Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

Comics Time: Boy’s Club

May 12, 2008Boy’s Club

Matt Furie, writer/artist

Teenage Dinosaur, 2006

40 pages

$5

This is one of the funniest comic books I’ve ever read. The closest thing I can compare it to is the music of the cock-mock-rock band Electric Six; both take the absolute lamest aspects of rokkin’-out culture–bad drugs, bad booze, bad food, bad jobs, bad taste–and po’-facedly present them like features of that lifestyle rather than bugs. Instead of phony rock gods, the main characters of Boy’s Club are a quartet of ’80s-style funny-animal cool dudes with all the right moves, like a cross between Bill & Ted, the Tri-Lams, and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Many of the funniest gags center on their cliché-heavy responses to absurd situations–lots of big grins and thumbs up, statements like “oh snap!” and “it’s a free country” and “peace out!”, words like “amigo” and “awesome,” and so on. Meanwhile, the visuals come across like a sitcom version of Paper Rad, frequently riffing on drug experiences to pull of non sequitur sight gags like one character’s face melting off or morphing into Falcor from The Neverending Story. The best jokes–and in this book, that means they’re pretty goddamn great–combine goofball visuals with that deadpan duuuude humor: a six-panel grid of reaction shots to a particularly huge hero sandwich, a character’s response to finding another character’s vomit in the bathroom sink. They’re kind of like Achewood if that strip were done by the guy your roommate bought pot from in college rather than a software designer. It’s the kind of comic you’ll stick in friends’ hands and force them to read it. If you like humor comics I really can’t recommend it highly enough.

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 10: Winter/Spring 2008

May 9, 2008Mome Vol. 10: Winter/Spring 2008

Al Columbia, Sophie Crumb, Dash Shaw, Ray Fenwick, Émile Bravo, Jim Woodring, Robert Goodin, John Hankiewicz, Tom Kaczynski, Jeremy Eaton, Kurt Wolfgang, Paul Hornschemeier, Tim Hensley, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds & Gary Groth, editors

Fantagraphics, December 2007

120 pages

$14.95

Mome Vol. 10 by contributor, in order of appearance:

* Al Columbia’s gorgeous and frightening front cover is so great that I found myself trying to justify the “someone’s about to torture an animal” back cover image, where normally I’d just say “fuck that shit.”

* I really like the ink and watercolor portrait that is Sophie Crumb’s first contribution to this volume. Her comics, though, are more of the smug writing and unpleasant art that have put me off of her work in past volumes.

* Dash Shaw’s science-fiction story is my favorite thing by him I’ve seen so far. I feel like his lo-fi diagrammatic art and layouts are really clicking here, while the storyline’s central conceit of a man who comes from a world where time runs backwards is ambitiously complex and demands Shaw be inventive in solving the problems it presents him with visually. The use of color is measured and smart, and there’s a weird pathos to both the ideas and the way Shaw draws the characters. I could imagine Kevin Huizenga doing a wicked cover version of this strip.

* Ray Fenwick does his sublime/ridiculous prose/subject matter juxtaposition thing again and I don’t think it works all that well here. Celebreality gossip culture is a soft target.

* Émile Bravo does another sociopolitical pictographical parodical morality play involving various ethnicities’ views of those below their rung in the social hierarchy; it’s a sensible idea but not something that blows you away with its insight, and I think he undercuts it slightly with the punchline.

* In the conclusion to Jim Woodring’s “The Lute String,” Pupshaw and Pushpaw are punished by the elephant god for their transgressions by being sent to Earth Prime! It’s as much fun looking at Woodring’s art as it is seeing this pair of pranksters get their comeuppance, and meanwhile it’s really odd and funny to see Woodring draw normal people. That punchline panel is a scream.

* I really like the way Robert Goodin draws people, with big forearms reminiscent of Popeye and really unique facial designs. I’ve seen world-culture myths adapted before, of course, and this Indian shaggy-dog story doesn’t stand out all that much in terms of the moral imparted or the mechanics of getting there, except for that lovely art.

* John Hankiewicz’s debut Mome contribution is a doozy. The narrated story, a tale of a gentrifying neighborhood reminiscent of Tom Kaczynski’s contribution to Vol. 9, draws attention to Hankiewicz’s finely detailed environments and thus heightens the frisson of seeing three very different types of figures moved through it by the cartoonist: a fairly realistic representation of the narrator and (I think) his father; a giant-headed, Tweedle-Dee/Tweedle-Dum-esque couple whose out-of-scale-ness represents the gaily crass nouveau riche new inhabitants of the neighborhood–in one memorable panel, they appear totally and disconcertingly naked; and a thickly delineated, faceless abstraction of a female, symbolyzing the anonymous self-mutilator whose weblog or livejournal the narrator habitually visits. It’s this strip I’ll return to, no doubt.

* I was going to say something like “Tom Kaczynski returns to the familiar territory of industrial/commercial environments altering people’s internal landscape,” and then I thought how funny it is that a subject like that is familiar territory for someone. I’m grateful that’s the case even though I don’t think it’s all quite cohered to the level of power he hopes for yet. This one comes close, but for some reason I think it would have worked better if it were longer and had more time to build up to the ending.

* Jeremy Eaton’s art is text-heavy and really loose, Stieg-esque I suppose. I’m not 100% sold on his short-story-ish tale of a retarded man accused of a gruesome crime, and I’m not sure the limited scope of his layouts gives his loose line enough room to breathe and really have an impact, but I’d like to see more.

* This is my favorite chapter of Kurt Wolfgang’s “Nothing Eve” so far. It’s replete with insightful observations about crowd dynamics, and a funny (if slightly overwritten) wink at how Hollywood inflects our view of how momentous occasions are supposed to unfold.

* Paul Hornschemeier’s heroine gives her one-night-stand the kiss-off in this installment of “Life with Mr. Dangerous,” and I think the scene plays realistically and uncomfortably. But Amy’s affect is so flat and her reasons for being such a downer all the time so underexplored that it seems to me like it’ll be really hard for her to hold our interest as a main character in an eventual collection of this story; I found myself agreeing with her gossipy coworker’s harsh assessment of her even while I thought the coworker herself was a bit too one-dimensionally glib.

* The punchline panel for Tim Hensley’s sole Wally Gropius strip this volume continues the disturbingly violent undercurrent he kicked off with the Jillian/incest strip last ish, and also serves as a rejoinder to the callous Columbia image that follows on the back cover.

* As is the case with pretty much every volume of Mome, it’s tough to imagine a better value for your alternative comics-buying dollar. The range in tone, style, subject matter, and even quality makes it a uniquely bracing quarterly(ish) view of the state of the art.

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 9: Fall 2007

May 7, 2008Mome Vol. 9: Fall 2007

Ray Fenwick, Tim Hensley, Al Columbia, Eleanor Davis, Jim Woodring, Gabrielle Bell, Andrice Arp, Joe Kimball, Mike Scheer, Tom Kaczynski, Brian Evenson & Zak Sally, Kurt Wolfgang, Paul Hornschemeier, Sophie Crumb, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds & Gary Groth, editors

Fantagraphics, October 2007

120 pages

$14.95

Mome Vol. 9 by contributor, in order of appearance:

* Ray Fenwick’s text-heavy pin-up pages, drawn on the dismembered back covers of old hardcover books, mostly do that ironic combination of grandiose language and quotidian concerns, but for my money his best gags are the simplest. His “FUCK YOU AND YOUR BLOG” page, where that line of text is juxtaposed with a jauntily floating balloon, is a little easy but still made me think of scanning it and posting it on message boards; the conclusion of his first piece, which states that your estranged former best friend is “not available for comment,” hit me like a punch in the gut.

* Tim Hensley’s Wally Gropius strips have always been both funny and interesting to me in their absurdist, angular deconstruction of old Archie visual and narrative tropes, but I think this is the volume where they really made me sit up and take notice. The panel to panel physical business in the library-based strip “Shh!” is a delight to behold, and the incestuous conclusion to “Jillian in ‘The Argument'” is a note-perfect, savage lampoon of Sam-and-Diane-style “enemies become lovers” rom-com rhythms.

* Al Columbia can draw like a motherfucker but that’s really the only thing I got out of his Hansel & Gretel pastiche. Aside from the kiddie-killer’s creepy face it wasn’t really funny or scary.

* Eleanor Davis’s tale of two brothers and the abandoned house they discover in the woods reads like a cross between her usual monster-myth beat and the observational-drama family matters of her minicomic Mattie & Dodi. I’d probably still prefer the straight-up former to a combination of the two. However, Davis’s ambiguous treatment of what the brothers experience in the house and the casual fraternal violence of its aftermath is certainly unsettling.

* The first half of Jim Woodring’s “The Lute String” is a bonanza of adorably mischievous drawings of Pupshaw and Pushpaw, weird fungal creatures and transformations that gently trigger a phobia I have about growths, and a portrait of what God looks like in the world of Frank. (He’s an elephant!) Woodring comics are funny and scary and beautiful and look like Woodring comics and nothing else, which is a colossal achievement.

* I don’t get why Gabrielle Bell spots blacks the way she does. It clutters the image and distracts from the rhythm of the page.

* Andrice Arp does her own thing with another adaptation of a pre-Revolutionary War anti-English broadside. What’s interesting about these is how astutely they simulate what comics probably would have looked like had comics proper been around at that time, not just in terms of the character designs and typography but the metaphorical visual vocabulary itself–a haughty English captain vomiting his heavily taxed tea down the throats of helpless colonists, for example.

* Joe Kimball’s vertiginous page layouts and masterful graytones maintain the eerie air of his previous contribution to the series, but the comparatively straightforward visuals and storyline–involving an old man returning to his vampiric lover for one last embrace–reveal limitations in his figurework and storytelling.

* Mike Scheer’s art is indeed astonishingly lush given that it was created in ballpoint pen, but beyond that I don’t connect with it. I like the overly long titles he gives each piece, though.

* Tom Kaczynksi’s vaguely Ballardian tale of a young couple traumatized by the construction of a high-rise condo in their ersatz neighborhood is another of his capitalist cautionary tales, and like the earlier ones it somehow never feels didactic despite the potential for lecturing or hectoring. I think it might be because he is primarily concerned with the emotional impact of consumer society rather than the political, philosophical, or economic impact. The narration is just shy of hard-boiled, which is funny, and placing his story right after one of Bell’s makes for an interesting contrast in terms of how the two artists differ in their depictions of urban ennui–Kaczynski is colder and sharper, and while his characters lack the warmth of Bell’s his pages convey their information more dynamically and convincingly.

* Zak Sally’s adaptation of horror writer Brian Evenson’s shifting-identity body-horror story “Dread” is a case of designy typography overwhelming whatever power the story itself might have had.

* At this point Kurt Wolfgang’s Bagge-esque cartooning is almost as out of place in Mome visually as Sophie Crumb, and it’s not the kind of style I gravitate to naturally, but the fact that his story’s premise is “last night before the end of the world” is a hell of a way to keep you eagerly coming back in anticipation of the climax. With my luck nothing will happen.

* This is the most effective chapter of Paul Hornschemeier’s “Life with Mr. Dangerous” so far, and not just because of the nudity–I just really liked the panel where our heroine’s murmur of “I’m sorry” to her absent boyfriend is partially drowned out by her one-night-stand’s snores.

* Sophie Crumb…I don’t see the appeal.

Comics Time: New X-Men Vol. 6: Planet X & New X-Men Vol. 7: Here Comes Tomorrow

May 5, 2008New X-Men Volume 6: Planet X

Grant Morrison, writer

Phil Jimenez, artist

Marvel, 2004

128 pages

$12.99

New X-Men Volume 7: Here Comes Tomorrow

Grant Morrison, writer

Marc Silvestri, artist

Marvel, 2004

112 pages

$10.99

Originally written on July 19, 2004 for publication in The Comics Journal

Grant Morrison is the X-Men franchise’s angel of mercy. In the two decades since Chris Claremont transformed a third-tier Stan’n’Jack creation into the most popular concept in North American comic books, no greater act of love has been committed on behalf of mutantkind than the truly mighty act of deadwood clearance that was Morrison’s much-heralded run on New X-Men. Culminating in the issues collected in the trade paperbacks Planet X and Here Comes Tomorrow, Morrison’s labor of love meant killing not just characters but concepts, entire ways of writing both the X-Men and superhero comics in general. The posturing villains, the alternate futures, the constant battles, the tortured soap operatics, even the costumes (easily the ugliest in all of superherodom, by the way)–for this potentially fascinating heroic-fantasy concept to be fascinating once again, Morrison says, we’ve got to wipe out everything they’ve come to be known for and start over. And it worked. Naturally, the House of Ideas undid nearly all of it within a month of Morrison’s departure.

Morrison refers to his four-year run on the title as one giant graphic novel; Planet X and Here Comes Tomorrow are the concluding chapters, and as such tie together nearly every loose end of theme and plot left dangling during his incredibly dense tenure. The big reveal that sets this final act in motion is the discovery that Xorn, the Chinese X-Man and healer with a star for a brain (!), is in actuality Magneto, the X-Men’s nemesis, presumed dead in an anti-mutant genocide that kicked off Morrison’s run. In the guise of the gentle Xorn, Magneto has exerted his influence over the Xavier Institute’s “special class” of ugly, poorly adjusted mutant teenagers, while simultaneously sowing the seeds of discontent and death among the X-Men themselves in the form of everything from extramarital affairs to widespread drug abuse. We’ve seen Magneto come back from the dead before, but we know we’re in uncharted territory when his first post-unmasking act is to quite literally destroy Manhattan. (This was sign number one that Marvel would be hitting the big red reset button once Morrison defected to DC. Where’s Spider-Man going to fight Doctor Octopus–Hoboken?)

Despite giving the preening bad guy his brightest moment in the sun, Morrison’s aim with Planet X is to savagely mock the character to the point where the last vestiges of appeal in his violent brand of sci-fi identity politics are erased. Magneto, who throughout the series had become a beloved martyr figure, his image appearing on the t-shirts and bedroom walls of disaffected mutant youths everywhere, quickly finds that he lacks the vision thing. His new “subjects” have seen him die and return so many times they don’t believe it’s actually him now. The special class, unwitting members of the new Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, either prefer Xorn outright or just think it’s kinda queer for their fearless leader to have dressed up in costume for months. In one hilarious sequence, the self-styled Master of Magnetism launches into a rousing speech so grandiosely Shakespearean that one can hear the mellifluous voice of Sir Ian McKellen proclaiming it in the next X-movie, only to be told by his henchman Toad that the masses can’t even hear him, seeing as they’re milling about in the street and he’s inside the upper floors of the Chrysler Building. Throughout this volume Morrison displays a genuine comedic gift, particularly in contrast to superhero writers whose idea of a gag is to have Ant Man crawl up his wife’s vagina. Morrison has said in interviews that his brutally satirical treatment of Magneto was a condemnatory reaction against the so-called nobility of a character who is nothing more than a murdering terrorist. It’s a welcome point of view even here in the real world, where we’ve so often been beseeched to “understand” the inexcusable, and where ostensible humanists serve as apologists for benighted fundamentalist slaughter.

Phil Jimenez, a solid if not thrilling artist of the George Pèrez school whose talent (besides drawing a fierce Jean Grey) lies in evoking superhero classicisms well enough to be able to subvert them too, draws Magneto throughout as an eight-foot-tall, floating, purple Darth Vader, but transforms his right-hand man Toad into the type of hip London scumbag who sells E outside of Sophisticats. Before long, the increasingly impotent potentate is addicted to Kick, the mutant club drug/performance enhancer. Bereft of new ideas, he begins dredging up idiotic schemes from X-books past, like reversing the world’s magnetic poles, a move as sure to kill mutants as it is to kill everyone else. By the time this pathetic old asshole finally gets his comeuppance (at the claws of Wolverine, naturally), his long-time rival Professor X has dismissed Magneto’s ossified, coercive philosophies utterly: “…the worst thing you ever did,” he tells the would-be dictator, “is come back.” Or as the stylish living weapon Fantomex puts it to the villain, “Is everything you say a cliché?” Adamantium claws may cut off your head, but having your self-created legend deflated really hurts.

Here Comes Tomorrow is to dystopian-future X-stories what Planet X was to Magneto stories: the final word. Readers of blockbuster superhero titles like Paul Jenkins’s Wolverine: Origin or Jeph Loeb’s Batman: Hush can tell you that while throwing a shock reveal into your story is easy, doing it in a way that’s supported at all by what’s come before, that’s both difficult to figure out before the reveal and impossible to miss afterwards, that enriches your understanding and enjoyment of what you’ve already read, and that generally doesn’t make you want to punch yourself in the face is apparently beyond the ken of most mainstream writers. Not so with Morrison, who after his surprise resurrection of Magneto in Planet X reveals a puppet master behind not just the once-again-dead magnetic supervillain but nearly every bad thing that went down in Morrison’s run and beyond. The “intelligent bacterial colony” known as Sublime was the very first form of life on Earth, and has labored for three billion years to stay at the top of the evolutionary ladder. The inherently powerful and fabulous mutants are the only true threat to Sublime’s self-confidence; he therefore worked behind the scenes in various guises to make sure that mutants were too busy getting killed by both humans and each other to realize their true potential for greatness. Here Comes Tomorrow takes place 150 years in the future, a time in which Sublime is preparing his final assault on the lifeforms of Earth by resurrecting the omnipotent and destructive Phoenix (aka Jean Grey), who was killed by Magneto in a final act of defiance just before his own execution.

If your eyes are already glossing over from simply reading a description of the hoary X-concepts being trotted out here, hang in there. (And ignore the fact that this arc marks the return to Marvel of early-90s superstar artist and Image co-founder Marc Silvestri. I’ve never been wild about the hyperrendered style of Silvestri, Jim Lee, and the like, but nor am I morally offended by it, as are some observers of the scene. There are a few storytelling lapses here–it would have been nice if the oft-mentioned White Hot Room in which the Phoenix resides was actually, y’know, white–but they’re mainly out of Silvestri’s hands. For what it’s worth, I think his style works rather beautifully here, cranking up the intentional superheroic/supervillainous clichés to eleven and giving this crazed, patchwork future a rough-hewn glamour and muscular sex appeal. His Wolverine, for instance, is both a man who is believably ready to die and a man with an unbelievable ass.)

What truly separates Morrison’s story from every other all-powerful-villain-in-a-future-we-may-be-too-late-to-prevent tale you’ve come across is not just his proficiency in generating stunning sci-fi concepts (the Termids, the Crawlers, the Feeders, the Phoenix Corps (!)) or instantly riveting characters (the Proud People (complete with Magic Car and Mer-Max the talking whale), Tom Skylark and Rover, Appollyon the Destroyer), though indeed introducing all of these in a four-issue arc whose world we’ll likely never see again is equivalent to throwing a gauntlet in the face of other writers of imaginative comic-book fiction. (See Morrison’s Seaguy for a similar act of “I’ll see you and raise.”) No, the strength of this book, and of Morrison’s entire tenure with the characters, is his belief that love trumps the horror of the world, and his ability to convey this in a way that’s emotionally direct without being trite or mawkish. It’s Dr. Hank “Beast” McCoy’s heartbreak over his own lies that gives Sublime an entrée, and Scott “Cyclops” Summers’ refusal to let go of a failed love with Jean Grey that ensures Sublime’s success; in the end, it’s connections that are just as personal–between ugly Ernst and disembodied Martha, between the identical triplet Stepford Cuckoos, between human Tom Skylark, his Sentinel parent Rover, and his robotic lover EVA, between the near-immortal Wolverine and his beloved Jean Grey–that set Sublime up for the fall. And it’s Jean Grey’s love for Cyclops, great enough for her to rewrite history and let him admit his own love for her one-time rival Emma Frost, that fixes “the hole at the heart of creation” and undoes Sublime’s machinations once and for all.

Morrison rode into New X-Men at the crest of a wave that saw Marvel taking bold risks with its core characters and ushering in a new writer-driven era of good, and even great, superhero comics; he rode out as persona non grata, his celestially vast ideas out of joint with a newly conservative company aiming mainly either to mimic the methods of blockbuster action cinema or mine fanboy nostalgia. He intended his forty-issue X-Men novel to be a gift to the franchise, but the gift has gone mainly unopened: Most of his new supporting cast has been shuffled offstage, the profoundly fresh relationship between Cyclops and Emma Frost seems poised for the chopping block, and eternal X-scribe Chris Claremont resurrected Magneto almost before Morrison had a chance to leave the building, pegging the villain’s whole Manhattan meltdown on the work of an impostor. (Would that we could place blame for the past twenty years of X-Men comics on a similar entity.) But we the readers are left with one of the most humanistic, richest, funnest, greatest superhero comics ever written. That’s gift enough.

Comics Time: DC Universe #0

May 2, 2008DC Universe #0

Grant Morrison, Geoff Johns, writers

George Pèrez, Doug Mahnke, Tony S. Daniel, Ivan Reis, Aaron Lopresti, Philip Tan, Ed Benes, Carlos Pacheco, JG Jones, artists

DC Comics, April 2008

32 pages

50 cents

Four of the six* ongoing DC-published superhero titles I read are written by Grant Morrison and Geoff Johns. The former is as engaging as ever in All Star Superman and Batman (which reads better in chunks than it does in monthly installments), while the latter has truly come into his own with Green Lantern and the Superman series Action Comics (both of which are at this point my all-time favorite main-line runs of their respective lead characters). Morrison, for his part, is my favorite superhero writer, and I enjoyed his earlier collaboration with Johns on 52. So despite having no interest in Countdown to Final Crisis and some innate resistance to the DC approach to crossovers–they tend to be epic discussions of comics-y concepts like continuity and multiverses, as opposed to Marvel’s tendency to root its events, however perfunctorily, in more familiar ideas like the privacy/security tradeoff or post-9/11 paranoia or whether the ends justify the means–I naturally gave this book a whirl based on my appreciation of its writers. I even brought home a copy since Jim Hanley’s was giving them away for free!

It’s a fun book. I don’t think I knew that it was going to be a collection of teases for upcoming storylines rather than a self-contained story, or even a coherent prologue to a larger story. But this approach seemed like a smart way to get across several things:

1) The DCU is heading in a unified direction…

2) …dictated by storylines involving the big iconic characters rather than Donna Troy and the Pied Piper…

3) …and written by Grant Morrison and Geoff Johns rather than Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray. Heck, given the reception of Countdown and its countless spinoffs, even Greg Rucka and Gail Simone, who are riding shotgun with vaguely connected tie-ins, seem like a huge deal.

DC Universe #0 seems to show that DC recognizes that its core characters/franchises (Batman, Superman, Green Lantern, perhaps Wonder Woman) are all pretty strong right now, so why not recalibrate the company’s crossover mojo around them rather than trying to force people to be interested in peripheral nonsense about nobodies? So instead of Monarch and Jason Todd, you get Batman grilling the ever-creepier Joker about a long-running plot thread involving a godlike supervillain gunning for the Dark Knight. You get one of Johns’s now-trademark multi-panel rapid-fire tastes of the rainbow of power rings now zipping around outer space. You get Superman in the future with the Legion of Super-Heroes (a concept I really don’t cotton to, but Johns has earned some credit in this department with his most recent Action arc), preparing to do battle with the hilarious fanboy-entitlement metaphor Superman-Prime. You get Wonder Woman’s godly forebears preparing to replace her with an army of 300 knockoffs, which makes for a funny visual at least. You get a creepy villain holding the scales of justice and trying to recruit other villains into yet another version of the Secret Society of Super-Villains, this one a Scientologyesque cult presumably dedicated to the awesome Jack Kirby villain Darkseid. You get an obliquely established return of Barry Allen, the long-dead Silver Age Flash, that plays itself out primarily through the shifting tone (and colors) of the narrative captions; it’s pretty funny to see Morrison do a mainstream-press-worthy character revival the same way he might establish an obscure plot point like, say, the link between the Undying Don and Ali-Ka-Zoom in Seven Soldiers. And you get the Spectre, but hey, they can’t all be winners.

As might already be apparent, the book is written in the crazy million-things-happening-at-once style of Morrison’s JLA Classified, Seven Soldiers, and those acid-flashback Batman issues from a few months ago, Johns’s Action Comics Annual and Sinestro Corps Special, and the pair’s 52. It’s possible to see the seams between the two writers’ work from time to time, but it takes some doing. I’m really happy to see Johns genuinely collaborating with Morrison and holding his own–it’s worth it for the horrified reaction of blogosphere snobs alone.

The art, needless to say, is of varying effectiveness. (Ivan Reis does what Ed Benes would like to do much better than Benes actually does, for example.) I think the George Pèrez cover is ugly and unnecessarily retro. However, I do like the design of the house-ad teaser pages interspersed throughout the comic to tout the relevant tie-ins–the text so blocky and matter of fact it’s almost funny. And they beat the hell out of either those orange Countdown-slogan teasers or the previous wave of motivational-poster-style teasers.

That being said, the notion that this is at all accessible to someone who isn’t a giant nerd is laughable. But I don’t care, since I am a giant nerd and I don’t give a shit about this particular book attracting new readers. That’s what manga is for! And even then we’re only talking about the first volume in a given series. I think the myth that “every issue should be written like it’s somebody’s first so that superhero comics would be more accessible” might make sense from a publishing perspective, but not necesarily a storytelling one, and maybe not even a publishing one anymore either given who the audience really is. I mean, any given fourth-season episode of Lost or Battlestar Galactica is completely incomprehensible to people who haven’t been following along, yet we fans don’t complain about that because we are fans and that’s who the shows are aimed at. Nobody gets upset because Death Note Vol. 7 isn’t a good jumping-on point, because that volume is for preexisting Death Note fans. Virtually everyone who picks up a comic called DC Universe is going to be someone who is already familiar with what a shared universe is, and that is totally fine. Now, the big corporate superhero companies can claim that the goal of something like DCU #0 is going to woo Johnny Dailynewsreader, but we don’t have to play along by evaluating the book negatively based on that standard. The standard I evaluated it on is “here’s a book by two of my favorite writers at DC that leads into their upcoming storylines on various titles–does it make me happy I’m reading them?” The answer was yes.

* All Star Batman & Robin, the Boy Wonder and Ex Machina

Comics Time: Black Ghost Apple Factory

April 30, 2008Black Ghost Apple Factory

Jeremy Tinder, writer/artist

Top Shelf, 2006

48 pages

$5

Jeremy Tinder’s debut graphic novella Cry Yourself to Sleep displayed a knack for slightly off-kilter observational humor, a fine grasp on cute character designs, and an entertaining way of combining the two. Stripped of that longer effort’s stabs at coaxing something deeper out of the yuks, BGAF feels slighter (is slighter, I suppose), but compensates for that by reading like a funny Jeffery Brown convention mini. Several of the short strips contained here mine familiar “cute animal is actually a vulgar cad” territory to laugh-out-loud effect–I particularly liked the shot of a nude woman fellating a bunny rabbit with such enthusiasm she looks like she’s eating his crotch. The stand-out strip, though, is the most serious one, which centers on a love quadrangle involving a lovelorn elephant. In its eight pages of anthropomorphized friends/lovers sharing one last bittersweet night before a separation, you get something that reads like half-Chunky Rice parody, half-Chunky Rice tribute. That’s a pretty enjoyable combination for this reader.

Comics Time: Batman and the Monster Men

April 28, 2008Batman and the Monster Men

Matt Wagner, writer/artist

DC, August 2006

144 pages

$14.99

A retelling of the first Batman story to involve superpowered antagonists way back when, Batman and the Monster Men would be the baseline of quality for Batcomics in a better world than this one. It’s unlikely to stick in your craw in terms of its depiction of Batman’s sadness or mania, which for me at least is the effect achieved by the best Batman stories. Nor does the scripting necessarily rise above the usual comic-book treatment of such stock figures as Mad Scientist, Gotham Mobster, Spunky but Naive Heiress, Crooked Commissioner and so on. The narration tends to spell out what’s happening and why, and the prose isn’t stylish enough for me not to be bugged by that. And Wagner’s art is sometimes startling crude.

But–well, if you’ve stuck around long enough to hear the “but” in the first place, my guess is this book may be for you. Reason number one would be Wagner’s art, crudeness and all. His Batman is a big hunk of marble that throws itself at its targets with a real wallop. Though we’re about as far from Paul Pope’s fashion-textbook realism, the combination of Wagner’s meaty design and Dave Stewart’s plain black and gray color scheme for the outfit truly makes Batman feel like a big, fast guy who puts on a creepy outfit to punch people in. Given that the threat in the story is basically three or four big huge mutants who punch people too, the effect is sort of like watching a Kimbo Slice streetfighting video on YouTube. That’s pretty much how I want a Batman comic to feel.

Wagner also somehow pulls off the delicate alchemy of the “detective” aspect of Batman’s idiom, having the character follow a trail of clues that we of course would never trace to the same conclusion but never coming across as manipulative or shoddily constructed. If the whole thing kind of pales in comparison to Frank Miller and David Mazzuchelli’s Batman: Year One—the project to which it seems meant to be a sequel in terms of look, tone, and time frame—it’s also astute enough to fairly accurately ape that feel in the first place. Even the occasional bizarre and wonky facial expression or disproportionate body harkens back to the primitive Golden Age artists of yore. If I were presented with Batman comics like this on a regular basis, unspectacular but entertaining and satisfying efforts akin to a good solid Law & Order episode, I would be a very happy Batfan indeed.

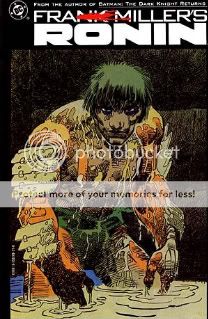

Comics Time: Ronin

April 25, 2008Ronin

Frank Miller, writer/artist

DC, 1984

302 pages

$19.99

If The Dark Knight Strikes Again is Frank Miller’s brain on SPX, I suppose Ronin is Frank Miller’s brain on Shogun Assassin. I’d say Lone Wolf and Cub proper or some other manga touchstone, but the thing is that my own comparative ignorance of Japanese comics and Miller’s enormous influence on Western ones make it hard for me to see evaluate this formally as anything but a Frank Miller Comic that happens to use samurai and Akira-style science fiction.

It’s a very good Frank Miller Comic in fact. Back then his art had this doodly/sketchy quality—lots of little loops and bubbles and curlicues—that had yet to solidify into the hyperrealist noir of the first Sin City chapters in Dark Horse Presents and thence to recede to the chunky bigfoot self-satire of DKSA or the later Sin City books. It’s a bold style, perfect for conveying enormity by expanding the blobby details to the edge of the page or isolating action by stripping them away and letting the remaining figures slash through them. It’s also beautifully colored by Miller’s now ex-collaborator Lynn Varley; no one has used greens this effectively before or since.

Storywise it combines the familiar Japanese pulp tropes mentioned above with the uniquely Millerian idiom of topless black bondage Nazi gangs (cf. The Dark Knight Returns, Sin City), evil corporations painted with an hilariously broad satirical brush (cf. Hard Boiled), and sinister omnipotent female computer programs (cf. Martha Washington–man, if in some future FM Batman comic the Batcomputer ever gets referred to as “she,” watch out). But moreso than in any Miller comics save perhaps his collaborations with David Mazzuchelli, there’s a refreshing space left for the human element. While there’s obviously a lot of “he is the Hero, he is everything” to be found here, much of the plot is driven by the comparatively quotidian doings of the Aquarius Complex’s worker bees: middle management, staff psychiatrists, laborers pissed off at the treatment of the fellow workers, an idealistic scientist and his security-guard girlfriend whose story of success-driven estrangement would fit nicely into a late-’90s period piece about a dot-com startup. So it’s easy to forgive some narrative lapses, like a jarring bit of told-not-shown infodumping about how the ronin entered the modern world whose raison d’etre only becomes apparent at the end of the story, and simply focus on the pleasures of the art and the tempered-gonzo writing. Capping it all off is a brancinglysudden ending and final image of triumph-through-simply-existing that I really wish more genre comics would ape. I will enjoy rereading this comic every four years or so until I die.

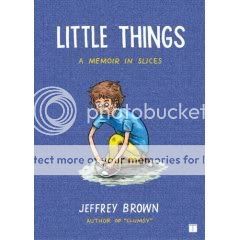

Comics Time: Little Things

April 23, 2008Little Things

Jeffrey Brown, writer/artist

Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, March 2008

352 pages

$14

It had been a while since I read a full-length Jeffrey Brown comic starring Jeffrey Brown, and I’d forgotten what a unique experience a Jeffrey Brown autobio page is. Reproduced at roughly the same size at which they’re drawn, Brown’s pages are almost always stuffed with six square panels, which are themselves crammed with penned detail. But despite containing so much visual information, the casual feel of Brown’s line and portraiture make the page come across more mellow than manic. Meanwhile, and particularly when compared to the many other sketchy (by design or necessity) slice-of-life efforts that have sprung up in Brown’s wake, his pop-eyed characters pop from their backgrounds, which themselves feel like fully realized and inhabitable spaces. The total effect is really accomplished and unique, and it turns out I missed it quite a bit.

This is the part of the review where I was gonna argue that in these ways the art mirrors the story, or nonstory, presented in the book itself: a sea of detail saved from unpleasant obsessiveness by a breezily directionless presentation, against which notable specifics stand out. This observation has the virtue of being true, but I feel like reading that much into what’s going on sort of defeats the purpose of the book. While Brown argues in his introduction that the point is that tiny, seemingly insignificant moments–coffee with friends, awkward movie-watching experiences–can take on the same importance as truly life-changing events–gall-bladder surgery, witnessing a horrific car crash, meeting the father of the mother of your child–to me the book ultimately demonstrates something slightly but vitally different: Those insignificant moments remain insignificant, yet occupy a disproportionately high rank in our mental catalog of memories, and the resulting stew of momentousness and meaninglessness is in the end what makes our lives what they are. Both are indispensable.

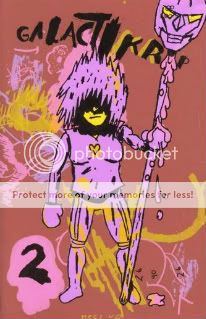

Comics Time: Galactikrap 2

April 21, 2008Galactikrap 2

Brian Chippendale, writer/artist

self-published, October 2007

72 pages

$8

This is what those “fun” superhero comics that nobody but predominantly superhero-comics bloggers reads would look like in an alternate universe where Gary Panter took over as Marvel house artist instead of John Romita Sr. and Los Bros Buscema following the departures of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. The major difference, of course, is where in those books the action-humor blend is the primary selling point, here it’s simply the tool Chippendale uses to set up the action beats and environments that are the meat of his cartooning. The yuks and fights are the means to an end, not an end in themselves, but they also happen to be really really crackerjack, which is more than you can say about this book’s Big Two brethren.

Plotwise, this is a follow-up to Chippendale’s earlier Battlestack Galacti-crap, a story of two tribes (cue Frankie Goes to Hollywood) of costumed weirdoes battling it out over the right to sell cupcakes in a particular area of their sci-fi city. It’s exactly as nonsensical as it sounds, which is totally fine because the point is the drawing, and man, it’s a pip. This issue kicks off with a brief silkscreend color section that evokes the full-color openings of manga volumes, a comparison subverted here by the supreme ridiculous of the subject matter (one of our warring tribes, Teamy Weamy, is debating whether to change their name to Team Tomb or Team Tummy). The rest of the comic comprises three separate, vaguely interlocking vignettes, each defined by the way they use sequences of panels to pace action. In the first (back at the cupcake stand from the first issue) a bug-laden “bugcake” is lobbed past a stunned onlooker at the head of a disgruntled customer; Chippendale draws the action out over several panels to call attention to its kinetic silliness. This is in contrast to the next big bit, in which panel after panel is left silent while two characters are placed on hold as they call a credit card company to find out why one of their cards has been denied–here the drawn-out sequencing conveys boredom rather than action. Things kick into high gear in the second section, which involves a pair of super-types infiltrating an underground lair and battling robot-type dudes. Chippendale’s chunky, crunchy line is a surprisingly effective canvas for action choreography, making the space in which the action takes place feel solidly constructed and lived-in while lending a certain palpable oomph to various ninja stealth antics, laser dodges, and one really memorable blast at a bad guy. the third and final sequence is mainly an excuse to create a convenience store shaped like Godzilla called Snackzilla, I guess, but it too has a laugh-out loud depiction of slapstick involving a bunch of characters getting bonked on the head with a baseball bat and sent tumbling down a hole in the floor by a secret member of a rival gang. After a funny, deadpan two-page bonus comic by Ben Jones about a dog who will become the Chosen One but at this point mostly stands around with his tongue lolling out, the comic ends with another two-page color section; as with the first issue, this finale displays Chippendale’s knack for drawing figures in freefall, but this time uses it to set up a funny gag about one falling character remembering he can fly mid-plummet.

The character designs are all funny and easy to parse–I sort of want to see these folks cross over with the gang from Powr Mastrs; the environments, particularly in a trio of stand-alone pages toward the end of the book, are immersive and mysterious; and since Chippendale is working with basically one or two large panels per page it’s probably a lot easier than Ninja or Maggots for your average civilian to follow. This is the kind of minicomic you’ll read from cover to cover each time you come across it wherever you keep your minicomics. If you spot this at a con you should buy it.

Comics Time: Forlorn Funnies #5: My Love Is Dead/Long Live My Love

April 18, 2008Forlorn Funnies #5: My Love Is Dead/Long Live My Love

Paul Hornschemeier, writer/artist

Absence of Ink, 2004

80 pages

$10.95

Buy it from Copacetic Comics still, maybe

Originally written on July 8th, 2004 for publication in The Comics Journal

The fifth installment of Paul Hornschemeier’s personal anthology series is a transitional work of sorts, a midway point between the publication of the author’s formidable graphic novel Mother, Come Home (the serialized installments of which completely took over Forlorn Funnies‘ previous three issues) and his upcoming entrée into the art-comix big time when Fantagraphics begins publishing the series. (This is the alternative comics equivalent of a WB starlet getting that phone call from Playboy–you’ve made it, baby!) Perhaps Hornschemeier himself sensed the in medias res nature of this project. It’s his most direct effort to date in forging a middle way between his satirical and melancholy modes. Granted, separating the two physically may seem an odd way of linking them, but the link isn’t any less clear for that.

As the book’s subtitle suggests, My Love Is Dead/Long Live My Love is indeed divided into two sections, one “funny,” one “forlorn,” each printed at a 180-degree rotation from the other. Each section has its own “front cover” featuring the appropriate half of the subtitle and a mood-specific image and color scheme (as well as, cleverly, the book’s bar code and ISBN information–this way there’s now way to guess which half Hornschemeier considers “the back of the book”). At the spread at the center of the book, where the two sections meet, we find two pages’ worth of rival “About the Author” material, one of which solemnly enumerates Hornschemeier’s C.V. and the other of which features a lengthy explanation for its use of the phrase “butt smear.” (You’re all bright people, so I’ll leave it up to you to guess which is which.)

Baroque conceits such as this are nothing new for Hornschemeier–you may recall that the entirety of Mother, Come Home is supposed to be the introduction to a novel of which we only see the first chapter’s title page. It’s fun to watch Hornschemeier at play in the fields of the formal, but what excites one most about FF5 are the cartoonist’s visual and storytelling skills, which continue to expand at an alarmingly brisk rate.

Perhaps the best example of this is the emergence, fully formed, of a vocabulary of the monstrous a la Woodring or Brinkman. These strange creatures and the psychedelia-by-way-of-graphic-design wilderness in which they live are used to great effect on both sides of the forlorn/funny equation. In the former case (“Underneath”), a furry, Yeti-like behemoth responds to his growling stomach by diving under the sea, assaulting one of the creatures he finds there, and devouring one of the creature’s young as its sibling and parent look on. The attacker arrives back on dry land only for its stomach to rumble yet again; he glances at the sea, and in the subsequent panel is nowhere to be found. The sequence is wordless, the creatures expressionless, but the horror inherent in the sea-creatures inability to protect itself or its children is palpable and chilling. As it trundles over to comfort its surviving offspring when the land-creature swims away, we wonder what it can possibly say to provide solace or safety; moreover, when we realize the land-creature has gone back underwater, we know that neither is in the offing. The humiliating powerlessness of parents in the face of overwhelming violence is usually the subject of only the finest literature (on TV, only The Sopranos goes there; in comics, you’re hard pressed to find explorations of the topic outside historical efforts like Maus and Safe Area Gorazde); it’s both jarring and inspiring to see this painful aspect of human existence broached in a monster comic.

On the funny side of things (“Ditty and the Pillow Plane”), the monsters are used (not surprisingly, as we’ll soon see) to explore similar themes. While the two title characters float along in a manner reminiscent of Mother‘s opening sequence, strange creatures bite each other, ride each other, attempt to devour each other, and run past the frame while on fire. Ditty (whose eyes are x’s) and the Pillow Plane (who has no eyes to speak of) grab a snack amidst the chaos, and the sequence concludes with this exchange: “Is civilization a cancer?” “Of the liver, Ditty.” This seems as accurate an assessment as any, given the absurd pandemonium going on around them.

The notion that something’s just sort of wrong with civilization and that we’ll never set it right is the funny side’s major preoccupation. This sentiment is frequently expressed in the broadest of terms–phrases like “Has it all been that senseless?” “Is it pointless to laugh?” “Fuck it all anyway!” and (especially) “Whatever, dude” echo one another from strip to strip. A trio of overt political cartoons help make this case as well. “Everyone Felt It” (its title emblazoned on a striking, stark black background) skewers the vague everybody-hurts semi-soul-searching the U.S. occasionally indulges in in times of tragedy. The star of “America, Your Boyfriend” is a MODOK-esque lunkhead who kicks the crap out of anyone who dares look askance at his SUV-driving, beer-swilling lifestyle. Personally, I believe that our country’s most devoted enemies, in their drive to quite literally revive the Middle Ages, have problems unrelated to our own nation’s admittedly troubling obsession with luxury vehicles, but the point is made clearly and, perhaps more importantly, hilariously. “The World Will Never Be the Same” depicts various people behaving like racist, sexist, xenophobic, elitist, patronizing assholes both “THEN” and “NOW,” 9/11 being the unspoken line of demarcation between the two. The strip is similar in effect to an oft-reproduced sequence from Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers, and if the simplicity of the message of both is a little disconcerting (gee, America still isn’t perfect? Bush lied!), Hornschemeier’s iteration is more effective both for the vicious specificity of its targets and his willingness to implicate himself with his send-up of patronizing artsy-fartsy types. (“Oh, absolutely, his work is really making a difference,” says one such gallery-attending schmuck as a presumably homeless man walks by.)

The excess of the artiste is another prime target. “Stupid Art Comics Are Stupid” is a gratifyingly reductive assault (at times, a physical one) on the pretensions of the modern artist, depicted alternately as a sex-obsessed phony or an empty-headed dilettante. Its follow up, an essay entitled “Stupid Art Comics May Be Stupid, But ‘Stupid Art Comics Are Stupid’ Is a Complete Waste of Time,” is written from the point of view of a critic enraged both by the earlier piece’s unsurprising “surprise” insights into the human condition and its creators insistence on designing it so that it can only be read if held upside-down in front of a mirror. A multi-page sequence entitled “Artist’s Catalogue” deploys a slew of anti-art gags, including several pages that are simply blank and a reprint of the meticulous, highly intellectual plans and sketches for what turns out to be an “I went down on your mother” joke. (Fans of a certain Mozart/Bach-inspired Spinal Tap song ought to be pleased.)

With Long Live My Love so fixated on depicting a world going to hell in a handbasket as society’s supposed coalmine canaries, the artists, jerk themselves off, it’s up to My Love Is Dead to make more personal, though equally universal, points. A strange, untitled sequence involving a man, his grandmother, and a blood orange is difficult to unravel–I’m still not exactly sure what’s going on, or more specifically what is about to go on–but the man’s sweat, tears, and self-contradictory statements speak volumes about the power and terror of family love. “We Were Not Made For This World,” a sci-fi parable about a robot seeking the source of its creation even as the desert through which he marches slowly erodes the automaton’s ability to continue, is reminiscent of any number of similar SF meditations on loneliness, from Martin Cendreda’s memorable minicomic Zurik Robot to Stephen King’s eerie short story “The Beach.” Hornschemeier’s skill with both art (depicting with mathematical precision the granules of sand that are inexorably eroding the robot from within) and words (“He focuses on the horizon and tries to think it is beautiful”), however, give the story its own tragic grandeur. Most impressively of all, in “These Trespassing Vehicles,” Hornschemeier uses a moment of random, catastrophic violence to center a story that encompasses the entire lives of its characters with daunting, heartbreaking totality. There’s even room for a thoughtful twist ending, itself emerging from a life’s irreversible turns. The story itself neatly mirrors the strength of Hornschemeier’s work in general. Some moments may overshoot, others may undershoot, but the ambition is always grand, and thanks to the keenness of the author/artists’s eye for detail amidst his expansive vision, so too is the execution.

Comics Time: Tales of Woodsman Pete

April 16, 2008Tales of Woodsman Pete

Lilli Carré, writer/artist

Top Shelf, May 2006

80 pages

$7

Was this a webcomic first? A series of microminis? I ask because the skill Lilli Carré shows in this anthology is so considerable in terms of its ability to build to a punchline that also doubles as an indictment of the specific brand of thoughtless waste she’s gunning for that it feels like you’re reading a best-of collection rather than a debut.

Tales consists of strips of varying length chronicling the comical misadventures of both the titular woodsman and the legendary tall-tale hero Paul Bunyan and his blue ox Babe. I’m not saying it’s a masterpiece–Carré occasionally gives into the temptation of a too easy joke, as in the first strip, where Woodsman Pete remarks upon the beauty of a pair of birds’ song and then kills them anyway; meanwhile many of her strips on Pete dealing with aging strike me as being a young person’s view of what old age is like; a lengthy section involving a future globally-warmed world where dried-up oceans leave great salt deposits behind never clicks as well as its length demands.

What I am saying is that it’s a remarkably assured book, one where even its weak spots (which strike me as less important the more I think about the collection) feel like deliberate choices rather than missteps. Carré’s thin, clear line, attractively presented in blue throughout, enables her to simultaneously cram many panels onto the book’s small pages–resulting in a bit-by-bit inch-by-inch dialogue pace that perfectly fits the stories’ shaggy-dog-tale rambliness–and give her characters an expressiveness that belies their knowingly crude design. I could sit and stare at Paul Bunyan’s hair and beard for minutes, while at certain points the shading on Pete’s hat and beard is almost tactile. The comparative realism of the animal heads mounted on Pete’s wall lends weight to what struck this particular vegetarian as a message of conservation buried beneath the black humor.

Meanwhile, the gags frequently arrive from unexpected directions. Along with his wall-mounted hunting trophies, Pete keeps row upon row of beard trimmings to mark the decades. A stuffed deer head presented as a flourish on the top of one strip is revealed to have a stuffed butt attached to it when we turn the page. When Pete calls one of his trophies his favorite, another one silently cries. In a strip called “Saturday Night,” Pete strips butt naked, dances around, then stops and falls asleep, and that’s the whole strip. It’s bracingly dry and cleverly delivered stuff.

The most impressive aspect of the collection is the unforeseen interlocking of the Pete and Paul Bunyan material. The giant lumberjack and his bovine friend don’t show up until about a third of the way through the book; when we realize what’s going on and that the images that kick off his arrival seem tied directly to the events of the preceding Pete strip, it’s a rewarding little epiphany. However, Carré fudges the details of the strips so that it’s never quite clear whether or not Pete and Paul are actually anywhere near each other temporally or spatially, which besides being a fairly complex narrative conceit for a gag-strip collection speaks directly to the larger point she’s making about the unreliable nature of memory and storytelling and the dubious prospect that these mental phenomena can actually enable true and lasting connections between different people. All this for seven bucks? Sold.

Comics Time: Mattie & Dodi

April 14, 2008Mattie & Dodi

Eleanor Davis, writer/artist

self-published, 2006

40 pages

$5

Buy it from Little House when its shop re-opens in June

This one didn’t quite do it for me. Partially I think it’s because Davis’s relatively realist story this time around, about a working-class woman who’s forced to take care of her elderly, bed-ridden grandfather and her very young and withdrawn little sister, lacks a certain level of mystery compared to the fables and fantasies I’m more familiar with from her. The problem is that Davis tries to apply some of the same storytelling techniques here that she uses in her fantasy stories–mysteriously silent characters, long wordless stretches, a touch of the monstrous (in the form of the moaning grandfather), matter-of-fact nudity–and they end up overwhelming any sense that this is real life carefully observed. (She isn’t helped by the hard-to-swallow obliviousness with which she imbues her main character.) Her cartooning is as strong as ever, with dynamic figures and an at times stunning selection of body language for her characters, but an overuse of zip-a-tone, strangely inorganic lettering and slightly over-animated facial expressions push it just a bit into slickness. It’s funny, I remember reading in Gary Groth’s interview with Davis in Mome that this was the comic that really made him sit up and take notice, but for me it feels like a detour from the more fruitful avenues of expression she’s pursued before and since.

Comics Time: Wet Moon Book 1: Feeble Wanderings

April 11, 2008Wet Moon Book 1: Feeble Wanderings

Ross Campbell, writer/artist

Oni Press, December 2004

172 pages

$14.95

I’d imagine your tolerance for this book will vary proportionately to your tolerance for goth culture, because it’s definitely about goths. There are a lot of piercings and unusual hairstyles and ripped stockings and purses with little batwings sewn on them. But this strange, slow story about a group of kids at either the Savannah College of Art and Design or a fictional facsimile thereof isn’t your usual po-faced every-day-is-Halloween goth artifact. There’s a sadness and a weakness and a feebleness to everyone’s presentation of themselves as Goths, a recognition that this identity is the result of chipping away at certain surface characteristics until the desired result is achieved but that there can still be any number of chinks in the armor. Cleo and her friends/enemies more or less live in squalor, with pizza boxes and bags of chips and cockroaches strewn hither and yon. They make much of their bodily functions. They always look kind of tired and sickly. None of this is in the glamorous way that goths are supposed to work, either. Indeed the only character who truly appears to have perfected a seamless goth look and lifestyle is treated almost like an alien. And humor deflates the pretension on several occasions (what’s up, punch to the boobs?).

What is glamorous about the book is its recreation of that sense of languid, sexy ennui-bordering-on-mania that afflicts certain types of people in college. Laziness so profound it becomes almost sensual, a constant unspoken sizing-up of your fellow young people as sexual objects, a feeling that, despite being surrounded by like-minded individuals in a setting expressly designed to stimulate the exchange of ideas, you’re alone with your thoughts. This is essentially the storyline, but it’s best expressed through Campbell’s art itself. His women are extremely sexy in the way his lush line sort of idealizes their imperfections, and his dudes ain’t so shabby either, but they all have this slightly slackjawed, tired-eyed look of being dazed. Campbell frequently frames them awkwardly within their panels, using the surrounding space to suggest that they’re always a little lost, which is sort of the point.

Comics Time: Jessica Farm Vol. 1

April 9, 2008Jessica Farm Vol. 1

Josh Simmons, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, April 2008

100 pages

$14.95

It’s a truism to say that comics have an unlimited special effects budget, thus casting their unfettered nature with regards to other narrative arts like film and television as primarily rooted in spectacle. But that sky’s-the-limit difference can be a formal one as well. With few if any physical or logistical constraints on an ongoing creator-owned comic’s length–particularly during this Internet Age–the ways in which stories are told may be similarly stretched. Any artist with a preexisting propensity for rambling, discursive narratives will find this limitlessness to be right in their wheelhouse.

No one seems to be stepping up to this plate with more determination than Josh Simmons, the underground-informed cartoonist behind many gleefully vulgar minis and anthology contributions who really exploded into comics-cognoscenti consciousness with his relentlessly bleak, wordless survival-horror graphic novel House last year. Jessica Farm Vol. 1 is the initial fruition of a project he’s apparently had simmering for eight years, a projected 600-page graphic novel drawn one page per month and released in 96-page installments every eight years until its completion in the year 2050. With Jessica Farm, Simmons has created a comics-reading experience where getting there isn’t half the fun–it is, by definition and at least for the next half-century or so, all the fun.

Is it fun? The answer is a qualified yes. For starters, Simmons tackles the erotic far more directly than any other cartoonists of his generation that I can think of, excepting Hans Rickheit I suppose–certainly more directly than anyone else with his Fantagraphics-granted level of exposure. The parts of this volume I’ll remember most vividly involve the titular teen (?) grabbing other male characters by the cock on more than one occasion, an earthy and erotically matter-of-fact gesture. While character design does not strike me as Simmons’s strong suit, he does give Jessica a winsome jolie-laide beauty, with wide eyes and sensually ropy tresses. And he really tapdances along the line that separates sexy from smutty from potty-humor in his depiction of his characters’ bodies. When we catch a glimpse of Jessica’s pudenda sticking out slightly from between her legs as we see her shower from behind, or when the mute, naked Mr. Sugarcock seasons her soup by dipping his balls in it Louie-from-The-State-style, or when Sugarcock’s full-tilt sprinting is indicated by his namesake member flopping like a windsock in the opposite direction, the sight is intimate, titillating and discomfiting all at once.

Indeed Simmons excels as an artist of human physicality. Fans of his memorably gruesome Batman pastiche will no doubt be delighted to find that comic’s thoughtful illustration of the body at work echoed throughout Jessica Farm, from watching tiny little people clamber up stairs that are each twice their height to the many shots of Jessica diving or pole-sliding through the many floors of her seemingly enchanted home. Depicting the cavernous and claustrophic contours of that home and other environments by moving his characters through them is another great strength of Simmons’s cartooning, and the scenes in which Jessica and her alternately adorable and threatening companions wend their way through the house’s darkened corridors no doubt contain within them the seeds of House, the artist’s full-length exploration of exploring.

The problem with this experiment, I suppose, is one of its methodology. The attention-getting publishing schedule is no doubt what made you aware of the book in the first place, and in terms of sounding completely awesome, hey, mission accomplished. But once you hit page 96 and realize that it’ll be another eight years before a subsequent volume provides you with a continuation–and more importantly, a context for–what you’ve just read, the bloom fades off that rose in a hurry. As I was getting at before, the format lends itself perfectly to a peripatetic story in which Jessica, Alice- (or Odysseus)-like, has a variety of surreal encounters. But as Alan Moore once astutely pointed out, myths need a Ragnarok, and without the hard defining line of an ending (at least until the grandchildren of the Bushes and Clintons are running for office), there’s no real way to judge whether Jessica’s rambling, discursive adventures are more or less than the sum of their dream-logic parts. So for every powerful image, like the Paperhouse-esque silhouette/villain/father or the little French band that plays in Jessica’s shower, there’s something that seems a bit on the nose without further explanation or exploration, like the cute li’l monkey getting stabbed to death or a room full of giant fetus-babies with their eyes gouged out and tongues pulled out. Without the constant an ending would provide, the equation is unsolvable. Of course, we wouldn’t even be discussing these challenging topics if the comic were not an experiment to begin with.

Comics Time: Tekkon Kinkreet: Black and White

April 7, 2008Tekkon Kinkreet: Black and White

Taiyo Matsumoto, writer/artist

Lillian Olsen, translator

Viz, September 2007

624 pages

$29.95

Perhaps the most fascinating thing about Taiyo Matsumoto’s Tekkon Kinkreet is how its art constantly draws attention to its nature as art yet never compromises the totality of the story’s vision. Like a Gahan Wilson cartoon or Klaus Voorman’s cover for the Beatles’ Revolver, Matsumoto’s shaky—I almost wanna say gawky—line reveals itself as the product of a hand committing ink to paper on every page. Its largely uniform weight draws the eye to every detail at once, momentarily disabling the part of our brain that tricks us into seeing comics pages as three-dimensional environments rather than an assemblage of flat shapes, at least until Matusmoto’s skillful spotting of blacks (holy moses, check out page 538!) once again guides us back into the illusion.

Step back for a wider view and the gangly linework fits neatly with the spindly, frequently scarred characters, and the messy city they inhabit, most often viewed from the ground up like a lost child would see it. There’s a weakness to the art that is again reinforced by the story: On a certain level it’s a futuristic, dystopian crime-action thriller about rival factions (cops, street gangs, yakuza, a sinister religious/entertainment corporation, and two feral kids named Black and White) battling for control of a sprawling city called Treasure Town. But while the action is thrilling–and, refreshingly enough for a translated manga with a potentially byzantine plot, easy to follow–where the book really hits home is on an emotional level. Its elegiac feel is perhaps meant to recall real-world analogues like the Disneyfication of New York City, but for me it functions as a message about caring for people and things who are past caring for themselves. It’s defined by relationships between people who end up making themselves emotionally vulnerable and yoked to a belief in something better at great risk to themselves–streetwise Black’s love for his idiot-savant brother White, White’s love for his increasingly brutal brother Black, crimelord the Rat’s desire to preserve the city he’s mostly just stolen from, the cops’ desire to preserve even the criminal underclass against an encroaching and even more vicious modernity. Now, as someone who’s gotten a lot more enjoyment out of Disneyfied Times Square than Taxi Driver Times Square, many of the book’s more didactic moments and gangster poses fall flat with me. But there’s a part of everyone that still pines for wild youth, warts and all.

In the end almost all the characters are forced to choose the things that are most important to them and move on, leaving the rest behind, which is essentially how the process of growing up works. It’s a coming of age tale that actually feels like coming of age does. I’m really impressed by how slowly and naturally these themes unfold, too–Matsumoto has a grasp on pacing that makes this serialized work read just great in a collected edition. It’s all packed into a well-designed, hefty softcover, the kind of book that begs to be given as a gift or passed from reader to reader. Recommended.

Comics Time: Planetes Vols. 1-3

April 4, 2008Planetes Vols. 1-3

Makoto Yukimura, writer/artist

Yuki Nakamura, translator

Anna Wenger, adapter

Tokyopop, 2003-2004

Volume 1: 240 pages

Volume 2: 268 pages

Volume 3: 240 pages

$9.99 each

Originally written on July 1st, 2004 for publication in The Comics Journal

The unending torrent of translated manga titles is all too easy for a reader raised on American comics to drown in. Unfamiliar and therefore arbitrary-seeming conventions, countless -makis, -muras, and other seemingly interchangeable surnames, and that damned right-to-left flow: It’s enough to cause Western eyes to glaze over. It’s gotten to the point where an exasperated sigh of “I just don’t get manga” is viewed as an acceptable assessment in some circles. Indeed, “It’s all speed-lined, Japanophilic crap starring giant robots and big-titted doe-eyed schoolgirls in their panties” has assumed a place of (dis)honor right along side “It’s all mindless, sexist, crypto-fascist adolescent power fantasies about men in tights hitting each other” (mainstream/superhero/genre comics) and “It’s all pointless, self-obsessed, navel-gazing slice-of-life stories about pathetic white guys feeling sorry for themselves” (alternative/underground/art comics) in the pantheon of stupidly dismissive sequential-art stereotypes.

Enter Makoto Yukimura’s Planetes, the antidote to conventional wisdom about what translated manga can be, and the perfect gateway drug for fans of American art- and genre-comics alike. Compelling characters, story, and art add up to one of the finest regularly published titles you’re likely to come across on the racks today, from any country.

Working within the type of hard science-fiction framework not often seen in genre comics, Planetes takes place in the semi-near future, a time when orbital space stations bustle with civilian activity, the moon has been colonized, Mars is on its way to being so, and a manned expedition to Jupiter is on the horizon. The high volume of space travel has given rise to unforeseen, space-borne growth industries, the least glamorous of which is debris pick-up. Glorified garbagemen travel through low Earth orbit, picking up busted satellites, wreckage from shuttle accidents, discarded refuse, and other space junk before it can collide at high velocity with unwary travelers.

From this SF premise, writer/artist Makoto Yukimura (ably assisted by the nearly invisible adaptation work of Anna Wenger) spins something pretty close to magic. The key–and it’s so simple it’ll make you kind of angry that every writer doesn’t employ it–is that the action stems not from the external dictates of plotting or the need to get across some “mad idea” aimed at knocking the metaphysical socks off the reader, but springs organically from the internal workings of the characters themselves. And what characters they are.

We’re first introduced to Yuri, an astronaut of Russian decent, in a full-color flashback, on board a passenger space flight with his wife. Even this very first scene is peppered with the alarmingly perceptive moments that make the series so memorable: Yuri’s wife carries a compass with her every time she travels through space, in order to remember that even in the directionless void, there’s a direction home. It’s the sort of short, sharp shock of instant insight and attachment that makes the ensuing, slow-motion catastrophe all the more wrenching to watch, as does Yakimura’s jarring change in perspective from an extreme, speed-blurred close-up to a cold, impersonal long shot. The accident that claims Yuri’s wife’s life was caused by the type of debris storm that Yuri, in his new career as a debris clearer, seeks to prevent, though his stoicism is complete enough to hide this true, tragic motivation even from himself.

Yuri’s crewmate Fee is a much less quiet sort. A chain-smoking American woman of the sort some space-age Guess Who might sing about, Fee is the Bones McCoy of the hauler’s crew. Her deadpan, take-no-shit refusal to indulge the melancholy reveries of her shipmmates makes her not just a natural foil for the sensitive Yuri and the moody Hachimaki (crew member number three), but a literal lifesaver given the mental duress contact with the vastness of space can engender. As if to contrast Fee’s level-headedness with the space-shot flakiness of the other main characters, Yakimura assigns her the series’ single most heroic act–preventing the destruction by terrorists of an entire space station, which in turn would generate enough debris to effectively end space travel for years. Fee’s heroism, however, derives not from some high-minded belief that man is meant for the stars, but from a jones for the cigarettes available for sale on the space station. It’s not idealism that motivates Fee–it’s a nic fit.

The aforementioned Hachimaki initially strikes the reader as the book’s shallowest, least-interesting character. Hachimaki may be a garbageman, but his ambition to be something more is clear. It’s alternately expressed as a desire to own his own spaceship (a luxury item even in this era of lunar cities) and an obsession with becoming a crew member on the first, years-long manned trip to Jupiter. By now readers familiar with the conventions of manga characterization may be rolling their eyes: The young man who works relentlessly to become the best in his chosen field is a staple of shonen stories, from your standard martial-arts adventures to the culinary competitors of Iron Wok Jan. And of course, you don’t need to be a manga devotee to know that The Brash, Tow-Headed Rookie With Something To Prove is a well-trod road indeed.

But as Hachimaki moves to the forefront, eventually becoming the lead character of the later volumes, we’re stunned to see the emergence of a genuinely complex and conflicted character. There’s nothing conventional at all about Hachimaki’s near-pathological desire to prove his emotionless self-sufficience to anyone who cares to notice. The emptiness of space–which in one of Volume One’s most harrowing sequences nearly cripples the still-inexperienced astronaut–is both the perfect nemesis for him to conquer and the perfect refuge in which he can hide from the emotional demands of interpersonal contact. It’s this that Hachimaki finds more frightening than the risks of space travel, in which humans are after all little more than glorified debris themselves.

Yukimura’s ability to slowly coax out the emotional core of his lead character lies not just in his expertise in shaping Hachimaki himself, but in the gorgeous sensitivity with which he peppers the story with memorable supporting players who naturally elicit moving and riveting responses from the upstart astronaut. There’s Mr. Rowland, the aging astronaut who’d rather abandon himself to the ravages of the lunar desert than die Earthside. There’s Nono, the lunar-born girl whose emotional strength exceeds that of her low-G-weakened physiology. There’s Hachimaki’s family: His father, the head-in-the-clouds veteran astronaut; his brother, the cool, single-minded amateur rocket scientist (seriously); his mother, whose love for her family is constantly tested by their passion for being thousands of miles away from home. There’s Hakimu, the anti-colonization terrorist (the other big growth industry of the era) whose initial refusal to kill Hachimaki is more devastating to the young explorer than his eventual change of heart. There’s Sally, the captain of Hackimaki’s Jupiter-bound crew whose last-ditch attempt to snap him out of his malaise is equal parts touching, hilarious, and (well) hot. Last and certainly not least there’s Tanabe, Hachimaki’s successor aboard the debris hauler and the woman whose belief in a thing called love becomes more attractive to Hachimaki the more infuriatingly naïve he finds it.

But the real miracle of Planetes is that its indelible characters are matched by unforgettable imagery. “Visual poetry” is how I’ve heard it described, and that nails it as well as any description can. Yukimura’s style is already more realistic and appealing than many of his counterparts’, but he adds to this an almost uncanny ability to produce both individual moments and entire sequences of stunning visual impact. Volume Three’s finest moments come when a white cat, embodying Hachimaki’s conflicting desires for death and love, directly addresses the viewer (in place of Hachimaki himself), its white tail coiling and swaying against the black void so vividly as to be nearly animate. Volume Two offers another demonstration of Yukimura’s skill with contrast: As Hachimaki nearly drowns following a motorcycle accident back on Earth, he’s drawn as a reverse negative–fluid, minimalist white lines against a black background. The effect, amidst Yukimura’s rich realism and almost colorful graytone, is as startling as the accident itself. And it’s not just extreme mental states that Yukimura evokes with panache: His splash pages of lunar landscapes and extraterrestrial vistas immediately bring to mind the vivid, alien beauty of Kubrick’s 2001, or the powerful contrast between man and nature of a Ford or Leone. Meanwhile his simple character work is just as memorable. Two standout moments come from Volume Three: Tanabe grinning as the wind blows through both her hair and the beautiful array of windmills behind her, and Tanabe’s father on stage during his punk-rock filth-and-fury heyday. The last time I saw the heart-rending loveliness of a happy, beautiful woman and the super-fuckin’-funness of rock and roll depicted this convincingly, I was reading Love and Rockets.

Is that a fair comparison to make? I think it just might be. Literate comics fans have, I think, been conditioned to ignore the kinds of books put out by the American manga-publishing giants like Tokyopop and Viz; they’ve convinced themselves to stick with the Tezukas and Miyazakis and Tsuges, or to pine wistfully after a vaguely defined glut of Good Stuff They’re Never Gonna Translate. But do yourself a favor. Elbow your way past the TRL-watching kids lined up in front of the manga racks at the bookstore. It’s an unlikely place to renew your faith in comics, I know, but if you pick up the sturdy, gray-spined volumes of Planetes you find there, that’s exactly what this emotional, beautiful series will do.

Comics Time: Incredible Hercules #114-115

April 2, 2008Incredible Hercules #114-115

Greg Pak & Fred Van Lente, writers

Khoi Pham, artist

Marvel Comics, February & March 2008

22 pages of story each, I think?

$2.99 each