized how incredibly stupid it was to give that same girlfriend a copy of Sin City bearing the inscription “I’ll be your Marv if you’ll be my Goldie” for her birthday and not expect her to be disturbed by my comparing her to a dead prostitute, that a book like this would have earned sneers of derision and/or waves of nausea from me.

At this particular moment, however, I’m at a Goldilocks-like level of just-right comfort with this comic. Goddess only knows if Grant Morrison intended lines like “The only way to stop being bored is to do something interesting or criminal. These days it comes to the same thing” with a straight face, but viewed from the remove of 14 years Kill Your Boyfriend strike me less as po-faced Warren Ellis-style pop-violent hipsterism and more of an embrace-cum-pastiche of its most ridiculous aspects, an exercise in depicting the mindset of a bored kid who’s too cool for school and too smart for his own good than a demonstration of being embarrassingly trapped in that mindset. Little flourishes throughout the comic point in that self-aware direction: The presence of genuinely transgressive elements, like unwitting incest, that are left on the page to be troubling and never get absolved via the I’m-okay-you’re-okay treatment (a la Alan Moore’s Smax); the seeming acknowledgment via a group of all-talk-no-action art students that this comic itself is all talk and no action; the use of direct address by the teenage-girl protagonist, with word balloons disarmingly replacing narrative captions, to highlight the unreality of the narrative and the comparative cipher nature of the glamorous-criminal boyfriend figure; the fact that the ballyhooed killing spree really only includes two murders (Natural Born Killers or Bonnie and Clyde this isn’t). Even some of the stuff that I think can be read more straightforwardly, like the Girl’s proclamation of her first sexual encounter as “brilliant,” is fine with me, since so was mine, and fuck the bluenose prudery that drums otherwise into everyone’s head.

Of course there’s plenty here that’s kind of a mess. The run-on declamations of everyone’s awesomeness are way too on-the-nose. The Girl’s square original boyfriend is a mess of contradictory character traits–fantasy-geek prurience jars bizarrely with condescending asceticism, and the notion that any teenage guy would turn down actual sex in favor of jerking off is ludicrous on its face. The ending, with its “whoa look out your normal-looking neighbor might be a killcrazy former sex maniac who took E and liked it so watch out you dead-behind-the-eyes wage slave” message was surely just as played out when it was written in 1994 as it is now. And the Vertigo-mandated occlusion of any actual explicitness when it comes to sex is as cringe-inducing as always, given how far they’ll take the violence and how much they pride themselves on being “mature.” But nothing can be too terrible when it’s drawn by Philip Bond, whose Britpop cartooniness couldn’t be more perfect for this material. Overall it’s not a comic I see myself returning to very often, but as a warts-and-all time capsule of what it’s like to be one of Morrison’s archetypal “smart 14-year-olds,” you could do worse.

Comics Time: Micrographica

March 14, 2008Micrographica

Renee French, writer/artist

Top Shelf, May 2007

208 pages

$10

I’m rarely as baffled by a comic as I am by this one. Originally drawn in one-centimeter-square panels and published online, it’s the “story” of three tiny rodents who at varying times find a ball of shit, a corpse, a grub, a bigger rodent, and a sandwich. It’s a weird mixture of South Park potty humor and French’s trademark body-horror, the uncomfortable intimacy of which is somehow made even more disturbing by the scale of the drawings even though you’d think the gag-cartoon nature of the material itself would mitigate against it. Believe me, it doesn’t.

I think French is a very, very good cartoonist, and it’s a testament to her abilities that the procrustean parameters she imposed on her drawings for this project didn’t prevent her from exploiting the vulnerable, exposed physicality of her characters as well as she always does, bulbously distended noses, eczema-ridden nipples and all. The sticking point is the intentionally, admittedly slapdash nature of the story. On the one hand, it’s always refreshing to me to see a cartoonist present a comic that defies the usual niceties of story structure or readily graspable “meaning.” On the other, I’m not sure that kind of braindump necessarily warrants presentation as a stand-alone graphic novella that costs ten bucks. As a minicomic or a story in an anthology, it would be easier to swallow somehow, though I understand that the one-panel-per-page set-up probably precludes publication in such venues.

Comics Time: Justice League: The New Frontier Special

March 12, 2008Justice League: The New Frontier Special

Darwyn Cooke, writer

Cooke, David Bullock, J. Bone, artists

DC Comics, March 2008

48 pages

$4.99

Here it is at DC’s website but I don’t think you can buy it there

I’ve long been a skeptic with regards to writer-artist Darwyn Cooke’s nostalgia-tinged approach to superheroes in titles like The Spirit and DC: The New Frontier (the antecedent to this one-shot and the basis of the animated feature to which its release is tied). What’s interesting about Cooke’s take on the topic is that it dodges many of the usual pitfalls of “they don’t make ’em like they used to”-ism by acknowledging that these are not products of a more innocent era–the era they come from, like all eras, was actually pretty fucked up. Rather, he slips up by insisting that the classic superheroes themselves are viable moral exemplars. To me this is very weird and a little icky. I don’t think we can really derive any kind of meaningful ethical guidelines from the career of Green Lantern–I mostly just think characters who dress up in cool costumes and use awesome powers to fight crime and tyranny and killer aliens can make for some fun stories with some powerful emotional beats. Now, the specific flaw of the New Frontier project of depciting the Silver Age DC icons as active in the actual time period that spawned them is that it takes Cooke’s problematic approach to superheroes and applies it to the Kennedy era itself, even though, given the actual historical record, viewing JFK in this hagiographical manner is almost as dubious as treating Batman that way. At any rate, as symbols of a brave new world of muscular Camelot progressivism, I’m not sure masked vigilantes make a whole lot of sense.

But to its great credit, JL:TNFS largely eschews the more heavy-handed philosophical elements of its predecessor, instead focusing on telling a ripping mid-’50s period yarn about Batman and Superman fighting, Dark Knight Returns-style. Frankly I’ll never get tired of Batman handing Superman’s ass to him with Kryptonite weapons, and seeing him do so via the effortlessly dynamic, feet-kicked-up-on-the-desk casual, retro-cool art of Cooke is all the better. Moreover, the short-story length mitigates against Cooke’s tendency toward bloat–there’s no room to cram in any multi-page paeans to Adam Strange! Instead, the special is rounded out by a pair of shorter, humor-oriented stories illustrated by Cooke collaborators Bullock (a Robin/Kid Flash team-up involving an unholy union between drag-racing delinquents and Communist saboteurs, which is a pretty fabulous idea) and Bone (a raid on a Playboy club by Wonder Woman and Black Canary which ends with Gloria Steinem in bunny regalia winking at the viewer; I’m still trying to figure out what was going on with this one other than Cooke riffing on the fact that Wondy was on the cover of the first issue of Ms. and that women look good in fishnet stockings).

I suppose what I would like New Frontier to be is a Watchmen-esque application of superheroes to a specific political and temporal milieu, whereby we can sit back and watch how things play out for these icons in a setting a lot more constrained than their usual anything-goes shared universe without the material telling us how to feel about what happens. In other words I don’t want the reverence to go any deeper than Cooke’s gorgeous throwback art. That’s not really what we’re getting here, but it’s brief enough and cool enough that I can pretend.

Comics Time: Scott Pilgrim Vol. 4: Scott Pilgrim Gets It Together

March 10, 2008Scott Pilgrim Vol. 4: Scott Pilgrim Gets It Together

Bryan Lee O’Malley, writer/artist

Oni Press, October 2007

216 pages

$11.95

You see a lot of criticism of the movie Juno centering on its stylized hipster-nerd banter. I haven’t seen the film, but I understand it involves the phrases “home skillet” and “honest to blog,” and that does indeed sound unfortunate. I would guess that someone out there could make similar hay out of the Scott Pilgrim series. Everyone is very “on” and clever and buoyant and witty and catty, a little like a stylized version of what you’d like to think you and your friends constantly sound like: “Scott, if your life had a face I would punch it. I would punch your life in the face.” Surely there’s people who’d just as soon light the book on fire as read lines like that.

I’m not one of those people. I find the Scott Pilgrim world so winning, so immersive. Part of it is that dialogue, which makes you feel like you’re entering another, more entertaining world. Part of it is the books’ Nintendo-realism, and the sense-memory of playing video games conjured up every time Scott wins experience points or levels up. Part of it is the tremendously charming art, which gets more stylized and self-assured with each new volume. While at times I wish O’Malley’s characters were a little easier to tell apart, I actually got the hang of it pretty quickly this time because each of them has some little stylistic filigree–bangs or freckles or a ponytail or a beard or somesuch–that economically sets them apart.

And part of it is the characters. They’re admittedly not the deepest or most complex bunch, but I want fun things to happen to them. I want all of Scott’s cute female friends to make out with each other (even though the trendy-lesbian thing is a little easy–I mean, so am I). I want his roommate Wallace to party with his pants off. I want his snotty bandmates to dole out put-downs like Judge Judy and Dr. Phil. Now, do I want Scott really to get it together? I’m not so sure. I’m kind of enjoying him falling bass-ackwards into everything, like the Dude from The Big Lebowski or Kramer from Seinfeld. Still, I really enjoyed the story of his estranged rock-star ex-girlfriend Envy from Vol. 3, and while this installment’s saga of whether he and Ramona will finally say “I love you” isn’t quite as satisfying, it does at least begin to grapple not just with the emotional aspect of post-initial-infatuation relationships, but also with the sexual aspects, which had kind of been elided until now. I like reading Scott Pilgrim comics.

Comics Time: Blankets

March 7, 2008Blankets

Top Shelf, July 2003

Craig Thompson, writer/artist

592 pages

$29.95

Originally written on March 8, 2004 for publication by The Comics Journal

It’s safe to describe Blankets as the year’s most talked-about, most hyped, most divisive graphic novel. It’s also safe to describe it as one of the year’s best. The victim of an emperor’s-new-clothes backlash that in at least some cases had as much to do with the book’s publisher or its author’s previous work or the p.r. campaign surrounding it as with the book itself, Blankets is a marvelously drawn bildungsroman with a heart as big as the Midwestern plains in which it takes place. For that, it has been pilloried, and I wish I could understand why. Actually, scratch that–no, I don’t. If loving this rapturously illustrated and warmly told story of ecstatic pain is wrong, well, you know the rest.

Blankets is the more-or-less straight autobiography that author Craig Thompson’s debut novel, Goodbye, Chunky Rice, hinted at. Indeed, elements of Chunky Rice put in cameo appearances throughout its successor’s 592 pages, hinting at a rich underlying emotional universe in much the same way that The Lord of the Rings provided deeper and sadder echoes of material first found in The Hobbit. It’s a book about long-distance relationships–one with a girl, one with God; how they burn impossibly bright and yet can be extinguished with a phone call (in the former case) or a footnote (in the latter). Refusing to coast on mere audience recognition, Thompson’s art both mines and mimes the riot of emotion such relationships engender, employing sweepingly expressive brushwork–each page seems to swirl like a snowdrift–and a vast–perhaps “dizzying” is a better word–array of formally experimental devices. And yet the art steers clear of the facile: Everyone notices the “blankets” of lush white snow, but a careful scan through the book reveals an almost obsessive use of powerful blacks, the unspoken yang to the wintry yin. Thompson’s narration is believably unreliable, at times appearing to believe every word of its descriptions of sexual or spiritual perfection, at other times imbuing the delivery with that unmistakable you-can’t-go-home-again regret, at all times trusting the reader to make the distinction. What we’re left with is a book about rejecting Christianity that, miraculously, judges not; a book about adolescence that recognizes that term as one describing an age, not a level of complexity, or more specifically a lack thereof. In love and in loss, what happens to our teenaged hearts matters. So does Blankets.

Comics Time: Death Note Vol. 2

March 5, 2008Death Note Vol. 2

Tsugumi Ohba, writer

Takeshi Obata, artist

Pookie Rolf, translator/adapter

Viz, November 2005

200 pages

$7.95

First of all, look at that price point–talk about bang for the buck! No wonder these things are so popular. Second of all I found this volume to be an improvement over its predecessor in virtually every respect. The art is more interesting and individualized in its depiction of the characters: I loved the big bag-rimmed eyes, wiggly bare toes, and thumb-biting neurosis of L the wunderkind investigator, and man oh man I could look at the clothes and hair Obata delivered for the ill-fated Naomi Misora all day. But of course we won’t be seeing much of her anymore, and that’s part and parcel of the improvement in terms of the tension of the cat-and-mouse suspense aspects seen in this issue: We see just how far Light will go to preserve his anonymity by killing off very likeable, very innocent characters, and by having that happen this early in the game, the creators show us that no one is safe and that they’ll be throwing curveballs. I still get a little tired of the constant narration of everyone’s thoughts and deductions–I long for the quiet cogitation of the characters from The Wire, which I’m experiencing for the first time more or less simultaneously to Death Note and which displays a lot more faith in the audience to follow what’s going on–but I’ll admit that it’s an effective way of showing off how byzantine the schemes and counter-schemes get from moment to moment. It’s enjoyable pulp fiction.

Comics Time: Blar

March 3, 2008Blar

Drew Weing, writer/artist

Little House Comics, 2005

20 pages

$3.25

This minicomic about an adorable barbarian killing machine and his gag-strip adventures reminds me of Roger Langridge’s Fred the Clown stuff in three particulars: 1) The bigfoot-style cartooning is absolutely impeccable (I actually prefer this to Langridge–it’s warmer and humbler, if that makes sense); 2) the humor stems primarily from a human shortcoming (in this case stupidity, in Langridge’s case usually a combination of stupidity and venality) being expressed through comic business; 3) the comic business isn’t funny. Seriously, I’d love to see this character in a far more straightforward action-adventure mode, one that’s as ridiculous as this is and just as chock full of crazy enemies (The Berserker Hordes of Nazroth! The Dread Wizard-King! Mecha-King Gilgator!) but stripped of the shallow pratfall-based punchlines.

Did I mention the cartooning, though? Christ. Actually the book’s most entertaining aspects stem from the art more than the business–the house-sized sword in the final strip is a laugh-out-loud riff on the Berserk school of big-ass-sword-wielding, and that die-cut blood splatter on the front cover is witty and eye-catching (that cover scan doesn’t do it justice at all), and I love that Blar’s arm is almost always extended perpendicular to his body, with his sword perpendicular to his arm. The jokes could be that good too!

Comics Time: The Chunky Gnars: A Chocolate Gun Tribute

February 29, 2008The Chunky Gnars: A Chocolate Gun Tribute

Chris Cornwell, writer/artist

PictureBox Inc., October 2007

16 pages

$3.00

Like Paul Pope’s cover version of the first issue of Jack Kirby’s OMAC from his issue of Solo and Josh Simmons’s unauthorized Batman-as-psychopath minicomic Batman, Chris Cornwell’s Chunky Gnars mines the fertile vein of another creator’s work, in this case Frank Santoro & Ben Jones’s wondrous drug-teen-rock-action opus Cold Heat. I think these kinds of call-and-response comics can really tease out what works and doesn’t work in the original and be an extremely enlightening exercise for the responder.

In this case, Cornwell doesn’t quite hit the heights that the originators do, but to be fair that doesn’t seem like his intent–his goal is playing up the mixed-genre nature of Cold Heat for humorous effect, like having a rock-star-slash-assassin and an evil senator piloting a giant robot minotaur. Some of those moments are very funny, in fact, if a little catchphrasey–“I don’t start killin’…TILL I’M DONE ROCKIN’!!” shots the hipster assassin when the senator tries to get him to skip the encore and start the massacre. Better still is Cornwell’s funny-because-it’s-true depiction of the senator’s absurd, obliviously prurient fixation on the supposed evil of popular culture: Beads of sweat running down his bald head (which has suddenly been isolated against an oozing abstract background), he kicks off a test run of his latest speech with the immortal opener “We have become a nation that worships the rectum,” before his assistant unceremoniously cuts this reverie off.

While the whole thing doesn’t exactly cohere nor rise to the level of its inspiration, it does contain some gaze-worthy art that is at alternating times reminiscent of Santoro, Brian Chippendale, and in the second of its four title panels Beto Hernandez. Mostly it exists as a testament to how fired up Cold Heat has people, which is valuable in and of itself.

Comics Time: Aline and the Others

February 27, 2008Aline and the Others

Guy Delisle, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, November 2006

72 pages

$9.95

On the one hand this book is an absolutely magnificent display of bravura cartooning–understated, energetic, loose as a goose, full of the joy of imagemaking. In a fashion reminiscent of Bill Plympton’s animated shorts, Delisle creates miniature portraits of various, mostly unpleasant women in wordless-strip form. The uniform layouts–tight grids of 15 tiny square panels per page–provides a static contrast by which we can marvel at Delisle’s effortless line and proficiency with delivering whatever tone he chooses–kinetic action in “Rita,” genuine erotic heat in “Diane” and “Karine,” delightful and unexpected visual puns throughout (my favorite, I think, was “Irene,” where both of the title character’s arms slide out of her left socket as though they were connected through her shoulders like an axle). Delisle chronicles his own sexual neuroses and issues with as much candor and visual cleverness as you’re likely to see this side of John Cuneo’s similar project nEuROTIC.

On the other hand, it’s quite easy to read this book as savagely misogynistic in its repeated reduction of women to their constituent body parts, or its repeated depiction of staid portly women as literally holding the pneumatic sluts within themselves prisoner, or its repeated message that women are materialistic, hypocritical assholes who’d just as soon make men miserable for no reason as look at them, let alone fuck them. Men don’t come off that great either, but that’s usually because they were stupid enough to get involved with women in the first place. The tone gets so strident that it flattens out the sophistication and creativity of Delisle’s ideas–cleavage and vaginas swallowing men whole, a literal vagina dentata, yes yes, we get it. It’s entirely possible that this is all quite self-aware–the existence of the androcentric companion volume Albert and the Others would appear to indicate that, though I haven’t read the book itself–but it’s also entirely possible that that doesn’t matter, and that at a certain point putting your conflicted or outright hostile feelings toward women on display leads to reinforcing them rather than confronting them. I honestly don’t know. It’s a powerful comic book, I’ll give it that.

Comics Time: Daredevil #103 & #104

February 25, 2008Daredevil #103 & #104

Ed Brubaker, writer

Michael Lark, Paul Azaceta, and Stefano Gaudiano, artists, #103

Lark, Azaceta, Tom Palmer, and Gaudiano, artists #104

Marvel Comics, December 2007 & January 2008

32 pages

$2.99

Daredevil is writer Ed Brubaker’s most overlooked book at the moment. It’s not as rollickingly entertaining as his and Matt Fraction’s wild genre mish-mash The Immortal Iron Fist, it’s not as character-defining as his Captain America, it lacks the “book I’ve always dreamed of writing” vibe of Criminal, and it’s not part of a high-profile crossover like Uncanny X-Men. What’s more, unlike Iron Fist or Cap, Daredevil is also up against years-long high-quality runs on the character, by the likes of Frank Miller and Brubaker’s immediate predecessor on the title, Brian Michael Bendis. And one thing that came up repeatedly during my monthly discussions of the series while at Wizard is that it’s one of the least showy superhero titles around: with no stunts, no events, no reboots, it’s simply consistently good issue after issue, which bizarrely works to its detriment in terms of maintaining a high profile with critics and readers. That’s a shame, because man, this is a very satisfying masked-vigilante comic.

Forget Spider-Man/Peter Parker: Matt Murdock is Marvel’s true everyman hero. Not in the sense that he’s a dork who lives in his aunt’s basement, but in the sense that he’s someone who, but for his blindness and super-senses and ninja training and red pajamas, you feel like you could actually meet in New York City: a rich lapsed Catholic pussyhound lawyer who can’t stand losing. That regular-guy vibe is used quite well in Brubaker’s run: The character is constantly shown bouncing between his superheroic activities and his civilian ones, on an almost scene by scene basis, like superheroing is a job he just can’t leave at the office and affects his life accordingly.

More importantly, those superheroic activities consist almost solely of beating criminals until they do what he wants. (Another Wizard colleague once told me that you can always recognize a bad Batman story by whether or not he’s acting like Daredevil, i.e. solving cases with his fists instead of his brain.) Now, it shouldn’t be hard for anyone who’s lived through the past few years to make the connection that what our superheroes do all the time, our government has to ignore international human rights treaties to get away with. In keeping with that Marvel-realist tone, Brubaker tackles the torture aspect of Daredevil’s vigilante activities head-on in this storyline (a blowtorch factors in at one point), and the result leaves us feeling refreshingly uncomfortable with our ostensible hero. He also portrays supervillain-driven gang wars in a convincingly ground-level way, simply replacing the strategic use of an AK-47 or a well-orchestrated hit (or, if you prefer, appearances by Luca Brasi or Omar Little) with the arrival of the Wrecking Crew or the Enforcers.

He gets slightly less mileage out of Murdock’s tortured-as-always romance, this time with his villain-targeted wife Milla–forgivable, considered how well-worn that territory is for the character. I think perhaps he could have tried to ground her slide into dementia by couching it in the emotional language of losing a loved one to depression, alcoholism, Alzheimer’s, or some other more relatable mental disease; perhaps he’ll get there eventually. For now, as aided and abetted by the fits-this-writing-to-a-tee art of the team led by Michael Lark, he’s cranking out a heck of a superhero book anyway.

Comics Time: Teratoid Heights

February 22, 2008Teratoid Heights

Highwater Books, Summer 2003

Mat Brinkman, writer/artist

176 pages

$12.95

Buy it from Bodega Distribution

Originally written on March 8, 2004 for publication by The Comics Journal; a longer alternate version appeared on this blog

Cartoonist Mat Brinkman is the most compelling member of the Fort Thunder art collective, combining the whimsy and chops of a Brian Ralph with the weirdness and choppiness of a Brian Chippendale or a Jim Drain. And in this little book, he’s created a minor sequential-art masterpiece. This nearly wordless, black-and-white collection of short adventure stories, in which a variety of monstrous, faceless creatures explore their respective environments with alternately hilarious and frightening results, recalls Jim Woodring’s Frank stories, in its deft use of scary-funny black humor and unexpected surprises. But it eschews Woodring’s familiar funny-animal tropes for something new, eerie, and original. The art, which simultaneously possesses the starkness of woodcuts and the manic detail of the ’60s undergrounds, quite simply looks like a transmission from Another Place.

Each of Teratoid‘s subsections has its strengths: The wild wanderings of “Oaf” are notable for their emotional range and their visceral description of this fantasy world’s geography; The simply-drawn creatures of “The Micro-Minis” are like cartoon automatons, their actions flowing naturally from their own design as a function of the very mechanics of drawing them; The wordplay of “Cridges,” the book’s only non-silent section, show Brinkman to be as able and witty a manipulator of language for its own sake as he is of art. The book’s real tour-de-force, though, comes in the section called “Flapstack,” which concerns the subterranean realm of little creatures that look a lot like pulled teeth. That section’s story “Sunk” is, I think, the single best comics sequence I read all year. Three of the teeth creatures, each bound to the other by a length of rope, fall into a winding labyrinth. As they try to navigate this complex maze, Brinkman intercuts between them as though multiple cameras are involved. The three creatures are indistinguishable but for the corresponding numeral that appears each time they come back “on screen.” Before long we have a sense of exactly where in the maze each creature is, and it’s the intense concentration required to keep up with Brinkman’s byzantine constructions that attaches us to the creatures as surely as their frustratingly short lengths of rope attach them to each other. As they attempt to overcome the obstacles they encounter, the tension is, almost stunningly, an edge-of-your-seat affair. The powerful end to this thriller–which, again, stars three silent and indistinguishable walking teeth–is testament to the power of the medium when artists deploy it in new and sophisticated ways, and to Brinkman for having the vision to do.

Comics Time: The Would-Be Bridegrooms

February 20, 2008The Would-Be Bridegrooms

Shawn Cheng, writer/artist

Partyka, 2007

36 pages

$4

The most recent minicomic by my friend Shawn Cheng sees him continuing to mine his interest (obsession?) with bestial forms, particularly the almost manic detail found in art representing the mythical monsters of Native and South American cultures. As opposed to the bleakness of his Ignatz-nominated collaboration with Sara Edward-Corbett The Monkey and the Crab, this one is much more playful in nature, despite sharing with that earlier work a plot involving a game of one-upsmanship gone horribly awry. As his coyote and jackrabbit protagonists play their game of dueling transformations to impress the grandma of their prospective bride, the fun is in watching Cheng’s character designs evolve from knowingly lo-fi (dig the coyote’s first-grader triangle for a nose) to hilariously baroque. Quickly running out of ideas, the two would-be bridegrooms start repeating themselves, producing high-level video-game variants on earlier creatures they’ve transformed into (“DEMONIC Ice Giant!” “MUTANT White Bear!”); once they max out their imaginations with their absurdly complex World Serpent and Thunderbird creations, they pause, give up and simply start beating each other up. All this is smartly offset by the constant observing presence of the adorable little round-headed grandma. (Her startled squeal of “Oh!” upon seeing the first transformation tickled me pink.) It’s she who gets to deliver the story’s punchline/moral, which is that showoffs inevitably lessen themselves compared to the woman they intend to impress. It’s an appropriate ending for a neato little mini that uses an understated, perhaps even slight, narrative to, yes, impress.

Comics Time: The Beast Mother

February 18, 2008The Beast Mother

Eleanor Davis, writer/artist

Little House Comics, 2006

19 pages

$5.00

Vainly hope to buy it from Little House

Like The Wicker Man (the original, not the nightmarish Nic Cage version, and God am I tired of having to say that), this beautiful minicomic by the prodigiously talented artist Eleanor Davis smartly plays upon and then reverses the ingrained sympathies of the modern genre reader. What appears to be a simple, perhaps even simplistic fable about a maternal monster, a man with a gun, and how we kill what we don’t understand turns out, in a fairly grim (perhaps even Grimm) fashion, to carry almost precisely the opposite message, albeit with enough ambiguity to keep you uncomfortable long after you’ve finished.

Davis is a thrillingly precise artist. In a slightly different world her art might have drifted into the overly slick style of the Flight school of animation refugees; instead it stops short of their cold cartoonishness thanks to unexpected touches of vulnerability in the character design and figure work (she’s Young Comics’ preeminent poet of breasts and body hair), yet without sacrificing a sense that every line is going exactly where she wants it to. Her use of black is powerful, guiding the eye around her immaculately composed layouts and as strongly delineated as the mini’s ridiculously attractive die-cut cover. Best of all she ends the thing with no fuss or fanfare–nasty, brutish, short, and highly recommended.

Comics Time: Captain America #33 & #34

February 15, 2008Captain America #33 & #34

Ed Brubaker, writer

Steve Epting, artist

Marvel Comics, December 2007 & January 2008

24 pages, $2.99 each

What can you say about a series that in one issue sees a disembodied cybernetic arm spring to life and effect a prison break like the Addams Family’s Thing on steroids, and in the next sees protests over mortgage foreclosures and high gas prices lead to a brainwashed squad of S.H.I.E.L.D. agents opening fire on unarmed civilians outside the White House? Taken together these two scenes illustrate the best thing about Ed Brubaker’s run on Captain America, which itself may well be the best thing ever to be done with the character: It blends all the disparate Captain America flavors—two-fisted World War II hero, star-spangled costumed superhero, Steranko superspy, gritty black-ops badass, American icon, Marvel Universe elder statesman, post-9/11 symbol of Where We Are As A Nation—into a smoothie of pure action-adventure satisfaction.

Of course, since his “death” (sorry, can’t help but put it in quotes) in the series a few months back, Cap himself is nowhere to be found in the book that bears his name, and everyone and their grandmother will tell you it’s a testament to the handle Brubaker has on the cast of supporting quasi-super characters–Sharon Carter/Agent 13, Bucky/The Winter Soldier, the Falcon, Black Widow, Iron Man, Nick Fury, Union Jack, Spitfire, the Red Skull, Doctor Faustus, Arnim Zola–that the book remains eminently readable. Everyone and their grandmother is actually wrong, but only because the way they’re framing the issue is so silly: I understand the expectations inherent in the concept of “title character,” but Brubaker is a skilled craftsman and so are his main artists on this title, Steve Epting and Mike Perkins, so the notion that the death of Steve Rogers–in terms of superhero secret-identity complexity, we’re not talking Peter Parker or Bruce Wayne here–would scotch the whole affair reminds me of that Seinfeld routine where he says that people who get passionate about their local sports teams are essentially rooting for laundry. No, what’s impressive about the continued quality of this series is Brubaker’s grip on the tone–how the absence of Cap has seemed only to intensify Brubaker’s abilities to draw from the strengths of all the aforementioned aspects of the character by extending them to his entire milieu. This sleight of hand is so deft that you’re so caught up with the cloak-and-dagger stuff involving various superpowered people infiltrating AIM and RAID and Kronas and so on that when the entirely organic-feeling results of those organizations’ schemes–the destabilization of the American economy via problems we in the real world are currently facing in slightly less intense forms–come to light, you’re just staggered by how appropriate it feels, even in a book where a major supporting character has the mutant ability to talk to birds. Heck, the guy even gets something interesting out of Mark Millar’s astonishingly stupid Civil War plot by playing the victorious Iron Man as a conqueror with a conscience.

The big hook in issue #34 is that Cap’s old sidekick and current ex-Manchurian Candidate, Bucky, has now assumed the Captain America mantle. I don’t really understand why his new suit is shiny, other than it gives designer Alex Ross an excuse to bathe his paintings of it in even more sourceless white glow than usual, but who cares? He makes an interesting candidate for the position because unlike Rogers, who could only grieve over the horrors of the world, Bucky, like America itself, has actually committed a few. Now he’s trying to make up for it, and hey, we can relate, I think.

The festivities in these issues are underpinned by Epting’s muscular, much-imitated noirish stylings. His action choreography is impeccably intelligible, his punches feel like physical things, and he clearly has a great time with the costumes, uniforms, and tech that give the book its superheroic sheen even as he dirties it up with unidealized faces and blacks galore. His Red Skull is intimidating as heck, too; thanks to the plotline, it’s once again a mask rather than a guy with a skull for a face, and those normal eyes peeking out from behind all that latex or whatever it is are reminiscent of those shots in Texas Chain Saw where you can see Leatherface’s peepers rolling around beneath the mask. He’s creepy, in other words, and makes a great enemy for one of the three or four best superhero titles on the market today.

Comics Time: Goddess Head

February 13, 2008Goddess Head

Dash Shaw, writer/artist

Teenage Dinosaur Press, 2006

100 pages

$11.99

Buy it from the Poopsheet Shop

In theory I should love this book. A collection of various shorts from 2002-2004, it more or less epitomizes the abstract short-form comics that so excite me–an emphasis on repetition and rhythm, a disconnect (syncopation?) between text and image, figures and patterns bearing equal emotional and narrative weight, a pointed lack of “this means this, that means that” allegory or straightforward storytelling, emotionally rather than intellectually intelligible content. And yet it leaves me cold, both on its own terms and when compared to the Kevin Huizenga, Anders Nilsen, and John Hankiewicz comics of this sort that I find myself constantly returning to. Shaw’s line seems uncertain, frequently unattractive but for no discernible purpose, done this way out of lack of craft rather than intentionality. His stream of consciousness flows too frequently into the shallow waters of shock-value sexuality and easy self-reflexivity, neither of which seem to serve much purpose other than announcing themselves. The end result is scattershot, like it’s trying to do too much at once. The best work here is the lyrically minimalist day-in-the-life comic that concludes the volume, “Cheese”–the line shapes up, the visual language is clever (a one-panel shower scene riffs on the familiar breast self exam diagrams found in college dorm bathrooms everywhere) and, in the concluding sequence that uses the arching and flattening of a single line to signify the onset of sleep, quite poetic and beautiful. It displays the focus the rest of the book lacks. I think there’s enormous potential here–that he chose to do this kind of comics at all would indicate that–and obviously he’s got several more years worth of work under his belt at this point. But for now it’s not quite there.

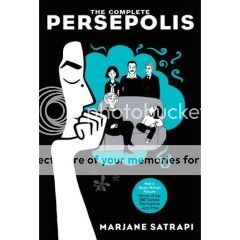

Comics Time: The Complete Persepolis

February 11, 2008The Complete Persepolis

Marjane Satrapi, writer/artist

Pantheon, October 2007

352 pages

$24.95

The first two-fifths or so of The Complete Persepolis is a pleasurable, even gripping read, coming across like a ground-level view of a real-world 1984 played as farce instead of tragedy. The euphoria of revolution giving way to factionalism and repression, the first ominous signs that something really bad is on the way, the lack of a coherent “and then this leader did this and this city did this” historical through-line (the Ayatollah Khomeini is never mentioned or even alluded to), the story told instead through only the glimpses of the avalanche of history available to a little girl—all this is reminiscent of Winston Smith’s memories of the dawn of Ingsoc and Big Brother in Orwell’s dystopian masterpiece. In this way Persepolis does those of us on the outside of Oceania Iran a great service as it reveals that this regime’s thought police is a miserable failure: Beneath the veils and behind closed doors, people live the most normal, hopeful, free lives they possibly can. The breezy cartooning and young Marjane’s precociousness leaven the proceedings with the kind of humor you’ve got to figure is anathema to the benighted thugs who’ve forced otherwise regular people into an ongoing nightmare of political prisons, bloody fanaticism, and hypocritical sexual repression.

But when the second chunk of the story rolls around, the seams start to show. Teen Marjane’s misadventures in Europe are a lot less compelling as narrative than li’l Marjane’s Revolutionary childhood–they’re not a whole lot more exciting than any kid you ever knew who smoked weed a lot in high school, in fact. And it’s at that point that you start to really notice the weakness of Satrapi’s cartooning. Her line seems chunky but without purpose, like it’s simply out of shape, while she either has the most limited ability to draw clothes and figures I’ve ever seen or she actually does know more people who dress head to toe in black all the time than you’d find in the audiences shown in Depeche Mode 101. Juxtapose both aspects of her art with the frames of the animated feature based on the book that populate this edition’s cover and the comparison is not flattering to the source material: The cartoon’s line is cleaner, the character designs tighter, and the graytones give the backgrounds (frequently nonexistent in the book itself) a lush life of their own. Satrapi also proves to be an unreliable editor for her own biography, as a lot of the juiciest material (losing her virginity, dealing drugs, the “hours of hallucinations” she suffered after a suicide attempt) are almost completely elided, in favor of countless stories about how tedious she finds her friends. (Hey, I’m with her there!) The book rambles on structurelessly, but not in a way that evokes the randomness of life–it’s all just there, and then it all just stops. The bummer of it is that when it does, you can still remember a time earlier on when you would have wished it didn’t.