Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

Comics Time: Invincible Iron Man #19

October 23, 2009

Invincible Iron Man #19

Matt Fraction, writer

Salvador Larroca, artist

Marvel, October 2009

40 pages

$3.99

It’s been a long time since I read superhero comic that wasn’t by Grant Morrison more than once out of enthusiasm rather than confusion. But golly, I enjoyed this one, and I enjoyed it just as much the second time around.

Subtitled (somewhat pretentiously) “Into the White (Einstein on the Beach),” this is the conclusion of the year-long “World’s Most Wanted” arc of Fraction and Larroca’s movie-toned Iron Man book, in which the disgraced and deposed Tony Stark runs around the world trying to destroy both his tech and his own mind lest both fall into the hands of new King Shit of Turd Mountain Norman Osborn. In the past I’ve found this set-up very hard to swallow because of how dependent it is on other, lesser comics like Civil War and Secret Invasion. For example, I don’t care what universe you live in, if Bernard Kerik can go from Homeland Security chief nominee to getting his mugshot taken, it strains credulity that a guy who used to dress up as a goblin and throw pumpkin bombs at people is gonna get put in charge of jack shit.

But Fraction compensates for this inherited conceptual sloppiness simply by making the plot mechanics for this story as tight as he possibly can. He cuts relentlessly back and forth between the protagonists and antagonists: the Charlie’s Angels trio of Black Widow, Maria Hill, and Pepper Potts attempting to escape from Osborn’s lair; Osborn’s second-in-command Victoria Hand trying to prevent this and quaking in terror of what will happen if she doesn’t; Osborn himself cockily closing in on his quarry; the intelligence-officer grunt who’s secretly feeding Osborn bad information and the colleague who smells something fishy about him; and Iron Man himself, experiencing an Algernon-like loss of his faculties as he hurls himself in his dilapidated old armor toward his final destination. If you’ve ever tried to write an action sequence, let alone cross-cut between several of them, you know how hard it is to get what needs to happen to happen for any reason other than your need for it to happen, right? Well, never once do the A-B-C sequencings of Fraction’s various plots feel like they’ve skipped a letter just to get to point Z quicker. From the captured spies moving up and down and in an out of an elevator, to the precise interpersonal dynamics between all the personnel involved in Norman’s pursuit of Tony Stark, each moment proceeds directly from the last, whether physically or emotionally.

How many fight scenes have you read lately where a character will get smacked several dozen yards by some giant powerhouse only to be up and about a few pages later? How many times have creators had to go online to clarify the physical fate of a character whose beating they wrote into incomprehensibility? How many times has a climactic battle been undercut completely by glib banter, almost completely disconnected from the circumstances of that place, that moment, those characters? You’re not gonna get any of that shit here. Each scene and sequence feels like it’s taking place in a physical space you and the characters could navigate, with physical maneuvers having readily understandable physical consequences. Each move toward and away from the characters’ goals comes with a sense of the stakes involved–the grand illusion of serialized shared-universe superhero storytelling, that there really can be winners and losers, has rarely been so astutely conveyed.

This is all the result of what feels like a real partnership. This issue’s success is equally due to Fraction’s just-right dialogue and direction and Larroca’s deft work with body language and fight choreography. (His days as a Greg Land-style spot-the-photoref novelty act are loooooong behind him.) Both shine brightest in the climax, making Osborn’s slide from glee to rage to frustration to confusion to defeat snatched from the jaws of victory as clear as day and almost frightening. It’s capped off with a one-liner in which the totality of Tony’s pwnage of Norma is made hilariously clear (provided you’re a Marvel nerd), and a one-page coda that manages to set up the coming mega-crossover without losing a sense of beatific victory and loss.

Did I mention that they managed to rehabilitate Iron Man’s badly damaged character in my head, despite the fact that even now none of his actions during Civil War have turned out to make any kind of practical or moral sense within the world of the story in any way? And that they managed to establish Spider-Man villain the Green Goblin as a for-the-ages Iron Man enemy as surely as Frank Miller made Kingpin the archnemesis for Daredevil? I dunno, man, this is some mightily effective work in this genre. I feel like it should be taken apart and studied at story summits for a long, long time: If this is what you want to do, this is how you want to do it. Aw, hell, I’m gonna read it again.

Comics Time: Slow Storm

October 21, 2009

Slow Storm

Danica Novgorodoff, writer/artist

First Second, 2008

176 pages

$17.95

This is like half of a good book. The visual half, for the most part. Danica Novgorodoff’s story of a Kentucky firefighter and the undocumented Mexican worker she kinda sorta befriends after a fire claims the stable he tended is a stunning-looking thing. She has a wiry line that often suggests handwriting, with all its idiosyncracies, so that the occasional wonky scale or perspective seems like (or can be passed off as) a deliberate choice. Individual moments beam out a little Taiyo Matsumoto, a little Ralph Steadman, a little Gerald Scarfe, only with the dial turned from savage to lilting. And her watercolor coloring takes a limited palette of greens, browns, grays, and oranges and fleshes out the artwork so lushly I barely even realized just how few colors she limited herself to in the first place. It’s in the moments where she really draws with the colors–a creek, a tornado, the omnipresent cloud and fire motifs–that the book comes alive.

But its in moments where the dialogue takes the lead where it sputters. Frequently too portentous–every conversation creaks under the weight of capital-M Meaning–it fails to convince us of firefighter Ursa’s shattered psyche, so that when she perform’s the book’s central act it feels like a horrifying, selfish overreaction. Which, granted, it’s supposed to feel like, but you’re also supposed to think “okay, I could see where that came from,” whereas I just thought “Christ, what a fucking maniac.” Ditto her behavior during the event’s fallout, which adds “asshole” to the equation. Meanwhile, Rafi, the Mexican immigrant, is laden with poetic visions of saints and white horses–it’s just laid on too thick. The key for Novgorodoff (an Isotope winner and Eisner nominee who clearly doesn’t need any advice from me but what the hey) will be to scale back her swing as a writer and tell a story as understated as her art is sweeping.

Comics Time: Driven by Lemons

October 19, 2009

Driven by Lemons

Joshua W. Cotter, writer/artist

AdHouse, September 2009

104 pages, hardcover

$19.95

Buy it from AdHouse, eventually

So yeah, this is pretty much the ideal Josh Cotter comic for me. Didja like the bizarre, symbol-laden wordless reveries of Skyscrapers of the Midwest? Here’s a whole book full of them! This shit makes the locust/migraine sequence from Skyscrapers #2 look like Dilbert! What’s it about? In large part, who cares? Like (in my experience) most great comics, it’s about how, and what, it makes you feel. It makes me feel like one of those ’80s special-effects sequence where some being’s exterior shell is chipping away and beneath each chunk that falls off a blindingly bright white light shines out like a beam–like that’s basically what Cotter did to his own brain to produce this thing, and like that’s what you run the risk of if you stare too long.

That’s essentially what Cotter does, visually, over and over again throughout the book: Something will cause one of Cotter’s nominal protagonists (anthropomorphized Life in Hell bunnies, pretty much) to spew forth from his person an amount of visual information that totally overwhelms them and the page itself, scribbled and scribed like a Charles Crumb notebook, and at one memorable point caked/painted with watercolors squeezed straight from the tube. In that light, and considering the first section’s apparent Chicago setting and slow evolution into comics from a straightforward-ish stream-of-consciousness prose-plus-doodles diary format, it’s tempting to read the book as some sort of autobiography: a story of the onset of, treatment of, and recovery from mental illness. For what it’s worth, I interviewed Cotter about his life and work at length for The Comics Journal and such an incident never came up, though I could have just whiffed on it. If I’m wrong, so much the better for Cotter, because having dealt with the mental-health institutionalization of two people very very close to me, this is about as accurate a representation of what I always pictured going on in their heads as you’re gonna find. Noise, blotting out signals and forming its own.

Glorious noise, too. For all of the books insular inscrutability, several passages here stand out with an effect as awe-inspiring as a great visual effects sequence in a blockbuster by some genuine Hollywood visionary. The paint explosion. The great cloud of scribble, with sensuously tangled lines looking like they’ve somehow been carved through other lines. The marvelously reproduced, bright reds and blues representing warring states of mind, popping off the off-white pages like 3-D. (The whole book, a facsimile of Cotter’s sketchbook, is really an astonishing work of design by Cotter and Chris Pitzer.) The forward momentum of the chase sequence, with two bunnies battling for supremacy in frame after Haring/Muybridge mash-up frame. An eruption of a column of red that rockets into the sky so powerfully you can practically hear the noise. And a creepy cameo by the mad god Dionysus, quoting the soundtrack from the animated Transformers movie, rings out as a reminder of madness after all is said and done like that dissonant shot of the cab’s rear view mirror at the end of Taxi Driver.

Outstanding work. Where the hell does he go from here?

Comics Time: Abstract Comics

October 16, 2009

Abstract Comics

Andrei Molotiu, editor

R. Crumb, Victor Moscoso, Spyros Horemis, Jeff Zenick, Bill Shutt, Patrick McDonnell, Mark Badger, Benoit Joly, Bill Boichel, Gary Panter, Damien Jay, Ibn al Rabin, Lewis Trondheim, Andy Bleck, Mark Staff Brandl, Andrei Molotiu, Anders Pearson, Derik Badman, Grant Thomas, Casey Camp, Henrik Rehr, James Kochalka, John Hankiewciz, Mike Gestiv, J.R. Williams, Blaise Larmee, Warren Craghead III, Janusz Jaworski, Richard Hahn, Geoff Grogan, Panayiotis Terzis, Mark Gonyea, Greg Shaw, Alexey Sokolin, Jason Overby, Bruno Schaub, Draw, Jason T. Miles, Elijah Brubaker, Noah Berlatsky, Tim Gaze, Troylloyd, Billy Mavreas, writers/artists

Fantagraphics, 2009

232 pages, hardcover

$39.99

Visit the Abstract Comics blog

One of the pleasures inherent in anthologies is the way proximity draws out the contrast between successful and unsuccessful work. One of the unique pleasures of this anthology is how that success or lack thereof can be determined not just by the subjective standards of the reader but also by the ostensibly objective standards of the anthology itself. In his introduction, editor Andrei Molotiu defines abstract comics thusly:

What does not fit under this definition are comics that tell straightforward stories in captions and speech balloons while abstracting their imagery either into vaguely human shapes, or even into triangles and squares. In such cases, the images are not different in kind, but only in degree, from the cartoony simplification of, say, Carl Barks’ ducks….While in painting the term [“abstract”] applies to the lack of represented objects in favor of an emphasis on form, we can say that in comics it additionally applies to the lack of a narrative excuse to string panels together, in favor of an increased emphasis on the formal elements of comics that, even in the absence of a (verbal) story, can create a feeling of sequential drive, the sheer rhythm of narrative, or the rise and fall of a story arc.

True, none of the comics featured here use (legible) captions or speech balloons. But as Molotiu’s subsequent emphasis on “images” implies, the lack of text is incidental to the more fundamental lack of narrative or story. It’s by that petard that several of the strips Molotiu selects are hoisted. The contributions from Ibn Al Rabin, Lewis Trondheim, Andy Bleck, and to an extent Mike Gestiv and Bill Shut all rely precisely the sort of “difference in degree” Molotiu warns about–in their comics, abstracted shapes perform actions based on recognizable, and in some cases quite clearly depicted, physical motivations and even emotions, just like the “triangles and squares” we’re told may as well be Uncle Scrooge. These strips are cute, but not exactly challenging, and far from abstract.

But the successful strips in Abstract Comics prove that comics need not depict emotions to pack an emotional wallop. Indeed, part of my long-held enthusiasm for this project stemmed from my suspicion, based on steps (small and giant alike) in the direction of abstraction during this decade by such alternative comics artists as Kevin Huizenga, John Hankiewicz, Anders Nilsen, Josh Cotter, and Frank Santoro, that abstract comics stripped completely away from their narrative moorings–abstract comics “in the wild,” as it were–had the potential to generate emotional content of enormous power. What I didn’t expect was just how…I don’t know, idiosyncratic my reaction to such comics would be.

For example, I’ve already described how the more openly narrative works contained here elicited a chuckle but not much else. What’s interesting to me is how the sorts of shapes used by those artists–outlined blobs, for the most part–left me cold even in purely abstracted form. The squiggles of Elijah Brubaker, the whorls of James Kochalka, suggest a warmth and an airiness I’m just not tuned into at all. I’m not a curve man, it turns out. Meanwhile, I’m equally unaffected by strips that eschew drawing sharp contrasts from image to image and panel to panel, either by muting the differences between juxtaposed visuals (Warren Craghead, Richard Hahn, Janusa Jaworski) or by weakening or eliminating the parametric framing and structure provided by panels (Noah Berlatsky, Billy Mavreas, Troylloyd, Tim Gaze, Bruno Schaub).

What I am interested in, it appears, are angles. boxes, cold geometry. Jason Overby’s “Apophenia” is perhaps my favorite comic in the whole book: Beginning with a grid of penciled-in panel borders containing nothing at all, it proceeds to flash various sharply carved shapes into panels at random intervals like sudden words emerging from a haze of silent static, or subliminal messages erupting from a blank screen. Mark Goneya’s “Squares in Squares” is just that, panel after panel of brightly colored squares surrounding one another like an infinite regression, their position within the panel shifting slightly to slow our eye’s descent into the abyss. Mutts creator Patrick McDonnell’s untitled, college-vintage contribution uses a repeated bisected-circle motif in black, white, and watercolor-blood red to suggest cold sunrises and magisterial eclipses. And Spyros Horemis black-and-white concentric circles and swirls practically glow off the page with the force of an optical illusion.

I’m also interested in a sense of awe and scale. Molotiu’s own excerpts from The Cave overwhelm with bright colors and massive slopes that dwarf panel borders and seem to escape his control, like a microscopic process blown up to IMAX size or a projected filmstrip set on fire. Henrik Rehr’s “The Storm” is as aptly named as was “Squares in Squares”: Great waves or windgusts toss us to and fro across black backgrounds, sending tiny offset panels scattering like leaves. Alexey Sokolin’s “Life, Interwoven” sees its panels slowly overwhelmed by furious black scribbling, like a diary of a madman, until it not only totally blots out the grid but appears to topple it over.

And sometimes I’m like John Cleese’s pope: I may not know art, but I know what I like. I like the loneliness of Blaise Larmee’s tiny, shaky, frail, incomplete rectangles against their off-white background in his Nilsenesque “I Would Like to Live There.” I like the humor of Geoff Grogan repeating a bullseye motif until the laugh-out-loud punchline photo of a woman’s nipple in “Bullseye.” I like Jason T. Miles creating shapes out of chunky, semi-monstrous black and white lattices–Brinkman Blocks, if you will–then signing it with a great big clumsy JASON T. MILES in “Mainstream Blackout.” I like the implied sequentiality of Mark Badger following up a pencil-sketched “Kung Fu” strip from 1980 with a boldly colored remake of the same strip from 2008. And I like the pure psychedelia–in the information-overload sense–in R. Crumb’s “Abstract Expressionist Ultra Super Modernistic Comics,” drawn, laid out, and even titled as though attempting to get it down on paper winded him.

So. By my count I liked, mmm, about half the book, give or take a couple strips. And there are potentially fruitful paths that remain largely untrodden. For example, I know Molotiu has been doing yeoman’s work on carving out a space for nonnarrative comics for years because I remember jostling with him a bit about on the Comics Journal messageboard following the release of Kramers Ergot 4 in 2003; however, the work of Fort Thunder and its fellow travelers, showcased so memorably in Sammy Harkham’s anthology, isn’t represented here (unless you count their spiritual godfather Gary Panter). Meanwhile, Crumb and Larry Zenick excepted, the use of representative figures in an abstract way is elided here; I wish Molotiu had selected one of John Hankiewicz’s enormously effective strips in this style rather than the comparatively staid and painterly contribution we see here. And for my money, the sequencing peters out toward the end–I’m not sure what I was supposed to take away from the final strips, rather formless black and white affairs. An editorial focus not so much tighter as tweaked, I suppose, is what I’m looking for.

But what I liked! What I liked, I liked for more than just the strips themselves–I liked them for the proof they offer that comics really is still a Wild West medium in which one’s bliss can be followed even beyond the boundaries of what many or even most readers would care to define as “comics.” That an entire deluxe hardcover collection of such comics now exists is, I think, one of the great triumphs for the medium in a decade full to bursting with them. And even if the book’s existence is ultimately more impressive than the sum total of its contents, it strikes me as churlish to complain.

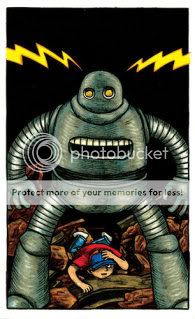

Comics Time: Sulk Vol. 3: The Kind of Strength That Comes from Madness

October 14, 2009

Sulk Vol. 3: The Kind of Strength That Comes from Madness

Jeffrey Brown, writer/artist

Top Shelf, September 2009

64 pages

$6

I still don’t get where this whole “Jeffrey Brown can’t draw” thing comes from. I mean sure, if your standard for artistic excellence is Neal Adams or something, you’re gonna be like WTF, but as always I’m ignoring those people and talking about altcomix fans who should know better. I’ve said this before, but compare the work of Brown (full disclosure: I like him a lot personally) to that of any of the ultra-lo-fi slice-of-life humor/pathos diarists who’ve emerged in his wake and he’s just doing so much more–with how he arranges space in his panels; with how he adds line upon line for shading, depth, and detail; with the expressiveness of his characters; with how even his action pastiches are genuinely dynamic and fun to follow; with how he bounces from genre to genre with the same “here’s something I thought was funny about this topic” good humor. Especially in the outright humor stuff, he’s like your funny friend bullshitting.

That’s not necessarily to say that everything he does is for everyone. As in previous genre-parody works like Incredible Change-Bots, the sci-fi/action/fantasy hodgepodge of Sulk #3 presupposes simultaneous knowledge of, affection for, and skepticism of the kinds of stuff he’s swiping from/at, plus (obviously) an appreciation of Brown’s visual approach to the material. It’s an acquired taste: The ribbing might be too gentle for people who wanna see an indie stalwart get some yuks at the expense of elves and unicorns, while the irony might be tough to stomach for po-faced “new action” fans. Indeed I think the reason why Brown’s Bighead books (including Sulk #1) are the strongest of his work in this area is because this kind of parody is more familiar with superheroes than with any other subgenre; you can “get it” easier than you can when you’re dealing with pirates or D&D or Godzilla or boy geniuses as you are here. Meanwhile the MMA-based Sulk #2’s 80-page fight scene was easy to grok as an exercise in ways drawing combat and writing the combatants’ interior monologues. The anchor point in The Kind of Strength That Comes from Madness is much harder to locate.

I suppose it just comes down to what you think you might want to see in a comic. Do you want to see an adorable, realistically depicted stag smack his antlers against a tree and then stare at the reader, demanding to know “DO YOU STILL WANT TO TANGLE WITH ME?” in giant capital letters? Do you want a ground-eye-view parallel to Brown’s memorably poetic giant-monster rampage comic from Mome in which a couple of moron brothers take the opportunity to make a “looting list” out of their weekly grocery list and then smack the dying reptile around with a baseball bat? Do you want to read lines like “A vampyre! It’s exactly like a vampire, but far more dangerous,” or hear small-city residents thank goodness that the giant monster is attacking their town instead of big important places like New York or L.A.? Do you want the occasional visual digression about boobs or beards or babies? I know my answers at least.

Comics Time: Cold Heat #7/8

October 12, 2009

Cold Heat #7/8

BJ & Frank Santoro, writers

Frank Santoro, artist

PictureBox, September 2009

48 pages

$20 (hey, it’s a limited edition of 100)

Radiohead threw me not when they made their shift into electronic music with Kid A–I’d been listening to Aphex Twin since I was a sophomore in high school, yeah that’s right, I’m an IDM OG, or at least as close as we got to one on L.I.–but with the two albums after that, Amnesiac and Hail to the Thief. I now listen the heck out of those records (okay, more Hail than Amnesiac), but the band’s sudden lack of interest in providing the big, sweeping, soaring moments of catharsis they were still doing as late as “How to Disappear Completely” and “Morning Bell” struck me then and now as a willful avoidance of their own strengths. Now they’re doing that sort of stuff again on In Rainbows and all is well with the world, but I do wish that more people would acknowledge that guitar rock or no guitar rock, that was the big, not-entirely-successful risk they took this decade.

Something similar is going on in Cold Heat #7/8. For about 4/5ths of this limited-edition double-issue installment of Santoro & Jones’s punk-rock sci-fi saga, the psychedelic vistas and geometric reveries that were the series’ aesthetic calling card are largely abandoned. In their place is a comparatively straightforward, albeit tongue-in-cheek, international espionage quasi-parody involving cynical jetsetting journalists, deadpan quip-dropping CIA agents, sinister pharmaceutical conglomerates, crooked conspiring politicians, and Castle, the small-town American fuck-up who’s unwittingly unravelling the plot. Silence is rare, with more voluminous dialogue and lots of those little labels Santoro likes to drop in. It’s the sort of thing some combination of Stephen Soderbergh, George Clooney, and Matt Damon might release in a limited September theatrical run, or what you might see in one of the Coen Brothers’ seriocomic conspiracy-caper flicks if they were given an effects budget and asked to throw something spacey in there now and then. There’s even some broad comedy about the U.K. rock press and a celestial poker game involving not-exactly-dead rock star Joel Cannon being invited to play a hand with Jimi, Janis, Jim, and John. (Jerry opted to kick it in the hot tub.)

This ain’t your father’s Cold Heat, long story short. Honestly it’s so different in tone it feels more like a particularly off-model Cold Heat Special than a Cold Heat proper. And it may not be the droids you’re looking for–at least until the very end, where Castle searches for her kidnapped journalist lover, running through the streets of Rio in a wet bathing suit, fleeing the psychic and physical attacks of the evil Senator Wastmor’s puppetmasters. That’s the sort of dreamlike/nightmarish imagery you’ve come to expect from Cold Heat, and it’ll be interesting to see if there’s more of that in the offing, perhaps wedded to the new potboiler-parody structure we’re seeing here. Here’s hopin’.

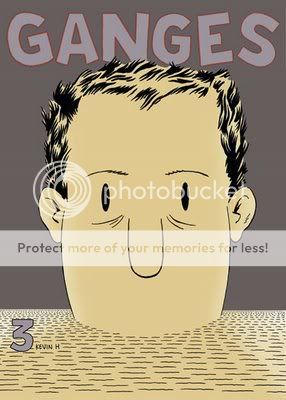

Comics Time: Ganges #3

October 9, 2009

Ganges #3

Kevin Huizenga, writer/artist

Fantagraphics/Coconino, September 2009

32 pages

$7.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics, eventually

You wanna talk about a gateway comic? How ’bout handing this sucker to anyone who’s ever had trouble falling asleep? The whole thing is dedicated to nothing more or less than reproducing the mental and physical sensations of insomnia. Ironically it’s Huizenga’s most action-driven comic this side of Fight or Run or the video-game bits in Ganges #2. In order to evoke the insomniac mind’s uncontrollable wanderings, Huizenga takes Glenn Ganges’s mental avatar and sends him on a series of Cave-In-like explorations–dipping him into water, sucking him down the drain, walking him up a tree, bouncing him off thought balloons, floating him along on sleep bubbles. At one point he mentally fends off invisible burglars; at another he’s armed with a bow and arrow, or a machine gun, taking aim at his own wiredness. Combine it with one of the most effective uses yet of the Ignatz series’ two-tone color palette–here a cool small-hours blue–and the experience is almost tactile, as though you’re physically tunneling through the mysteries of your own mind. It’s only when Glenn finally gives up and gets out of bed that the gutters switch from black to white and everything instantly feels less dense, less close; naturally, removed from the million-miles-a-second flow of his Glenn’s thoughts and reset in the real world, the action switches from complex reverie to straightforward cutesy business involving playing music late at night and freaking out when the cops show up about the noise. The mastery of tone is deeply impressive.

Look, I’m always gonna be up front about how I think the “Gloriana” issue of Or Else, #2, is the best thing Huizenga’s ever done. That thing hit me with the force of a revelation, and so I tend to be deaf to the claim that he keeps getting better and better. (Particularly regarding Ganges #1 and its disastrously wrong take on the Beatles’ “She’s Leaving Home”!!!!!!1!!111!) That’s as good as he’s gotten. But it’s obviously true that each new release proves just how much he’s mastered the stuff of comics, and how thoroughly he’s staked his claim on chronicling areas of contemporary American human experience few if any other cartoonists are going anywhere near. It’s pretty darned exciting.

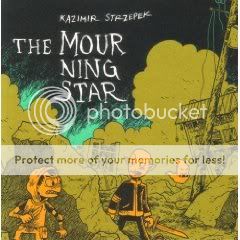

Comics Time: The Mourning Star #1 & 2

October 7, 2009

The Mourning Star #1 & 2

Kazimir Strzepek, writer/artist

Bodega, 2006 & 2009

Vol. 1: 220 pages

Vol. 2: 256 pages

$13 each

Of all the alternative action-adventure comics I’ve been lumping together in discussions for the past couple years, Kaz Strzepek’s The Mourning Star is the ripest candidate for crossover success. His cartooning is clear and appealing, with endearing, often adorable character designs and well-choreographed action sequences, reminiscent of the work of Brian Ralph without Ralph’s ars gratia artis, printmaking-derived design sense. Strzepek’s world-building–in the sense of both “backstory” and “readily understandable physical environment”–is top drawer, recalling everything from Dungeons & Dragons to Tolkien to The Road Warrior to The Dark Tower without coming across like a rehash of any of them. While its blend of an obviously personal vision with universally accessible ideas and visuals puts it more in line with Scott Pilgrim than Powr Mastrs, the involvement of Highwater vets Randy Chang and Jordan Crane in its production leaves little doubt as to its altcomix cred. It’s like a post-Fort Thunder Bone.

In reading The Mourning Star‘s first two volumes back-to-back recently, what struck me hardest wasn’t the admittedly rock-solid introduction to the characters and world provided by book #1, but the time we spend with its villains in book #2. It’s very easy and tempting for one’s grown-up, self-aware genre art to willfully return to a black-and-white conception of protagonist and antagonist. And I don’t blame anyone for doing it! The point of escapism is to escape, and giving your villains big black hats is a welcome relief from the shades-of-gray nightmare we live in day to day. But taking the time to depict villainy as the result of relatable choices is rewarding in its own way. In Volume 2, we discover through Strzepek’s seamlessly natural dialogue that the Rule aren’t just sinister, unfeeling killers–although they’re that, too. They’re people who banded together in The Mourning Star‘s postapocalyptic world for security and safety and who believe their brutality is what can continue to ensure this. They have leaders whose approval they sometimes crave and whose orders they sometimes resent. They have medics to heal them when they get hurt, and equipment that breaks down. They’ve got seasoned veterans and wet-behind-the-ears rookies. They tell each other urban myths. They jockey for position and remember their lives before they became the barbaric rulers of the cities and wastelands. In short they’re just like anyone who’s ever shored up an evil regime–potentially normal guys and girls who at some point lost or deactivated their ability to empathize, who don’t mind ordering or supporting the murder of people they don’t know. Maybe that’s why I’m rooting even harder than ever for the good guys to beat them in the end.

Comics Time: Cold Heat Special #7

October 5, 2009

Cold Heat Special #7

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

PictureBox, September 2009

12 pages

I don’t remember how much it cost

Browse the Cold Heat shop, where it’ll probably end up eventually

Band logos are an interesting thing, and when they succeed at visually representing a band’s musical and aesthetic project, a pretty awesome thing. Which makes a lot of old-school heavy metal logos a baffling thing–instead of offering a clear, brandable distillation of the band, they’re often illegible to the point of incomprehensibility. (Spend some time on Obsidian Obelisk and you’ll see what I mean.) I suppose this is a tip of the hat to the uncommercial, underground nature of much of that music–it’s so not for you that the masses can’t even make out the band name. (“Songs for the deaf–you can’t even hear ’em!”) My favorite recent example of this aesthetic cropping up in comics is Rinzen’s title design for Paul Pope’s Batman Year 100, which combines past stabs at shaping the word “BATMAN” into a logo with an unmistakable and acknowledged metal vibe.

Michael DeForge’s Cold Heat Special combines this with a project that stretches the boundaries of “comics” in much the same way as Kevin Huizenga’s minicomic Untitled. That book was little more than page after page of scribbled, rejected names for Huizenga’s then-upcoming solo series Or Else. And though its contents were almost entirely text, it was at least as much intended to be viewed as read; like any comic, its contents accrued meaning through sequential juxtaposition, building into a memorable exploration of the creative process and the by-definition arbitrary nature of assigning signifiers to the signified.

DeForge’s work here is different, to be sure. For starters, it’s very, very metal: His eye-meltingly ornate band-logo versions of the names of various Cold Heat characters (including, of course, the pivotal noise band Chocolate Gun) frequently rely on motifs that evoke thorns, spikes, bodily fluid, scales, horns, lightning, fire, and in one memorable case a fist with the name spelled across the knuckles in spilt blood. It’s a far cry from Huizenga’s no-nonsense all-caps lettering. It’s also a far cry, in a lot of ways, from the aesthetic I tend to associate Cold Heat with: the hazy sensuality of shoegaze. It’s way more Cannibal Corpse than My Bloody Valentine. (There’s also at least one explicit homage that I caught–the lettering for Black Sabbath’s Masters of Reality, not to mention 1000 Homo DJs’ Supernaut EP.) But what this explosive, offensive, savage designwork does get at is the importance of POWER to the Cold Heat project: The violent power wielded by the sinister Senator Wastmor, the emotionally liberating power of Joel Cannon’s music, the self-discovery of internal power by our heroine Castle, and so on. It also reinforces Cold Heat as a sort of samizdata, an attempt to recreate the magic of the “lifeline music” that got us through our teenage years and the handmade, ramshackle media, from zines to mixtapes, that chronicled that community. Logos like these are meant to communicate just how important and immediate and irrepressible the art they’re a stand-in for is to its makers and consumers. In the context of Cold Heat, they make more sense than you’d think.

Comics Time: Cold Heat Special #6

October 2, 2009

Cold Heat Special #6

Chris Cornwell, writer/artist

PictureBox, September 2009

24 pages

I think it was $10

Chris Cornwell is the joker in the Cold Heat deck. The only Cold Heat Specialist who doesn’t create his installments of the spinoff series in collaboration with Cold Heat-proper cocreator Frank Santoro, he’s also the farthest afield from CH‘s usual tone of wistful, sensual menace and transcendence. His first CHS involved an assassin whose dayjob was rock stardom and the evil Senator Wastmor piloting a giant minotaur robot. Similarly, this issue is summed up by that gorgeous, iconic cover, featuring some kind of robed Satan worshipper rocking out; this leads into an opening sequence in which a band comprised of monsters “rehearses” by destroying their own equipment in a montage that reminds me of Yacht Rock’s take on Van Halen in terms of sheer half-parody/half-salute comedic rockitude.

Indeed the whole comic feels a bit like a montage. There’s that opening Monsters of Rock sequence’ a credits-spread scene of a nude Senator Wastmor getting drunk and drowning in an ocean of his own puke’ a “secret history of Cold Heat” story (really the core segment) about one of Wastmor’s ancestors attempting to sacrifice a beautiful girl to his demonic masters in colonial days before being thwarted by alien protectors; a near-abstract spacetime-rupturing transition sequence linking that centuries-old adventure to the present-day viewing of a Chocolate Gun videocasette by other aliens; and a glimpse of how the aliens’ power affects CG lead singer Joel Cannon juxtaposed with how Cannon’s music effects Cold Heat heroine Castle. Got all that? It can be tough to follow, particularly toward the end of the book, but following it doesn’t appear to me to be the point. It’s more a case of latching on to isolated images and impressions, meaning that Cornwell in his goofy slapstick way is mimicking the more lyrical approach of Santoro and Ben Jones in Cold Heat itself. And he can do it, too–he’s got the visual chops to bounce back and forth between slick cartooniness (the cover, Wastmor’s bender), rough-edged Fort Thunder/Closed Caption Comics-style monstrousness (the band, the aliens), non-narrative visual-driven psychedelia (the transition sequence), and on the last two pages, a glimpse of Cold Heat‘s trademark music-as-emotional-salvation leitmotif. Plus the book is as lovely an object as the CHS series has seen so far, with that killer, please-make-it-a-poster cover and two gorgeous color pin-ups literally pasted to the inside covers. If only every comic-book franchise had this kind of quality control.

Comics Time: Boy’s Club #3

September 30, 2009Boy’s Club #3

Matt Furie, writer/artist

Buenaventura Press, 2009

40 pages

$4.95

Buy it from Buenaventura Press

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Savage Critic(s).

Comics Time: Two Panels from SPX 2009

September 28, 2009In lieu of our regularly scheduled Comics Time review, I’m happy to present mp3 recordings of the two panels I participated in at SPX this past weekend.

First up is the Critics’ Roundtable, featuring moderator Bill Kartalopolous, Rob Clough, Sean T. Collins, Gary Groth, Chris Mautner, Joe McCulloch, Tucker Stone, and Douglas Wolk.

And next is The New Action, featuring moderator Sean T. Collins, Frank Santoro, Benjamin Marra, Kazimir Strzepek, and Shawn Cheng.

Enjoy!

Comics Time: Storeyville

September 25, 2009

Storeyville

Frank Santoro, writer/artist

PictureBox, 2007

48 pages, hardcover

$24.95

Buy it for just $15.95 from PictureBox

As dense and rough-hewn as his more recent comics are spacious and delicate, yet some how retaining an easy, breezy, open feel, Storeyville is an object lesson in how to create and maintain an immersive atmosphere in comics. On giant pages stamped with a gutterless 3-by-5 15-panel grid and colored with admirable restraint by the extremely effective Katie Glicksberg, Santoro traces the progress of his protagonist Will through shantytowns, railways, and harbors as he searches for his old friend and mentor Reverend Rudy in order to make amends for some mysterious past transgression. Nearly every panel-sized vista we receive into Will’s journey is a deep-focus wonder, perspective leading us down roads, over fields, through cities, onboard ships, the characters frequently popping against the background like figures in some sort of altcomix View-Master. Realism and impressionism engage in a constant back-and-forth, leading to subtle shifts in your visual and emotional focus during any particular scene as well as reflecting, one assumes, similar shifts for Will himself. The nearest point of visual comparison is Ben Katchor, but while Katchor’s surround-sound POVs and time-faded inkwashes are used in the service of a surrealist magnification of vanished urbanity in which a slightly deranged objectivity is constantly maintained, Santoro’s subjective use of some of the same tools paradoxically gives Storeyville a WYSIWYG tone to it, as though he’s telling it like it is. The reason for this becomes clear when Will and the Reverend finally meet up, and both Will’s supposed crime against his pal and his ensuing need to atone are shrugged off. Consumed with both guilt and a hope that the act of alleviating it will open up a new path for his future, Will couldn’t possibly be an objective observer of his surroundings; his view of himself really did determine his view of the world and his possible place in it. Highly recommended.

Comics Time: “Superhero comics worth your time today”

September 23, 2009Comics Time: Clive Barker’s Seduth

September 21, 2009

Clive Barker’s Seduth

Clive Barker’s Seduth

Clive Barker, Chris Monfette, writers

Gabriel Rodriguez, artist

Ray Zone, “3-D conversion”

IDW, October 2009

32 pages

$5.99

“Surprise”: I love Clive Barker. Actual surprise: I was not looking forward to reading this Clive Barker comic. Despite its being touted as Barker’s first straight-to-comics work in two decades, the presence of a co-writer dampened my enthusiasm. So too did the 3-D aspect–we’ve all been burned by gimmickry. As for IDW’s involvement, I’d been mightily impressed by Kris Oprisko and Gabriel Hernandez’s lovely, lyrical Thief of Always adaptation, but Seduth artist Gabriel Rodriguez’s cartoony art on the company’s Great and Secret Show–admirable though it may have been for committing a full 12 issues to the effort–struck me as project-deflatingly wrong for the work. In my head, I see Barker as his own adapter, whether as filmmaker or painter or drawer; after that, I cut to the Gothy Hellraiser/Tapping the Vein aesthetic of the Epic Comics days, or to an altcomix style like C.F.’s that has never actually been applied to his stuff. Dude’s transgressive; let’s keep him that way.

Rarely have I been as happy to be wrong as I was about Seduth. Story first: Holy smokes, is this dark. It’s as savagely nihilistic as anything Barker’s done since the Books of Blood, or the story of Hellbound: Hellraiser II, which in its potentially apocalyptic nature and certain specific geometrical and extradimensional imagery is perhaps its closest point of comparsion. Heck, Seduth‘s done-in-one short-story nature makes it feel like an adaptation of a lost BoB outtake. But whereas most adaptations belabor the point, ladling unnecessary prose atop redundant illustrations for an oomph-sapping length of time, then suddenly eliding entire sections, this thing just leaps out of the gate and proceeds at an inexorable pace to its hopeless conclusion. If anything, it’s almost too rapid-fire, rather than the usual tedious legato-staccato juxtaposition you’ll find in comics versions of prose writers’ works. And whatever the division of labor between Barker and Monfette, the transitions are seamless, even to this seasoned observer of Barker’s work. After well over a decade of fantasy from the man, not even of the “dark” variety in many cases, I’d all but forgotten he had this kind of thing in him.

Meanwhile, whatever his deviation from my platonic Barker-adpatation ideal, Rodriguez steps up big-time. Yes, his work is cartoony rather than romantic or abstracted, the directions I’d go in, but its cartooniness is rock solid and reminiscent of some of the form’s most skillful current practitioners–some Tony Moore here, some Philip Bond here. Most of all it relies on a thick, confident line, which turns out to be perfectly suited to 3-D. From what I’ve been told, 3-D effects specialist Zone was involved in the project nearly from its conception, consulting with Barker, Monfette, Rodriguez, and project major domo Robb Humphreys on what kind of effects he’d like to employ in a perfect world. Barker appears to have given him carte blanche, because there’s nary a jump-scare “look out, a hand’s reaching out at you and a knife’s flying at your face!” cliche in sight. Instead, it’s all about layering, playing off the congruences and tangents of Rodriguez’s line to draw the eye in and around the page; the effect is dazzlingly unpleasant in all the right ways. Perhaps it’s just all the Chippendale and Rickheit I’ve been reading talking, but it struck me as an extremely effective and, yes, alternative way of exploring space on the page, to the point where I’m now curious to see what a Fort Thunder alum might do with this particular toolkit. But it can be used for spectacle as well, and it is, particularly in one back-to-back splash-page sequence in which Rodriguez, Zone, and colorist Jay Fotos produce an effect reminiscent of Dr. Manhattan’s line about the light taking him to pieces in Watchmen. Barker, who’s been vocally mainlining the work of Grant Morrison, was surely inspired by Morrison’s Final Crisis tie-in Superman Beyond both in the use of 3-D in the first place and its narrative role as a sign of extradimensionality, but I think the special effect is more nuanced, more effective, here.

So three cheers for Seduth; it made a believer out of this skeptic. Barker has long been thwarted by obstacles in terms of getting his ideas out to the public, from a studio sitting on his movie to a publisher rejecting his photography collection as too explicit to his own overflow of ideas getting the better of him to the point where he advances many projects but completes few. Comics famously has one of the lowest idea-to-finished-product thresholds in the arts; here’s hoping he continues to make such good, focused, no-nonsense use of it as he does in this short, sharp shock.

Comics Time: Gangsta Rap Posse #1

September 18, 2009

Gangsta Rap Posse #1

Benjamin Marra, writer/artist

American Tradition, 2009

14 pages

$2

Or: “What If N.W.A. Weren’t Making All That Shit Up?” The idea of a Bush I-era hardcore hip-hop outfit who actually are gun-toting, ho-pimping, mass-murdering drug kingpins as outlined in their platinum-selling rap career is so fucking brilliant a high concept I’m stunned I’ve never seen it in action before. It’s difficult to remember now, in an age when Jay-Z has more number-one album debuts than anyone but the Beatles and the President jokingly banters about Kanye West’s antics, but when my generation of white kids was growing up, “rapper” was a career that took on the same sort of quasi-mystical air as “cowboy” or “ninja.” Obviously there really were people who did those things for a living–okay, maybe not ninjas so much anymore–but the word, the concept, had a totemistic quality above and beyond “performer who composes and recites rhymes over beats.” Now, I was never a huge gangsta fan, but the less criminally minded but equally angry Public Enemy were one of my favorite groups of any kind during middle school, and from Flav’s accessories to Chuck D’s barn-burning baritone to the marching, uniformed S1Ws to that crosshairs logo, P.E. came across like a black G.I. Joe squad. The kinds of hip-hop that politicians and parents groups rent their garments over back then were tailor-made for action-hero status, and that’s what Marra delivers here. Watching his N.W.A. manques roll up on a rival MC’s compound and strafe his bodyguards with machine-gun fire fulfills a long deferred desire to see the larger-than-life lyrics of such groups made real, or at least as real as an action comic would make them.

It’s so effective in that regard that it’s tempting to overlook the obviously problematic racial territory we’re in. What we have here is a white guy taking Easy, Cube, Ren, and Dre’s lurid cop-killing, bitch-fucking, crack-pipe-illuminated fantasy world and drawing it, and that’s a bit of a sticky wicket, innit? It’s an ugly portrait, even if you’re just painting by the numbers left by the subjects. Fortunately, aside from the all-too-real hairstyles of that era, the visual stereotyping is kept to a minimum; Robert Crumb’s “When the Niggers Take Over America” this isn’t. But the irony is that while, to me, Crumb’s comic is an obvious parody of white racism, Gangsta Rap Posse‘s lack of Crumb’s corrosive irony and sarcasm might make it tougher for some to take despite its simultaneous lack of Crumb’s most outre visuals. Similarly, the dialogue’s ebonics are a far cry from Crumb’s pidgin dialect, but it’s also never half as clever, say, the lyrics from Straight Outta Compton, which were so wickedly funny that they came across like the group letting you in on the joke. Here, it’s a little tougher to tell if the joke’s on them.

But it seems to me that what Marra’s doing is simply taking vintage gangsta and treating it like any other kind of genre fiction. Perhaps the big clue is the sequence where the GRP’s manager complains that the record label’s been waiting for their new album for two years–how could they possibly have time to maintain their recording career when they’ve got an organized crime empire to run? The Gangsta Rap Posse doesn’t exist in continuity with Malcolm X or the Last Poets, they’re in the tradition of Robert E. Howard or the film library of Golan and Globus, and Marra’s using “Fuck tha Police” here the same way he used exploitation cinema in Night Business, or maybe even the same way Bryan Lee O’Malley uses Mega Man in Scott Pilgrim. He’s working much, much edgier territory here than either of those works–it has a lot more in common with Johnny Ryan than O’Malley–but you get that same thrill of cross-pollination and unexpected magpie influences. So I’m down. And I’m really hoping the GRP come up against a fictionalized black-nationalist paramilitary organization version of Public Enemy in the next issue.

Comics Time: Night Business #1-2

September 16, 2009

Night Business #1 & 2

Benjamin Marra, writer/artist

American Tradition, 2008-2009

24 pages each

$3 each

Buy them from BenjaminMarra.com

I had a whole long tedious review of these comics written out and five seconds ago I deleted it. Didn’t even copy it to the clipboard first! I think it’s stupid to write a boring review of an exciting comic. (Not that it’s stopped me in the past…) And Night Business is definitely an exciting comic, the kind of thing you want to sneak into the hands of all your teenaged cousins or spill beer and pizza grease on during the Crank 2: High Voltage/Road House/Predator movie marathon you’re having this Friday night.

The point I was trying to make in the scrapped review was that Night Business isn’t a pastiche of ’80s trash-culture thrillers as found in straight-to-video late-night-cable exploitation movies or “adult” independent comics from fly-by-night “publishers” so much as it’s a re-creation of them. Dolly Parton (whom, coincidentally, Marra has drawn) famously said “it costs a lot of money to look this cheap”; while I doubt that Night Business cost anyone a lot of money, its cheapness is clearly hard-earned. Benjamin Marra’s art is studiously amateurish and ugly in a totally consistent fashion–precisely the way that the art of someone whose natural talent is totally outgunned by his boundless enthusiasm and obsession bordering on dedication would be. These blocky, blockheaded, stiff figures–everyone, male and female, looks like their bodies are 85% gristle–seem like the thought-through product of a worldview, like they’re the output of someone who’s drawn page after page after meaty, pulpy page of these people without ever thinking twice about what anyone will think of it (beyond, perhaps, “they’ll fuckin’ love it!”). The layouts are simple, all business, as if to say “enough of all the frou-frou, let’s just see what happens next.” Every outfit is peeled from some hair-metal or porno fantasy world where men are either leather and denim street toughs or sharp-dressed sharks in suits, and where women routinely walk around in lingerie and heels. The City (capitalized like a motherfucker) consists almost solely of strip clubs, alleys, morgues, and the preposterous offices of an exotic-dancer management empire; everything is lit by streetlights or neon. In order to offset some of the icky taste that might be left in your mouth by doing a story about the serial murder of strippers while spending page after page depicting the naked bodies of those strippers (necessarily, I think; look how toothless Robert Rodriguez’s strangely prudish grindhouse homage Planet Terror ended up being without it), the series takes a page from every bard of the urban nightpeople since Steve Perry’s small-town girl took the midnight train going anywhere and builds up the hopes, desires, and dreams of each dancer as she takes it off to the leering crowds. Sure, they’re all pure-dee hokum, but in a world where the men’s emotions can all be expressed by grimacing and never rise above the complexity level of a Blackest Night tie-in issue’s Lantern Corps appearances, they’re the most psychologically fleshed-out characters in the book. The effect isn’t just reminiscent of some bargain-bin Scarface, it’s identical. If it weren’t for the ironic author photo and bio giving the game away at the back of each issue you’d never know that Marra is, on some level at least, kidding. And by that point, who cares? Smoke ’em if you got ’em and bring on issue #3.

Comics Time: The Squirrel Machine

September 14, 2009

The Squirrel Machine

Hans Rickheit, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2009

192 pages, hardcover

$18.99

Given what I’ve been reading lately I can’t help but compare Hans Rickheit to Fort Thunder. Like Brian Chippendale, Mat Brinkman, Brian Ralph et al, Rickheit spent the late ’90s and very early ’00s living and working in a combination art gallery/performance space/flophouse in a New England college town–theirs, Fort Thunder, in Providence; his, the Zeitgeist Gallery, in Cambridge. Like them, he saw his one-time shangri-la end before its time–theirs by municipal diktat, his by fire. Like them–and, like them, perhaps unsurprisingly given his years-long conflation of room and board with bristol board–he creates comics centered on the exploration of space, rooms, houses, environments. And like them, he fills that space with marks, so that reading one is almost a tactile, exploratory experience itself.

But the similarities are not complete. Unlike Ralph’s cavemen or Brinkman’s monsters or Chippendale’s warriors, Rickheit’s Edwardians are observers at least as much as explorers. Though they move about in his strange, gristly world, they are not of that world. More often than not they’re limned by a fine white void; it serves the purpose of making them pop against his often overwhelming backgrounds, yes, but it also reinforces their separateness, their otherness. They wander through strange environments constructed by unknown architects, gazing through lenses and orifices at any number of bizarre transmixtures of human, animal, and machine. They are constantly seeing things, to borrow the title of a book by Rickheit’s visual and thematic kindred spirit Jim Woodring. When we see what they see, the effect is reminiscent of catching a glimpse of an older family member as he or she masturbates, or strips to reveal what Rickehit’s friend E. Stephen Frederick refers to in his memorably Kenneth Smithian introduction to The Squirrel Machine as “secondary hair.”

In the comics of the Fort, exploration is, at worst, value-neutral. In Ralph’s comics they lead mostly to mischief and lessons learned (though that changed somewhat in the bleak zombie comic Daybreak), in Chippendale’s they usually lead to freedom or adventure, and in Brinkman’s, for every bleak wordless parable of creatures lost in an endless maze, there’s another LOL-inducing story of a beast barging into a castle to take a dump on the king’s throne. In Rickheit’s comics, though, the explorations and the visions waiting at their conclusions are unmistakably disturbing. They reveal creatures and creations of arcane origin and dubious value, frequently hidden inside a smoothly artificial or warmly organic surface like a grotesque parody of birth, or a Cracker Jack prize. When you end up at the end of one of Rickheit’s wonderings, there’s a sense that, to quote Trent Reznor, “Now I am somewhere I am not supposed to be, and I can see things I know I really shouldn’t see.” That’s no less true for our desire to see them. In this, he has more in common with Josh Simmons than with the Fort, though unlike the House author, up until this point the damage incurred in Rickheit’s characters’ travels is more psychological than physical.

This changes in The Squirrel Machine, Rickheit’s Fantagraphics debut and for all intents and purposes a simultaneous coming-out party and summation of all that has gone before. In the past–his Xeric-winning erotic coming-of-age nightmare Chloe, his dewily sexualized surrealist gag strip Cochlea & Eustacea–Rickheit imbued his character’s journeys into what he refers to as the Underbrain with a sliver of redemptive power. Chloe finds something that replaces what she lost; Cochlea and Eustacea’s antics are as funny and horny as they are freaky. But here, the downbeat direction hinted at by C&E’s fate in the last issue of Rickheit’s self-published anthology Chrome Fetus emerges in full flower, and the result is awesome to behold.

In Rickheit’s story of the brilliant brothers Torpor, William and Edmund, art does not provide the antidote to the encroaching cruelty of the civilized world, as it does in Chippendale’s Ninja. On the contrary, the art of William and Edmund is wholly dependent on the taking of life. Their childhood games aren’t free-spirited enactments of the struggle of good against evil, and they’re not really games, either. They’re attempts to follow their brains as far as they can take them. Other beings–the animals who are their chosen medium, their hapless mother, the angry townsfolk and mocking bullies–factor in only as means rather than ends. Even exploration itself is represented as a frightening loss of control by its most prominent exponent here, Edmund’s sleepwalking. There seems to be no escape from the power structure of oppressor and oppressed.

The one exception to that rule is for those with whom they can form a sexual connection–but even that will only be allowed to take them so far. Visually, Rickheit tips his hand after the book’s first big sex scene. It’s weird, hot stuff as always from Rickheit, rooted in memorable details that serve to knock you off balance and make you vulnerable like the characters themselves. But in the middle of the act we cut to a stunning two-page spread, silent, no people present–simply incredibly byzantine images of the Torpor family home, utterly cluttered with the detritus of their inventions. Pipes and chains and ropes and stairs and beams and wires crisscross the panels, creating along with the gutters a dense thicket of tangents and congruences. The eye is led everywhere and nowhere all at once. The message is clear: Sex offers no escape. And like art, it can, and likely will, destroy and degrade and subjugate. When life and love, of a sort, finally do reassert themselves at the book’s end, it’s horrifying and drawn in a fashion that makes it look less like a natural thing and more like a terrible apparition, or a special effect.

It’s strange, but of all the dizzying details Rickheit deploys in The Squirrel Machine, the one that stood out the most to me came early on in the book: A distant water tower topped not with the usual tank, but with what looks like a giant version of the old-fashioned, grated helmets divers once wore. It sits atop a tower and beside a train trestle that are both as realistic as you please, but there it is, a mute monument to illogic. In Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, Amadeus Arkham recalls his fateful initiation into his mad mother’s “other world”:

A world of fathomless signs and portents. Of magic and terror. And mysterious symbols.

This has long been the world Rickheit has chronicled. The allure in both cases is that these portents can be scryed, these symbols can be decoded, this world can be mapped. But it’s only in reading this book–a painstaking chronicle of the lack of solace provided by art to the powerless–and thinking back on the diver’s-helmet tower that I realized that in our darkest moments, it’s easy to see that world as our world too–only the symbols can’t be read. When exploration is punished, when everything we see feels like something we oughtn’t, when theoretically life-affirming forces are either nipped in the bud or exposed as brutal frauds, doesn’t it all seem as maddeningly inscrutable as a giant diver’s helmet on top of a water tower? That there’s some reason for it all, something lurking beneath the surface, something we will never, ever get to?

Comics Time: Ninja

September 11, 2009

Ninja

Brian Chippendale, writer/artist

PictureBox, 2006

128 pages, hardcover

$34.95

Starting off a review of a Brian Chippendale comic by talking a plot seems like the laziest most wrongheaded way to start off a review of a Brian Chippendale comic, like an unwitting parody of all the lame comics criticism that other comics critics criticize for focusing on writing rather than art. Shouldn’t I be saying something about markmaking or snake-style layouts? Maybe, but much more so than with Chippendale’s Maggots, the creation of which predated and the publication of which followed this book, the plot of Ninja matters. Not just as a driver for the imagery, but to Chippendale, and to me.

The book starts with these silly little comics about a ninja–basically, fighting against Cobra from GI Joe–that Chippendale drew when he was 11. They look like a child artist’s representation of a sidescrolling Nintendo game, like Ninja Gaiden: After breaking into a bad-guy base, the ninja will move forward or up or down and discover a new opponent, and we watch as he figures out a way to defeat or avoid each enemy. Most of these strips end when the ninja, having stolen some valuables from the evildoers, successfully escapes from their lair and returns to his home (complete with its incongruously normal front door). What Chippendale does in this collection is every so often insert a brand-new, recently drawn strip between the stuff he drew as a kid, fleshing out the Ninja’s home life and world at large. Meanwhile, in the world of the kid strips, the bad guys become less involved with…whatever it was they were up to before the Ninja showed up, and more and more fixated on capturing and killing the Ninja in retribution for all the havoc he’s caused them.

The problem for Chippendale is that his younger self was apparently less dedicated to making art than his grown-up incarnation–like many kids who spent their youths creating their own, enthusiastically derivative fantasy worlds to play in, he eventually ran out of steam, and his final Ninja strip from that era is unfinished. The solution? A new penultimate strip, in which the bad guys build a doomsday device that gets out of control and begins absorbing reality as we know it. Now, when 11-year-old Chippendale’s last Ninja strip abruptly cuts off mid-page, leaving rows of blank panels unfilled beneath it, it’s not just a kid losing interest and putting his pencil down to go play Nintendo or skateboard–it’s the end of a world as we know it.

Cut to 18 years later, and to the bulk of the book. Now, in typical Fort Thunder fashion (prefigured to an astonishing degree by the space-based action of the kid stuff) we explore the city of Grain and its surroundings, where the Ninja and his enemies once lived. Only now, with the Ninja gone and his “killing villains for fun and profit” activities curtailed, the city’s gone to hell. Not the openly dictatorial hell that the old Bad Guys might have ushered in–they seem to have been consumed by their own device, unless I missed something–but a quotidian nightmare of corrupt public officials, rapacious corporate raiders, callous resource thieves, brutal cops, and relentless, even violent, gentrification and homogenization. Everyone may still look like refugees from Super Mario or the Masters of the Universe, and the level of violence and dimension-hopping and overall weirdness remains consistent with that, but in essence their concerns are the same as those of an artist who returns home from a tour with his noise-rock band to discover the place he’d lived and worked in for years had chains on the doors so the city could raze it and install a supermarket parking lot.

Of course none of this is super-apparent from the get-go. I spent a decent amount of time waiting for the Ninja to show up again after the 18-year jump, storming back into town to take it back. But as we watch Chippendale’s little groups of characters–good, bad, and ugly alike–go about their zany business, it becomes apparent that there’s a build to the eventual reveal of “What happened to the Ninja?” to rival any slow-burn mystery-villain storyline Marvel or DC have done this decade. And once you find out, the solution is elegantly simple, childlike, charming, and utterly inspiring. I’m not going to spoil it, but suffice it to say I closed this book feeling better about humanity than I’ve felt in quite some time. Maybe there is a solution after all.

Okay, so, the art. The collage material is an eye-candy orgy as you’d expect, one of the purest distillations of that aspect of Chippendale and the whole Providence scene’s output as I’ve seen so far, though for the life of me I couldn’t figure out what role it was playing in the narrative–it didn’t seem to pop up at logical reality-warping breaks, like when the Bad Guys’ machine ran amok and caused a House of M style fade to white–until I read in PictureBox’s synopsis of the book that they’re just chapter breaks. More immediately grokkable and impressive to me were the many, many bravura moments in the comics themselves–painstakingly delineated Dore-style deserts, a city covered completely in OCD stripes, characters becoming aware of a spy camera filming them in a scene simultaneously “shot” from their perspective and that of the camera, two scenes taking place at the same time but on different vibrational planes suddenly smooshed together in strips as though they were pieced together from two separate shredded documents, a brutal torture sequence and hot sex scene both showing up in the book’s final act. And Chippendales back-and-forth panel flow is so addictive (and much more consistent than in Maggots) that I found myself trying to read other comics that way after finishing Ninja. There’s a certain magic to these elements that feeds into and plays off of the narrative even when it doesn’t have any strict narrative cause, like any great spectacle.

But ultimately this is a book about an idea: the need to persevere in your pursuit of fun, which in most of the ways that matter is a synonym for Good with a capital g. Sometimes, compromise may be necessary–after all, the Ninja was slicing up bad guys not just because in the world of the comic it’s the right thing to do, but for their loot; and (still trying to avoid being spoilery, though this may skirt the edge) his ultimate fate does not necessarily provide a happy ending for everyone. But you can reclaim the comics you made when you were a kid and build them up into a statement on where you are as a grown-up without sacrificing the buoyant illogic and unfettered imagination that came through originally. You can hang on to the important things you found in your arts-commune idyll even when the outside world finally smashes down the walls around you. You can still think ninjas are cool.

Comics Time: Sweet Tooth #1

September 9, 2009

Sweet Tooth #1

Jeff Lemire, writer/artist

DC/Vertigo, September 2009

32 pages

$1.00!

Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim of Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job! have a recurring…concept, I guess? called “Brown Town.” Sometimes it’s used as a euphemism for potty humor: “That ‘Poop Tube’ sketch was a little too Brown Town for our parents.” Sometimes it’s just a funny-sounding nonsense phrase, as in their unsolicited candy jingle-cum-Doobie Brothers pastiche “Rolo Tony.” But I like to think it’s meant to describe where we’re often taken by colorists for Vertigo comics.

Jose Villarrubia’s Lee Loughridge impersonation aside, this is a fascinating little comic just because of how different it is from pretty much everything else Vertigo has done this decade. There’s no fabulous and violent rock’n’rollin’, there’s no in-your-face ugliness (except for one shot–pun intended), there’s no modern-mythmaking, no real echoes of Gaiman or Ennis or Ellis or Azzarello or Willigham. And there’s no writer/artist team, either–it’s just Jeff Lemire, author of Top Shelf’s Essex County trilogy and creator of some of the best damn convention sketches you will ever see. It’s tough to imagine a better fit for this story of an isolated deer-boy hybrid left on his own in an unforgiving post-apocalyptic world after the death of his father than Lemire’s shaky, nervous line, which has always had a vulnerable deer-in-the-headlights quality and which isn’t toned down or slicked up a bit for this major-label effort. Even the bloodspatter remains an abstracted splash of red rather than an HBO Original gorefest. The art holds color well, moreover, though as I said, it might be nice if colors other than brown were deployed for that purpose. Instant-classic cover, too, perhaps the best the imprint has seen…I was gonna say since Dave Johnson on 100 Bullets or James Jean on Fables, but this strikes me as potentially iconic in and of itself in a way that those storied cover-art runs only were in toto.

In one of those self-promoting editorial columns Vertigo creators do during a series launch, Lemire suggests that what sets Sweet Tooth apart from your average monthly comic is the quietness of his approach, an approach he’s carrying over from his altcomix, the idea being that when something really fucked up happens, it’ll be that much more startling. I think he’s right, so far, one issue in. Now, there are things I’m not so sure about–the boy’s dialect scans a bit like Claremontian cliche at times, while his bumpkin naivete and the hunters’ gruff bad-guy-ness are a little too high-pitched to maintain that delicate quietness Lemire’s striving for. And this is a bit picayune, but I feel like a lot of shots crop off the characters’ feet for no reason? But regardless, this is a very likeable book, a comic you want to succeed really for all the right reasons: It’s clearly the product of a personal vision rather than an attempt to fill some kind of niche, it has lovely art, it attempts to win you over to its characters rather than bash you over the head with their badassness, and it honestly seems like it could go anyplace at all at this point. I’ll be following it.