Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

Comics Time: The Best of the Spirit

December 31, 2008The Best of the Spirit

Will Eisner, writer/artist

DC Comics, 2005

192 pages

$14.95

Will Eisner’s The Spirit is a virtual symphony of dudes getting socked in the head. I think that’s what I ultimately took away from my read of this best-of collection of 22 Spirit 7-pagers, assembled by persons unknown using criteria unknown. No matter how far Eisner stretches the parameters of his strip; no matter if it’s the masked vigilante/bounty hunter’s origin story, or a standalone tale about an ill-fated criminal or plastic toy tommy gun in which the Spirit happens to show up on the final spread; no matter if it’s a surprisingly psychologically astute portrait of a soldier who loses it after coming home from the war or society girl whose depression leads her to take up with criminals and then commit suicide-by-shootout, or a whacked-out EC riff about a killer granny with images and dialogue as crazy as anything Frank Miller could possibly put on screen–no matter what, somebody, somewhere, somehow, is gonna get clocked on the noggin.

That all but universal action beat, and the presence of the nattily attired Spirit himself, give you a throughline as you watch Eisner and his studio’s style evolve from the barely recognizable 1940 origin story to the trademark caricature, pantomime, and big-city atmospherics of the 1950 capstone strips. By the end, Eisner’s Gene Kelly-esque action choreography is at the height of its unique, humorous appeal; it tickles me to observe how naturally he’d apply the same play-to-the-balcony techniques he used for slobberknockers and machine-gun massacres to the body language of his late-period melodramas a couple-three decades hence.

I came into this collection expecting one dominant Spirit storytelling mode to emerge, one style to prove self-evidently definitive. But based on this sampling, the Spirit really could be all things to all funnybook fans: harsh or poignant, stark or silly, realistic or far out, surprisingly rich or divertingly slight, Humphrey Bogart or Tex Avery, a Hero or a Maguffin. Eisner’s experiments with form only reinforce the natural diversity of his subject matter. Everyone’s entitled to their Spirit. Me, I’ll go with the one that entails the most people getting cold-cocked.

This is my final comics review for 2008. Thank you for spending Comics Time with me this year! -Sean

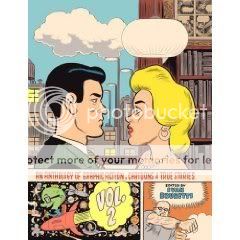

Comics Time: Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!

December 29, 2008Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!

Art Spiegelman, writer/artist

Pantheon, 2008

72 pages, hardcover

$27.50

I wonder if Art Spiegelman really believed it when he wrote this:

Although Breakdowns figures prominently in my life and my development as an artist, I was still startled when Pantheon expressed interest in re-issuing the book. I couldn’t help but worry that, once the scarcity factor was removed, Pantheon would be lucky to sell as many copies as the 1978 edition.

The print run of that edition: approx. 2,500 usable copies.

I wonder if he believes this, too:

Arteests get to be shamans; us cartoonists are mere “communicators.” As Chris Ware succinctly put it years later: “When you don’t understand a painting, you assume you’re stupid. When you don’t understand a comic strip, you assume the cartoonist is stupid.”

I wonder because that same Art Spiegleman is the guy who wrote this:

[The young Art Spiegelman] was on fire, alienated and ignored, but arrogantly certain that his book would be a central artifact in the history of Modernism. Disinterest on the part of most readers and other cartoonists only convinced him he was onto something new in the world. In an underground comix scene that prided itself on breaking taboos, he was breaking the one taboo left standing: he dared to call himself an artist and call his medium an art form.

While the hard-won pages the self-important squirt gathered in Breakdowns were among the first maps that led to comics being welcomed into today’s bookstores, libraries, museums and universities, he wasn’t making a conscious bid for cultural respectability.

And this:

The discoveries I made while working on the strips in that book have somehow been absorbed by those interested in stretching the boundaries of comics over the past thirty years, even if only second or third hand.

Well, if you do say so yourself, Mr. Spiegelman!The thing is, it’s the Spiegelman of the latter two quotes who has history on his side. It’s entirely possible he really does possess a Ware-like self-esteem problem, but whereas Mr. Acme Novelty Library’s vicious self-deprecation is seemingly seamless and never-ending, Spiegelman alternates his “aw shucks who the hell’s gonna buy the best-of collection from the little old Pulitzer Prize winner” routine with bold–and largely substantiatable–claims about his work’s iconoclasm and import, and with impassioned defenses of its merit and his high opinion thereof.

It’s this collision of opposite levels of confidence even more so than Spiegelman’s oft-discussed High Art/Low Art dichotomy that characterizes this new edition of Breakdowns. Why else surround a re-release of his long out-of-print collection of experimental comics–really ground zero for “alternative comics” as we know them today–with a sizable autobiographical comics prologue (the “Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!” of the title) and a lengthy prose afterword detailing his entire comics career through Breakdowns‘ initial publication? It’s as though today’s post-Maus, post-Pulitzer, post-New Yorker, post-9/11 Spiegelman can see that the early, seminal works of an artist of his stature deserve a high-end forum for public consumption, yet can’t quite bring himself to provide it without appending at least as many pages again of “wait–I can explain!”

I’m all for that explanation, by the way. Spiegelman’s a cartoonist whose biography is a familiar one–the seismic influence of MAD, emerging in the work of him and his underground comix contemporaries and passed on to another generation years later through his work on Wacky Packages and Garbage Pail Kids; his involvement with the undergrounds, his growing dissatisfaction with their emphasis on the shocking and scatalogical, and his efforts to carve out a space for comics as art/literature; and of course his parents’ suffering in the Holocaust, his mother’s suicide, and his at times crippling survivor’s guilt. But it’s enlightening to hear it all straight from the horse’s mouth, whether through the somewhat discursive comic memoir that kicks the book off or the linear who what when where why and hows of the prose afterword. His father’s frugality (and ignorance of prevailing beliefs regarding comics and juvenile delinquency) ends up leaving little Art in the possession of stacks of bargain-bought EC Comics instead of the more staid funnybooks he’d previously been exposed to. The rise of his friend R. Crumb convinces young Spiegelman that comics are in good enough hands for him to tune in, turn on, and drop out for a couple of years, culminating in a trip to the psychiatric hospital. Seeing his housemate Justin Green work on Binky Brown inspires him to ditch the fantastical outrages of the undergrounds for the based-on-a-true-story horrors of his first “Maus” strip. His girlfriend’s matter-of-fact self-defense during an argument–“I didn’t do anything!”–leads Spiegelman to realize he’s actually angry at his late mother, and thus produce his breakthrough comic, “Prisoner on the Hell Planet.” As a person whose own involvement with comics is owed just as much to a series of right-place-right-time coincidences and connections, it was fascinatingly familiar even when I was learning the details for the first time.

But what of the comics themselves? The original Breakdowns material is yet another illustration of Spiegelman’s warring tendencies. In some, he aims to make “art comics” by aping High Art styles–“Hell Planet”‘s Expressionism, “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore”‘s Cubism-cum-Art Deco, “Ace Hole: Midget Detective”‘s Picasso femme fatale. (Can you beat Pablo’s portraiture as a visual metaphor for “two-faced”?) In others, Modernist painting schools don’t enter into it, as he unapologetically guns for comics themselves, smashing them apart to see what makes them tick and rearranging them as he sees fit–“Nervous Rex: The Malpractice Suite”‘s non sequitur visual and dialogue sampling and splicing; “Day at the Circuit”‘s choose-your-own-moebius-strip panel layout; “Little Signs of Passion”‘s self-reflexive use of color, deferred-gratification sequencing, and distracting snippets of pornography; “Zip-a-Tunes” and the front and back covers’ monkeying with zipatone and color separations. Spiegelman jumps back and forth between attempting to demonstrate his place in the tradition and using form to display a disinterest or even antipathy for tradition, focusing instead on pulling apart the pieces of his chosen medium and angrily stitching them back together. I suppose that itself is a tradition, especially in 20th century art (and Spiegelman never quite peels himself away from his pissing match with the museums), but in comics it even now reads like a revelation.

It looks nice, too. Perhaps the biggest impact this volume will have is settling the question of whether Art Spiegelman can draw. That is a question, right? I’ve certainly heard emperor/clothes kvetching about Maus‘s cramped black-and-white panels and ugly figurework (as though those sorts of things never occurred to him when he was trying to determine how best to visually represent the Shoah). Maybe it’s those children’s books he’s done in the interim, but I found the comics in the prologue to be adorable little things, with an inviting color scheme of sky blue and cantaloupe orange and endearing caricatures of his parents. (Seeing the stars of Maus drawn as cute middle-aged human beings was unexpectedly poignant for me.) Meanwhile, the chops displayed in a variety of styles in the Breakdowns material, from underground-standard riffs on funny animals and old-time strips to those High Art pastiches to his experimental zeal with layout to a really rather breathtakingly bold choice of colors (especially for the time) are argument-enders. Dude could draw the hell out of a blowjob, by the way.

You don’t have to be a Pulitzer Prize winner to figure out that the title Breakdowns was selected by Spiegelman in 1978 for its double meaning. After all, about half the comics in the original collection dealt with Spiegelman’s personal and psychological traumas, while the other involved taking the unexamined stuff of a popular art form and, yep, breaking it down. Thirty years later, it feels even more apt. By now, Spiegelman’s had a chance to freak out over the success of the very kind of comics his work helped make possible–a breakdown over the breakdown, if you will. Indeed, you can’t help but wish he’d continued producing work of the caliber of Breakdowns‘ better pieces on a regular basis throughout all this time, instead of rather infamously backing away from it for years following Maus‘s smash success. You walk away from Breakdowns hoping he’ll pull himself together in time to continue pulling things apart.

Comics Time: Planetary Book 3: Leaving the 20th Century

December 26, 2008Planetary Book 3: Leaving the 20th Century

Warren Ellis, writer

John Cassaday, artist

DC/WildStorm, 2005

144 pages

$14.99

Originally written on October 23, 2005 for publication by The Comics Journal. I was an angrier person back then.

THE DUDE: How’s the smut business, Jackie?

JACKIE TREEHORN: I wouldn’t know, Dude. I deal in publishing, entertainment, political advocacy–

THE DUDE: Which one’s Logjammin’?

–Joel and Ethan Coen, The Big Lebowski

Warren Ellis wants you to take him seriously. I don’t. Partially it’s because he, the man who coined the term “pervert suits” to refer to superhero costumes, has heaped as much scorn on supercomics as the day is long, and noisily stormed away from the genre in a rage to try his hand at the wave of the future he dubbed “pop comics,” has spent most of his career as a Comics Superstar writing thinly veiled Super Friends fanfiction and is currently the author of Ultimate Fantastic Four, Iron Man, the “Ultimate Galactus” trilogy (!) and JLA: Classified. Partially it’s because this supposed anti-establishmentarian could not write a comic that didn’t feature a select group of badass illuminated übermenschen using their secret knowledge of the world to shape it into a better one for the good of the sheeplike plebes from whom this knowledge must be kept at all costs if his life depended on it. And partially it’s because his mobile-podcast-Delphi-forum digital-revolutionary comics-activist persona, his relentless touting of (say) Godspeed You Black Emperor! accompanied by diatribes about how (say) Avril Lavigne is bullshit, his name-dropping of his fetish-model friends and his close pal “Bill” Gibson, and his desire to utilize the Internet to cultivate groups of people who think and act exactly like he does coupled with his willingness to rage against the Internet when it cultivates groups of people who do not all remind me too much of an over-earnest black-clad Newcastle Brown Ale-drinking college sophomore who writes record reviews for the campus daily while not busy reading up on the connection between Terrence McKenna and the Rosicrucians at Disinformation.com. (I know this–because I was that college sophomore!!!)

But mostly, I guess, it’s the superhero thing. I feel for Ellis because he’s so obviously conflicted in his feelings about that which Siegel & Shuster and Lee & Kirby hath wrought. How else to explain the cognitive dissonance of his Jan. 8, 2005 “Streaming” column for the comics news website The Pulse, in which he dismissively proclaims the following:

“I think possibly [excellence] is measured in how something grabs at you, how it makes you feel, what it does to your brain, what it says to you. For some people, yeah, that’s going to be all about what’s in Green Lantern’s underpants or whatever, and that’s okay. Personally, I look for the Rock And Roll and the Manic Pop Thrill elsewhere. My point, if I have one at all, is that this year the majors are focussed [sic] on each other, and on making millions off the handful of old characters we already know. There are no surprises to be had out of “mainstream” DC and Marvel in the coming year. Which means it’s down to the rest of the medium to provide them.

This, of course, while Ellis was busy accepting Avi Arad’s dirty American dollars for rejiggering armored avenger Iron Man (he used to use repulsor rays–now he’s into the societally transformative power of cellphone technology!), armored dictator Dr. Doom (he used to rule an Eastern European nation with an iron fist–now he’s rules a commune of hipsters in Amsterdam with mind-controlling cyber-tattoos!), and godlike planet-eater Galactus (he used to be a big huge guy in a purple helmet–now he’s a virus-like swarm that’s the living embodiment of the Fermi Paradox! And oh, he’s called Gah Lak Tus now, because that’s less ridiculous somehow!).

The point, I suppose, is that people who developed a coterie of camgirl acolytes by shitting all over superhero comics probably shouldn’t write them without expecting to be hoist by their own petard, and not coincidentally creating some of the dullest freaking superhero comics in the history of forever. (Thank goodness Marvel has only managed to actually release two issues of Ellis’s Iron Man, as I think that’s about as much technophilic tedium anyone could take before pulling a Unabomber.) At the very least, such people should develop a much deeper cover for their closeted compulsion to write stories about metahuman do-gooders blowing things up with their awesomeness. And that, in a nutshell, is what Ellis has done in Planetary, the title that like as not is what enables people to refer to him in the same breath as an Alan Moore or a Grant Morrison without involuntarily giggling.

Planetary concerns a trio of superpowered individuals–a temperature-controlling albino named Elijah Snow (get it?), a superstrong/superfast/supertough PVC enthusiast named Jakita Wagner, and a long-haired technopath named the Drummer–who flit about the world investigating various bits of pop- and pulp-culture fictional ephemera that, it turns out, happen to constitute the world’s real “secret history.” Basically, there really is a Godzilla, a Doc Savage, an Incredible Shinking Man (a blacklisted Communist sympathizer subjected to cruel experimentation by the United States government, naturally)–it’s a bit like the plot of Return of the Living Dead, in other words–and it’s up to our trio of “mystery archaeologists” (to use the pretentiously juxtaposed job description assigned them by Ellis) to use this knowledge for good, or something.

Their primary opponents in this quest are the Four, a team of enormously powerful metahumans who rule the world and just happen to be badass what-if versions of the Fantastic Four. In many ways they resemble the titular superteam from another Ellis creation, The Authority, who are a team of enormously powerful metahumans who rule the world and just happen to be badass what-if versions of the Justice League, except that the Four are bad guys and the Authority are good guys. Now Ellis, that lovable scamp, has been known to claim that the Authority are the villains of their comic, but to paraphrase Harrison Ford, “You can say this shit, Warren, but you sure can’t type it”; you’d have to be a mystery archaeologist to unearth evidence of the Authority’s villainy from the text itself, which reads like a prolonged MASH note to the group’s hyperviolent Lefterventionism. (Shit, man, you wanna read a genuine critique of the superheroes-take-over idea, read Mark Gruenwald’s Squadron Supreme.) Regardless, that the man who’s derided supercomics as a go-nowhere culture of remixes has created at least two comics that revolve around Fatboy Slim dance versions of Big Two teams says more about Ellis than his inescapable “what I’m listening to/what I’m reading” lists, despite his efforts to portray things to the contrary.

Planetary has a couple of things going for it–neither of which is its endless recycled riffery on superior genre entertainment. “Hey, it’s the Hulk–only DEADLIER!” “Hey, it’s a John Woo movie–only WEIRDER!” “Hey, it’s Sherlock Holmes–only he’s the leader of the ILLUMINATI and he’s brought DRACULA as his MUSCLE!” “Hey, it’s Tarzan, only he FUCKS MONKEYS!”–you’ve now experienced the majesty of Ellis’s condescending chop-shop work on stuff he’s too embarrassed to straight-up enjoy. Perhaps the nadir of this tendency is the issue in which a troupe of Vertigo-character analogues appear and are rejected as the hopelessly dated relics of their Thatcherian era–after which Ellis’s Vertigo character, Transmetropolitan‘s Spider Jerusalem, shows up and is duly crowned the trail-blazing heir to Gaiman, Moore et al. In other words, pretty much everything sucks–until Ellis puts his stamp on it, at which point it’s the tits. This is morally and aesthetically superior to milking “The Death of Gwen Stacy” for thirty years how, exactly?

But everything’s drawn beautifully, which is Planetary‘s first virtue. Artist John Cassaday can get a little lazy with the backgrounds, but his figure work is astonishing (no pun intended, X-fans!), all warm curves shot from fascinating angles. He’s an excellent choreographer of action (see Chapter 16’s wire-fu homage) and a prodigious talent when it comes to conveying Ellis’s admittedly sharp pacing choices (as in the the silent five-panel sequence where the team’s attempt to infiltrate the Four’s headquarters is discovered and thwarted with literally earth-shaking violence). Cassaday’s go-to colorist Laura Martin is every bit as compelling here. Avoiding both the vomit-like palette of greenish browns that mars much of DC’s “serious” output and the Skittle-explosion Photoshop slop of the big guns, her sensible and sensual colors perfectly fill out the contours of Cassaday’s pencils. Her monochromatic work is always a sight to behold–like her contemporary Dave Stewart, she can do more with one color than most colorists can do with, well, all of them.

Virtue number two is a structural one. Earlier volumes of Planetary were interesting for the way Ellis bypassed the traditional climactic slugfest of superherodom for an approach that genuinely mirrored that of (yep) archaeology. More often than not, Snow, Wagner, and Drums would show up after the action took place–investigating gargantuan radioactive lizard corpses on Monster Island, watching a spectral flashback to a Hong Kong cop wrongly slain, and so forth. As Ellis’s subconscious yearning to write Secret Wars took over this tactic was mostly abandoned, but it’s been replaced by what may end up being the most drawn-out prelude to a final confrontation between protagonists and villains in superhero comics history. Each issue contains a small step forward or push backward for the Planetary team’s quest to thwart the Four, who are so powerful that they’re nearly omnipotent and therefore require a whole lot of planning and effort to thwart. Volume Three culminates with the team’s first successful mano-a-mano with a member of the Four (the Human Torch knockoff)–it’s taken eighteen issues for them to take out their adversaries’ weakest link. Ellis craftily builds the Four into such a formidable obstacle that we’re more than willing to follow the Planetary crew’s long and winding road for the sense that they’ll surmount that obstacle in the end.

It’d be nice if our drivers on that road were at all interesting, though, and that’s ultimately Planetary‘s fatal flaw. Swap the color schemes and the sex organs and you’d be hard pressed to spot the difference between main characters Elijah Snow and Jakita Wagner at all. Consisting of virtually nothing but the type of deadpan “I’m incredibly blasé about this outrageously cool thing that I’m looking at”isms that Ellis has somehow made a career out of, their dialogue is completely interchangeable; indeed, one of the few non-Cassaday pleasures to be had from Volume Three is the flashback sequence from back when Snow still spoke in a Claremontian down-home American dialect, since if there’s any other way in which Snow is different from Wagner–or Apollo, the Midnighter, Jack Hawksmoor, Jenny Sparks, etc etc etc–I’d love to hear about it. (I’m reasonably sure Spider Jerusalem smoked more, but of course tracking the number of times Ellis added “substance abuser” to “ubercompetent badass” and called it a personality would require a whole ‘nother essay.) Ellis characters are little more than dim echoes of things that made other characters interesting, wrapped in skin, adorned with a superpower and a kewl outfit, and pushed on-panel to kill a few hundred thousand people, kick someone in the junk, and recite whatever Ellis read on Metafilter that day.

They’re just superheroes with a slightly better iTunes playlist. One with lots of podcast subscriptions, no doubt. Sigh. Warren, call it “Galactus” and be done with it, already.

Comics Time: The Other Side

December 24, 2008The Other Side #1-2

Jason Aaron, writer

Cameron Stewart, artist

DC/Vertigo, 2005

32 pages each

$2.99 each

Originally written on November 22, 2006 for publication by The Comics Journal. I went in for vitriol back then.

Agent Orange and The Other Side might seem different on the surface, in that the former is a chemical defoliant used during the Vietnam War and the latter is a comic book about the Vietnam War. But look a little deeper and you’ll find that they have two important characteristics in common: They both led to the destruction of trees, and they are both fucking awful.

No shopworn Vietnam shibboleth goes un-beaten-into-the-ground by writer Jason Aaron, who uses an apparent real-life friendship with author Gustav Halford, whose book The Short Timers was adapted into Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, as an excuse to pilfer every last sample-ready soundbyte from that film, strip it of context, and fire it like a Deer Hunter Russian-roulette bullet directly at the reader’s brain, with predictably hideous results. Nearly every line of dialogue seems to consist solely clichés strung together like a necklace of human ears: “IF YOU ARE NOT SQUARED AWAY AND BORN-AGAIN-HARD…THE GOOK WILL FUCK YOU UP BEYOND ALL RECOGNITION!” Complementing this one-dimensional portrayal of the American fighting man as an obscenity-spewing kill-crazy redneck motivated alternately by bloodthirsty chauvinism, pants-shitting terror and batshit insanity is the depiction of the Vietnamese everysoldier as a pristine holy warrior who talks like a cross between Mao and the Mandarin. The series’ parallel structure only highlights the unintentional hilarity of the characterizations. I couldn’t possibly illustrate this more clearly than by simply transcribing issue two, page one—which is split into two panels depicting the two main characters and their fellow soldiers—in its entirety:

[LEFT]

NARRATOR: The Twelfth Lunar Month in the Year of the Sheep. Vietnam. Somewhere between the coastal city of Vinh and the Laotian border. Deep within the holy sanctuary of the rain forest, we begin our historic journey with a cheer.

LEAD SOLDIER: For the liberation of our compatriots, the defense of our families, the defeat of our oppressors and the reunification of our fatherland…

ALL: Let’s march south!

[RIGHT]

NARRATOR: December 1967. Vietnam. Quan Nam province. Chest deep in the stinking mud of Danang, I begin my tour of duty digging holes for men to die in.

SOLDIER 1: Welcome to the exotic Indochinese Peninsula, new guy. Where heroes die young, and assholes live forever.

SOLDIER 2: Where dinks don’t die, they just go to hell and regroup.

SOLDIER 3: You think it sucks now? Just wait ’til you’re wasted.

SOLDIER 4: Whoopee, we’re all gonna die.

Can you guess which side is which? Holy Christ, it makes that scene from Platoon where the guy shows Charlie Sheen the picture of his sweetheart back home look inspired. Even poor Cameron Stewart gets fragged: His poppy, buoyant art has been a treat in semi-revisionist superbooks like Catwoman, SeaGuy and The Manhattan Guardian, but here his figurework goes from solid to stolid to squalid, losing all sense of movement and stripping the battle scenes (massacres all, naturally) of any power to grip, excite or terrify, not that they’d have much of a shot at doing so as written anyway. What was that quote from Full Metal Jacket again? Oh yeah: “I am in a world of shit.”

Comics Time: The Mystery of Woolverine Woo-Bait

December 22, 2008The Mystery of Woolverine Woo-Bait

Joe Coleman, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, December 2004

40 pages

$4.95

We serial-killer buffs are an odd lot. I think there are different ways people come to a fascination with famous multiple murderers, but one of the most common and influential in terms of the resulting art and pop/junk/cult culture artifacts is to see them as a real-world extension of Famous Monsters of Filmland. When you’ve cycled through the Universal monsters, the Hammer horrors, the BEMs and giant irradiated monsters of ’50s science fiction, Vampira and Zacherle and the creature-feature hosts, “collecting” knowledge about ghoulish characters like Ed Gein and Albert Fish can seem like the next logical step. I think you also see the earlier serial killers–Fish, Gein, Richard Speck, Albert De Salvo, Carl Panzram, right up through Charles Whitman (technically a mass murderer, or spree killer depending on how you look at it) and Charles Manson–were and are presented in much the same way that horror movies were to children of the ’50s and ’60s, as an antidote to rules and parents and conformity. The dark side of the American dream and all that.

I’m not coming to serial killers like that. Maybe I did once; not anymore. Joe Coleman, on the other hand, is the patron saint of that approach. A trash-culture outsider-art icon, his paintings treat serial killers like medieval saints, surrounding them with the facts of their often horrendous upbringings and even more awful crimes. Woolverine Woo-Bait, originally released in 1982 and here combined with a six-page continuation that actually came out five years earlier, is sort of the comics embodiment of his aesthetic. Serial killers themselves play only a small, inspirational role, representing the “conception of the psychological make-up required to survive or mutate in the post-atomic era,” but in addition to their cameos, you’ve got the aliens from Mars Attacks, acromegalic character actor Rondo Hatton, an entire old-school freak show, mad scientists, zombie Holocaust victims, crazed square-jawed soldiers, Ed Wood repertory players Vampira and Tor Johnson, rape, disembowelment, cannibalism, a woman with two functioning sets of male genitalia where her breasts should be, Jo Jo the wolf boy…if you spent some portion of the ’90s on a David Lynch/John Waters/psychobilly-inspired sojourn through the rotten edges of post-War American culture, you’ll know what you’re in for. Coleman draws it all like a man possessed, placing his panels against backdrops and borders of schizophrenic detail. The plot is negligible–suffice it to say people do disgusting, violent, perverse, and occasionally breathtakingly racist and anti-Semitic things to one another; the point is to uncontrollably vomit all this junk back in everyone’s faces. There’s a part of me that will always have an affinity for this kind of thing, that will always enjoy being on the outside. There’s another part that stands there and says “Well, here we are, we’re Outside…now what?” Are violence and suffering holy, as Coleman argues? Or is it that they’re important to expose, that ripping off the scab like this comic does has a value to it, but there’s something unspeakably sad underneath and a failure to acknowledge or address it is an American dream of its own?

Comics Time: Capacity

December 19, 2008Capacity

Theo Ellsworth, writer/artist

Secret Acres, October 2008

336 pages

$15

Beautiful, magical, complex, and possessed of the irresistible, quiet confidence of those for whom making art is less a choice than a given, Capacity impressed and delighted me as much as any book this year, and as much as any debut since the first issues of Skyscrapers of the Midwest. In Theo Ellsworth’s constantly unfolding details and army of mysterious, dreamlike characters, you will see the fantastical echoes of artists like William Blake, Hieronymus Bosch, Clive Barker, and Marc Bell. But before you picture a nonsensical riot of whimsy and/or grotesquerie, dig the comic’s conceit: Ellsworth, represented here by several characters that correspond with different aspects of his mind, invites you the reader (whom he directly addresses with a recurring fill-in-the-blank ______ slot where your name is supposed to go) to join him as he walks you through a sort of artistic autobiography, in which he both presents you with the contents of the minicomics and abandoned projects he’s done over the years and provides them with context. It’s an enormously endearing set-up, one that never drifts into preciousness even when the comics in question feature ultra-earnest doggerel poems about the horror of war or the nature of thought.

As a title, Capacity really does do the trick. Aside from the fact that the book is itself a braindump of as much of Ellsworth’s comics as he could fit, Ellsworth’s knockout art style is characterized by its…I want to use the word “prolixity” but that’s pejorative. Basically, scaly reptiles or dragons will seemingly have thousands of individually drawn scaled. Feathered ogres or furry monsters will have countless feathers or tufts of fur. A man surrounded by little creatures will wear clothing and hats that consist of villages of houses that contain other people and creatures who have their own house-clothing that contain other people and creatures, and so on and so on. It’s filled to capacity, in other words, but not in the crazed, violent manner of your Joe Colemans and Bald Eagles, or even the goofball non sequitur chaos of the aforementioned Marc Bell–here, the ripeness and rifeness of the imagery is inviting, immersive, evocative of environments you want to enter and explore. That’s a central trope of Ellsworth’s own relationship with his ideas, which he seems to regard as independent entities. Such is his deadpan sincerity on that point that an idea that can seem laughable or pretentious when proposed by other artists here just makes you go “well, certainly.”

By the end of the book, I was so engrossed by the uniqueness of Ellsworth’s project and the skill of its execution that I never even really thought about how potentially disjointed such a book could seem in less assured hands. But not only does it all flow rather seamlessly, there’s a final-pages reveal/twist that cleverly and delightfully links together long-abandoned story strands to uncover a throughline that was there all along. It’s a wildly successful little story-as-puzzle moment, like a great Grant Morrison comic or David Lynch film. It makes you want to go back and re-read the whole thing, not “to see what you missed” or anything but just because it would be fun and rewarding to do so. I have a feeling this will be a book I’m diving into every now and then for a long time to come.

Comics Time: American Splendor: The Life and Times of Harvey Pekar

December 17, 2008American Splendor: The Life and Times of Harvey Pekar

Harvey Pekar, writer

Kevin Brown, Gregory Budgett, Sean Carroll, Sue Cavey, R. Crumb, Gary Dumm, Val Mayerik, Gerry Shamray, artists

Ballantine Books, August 2003

320 pages

$15.95

I find myself a bit stymied in trying to figure out how to kick off this review, since this material has already been digested and processed by so many people. I guess I’ll go with talking about R. Crumb’s art here. Obviously it’s the strongest of Pekar’s collaborators–I know, shocker, right? Indeed I’m a little surprised he could persuade other artists to take a crack at it. Befriending the foundational artist of alternative comics back before he was famous, becoming inspired to do comics in the first place because of that friendship, and then finagling a series of collaborations out of him–that’s the most auspicious comics career kick-off this side of Marc Silvestri and Michael Turner getting paying work out of their first ever comic-con visits. But while it’s easy to see that Crumb’s technique is superior to the other cartoony guys in the book, and that his more impressionistic approach is somehow more visually stimulating and rewarding than the photorealists, I liked his character designs the best. Crumb draws Harvey and his friends and coworkers like tiny little guys out of a fairy-tale world, only with collared shirts. Pekar is a slightly hunched-over, wild-eyed ogre or hermit, his pal Mr. Boats is a roly-poly sage or scribe of some kind–that kind of thing. No? But the caricatures lose none of the nuance needed to convey Pekar’s little insights and pet peeves regarding the workaday modern world. There’s a beautifully accurate bit of body language at one point where Crumb is listening to his visiting friend while leaning against a file cabinet, and the sneer shared by those two women in that strip where the guy tries to sell them okra cracked me up.

I suppose it’s details like that that I enjoyed the most, not just in the art, but in the writing. Pekar’s penchant for describing his life’s most mundane details in what you’d imagine to be a voice just a few decibels louder than comfortable conversational level is what provides these stories with the energy they need to keep from being soul-crushingly dull, but that energy doesn’t overwhelm his capacity for keen observations. For instance, there’s this passage from a strip about how Harvey’s failed second marriage actually taught him that he could, in fact, be happy given the right circumstances:

Yeah, I got what I thought I needed and it turned out it really was what I needed. What a wonderful feeling! It’s like, y’know, when you’re not used to building stuff, like you’re not mechanically inclined, and you put something together from instructions in a book and you think you’ve done it right, but still you have no confidence. So then you turn it on and it works. Boy, what a rush!

Folks, you should have seen how thrilled I was when I managed to properly install my TiVo on the very first try! I knew exactly what Pekar meant, and that thrill of recognition was another LOL moment for me.

I think that’s what I take away from this collection: It’s kinda cute! Pekar’s an irascible guy, obviously, with no shortage of qualities that might make him tough to take in real life, but there’s something about his extravagantly straight-faced presentation of himself that’s comical and adorable. Yeah, a lot of the art is stiff or unprofessional, and yeah, a lot of the stories end like one of Brak’s Tales of Suspense, but when faced with life’s vicissitudes, a storytelling approach that acknowledges how they can weigh on you but still makes them look slightly ridiculous strikes me as being a pretty healthy one.

Comics Time: I Shall Destroy All the Civlized Planets

December 15, 2008I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets!

Fletcher Hanks, writer/artist

Paul Karasik, editor, afterword writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

124 pages

$19.95

Okay, so obviously the thing that strikes you initially is that these stories are completely insane. They treat the basic structure of superhero comics–“villain commits crime, hero captures villain,” as Karasik’s mother puts it in the afterword–like the bare necessities for a spirited game of Calvinball–all you need is Calvin, Hobbes, and a ball, and the rest is up to your imagination. And Fletcher Hanks’s imagination was twisted beyond description. It’s not just that the demises his godlike heroes Stardust and Fantomah cook up for their villainous prey are brutal, it’s that they’re needlessly baroque. So Stardust doesn’t just feed a racketeer to a giant golden octopus–He wraps up the bad guy in his giant flexible hand, whisks him away to a desert island that he first overwhelms with a tidal wave, then lifts up into the air, drops the guy onto, flips over, and puts back down, after which the guy is flushed through an underground lagoon onto the shore, and then and only then does the golden octopus eat him. Similarly, Fantomah doesn’t just toss a ring of diamond thieves to a pit of cobras–she whisks them away to the jungle pit of death, where she fuses them into one person, who is terrified by the creatures of an unfound world, flees up a mountain only to find a dead end, gets scared off the cliff by a giant floating paw, and gets caught by a whirlwind that blows him into a cave filled with giant albino cobras who kill him, after which Fantomah floats his body out into midair, where the unfound world creatures summon another disembodied hand from the cliff surface to grab it and drag it back into the cliff, where it presumably remains to this day. The picture of Hanks as a naive dispense of two-fisted justice doesn’t do justice to these comics at all. They have a stream of consciousness feel to them that makes Final Crisis seem straightforward and restrained. They’re more than just goofy and violent and mean, though they’re certainly all of those things–they’re unrestrained, unhinged.

But even more than that, they’re things of great beauty! I can’t stress that enough. Hanks may have been a lot of things, but he truly was a wonderful visual stylist. A favorite tactic involves suspending his various thugs, heroes, corpses, jungle creatures, weapons of mass destruction etc. in mid-air, an effect that is dynamic and still at the same time, suggestive of great power and great restraint simultaneously. There’s a lovely panel of multicolored planes dropping matching bombs, another of a red sky filled with the floating silhouettes of giant panthers. Indeed, any time Hanks gets to draw a lot of the same thing at once is a good time to be a comics reader. That aforementioned albino cobra pit, an army of giant disembodied flaming pink claws–they’re almost always beautifully arranged within their panels and dazzling in their multiplicity, a signature effect as recognizable as Kirby krackle or Ditko hands. Hanks wasn’t a perfect cartoonist by any stretch–anatomy, obviously, was not his strong suit, and it’s those goofy underbites and mircrocephalic heads that give him his Ed Wood rep–but what he did well, he really did well.

Comics Time: Maggots

December 12, 2008Maggots

Brian Chippendale, writer/artist

PictureBox, 2007

344 pages

$21.95

Buy it from PictureBox, pretty cheap in fact

Here’s a hard one to wrap your head around. Maggots is a book that almost prides itself on its insular incomprehensibility. Originally and infamously drawn over the pages of a Japanese book catalog, its panels are meant to be read in a chutes-and-ladders zig-zag that skips, stutters, and shifts direction entirely the second you finally feel like you have a handle on it. In a sense, the first effect you get from reading the book is to learn how to read it. Slowly, your eyes become better at detecting characters’ changes in direction, their movements up or down, how they sit down or stand up or lie down, how they eat or fuck or simply walk up to one another. Eventually these clues enable you to read enough panels in the proper order–or at the very least get some kind of overall sense of what’s happening on a page–so that you can understand what’s going on.

So what’s going on? Well, that’d be kind of difficult to grok even if the book weren’t constructed like a clue someone found in the Orchid Station on Lost. Basically, a bunch of little munchkiny guys run around (literally, a lot of the time) behaving in ways that frequently lead to violent confrontation, whether that involves giants, or rabbits with samurai swords, or people stealing each other’s eyeballs, or the victims of eyeball theft coming back to exact their revenge. The “story” isn’t so much a plot as it is a sense of ever-present danger, the idea that the cute li’l business we’re seeing involving eating raisins and sticking the container somewhere hard for someone else to get to afterwards could at any moment give way to a legion of attacking mice, or some sort of death-mask-wearing sorcerer, or some genuinely unpleasant knifework.

The tension is maintained by Chippendale’s art, which feels like a peak into a hermetically sealed limbo of endless black, occasionally interrupted by secret trapdoors, ladders, and at least one food stand. Panels are tiny, cramped, filled in as much as they can be, careening wildly from one end of the page to the other. Even the white space is busy, showing the text of the catalog underneath. No matter how much our hero Hot Potato and his comrades and enemies run, jump, climb, crawl, and even fly, there doesn’t seem to be any way out for them. Of course, this makes the moments when Chippendale pulls back for a dazzling spread–a field of flowers, the arrival of that sorcerer guy, a massive staircase–all the more impressive. That’s the oldest trick in the book, but there’s a reason for that: It works.

And so, in its weird way, does Maggots. This isn’t going to be launching a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle-style wave of imitators anytime soon, even among the most Fort Thunder influenced cats around today–a 344-page experiment in graphic novel form? It’s a miracle this thing ever got published. And it’s certainly a challenging, at times frustrating read, with not a whole lot in terms of immediate satisfaction going for it. But once you get into that groove of letting your eyes weave back and forth across the pages, you just start appreciating the aesthetic qualities of the thing. Those chunky black panels. Chippendale’s Muybridge-like proficiency with breaking physical action down into its constituent beats. The character designs. The humor (“We have a no pants, no service policy.” “Do you have pants back there? I’ll take them.” “Sorry–no pants, no service”). The genuine, if raw, eroticism of all those bizarre sex scenes (I actually think this strange, avant garde comic captures the awkwardness and explosiveness of long-distance relationship reunions as well as any I’ve read). The random, astutely observed moments of quotidian business (there’s a great, two or three panel bit where Hot Potato scoops up a cat who was crawling around the sink that brought a smile of familiarity to my face). Even the sumptuous texture of the cover underneath the dust jacket. This is not a comic for everyone, duh, but if you’ve been interested in it in the past, I think you’ll find it interesting.

Comics Time: Real Stuff

December 10, 2008Real Stuff

Dennis P. Eichhorn, writer

∆, Rick Altergott, Peter Bagge, Jim Blanchard, Ariel Bordeaux, Rupert Bottenberg, Chester Brown, Ivan Brunetti, Charles Burns, Howard Chackowicz, David Chelsea, Dan Clowes, David Collier, Dave Cooper, Robert L. Crabb, Lloyd Dangle, Julie Doucet, Michael Dougan, Gary Dumm, B.N. Duncan, Gene Fama, Mary Fleener, Drew Friedman, Renée French, Roberta Gregory, Sam Henderson, Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, Sean M. Hurley, Gerald Jablonski, Peter Kuper, Carol Lay, Jason Lutes, Kent Myers, Bernard Edward Mireault, Carel Moiseiwitsch, Terry Moore, Pat Moriarity, Joe Sacco, Seth, Leslie Sternbergh, Carol Swain, Holly Tuttle, Colin Upton, J.R. Williams, Jim Woodring, Joe Zabel, Mark Zingarelli, artists

Swifty Morales Press, 2004

208 pages

$19.95

Buy it used, and cheap, from Amazon.com

How is Denny Eichhorn not a major cult figure? I’m honestly curious, and maybe some of my older readers can fill me in, since obviously he was a big deal in ’90s altcomix culture. But I can’t remember ever discussing him or his work with any of my friends or peers; the few times I’ve brought him up in the context of being one of three writers who’s made a go of creating alternative comics without drawing them himself, alongside Alan Moore and Harvey Pekar, I’ve gotten funny looks. Heck, I didn’t even really know what I was talking about, not until I read this collection. And shit the bed, I sort of feel like I need to physically pass it around to all of my friends until they’re all on my wavelength. To quote The Big Lebowski, “I won’t say ‘a hero,’ ’cause what’s a hero?”–but Denny Eichhorn is a goddamn inspiration.

I think the great trick of this collection of some of Eichhorn’s sex/drugs/violence-soaked autobio strips–drawn by the above host of collaborators, all of whom seem perfectly at home with their material, which is really a testament to them and Eichhorn both–is editor and publisher Caleb Wright’s chronological arrangement of them. That way, we get to know Eichhorn as a child first, and by the time his most outré misadventures head our way, it’s too late to detach ourselves from him. So sure, it’s funny to watch Peter Bagge draw Eichhorn getting so freaked out by his first Mad magazine he pukes, or Pat Moriarty showing a mix-up at a pharmacy that leads to young Denny being sold a pack of condoms for a science project, or early-vintage Dave Cooper (already a dazzlingly slick illustrator) presenting the story of how the cops broke the crazy next-door neighbor’s dick free of the glass bottle it was struck in. (There will be blood.) Even in the first serious bouts of violence we see, teen- and college-age Eichhorn is in the right; when a double-page Joe Zabel/Gary Dumm spread shows us exactly what happens when Eichhorn smashes a glass bottle into the face of his attacker, or J.R. Williams shows the toe of Eichhorn’s boot literally splattered with the remains of his assailant’s eyeball, you almost can’t help but cheer even as you recoil, laugh with triumph even as you shake your head with disbelief. It’s like the autobiographical comics equivalent of the climax of Rambo.

So when you finally start seeing hints of how Eichhorn’s tendency toward illicit behavior can bring out the worst in other people, and vice versa, it becomes a lot harder to write him off. Yes, there’s a way of looking at things where tipping off the part-time prostitute who’s hosted a week-long gangbang of the entire freshman class of Eichhorn’s university that the cops were on to her was the right thing to do–but this more or less ensured a continued life of abusive neglect for the baby she plies with cola and calls “Shithead” when she’s not fingercuffing the football team. There’s no reason to believe that the string of sex workers with whom Eichhorn has off-the-books dalliances are anything but the carefree lust-for-life types they (and Eichhorn!) appear to be–until one turns out to be the accomplice of a pair of serial sex murderers (and a serial killer in her own right), and another sticks a gun in her mouth and pulls the trigger mere hours after sticking Denny’s cock in her mouth and pulling his. That last strip may contain the most memorable cartooning in the entire anthology, which is really saying something amid the Saccos and Colliers and Chelseas and Woodrings and Doucets: Carel Moiseiwitsch’s deep blacks and deranged linework evoke Rory Hayes as the soon-to-be-suicidal woman literally attacks Eichhorn’s genitals, and caps things off with the post-orgasmic entreaty “REMEMBER ME!”–no narrative caption set-up, no establishing shots, just the woman’s demonic face.

This is not to say that it’s all eye-gouging and self-destruction. A lot of Eichhorn’s doping, drinking, and fucking are perfectly delightful for everyone involved, and a lot more are embarrassing but hella funny in hindsight. You’ve gotta love a book that includes a story about a dominatrix that ends with the sentence “Then it hit me: I shoulda pissed on his head!” and whose genuine, if off-kilter, father-son bonding strip involves giving your dad weed. It’s the gestalt of the thing that makes it so memorable, and enough to put you off comics about the awkward night Brooklyn Hipster had that one time forever. It fits right in with Boy’s Club, the Manly Movie Mamajamas, and other vicarious portraits of the less savory side of masculinity pushed to its illogical conclusion. If I could get 20 copies of this I’d give them away as stocking stuffers.

Comics Time: Kramers Ergot 6

December 8, 2008Kramers Ergot 6

Sammy Harkham, editor

Alvin Buenaventura, assistant editor

Carlos Gonzales, Shary Boyle, Matthew Thurber, Jason T. Miles, Andrew J. Wright, Sammy Harkham, Fabio Viscogliosi, C.F., Dan Zettwoch, Mark Smeets, Marc Bell, Bald Eagles, Chris C. Cilla, Martin Cendreda, Paper Rad, Jerry Moriarty, Gary Panter, Suihô Tagawa, Vanessa Davis, Souther Salazar, James McShane, Shary Boyle, Jeff Ladouceur, Ron Regé Jr., Elvis Studio (Helge Reumann & Xavier Robel), Tom Gauld, John Porcellino, writers/artists

Chris Ware, Tim Hensley, Paul Karasik, contributors

Buenaventura Press/Avodah Books, 2006

336 pages

$34.95

Can I just say how much I love how this volume of Sammy Harkham’s landmark anthology series opens? Credits pages in big, no-nonsense, all-caps letters alternate with splash page pin-ups and blown-up panels from the strips to come. It’s like the book has an opening credit sequence. I coincidentally paged through it at the same time as listening to “Speed of Life,” the opening track on David Bowie’s album Low, and it was as delightful a comics-reading experience as I’ve had all year.

That said, this may be the least immediately impactful post-volume-four Kramers. In some ways that’s to be expected: The previous volumes, particularly 4, were so groundbreaking that at a certain point you kind of just have to stand there and say “wow, we’re standing on the ground we broke a while ago, how about that?” As a matter of fact, I think this is the farthest-out volume, least “alt,” most “art/underground” collection of the three–there’s a degree to which it takes for granted that you’re willing to slug it out there on the borderland between comics and fine art and tugs you deep into the realm of the non-narrative and non sequitur.

For the most part, that’s a fine decision. There’s rough stuff to ponder from Bald Eagles, whose self-pitying, society excoriating autobio strip is transformed into something of a sci-fi fantasia by art so maniacally detailed it makes Geof Darrow look like John Porcellino, and from Chris Cilla, who serves up a sordid, coprophilia-tinged story of undercover cops gone very very bad. There’s stunning color work to be found in the rainbow psychedelia of Shary Boyle’s series of disturbingly sexualized 18th-century illustration riffs, in the green-on-pink shimmerings of Matthew Thurber’s goofball saga of a high school overtaken by a Mayan human-sacrifice cult, and in the lush pastels of World War II-era manga-ka Suihô Tagawa’s deceptively adorable funny-animal war propaganda. There’s the de rigeur contribution from the reliably hilarious Paper Rad, a literal interpretation of “Kramer’s Ergot” that made this Seinfeld fan laugh out loud. Competing takes on minimalism–C.F.’s explosively dynamic sci-fantasy and John Porcellino’s suburban haiku–bookend the collection. This is all exciting work, bursting with visual vitality and a certain distaste for the rules. It’s mostly loud and it’ll get you funny looks when you read it on the train (trust me), but it’s also very intelligent, rarely if ever shock for shock’s sake.

However, I do feel like there’s a higher quotient of work here that doesn’t quite, uh, work. I’ve seen enough of the oft-anthologized donkey strips of Fabio Viscogliosi and Fervler & Razzle strips of Souther Salazar to last me for quite some time. Bald Eagles and Jason T. Miles aside, most of the autobio work here–from James McShane, Vanessa Davis, and Ron Regé Jr.–works any better here than it does in the other anthologies you might have seen it in lately. Marc Bell’s stream-of-consciousness illustration/text combos just make me wish he was making more of his hysterically funny, rewardingly weird comic strips instead. I think the formal strength of Gary Panter’s Dal Tokyo strips reprinted here is diluted somewhat by being surrounded by so much similar material, so much illogic’n’markmaking. On the flipside, the more straightforward strips–Tom Gauld’s latest “two lonely coworkers in a weird environment” strip, Harkham’s tale of discontent in the shtetl, an emo little thing from Martin Cendreda, another story of mild hijinks in a midwestern church that occasionally uses diagrams from Dan Zettwoch–feel drowned out by the visual cacophony of your Bells and Elvis Studios and the monumental fine-art splash pages of your Boyles and Jerry Moriartys.

But I tend to be quite forgiving to anthologies that serve up a selection of inconsistent but thrilling-at-its-best work, and in that sense Kramers Ergot 6 is no exception. Indeed, the entire Kramers project seems to me to be one of juxtaposition, a when-worlds-collide affair. Not all those worlds are going to be equally interesting, but that’s fine when the ones that are are so rich and rewarding of your comics-thinking time and attention.

Comics Time: My Brain Is Hanging Upside Down

December 5, 2008My Brain Is Hanging Upside Down

David Heatley, writer/artist

Pantheon, September 2008

128 pages, hardcover

$24.95

The prospect of reviewing these intensely autobiographical comics by David Heatley is a daunting one because there seems to be no way to do so without reviewing David Heatley. Oddly, I’ve never really felt that way about his work before when I’ve encountered it. I thought his surreal “Overpeck” serial in MOME was powerful–as good as his dream comics might have been had he not labeled them “dream comics” and thus neutered their disquieting illogic. I’m also on the record as a great admirer of his “Sex History” strip as it appeared in Kramers Ergot 5 (the 48-panel grids were a brilliant way to convey such an overwhelming amount of uncomfortable information), and a defender of the “Portrait of My Mom” and “Portrait of My Dad” strips that appeared in Ivan Brunetti’s second Anthology of Graphic Fiction (they displayed Heatley’s underappreciated sense of humor and comedic build-up within each sub-strip). In none of these cases did I feel like I was evaluating Heatley as a person.

But My Brain put me in that uncomfortable position, perhaps–almost certainly, in fact–because my reaction to it was so viscerally negative. There are plenty of comics I’ve read that left me thinking “that should have been done differently”; this is the first I’ve read in a long time that made me think “this shouldn’t have been done at all” (and wasn’t written by Jeph Loeb). The primary culprit? “Race History,” a black-and-white (no pun intended) companion piece to “Sex History,” detailing Heatley’s relationships, however slight, with various black people he’s known. I’m trying to think of how to put this…there’s probably a way to take this idea and not make it just as dehumanizing and racist as it seems it would be, just as dehumanizing and racist as the behavior and mentality one assumes it’s designed to expose and excoriate, but boy howdy did Heatley not find that way! There’s something almost literally nauseating in this interminable onslaught of alternating bigotry and white liberal guilt. The point where my disgust for the strip became insurmountable was a scene where young David is sleeping over at a friend’s house, and the kid’s mother helps take care of David’s stomachache. “Try laying on yo belly. It should settle yo stomach down,” she says, in dialect reminiscent of late-’70s Marvel Comics street toughs, before David thinks “I forgot she’s a doctor.” And blam! It struck me how disgraceful it is to take this human being, who has a family, who worked the crazy hours and racked up the crazy student loans and god knows what else that all doctors do, reduced to a “blackcent”-spouting cameo in some guy’s ungodly long (seriously, at one point I closed the book and saw how many more black-trimmed pages of the strip I had left and my draw literally dropped) narcissistic display of how he’s spent his entire life looking at black people as being black before people.

I think the grossest thing about the strip, the part that prevents me from saying “well, he’s just cataloguing his own faults, he’s aware of how awful this is” is that even when his relationships with black people are healthy, mutually enjoyable ones, Heatley still seems to view them as trophies to prove his enlightenment. Every positive interaction with a stranger, every move to a black neighborhood that goes well, every friendship, every professor who helped him–it’s all the same as when he joined the Free Mumia movement, or the truly insufferable album (and sometimes movie/tv) reviews peppered throughout the strip where he proves how able he is to appreciate African-American culture. His review of the series The Wire has got to be the ne plus ultra of the genre:

One of the greatest works of art I’ve experienced in any medium. It unfolds with the kind of masterful pacing, sense of truth, reality, and tragic inevitability usually found in Tolstoy or Dostoevsky. It’s certainly the only TV show to alter my race conscious. I notice certain young black men who would have been invisible to me before, hidden behind the screen of my own ignorance and fear. I’d like to think I know something of their stories now. Awareness and compassion by themselves don’t change the world, but they’re a start. Speaking of which, did you know it’s Barack Obama’s favorite show, too?

This right next to a strip where he reacts to some jerky lady on the subway smacking him with her purse by coming home and beating a chair with his umbrella while shouting “YOU FUCKING NIGGER BITCH!” This incident just happened, too!

What I’m trying to say is that Heatley has loads more work to do on himself before he’s able to tackle this subject with anything remotely approaching insight or a worthwhile perspective. By contrast, when the original “Sex History” strip ends, you think to yourself, “Well, he’s aware that he’s behaved pretty ridiculously, and he’s trying much harder to be better about it.” Meanwhile, it’s not a “Woman History” strip where every female human he’s ever met is reduced to their primary and secondary sex characteristics, but a strip about his sex life–that’s a naturally proscriptive framework that I don’t think says anything untoward about how he views the people with whom he was sexually involved, male or female. You might have specific problems with how the focus is almost always on his pleasure rather than theirs, but that aside, the way he depicts sex–a combination of embarrassment, fun, awkwardness, beauty, predation, squalor, pleasure, depression, eroticism–maps pretty neatly to the way I imagine most of us have experienced it over the course of our lives. But “Race History”…I’m sorry, but if the word “nigger” occurs to you in anger, maybe it’s not your place to talk about which members of the Wu-Tang Clan had the best solo records?

This sort of retrospective inability to see that personal flaws require more than mere acknowledgment to be overcome gradually starts to bleed out into the other strips I once reacted more favorably to. The version of “Sex History” that appears here has been famously self-censored, placing neon pink bars across any images of penetration or ejaculation, and most erect penises in general. (It’s sort of like Greedo shooting first, only here, no one shoots at all.) A one-page epilogue added to the strip seems to reveal the rationale: Heatley has decided that his use of pornography qualifies as sex addiction, and through the help of a 12-step program he no longer uses porn or masturbates. Presumably, he’s neutering the strip to bring it in line with his newfound enlightenment. Now, this defeats the purpose of the strip, which is to be “apocalyptically revealing” as I once put it, and it’s sexist and hypocritical in an MPAA way, since you still see plenty of bush and titties. But worst of all, the 12-step higher-power imagery that pops up here and elsewhere–in the “Self-Portrait” strips that decorate the covers, the end of “Race History,” and the birth of Heatley’s second child in “Family History”–lends the whole affair a scent of sanctimony. Heatley has opened his life to God, God is literally cradling him in the palm of his hand, and however racist and sexually messed-up he may be, everything’s okay. But everything’s not okay! The first step is admitting you have a problem, but that’s only the first step! I know, I know, you can argue that Heatley is aware of all of this, that every moment of oblivious self-contradiction or narcissism or bigotry is committed to paper with full knowledge of exactly what it means. That’s fine, that’s fair, that’s probably actually true. That’s good enough for David Heatley the person, but it’s not good enough for David Heatley the artist. I need more.

Comics Time: Against Pain

December 3, 2008Against Pain

Ron Regé, Jr., writer/artist

Drawn and Quarterly, July 2008

128 pages, hardcover

$24.95

When it comes to art, I like to be able to get everything in one place. I don’t like it when bands leave the single off the album, and I want comic collections to contain every relevant strip they can. Yet I closed Against Pain, a collection of Ron Regé Jr.’s anthology contributions and one-off comics, wishing that it was shorter and contained less stuff. Regé is a cartoonist whose work I really treasure–I consider his Skibber Bee Bye one of my formative comics reading experiences and truly one of the best books of the decade, even now–but his oeuvre has at least as many misses as hits. That uniform line weight conveys the sense that everything is equally important, which is a core component of Regé’s philosophical project in most of his mature comics; the misses tend to be instances when this psychedelic, pantheistic take on both art and life comes across as mush rather than mind-expansion. Against Pain‘s flaw is that its editorial approach is similarly egalitarian, and similarly problematic.

In my experience, Regé is at his best when being his most ambitious. For example, Skibber feels like a freaking comet colliding with your brain, so big and sprawling and heavy is it compared to the rest of Regé’s usually much shorter works. Against Pain collects several, uh, let’s call them “suites” of comics that, though shorter, display genuine thematic fence-swinging. “We Must Know, We Will Know” (great title!), recently included by Ivan Brunetti in his second Yale University Press Anthology, is a series of candy-colored, interconnected strips about, of all things, math–how the unsolvable is solved, how models of certainty give comfort and how uncertainty gives freedom. A suite of “Pain” comics, I think created with funding from Tylenol (!), mines similar territory involving the mind’s hold on how we interact with the physical world, our own bodies included. There’s a lengthy Spider-Man parody called “High School Analogy” that works quite well as just that, but also reminds us how much fun the Spidey character can be when he really is a sullen teenage dirtbag and not a babe magnet. “She Sometimes Switched to Fluent English and Occasionally Used a Few Words of Hebrew,” the minicomic about a failed, female Palestinian suicide bomber that was included in Chris Ware’s McSweeney’s #13, contains perhaps the most direct articulation of Regé’s governing philosophy in the entire book: “All of our human lives are equally valuable*,” he says, before adding the footnote “or equally worthless…take your pick” as a seeming acknowledgment of the horrendous tit-for-tat brutality of this true story. It also presents a startling insight into the culture of young suicide “martyrs”: What if you lived in a place where low-level warfare could turn everyday teen angst into tragedy at a moment’s notice, and if there were organizations that thrived by transmogrifying that angst into violence? As a counterpoint, almost, there’s Regé’s legendary collaboration with his friend Joan Reidy, “Boys,” a series of simple nine-panel sex comics that are at turns lovely, funny, disturbing, sad, angry, and hot, which I induce from experience is likely many readers’ history with sex in a nutshell.

But there’s a lot of other stuff in here, and most of it isn’t nearly as successful. Perhaps counterintuitively given the rubric I just spelled out, one of the more frustrating strips is also one of the longest: “Fuc 1997: We Share a Happy Secret But Beware Because the Modern World Emerges” kind of tells you everything you need to know about its take on young love in the title, but continues for page after page of digressions, doubled-up strips per page, background colors that turn Regé’s wire-lined characters into oddly clunky forms, and just generally not-super-interesting lovelorn melancholy. A lot of the other material feels disjointed, Regé’s unorthodox layouts and wide-eyed narration throwing a lot of competing ideas and images at you all at once, often for just a page or two at a time before shifting to an entirely different strip and resetting what’s left of your attention span completely. A naive girl from the Balkans, an odd “sound sculpture,” a nearly incomprehensible cover version of a Lynda Barry comic about getting stoned, random splash pages, three dream comics crammed into one strip you have to read in tiers…like I said, it’s a lot of stuff to get a handle on, with very little to help you do so or, at times, to show you why you’d want to. The book ends with one of the odder choices I’ve seen from an anthology lately, back-loading most of Regé’s older, rougher, less visually mature work. It’s sort of like a Chris Ware anthology that contains that thing from Building Stories about housesitting or the World’s Fair issue of Jimmy Corrigan but ends with a solid chunk of Potato Head strips.

Listen, I’m extraordinarily grateful that a big, hardcover anthology of Ron Regé strips exists. After Highwater closed down, who even thought that would be possible? Seeing Against Pain on my bookshelf makes me wonder which Earth in the Multiverse is the one we’re on, and where Superman’s rocketship landed to change history so that comics projects like this could go from “you’ve got to be kidding me” to “buy it for 20% off on Amazon” in about half a decade. And again, I’m grateful to have all the comics I listed a couple paragraphs ago in one accessible place. And since I’ve never felt that Regé’s overall career was a model of consistency, I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised that his career-spanning anthology isn’t either. I can do the editing in my head, and I will, because all comics are not equally valuable, or equally worthless.

Comics Time: The Adventures of Tintin: The Seven Crystal Balls

December 1, 2008The Adventures of Tintin: The Seven Crystal Balls

Hergé, writer/artist

Little, Brown and Company, 1975

62 pages

$10.99, not adjusted for inflation

You know what reading this reminded me of? Watching the Wachowski Bros. Speed Racer. Maybe it’s the luscious candy colors, maybe it’s the miraculously smooth line, maybe it’s the rounded figures, but in much the same way that Speed Racer aspired to be nothing but a wholistic yet obviously CGI world, Tintin is clearly a cartoon, yet draws your eyes in irresistibly and sensually, as though you could predict what would be behind every tree, what you’d see if you turned around and looked in the other direction, what the backs of each character look like when they’re facing front. I think what I’m trying to say is that it’s fluid? You could jump right in and move around. Obviously the panel transitions help a great deal: Hergé often adds what would appear to be extraneous frames of Tintin walking from here to there, or an extra beat or two during a conversation, just to give a slightly more total sense of Tintin’s world. He also ever-so-slightly violates the 180 degree rule now and then as his characters move from place to place–he does it as they shift direction so you don’t notice it as much, but it reinforces that sense that if you spun a camera all the way around them in any direction, that pastel world of lines and shapes and colors would be visible the whole time. Immersive, maybe that’s the word too. Man, what a stylist!

Plotwise it’s, y’know, kind of slight: The members of a Peruvian archaelogical expedition that unearthed the mummy of an Incan ruler are being systematically assaulted by some sort of gas or powder that’s knocking them into comas; the dispersal method appears to be shattered crystal balls. During the investigation, Tintin’s friend Professor Calculus is kidnapped. There’s a shootout—now that’s what kids’ entertainment needs these days!—but the kidnapper escapes with Calculus in tow. It actually is rather engaging for its simplicity (I was curious to discover just how the kidnapper’s getaway car dodged the cops), the comic business is often funny (I liked Snowy the dog’s ill-fated attempts to chase Captain Haddock’s cat), and I guess it’s just my ignorance of the European album format that had me feeling gypped that the book ended without resolving the story. Newsflash: Tintin is a fun comic.

Comics Time: New Construction #2

November 28, 2008New Construction #2

Kevin Huizenga, Ted May, Dan Zettwoch, writers/artists

USS Catastrophe, October 2008

44 pages

$3

Let’s be honest, this is a collection of thumbnails by the three St. Louis-based cartoonists listed above. If you’re not in a bit of an “I’ll buy any new thing Kevin Huizenga puts out” mode it’s probably not worth your time. However, it does afford you the opportunity to marvel at how many good ideas Huizenga throws out, even though this doesn’t cohere into a beautiful idea-in-itself as did Untitled, Huizenga’s earlier, manic sketchbook/notebook-minicomic about searching for a title for his series. It’s fun enough to see the thumbnail versions of familiar pages and covers from comics like Fight or Run, “The Curse,” “Jeepers Jacobs,” Ganges and so on, considering that those comics are rather era-defining. And I really liked the opening two pages, in which Huizenga offers an explanation of his thumbnail process that, by the time he starts speaking of acheiving “thumbnail mind,” reveals itself to be a pastiche of religious tracts. In general? I mean, you’re going to know going in how interested you are in a Huzienga/May/Zettwoch sketchbook kinda thing. It’s the definition of YMMV.

Comics Time: Batman #681

November 26, 2008Batman #681

Grant Morrison, writer

Tony Daniel, artist

DC Comics, November 2008

40 pages

$3.99

First things first: The Black Glove is not a person but a five-person consortium of, as Brad Majors would put it, “rich weirdos”—a general, a priest, a dude in Arab headgear, a businessman, and Jezebel Jet. Their ringleader-type person is Doctor Hurt. Doctor Hurt claims, for the second time, to be Batman’s father, Thomas Wayne, and for the second time this suggestion is shot down (first it was Alfred, this time it’s Batman himself). Batman theorizes he’s Mangrove Pierce, Wayne lookalike and actor in a film called The Black Glove that was at the root of his earlier case involving John Mayhew and the Club of Heroes, but Hurt shoots that notion down in turn, instead saying, “I am the hole in things, Bruce, the enemy, the piece that can never fit, there since the beginning.” Batman rejects Hurt’s offer to spare the reputation of his parents and Alfred in exchange for servitude, then leaps up and crashes Hurt’s getaway copter, plummeting to his “death.”

That’s the gist, anyway. People expecting real answers about any of this are rewarded with not a whole lot more than people looking for a convincing Death of Batman are. So what do I take away from the conclusion to the big “Batman R.I.P.” arc? Well, it was a lot of fun–this is about as involved as I’ve been in a superhero storyline since I started reading the things again in 2001; moreover, this is the first single issue of a superhero series I’ve purchased since, I think, August 2004. Morrison’s Batman is about what it wants you to do–it presents itself as a dizzying series of clues and references that only the sharpest mind can unravel. What I didn’t expect was for the rug to be yanked out from underneath it all–the Joker revealing that all his red/black symbolism stuff was made up, Doctor Hurt revealing (I think!) that his origin is that he has no origin to speak of, at least as far as existing Batman lore is concerned. (This may or may not be true–he really could be Thomas Wayne, or as one friend suggested, he could be Thomas Wayne Jr. of JLA: Earth-2, aka Owl-Man. It would fit the alternate history Hurt presents in which Joe Chill kills Martha and Bruce.) But the kicker is that even with all its intricate structure and symbolism revealed to be a put-on, Batman still kicks the shit out of the Black Glove. The main narrative thread of this final issue is a Bourne-type situation where we discover Batman’s just plain too smart and strong and sharp for these clowns to possibly beat him. In fact, what looked like abject failure a few issues ago was really just a product of Batman’s sheer confidence in his own ability to have somehow prepared himself for any eventuality. That’s just how awesome he is.

For skeptics of Morrison’s pro-awesomeness philosophy of superhero comics, I’d imagine this is going to fall pretty flat, but I’m down with awesomeness from time to time, if not as much as your average Barbelith poster or comicsbloggers who use the word “pop” a lot. I’m certainly down with awesomeness from Batman, my favorite character, written by Morrison, my favorite Big Two writer. The idea that Batman created a nutso backup personality in case the shit ever really hit the fan? That’s fantastic. Can I also take this time to give a shout-out to the much-maligned Tony Daniel? I’ve been a bit baffled by the guff he’s been given, seemingly primarily by dint of not being Frank Quitely. I think his Batman has been consistently tough and badass–I like it better than Jim Lee’s similar yet much less crazy take–and he’s done some really spooky stuff with the Joker. There’s some really nice fight choreography in here too with Robin and Pierrot, too, and in general I haven’t found his fights or layouts as incomprehensible as many others have. In sum I enjoyed this storyline and even though I’m still not quite sure what happened, I’m okay with that.

UPDATE: Did you know there are two additional Grant Morrison Batman issues coming out before his hiatus from the book? I sure didn’t!

Comics Time: Big Questions #11: Sweetness and Light

November 24, 2008Big Questions #11: Sweetness and Light

Anders Nilsen, writer/artist

Drawn and Quarterly, November 2008

48 pages

$6.95

Big Questions #11 contains enough wow moments to sustain your average cartoonist’s career for several years. The latest installment in Nilsen’s series about the reaction of various birds and animals to a plane crash in their midst is pretty much one bravura sequence and image after another. The wild dogs coming thisclose to eating the sleeping crash survivor…the pilot’s fever dream of a monstrous swan erupting from the earth…carving the swan open to unleash a maelstrom of bloodsoaked birds…the mocking, sinister blackbird who refers to carnivores like himself as “the walking, flying dead,” since you are what you eat…the pilot’s second dream, where he quietly tends to the other survivor…the wounded bird who spends the entire issue dragging himself across the ground by his head, just to climb a hill where he can see the sunrise on the final page. As an artist Nilsen continues to grow, doing things (like the inky, frightening flock of birds that fly out of the slain swan) I’ve never seen him do before and doing them wonderfully well. It’s Wild Kingdom directed by David Lynch, suspenseful and rapturous, a comic of terrible sadness, horror, and beauty.

Comics Time: I Live Here

November 21, 2008I Live Here

Mia Kirshner, J.B. MacKinnon, Paul Shoebridge, Michael Simons, primary writers/artists

Ann-Marie MacDonald, Lynn Coady, Joe Sacco, Kamel Khélif, Chris Abani, Karen Connelly, Tara Hach, Lauren Kirshner, Valerie Thai, Niall McClelland, Seamrippers Craft Collective, Tina Medina, Julia Feyrer, Tiffany Monk, Charlotte Hewson, Sean Campbell, Phoebe Gloeckner, Julie Morstad, Karen Comins, Lackson Manyawa, Felix Yakobe, Edward Kasinje, contributing writers/artists

Pantheon, October 2008

320 pages

$29.95