Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

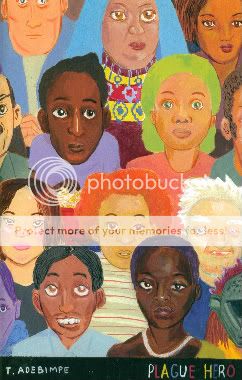

Comics Time: Crossing the Empty Quarter and Other Stories

January 22, 2010

Crossing the Empty Quarter and Other Stories

Carol Swain, writer/artist

Dark Horse, December 2009

200 pages, hardcover

$24.95

Carol Swain’s panels are like prisons. They feel too narrow, too cramped for her dramatic angles, her furiously filled-in blacks and grays, her askew, sometimes even fish-eyed perspective, and her disorienting character close-ups. Thus they root you in this moment, then this one, then this one, force you to confront it head-on–often literally, bringing you right up against the face of the protagonist in each of this anthology’s thirty-plus short stories. Which is fitting, since they too are often rooted or even trapped themselves. Some are hemmed in by the metaphysical constructs of Swain’s daydreams or gentle magic-realist conceits–immovably knee-deep in the mud of the Atlantic, chained in the bedroom by overprotective parents who alternately rattle off the dangers of the outside world and the many knitting projects she could do inside, sealed in the black glass of fused sand created by a bomb blast in the desert, trapped in the middle of nowhere by faulty compasses and starless skies. Others are stuck in more quotidian predicaments–an immigrant’s plight, soft vote suppression, lots and lots of dead-end towns, lots and lots of dull grinding urban grayness, lots and lots of glimpses of a larger world that seem only to reinforce the futility of reaching further and higher. And yet, there’s always that lovely, lush shading and linework, a hint of softness, and with it a suggestion that maybe there’s reason to hope. I think that makes the book harder on you, ultimately. In hopelessness there’s release.

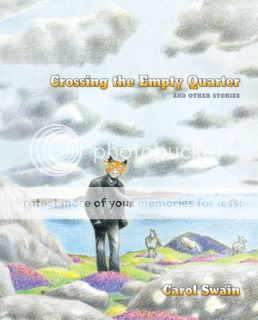

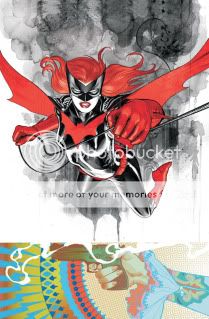

Comics Time: Detective Comics #854-860

January 20, 2010

Detective Comics #854-860

Greg Rucka, writer

J.H. Williams III, artist

DC, 2009-2010

24 story pages each

$3.99 each

I’ll admit it, I was too hard on Detective Comics. I always understood, and agreed with, every word of praise offered for J.H. Williams III’s almost comically proficient art, mind you. You don’t need me to go over that, Jog handled it nicely. It’s just that beyond the art…well, I didn’t think there was anything beyond the art.

Maybe it’s that Question back-up that threw me, with the erstwhile Renee Montoya adopting the exact same crimefighting set-up as the lead feature’s star, i.e. beautiful lesbian with military and/or law-enforcement training adopts the mantle of a male superhero while her old-man sidekick sits at a computer back at HQ. And it’s not exactly as if either of them are the only strong-women-also-cry tough gals Rucka’s ever written. Meanwhile, some past Rucka plot points I never really got into come along for the ride, most prominently the convoluted Religion of Crime and its Batwoman-obsessed prophecies. I liked that idea when it was tied directly into Darkseid–the more other stuff that it hooked up with, from Vandal Savage to some old Rucka characters to the actual Bible, the less compelling I found it.

On a more fundamental level I think I’m just a lot less interested in superhero comics as fed through the filter of writers who’ve read, watched, and written a lot of spy and crime fiction over the past decade. What was once a thrilling deviation–seriously, The Ultimates, Sleeper, Gotham Central and the Daredevil/Alias/Powers trifecta blew my mind once upon a time–is now the default. Over at Marvel you’re seeing, or you will be seeing, I think, that noir/black-ops framework give way to a bold new era defined by loosey-goosier writers like Matt Fraction and Jonathan Hickman; Ed Brubaker’s given a pass because that really is the perfect place for a postmillennial Captain America to be. At DC, that kind of stuff doesn’t interest the main moneymakers and ship-steerers, Geoff Johns and Grant Morrison, in the slightest. And though I’m far less militant (heh) about this point than other readers I know, there’s always the suspicion that shoehorning superheroes and their fantastical fiction into exciting but reality-based counterpart activities like law enforcement and espionage and organized crime is a way to strip them of the weirdness and wonder even the worst of them usually contain–to polish them up even while darkening them up, to smooth out the angles and make them action-franchise-friendly. So for all those reasons there’s a degree to which I’ve had my fill of books in which characters nonchalantly drop military argot in conversation and suchlike, and thus I’m a tough nut for Rucka’s writing in ‘Tec to crack.

But after taking the opportunity to read all seven issues of the “Batwoman in Detective Comics” run, I’ve realized just how far short I was selling it. Is the story a game-changer, a brain-melter? No. But it’s a good deal wilder and weirder and, yes, more wondrous than your average spandex-turned-kevlar effort. And shame on me for not seeing how Williams’s art, far from an Avatar-style silk hat on a pig, draws on and enhances Rucka’s strongest stuff while muting the weaker elements. Simply put, how did I miss how very Hot Topic the whole “pale redheaded lesbian dresses up like an S&M vampire and does battle with her pale loligoth Satan-worshipping evil twin sister who dresses like Alice in Wonderland” thing is? It’s a very glam, very goth, very fetishy, very fun set-up, hammered home with Williams’s dark psychedelia, polymorphous mimickry (that extended Mazzucchelli impersonation is really breathtaking) and (you don’t hear much about this, but for real) dazzling good-girl art.

What’s more, this is actually some of my favorite Rucka writing I’ve come across. You know how most superheroes have a two-stage origin? Batman’s parents are killed, and the bat flies through his window; Spider-Man gets bitten by the spider, and his Uncle gets killed; Superman’s home planet blows up, and he’s raised in all-American fashion by his kindly adoptive parents? Batwoman’s mother and sister are killed, and then she gets Don’t Ask Don’t Tell’d out of the military. She’s not just gay–homophobia is a foundational trauma for her. I love it. I also really like the air of doomed glamour, to use a favorite phrase of mine of late, with which Rucka imbues the whole affair. Batwoman’s bright-red trimmings seem like war paint she puts on to power past the sense that this was all a terrible, terrible idea. Rucka knows the power of pointed silences and fade-outs, all of which are painstakingly choreographed by Williams, using disembodied panel boxes to pinpoint moments in the comics equivalent of slow motion. When we suddenly see Alice’s tear-streaked mascara emphasized during her fight with Batwoman’s father, when Alice falls across the top and down the right hand side of a climactic spread with a great gulf of ocean mutely occupying the rest of the pages–it means something. I can already hear the Moore-derived derision that none of this has any echo in any one’s real life, but even if that’s true, who cares? It’s violent, it’s sexy, it’s spectacular–just what I want from my superhero comics.

Comics Time: Forming

January 18, 2010

Forming

Jesse Moynihan, writer/artist

ongoing webcomic, January 2009-January 2010 (and counting)

I was pretty happy with the high concept I came up with for Afrodisiac, so let’s try it again: What if the stars of Anders Nilsen’s Big Questions were the Big Answers? Like Nilsen’s funny-animal epic, Forming tells the tale of characters struggling with the stuff of existence–life, death, fate, their place in a universe that appears fundamentally capricious. Unlike Nilsen’s birds, though, Moynihan’s characters are archangels, cosmically powered alien beings, demigods and titans of legend, founding members of humanity who commune (and copulate) with higher beings on a daily basis. The metaphor scales our human plight up, not down, in other words. The art follows suit. Moynihan’s line is soft, its weight gently fluctuating, shored up by quietly irregular coloring, suggesting the same vulnerabilities as Nilsen’s stippling and figurework. But the design is maximalist: Crazy Kirbyesque costumes, Fletcher Hanks psychedelic action, long sequences of physical combat, extradimensional travel, mental fantasias. The stakes are similarly higher–the central action includes Lucifer’s battle with Michael and the birth of human civilization as conferred upon us by ancient astronauts. The gag, of course, is that these highfalutin’ types are just as messed up as we are, complaining about their jobs and their family and their sex lives and so on.

So yeah, you’ve seen it before. But what makes its use in Forming so appealing is the strip’s rolling, loping, laconic pace. New subplots–a literal clash of the titans, Lucifer & Michael, Adam & Eve, corporate intrigue on the alien homeworld–are slowly folded into the strip, and our lens on the action swings back and forth between them like a pendulum. Moreover, most of the strip’s two-page installments are stacked on top of each other, our eyes slowly cascading downward as the action unfolds over a long vertical plane. The cumulative effect does even more than the specifics of the dialogue in terms of humanizing the cosmic characters and wringing bleak gallows humor from their dilemmas. If this thing ever gets collected in print, I’d love to see it in a super-tall, super-narrow format just for that reason. It’s a very pleasurable reading experience, and it’s easy to see how rewarding a weekly visit could be.

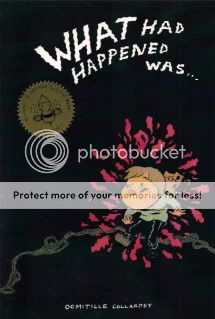

Comics Time: What Had Happened Was…

January 15, 2010

What Had Happened Was…

Domitille Collardey, writer/artist

Weeping Willow, 2009

20 pages

$6

Buy it from Domatille Collardey

You could rough this one up pretty bad if you wanted–like Jog says, it’s an alternative comic of the “here’s some stuff that happened” school that people who dislike alternative comics think all alternative comics attend. Collardey’s stories–actually, that’s too strong a word–reminiscences about her move to Brooklyn, her visit to San Francisco, her interview with Francoise Mouly, her conversation with her Holocaust-survivor grandfather, even her very life story aren’t revelatory, or (with one obvious aforementioned exception) even memorable on their own terms. What they are is a showcase for her art, and she’s got some serious chops. I’m really drawn to her wavy line, the way a series of gentle S-curves both cohere into little people and convey the timidity and uncertainty with which Collardey apparently approaches the world. Against that backdrop her depiction of Mouly really pops: Bigger eyes rimmed with make-up, darker hair, taller body, confidence and competence standing out amid Collardey’s gee-shucks artistic personality. Equally impressive are color sequences that employ brown and gray watercolors to convey warmth rather than desolation or “realism,” most notably in a self-portait that strikes me as both clear-eyed and flattering–which is then surrounded by a colorful panoply of cartoon heads. The paper stock really holds Collardey’s brushwork and colors well, by the way. As a sampler of an artist with a lot of potential, it’s worth a glimpse. Let’s see where she goes from here.

Comics Time: Afrodisiac

January 13, 2010

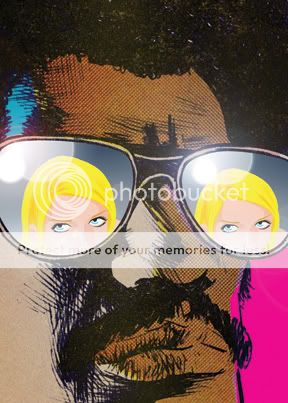

Afrodisiac

Jim Rugg & Brian Maruca, writers

Jim Rugg, artist

AdHouse, January 2010

96 pages, hardcover

$14.95

What If Pim & Francie Got Bitten by a Radioactive Luke Cage? Afrodisiac, like Al Columbia’s fractured masterpiece, is a comic, an art book, an objet d’art, an assemblage of stories and story fragments and illustrations and pastiches and sketches and ephemera and so on. Yet I’m guess everyone interested in an Afrodisiac book would have been perfectly happy with an anthology of straightforward blaxploitation riffs, showcasing the heavy-lidded, angular action characters, juicy design choices (this thing is like sound-effect lettering porn), and deadpan over-the-topness we saw from the Rugg & Maruca team in Street Angel, maybe with a few ben-day-dot nods in the direction of faux vintage. So why go further? Well, for one thing, if you have the design talent that Rugg and Chris Pitzer do, why not.

But what these moves communicate is the slipperiness of what Afrodisiac really is. The titular hero receives a different origin with each story–he’s a cyborg, an inner-city Billy Batson, a ghetto Captain America or Thor or Spider-Man. He’s marched through a variety of comic-genre parodies–Archie, romance, funny-animal, Bronze Age Marvel magazines, Bronze Age Marvel comics. Sometimes his adventures are made to look like they could have sprung straight from the ’70s, but other times the coloring or the printing or the language (this ain’t Comic Code approved!) tip the project’s hand. And that’s to say nothing of Rugg’s art, which is sly and slick in a fashion that befits a guy who gets into the annual Society of Illustrators show every year rather than a member of the Gerry Conway-era bullpen. And have we ever lived in a world where a character like the Afrodisiac would get a toy line or a Saturday morning cartoon?

It could have simply coasted on the asskicking concept of a superhero pimp called the Afrodisiac, but every choice Rugg, Maruca, and Pitzer make here makes it harder to put your finger on what’s going on. Which, I think, is the point: Afrodisiac is an attempt by modern white nerds to capture and critique the art made by the white nerds of yesteryear’s attempts to capture the art made for that era’s black audiences in response to what that era’s white entertainment industry thought of that era’s black audiences, specifically what they wanted to see from the relationship between black criminals and white women. (Phew.) It is, in other words, about the nature of truth, about different marginal or marginalized subculture’s attempts to understand and interact with one another, how those attempts magnify and distort one another, and in the end produce art as fascinating and fractured and entertaining and incomplete as the cut-up “final issue” that ends the collection. Powerful stuff? You’re damn right.

Comics Time: Sleeper Car

January 11, 2010

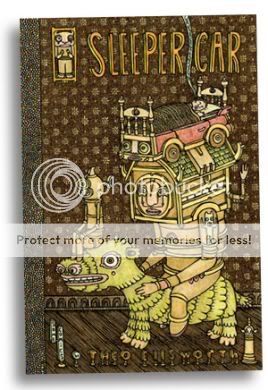

Sleeper Car

Theo Ellsworth, writer/artist

Secret Acres, 2009

32 pages

$6

Theo Ellsworth’s Capacity, a monumental work of ferocious interiority combined with irresistible openness, was one of the decade’s best comic debuts. It was a knockout. Sleeper Car is more like a playful tweak of the nose or pat on the buttcheek. Stepping away from the artistic-autobiography subgenre that made Capacity so singular, Ellsworth uses this 32-page pamphlet as an opportunity to deploy the same tools he used there–the endlessly inventive character designs, the googly eyes and rubber lips, the enveloping crosshatched backgrounds, the seemingly infinite fur and feathers and scales and joints and so on–in the service of what I think could best be called flights of fancy. The stories and strips here are funny, though they’re not out and out gag comics; they’re fantastical, though they’re too loose and unconcerned with narrative worldbuilding to qualify as fantasy. What’s interesting to me is seeing the different approaches he takes with each one.

For example, the longest, central story, about two verbosely formal robots who make a bet about the existence of gnomes, uses a staid six-panel grid to heighten its deadpan humor. But the source of that humor shifts throughout–first it revolves around the wordplay of the droids’ creaky way of speaking, then gets goofy showing the second robot passing the time as the first embarks on his search for proof, then there’s a series of very funny “photos” of the victorious robot’s shenanigans with the loser’s forfeited arm, and then there’s a punchline splash page (!) that injects a whole new comical menace into the proceedings. Throughout, it’s all about knowing just what image will nail the required effect. You see this in many of the strips here: A traveler’s wanderlust depicted by showing him distraught and on skis at the top of his staircase, say, or a sleeping behemoth scratching his head in wonderment as an explorer rockets out of his gullet, or a kid’s eyes peering from the distended neckhole of his pajama shirt as he wraps up his knees, feet, and arms in it to form a “pajama tent,” or a drawing of empty bus stop letting us down easy after a strip in which a traveler’s face transformed wildly from panel to panel. None of it’s gonna bowl you over, but none of it’s meant to. It’s expert, effective cartooning–little sketches of where a cartoonist with this visual vocabulary and this set of ideas can go. I’ll follow him there, that’s for sure.

Comics Time: Monsters

January 8, 2010

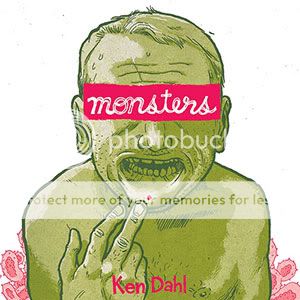

Monsters

Ken Dahl, writer/artist

Secret Acres, 2009

208 pages

$18

Gross-out sex-life autobiography has a storied history in alternative comics, but it’s sort of a St. Olaf story. (Crumb is repeated first as tragedy, than as farce.) Folks with sufficient cartooning chops are afforded ample opportunity to Tex Avery themselves out, which I do appreciate. And of course there’s the thrill we get from coming across someone with no internal censor–to paraphrase Hesh Rabkin, between their brain and their pen, they have no interlocutor. But it’s very, very, very well-trod territory, and you can count me among the people who came across Joe Matt’s Spent and thought “Well, that’s enough of that.”

So it took some persuading for me to give Ken Dahl’s Monsters the story of his life with herpes, a shot. Another comic about some creepy artist type’s loathsome behavior around and toward women? Drawn with confrontationally ugly underground-style depictions of everyone involved and hyperactive exclamation-point-ridden lettering? Coupled with enough grand-guignol lesion close-ups to trigger my skin-growth phobia like wo?

Wrong wrong wrong! I enjoyed the heck out of this book. For starters, I was giving Dahl’s art short shrift. Jeepers this guy is accomplished. I don’t point this out nearly often enough, but as a non-artist, I really get a thrill out of good cartooning because it’s so beyond my ken. To develop a visual vocabulary and deploy it consistently page after page…I mean, man. Anyway, on the most basic level, Dahl’s bobble-headed, adenoidal characters are crafted with an assured, flowing line that trails off into feathering wisps for a hint of vulnerability beneath the slickness. Moreover, they are an instant visual signature, serving both to deflate the angst and self-absorption of his story and satirically skewer the various alt lifestyles of which he is a tangential part. (For what it’s worth, I think the mockery–of everyone from Christians to vegans–is one of the less considered parts of the book, but still, no one comes out of this looking like an angel.) But more importantly for the book, they’re a template from which he can deviate for extravagant, almost Tom Neely-esque sequences, in which Dahl’s emotions and/or his infection literally explode from within and take over in monstrous fashion.

But for me, the most interesting thing about Monsters is Dahl himself. Turns out he’s not a creep at all! He has no idea how he got herpes, had no idea he had it when he gave it to his girlfriend, and commits a grand total of one genuinely douchebaggish actions in the entire course of the book. Instead, he obsesses on his condition to a psychologically debilitating degree, sealing himself off from having a healthy social life or any kind of romantic relationship for years. In fact, while the “educational filmstrip” facts’n’figures sequence about herpes simplex is the book’s ostensible centerpiece, for me the real tour de force was the ending, which in a quick one-two punch upends what I’d thought was going on with both the story’s plot and its moral. Dahl turns out to be far more victim than victimizer, and the deft way in which he teases that reversal out of our expectations for a book of this sort is its best trick.

Comics Time: Giraffes in My Hair: A Rock ‘n’ Roll Life

January 6, 2010

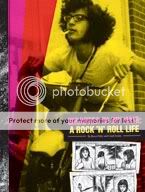

Giraffes in My Hair: A Rock ‘n’ Roll Life

Bruce Paley, writer

Carol Swain, artist

Fantagraphics, 2009

136 pages, hardcover

$19.99

Pencil is not an easy medium to publish in for a cartoonist–just ask the superhero artists whose work looks like the proverbial cake left out in the rain when “digitally inked” or colored right off the original pencils. But Carol Swain makes it look easy, and I think it’s because she’s figured out a way to spot blacks with a pencil. Those sooty shadows and clouds and night skies and manes of wild hair suffuse her work in Giraffes in My Hair with a sort of negative-image glow, popping her foregrounded figures off the page with a barely-there white aura. Couple it with her ever-shifting angles and it’s a damned effective way to create a sense of space and depth, reminiscent of similarly adroit strategies by Jeffrey Brown and Ben Katchor. If Swain’s jarring close-ups make her panels less immersive than theirs, her porous gray shadings make up for it with atmosphere–an inviting softness, tinged with just enough smokiness to remind us that what’s going on here isn’t entirely pleasant. The overall effect works so well that I really had to stop myself and peer at her pages to figure out what made them tick. I was too busy being propelled along by the effortlessness of the art.

So Giraffes, a collection of anecdotes from Bruce Paley’s teens and twenties on America’s countercultural fringe, is a breezy read. But it’s one rooted in an almost unchanging nine-panel grid with sparse, nearly monotone narration. At times this allows the comics to tip over into bluntness, particularly with the ending to some of the stories: The tale of how Paley avoided Vietnam ends with a shot of the Wall; a story of New York City’s ’70s heroin scene ends with Death itself offering us a bag of smack. But in general, the art and the writing are a perfect fit. Swain’s art rarely calls attention to or gets in the way of itself, and in that it meshes seamlessly with Paley’s deadpan “here’s what happened” narrative style, his reluctance to overstate or oversell the import of the anecdote reminiscent of Harvey Pekar’s. (Of course, Pekar’s work rises and falls on the strength of his collaborators–Paley’s got Swain, so there’s not much falling to do here.)

Yet at the same time the presence of that subtitle indicates a unifying theme, which makes Paley’s storytelling choices all the more interesting. The first story shows an 18-year-old Paley ditching college and leaving home to hitchhike cross-country with his girlfriend, but the home life that led him to drop everything and drop out is relegated to a quick line of dialogue and about half a page upon his return from the journey. As hippies give way to punks we suddenly discover that Paley’s a habitual heroin user, but we never see his introduction to the drug. A story about an ill-fated attempt to import drugs from overseas sees Paley casually mention time spent in Tangiers, but up until that point his adventures had been strictly domestic. In some graphic memoirs these lacunae would be maddening; here’s they’re sort of the point.

Paley’s not claiming anything spectacular about the life he lived or the stories he plucked from it. The way he tells it and Swain draws it, living on the edge feels like an interchangeable commodity with Pekar’s life as a civil servant. An interesting conversation with the janitor may be replaced by doing speedballs with Johnny Thunders, but the game’s the same: get by, find a little happiness when you can, and cling to the stories that comprise your life, the recounting of which has a value all its own.

Comics Time: Big Questions #13: A House That Floats

January 4, 2010

Big Questions #13: A House That Floats

Anders Nilsen, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, 2009

44 pages

$9.95

My sincere hope is that a couple years from now the collected Big Questions will lodge itself at the top of future Best of the Decade lists on the strength of material largely published the previous decade, like Jimmy Corrigan and Black Hole before it. Certainly Nilsen is a capital-M Major Talent, a real world-beater for his generation, but the book by which he will be defined has not yet been released. The two Monologues for… books from Fantagraphics delight me with their weird existentialist stick-figure stand-up comedy, but talk about an aquired taste. Dogs and Water might pick up steam in the post-The Road world, but it’s always gonna read grim, and its strange release pattern–first as the fattest stapled pamphlet you ever saw, then a slightly revamped version in hardcover–threw folks for a loop. Don’t Go Where I Can’t Follow devastates virtually anyone who reads it, but its hodgepodge hybrid format, arising from its tragic origin as a travelogue-turned-eulogy, makes it a tough item to classify. The End could end up topping my personal Best of the Decade list, but it’s a one-shot Ignatz-format pamphlet. I could see his mythological comics for Kramers Ergot clicking but there’s just not enough of them.

But soon, along will come a thick hardcover of this monumental series, tracing its evolution from xeroxed minicomics sold at a table alongside Jeffrey Brown, John Hankiewicz, and Paul Hornschemeier comics, through its adoption by D&Q, into its status as one of the only regularly released alternative serials in North America. It’s as fragile and frightening as any of Nilsen’s many, many comics about the baffling horror of senseless death, but it’s also a funny-animal book stuffed with subplots and side-stories and borderline gag strips about wisecracking birds. It works as a showcase of pure cartooning as well as even Nilsen’s most abstract, “pure comics” stuff from MOME or The End, but in the service of a sad and searing realism whose beauty is apparent to any reader even remotely open to altcomics work–certainly I’d stack this issue’s cockpit sequence against anything else this year for sheer stunning loveliness. It functions as allegory, but then turns around and acknowledges its own allegorical nature, and ads enough detail and twists to hold up as a real-deal semi-adventure. It manages to capture and cry for the world’s cruelty, yet hold alive the hope offered by cooperation and community and small kindnesses, even those arising from bare enlightened self-interest, as well as anything this side of Deadwood. I laughed, I cried, in the space of this issue alone. Big Questions is a great comic.

Comics Time: Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka Vols. 1-3

January 1, 2010

Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka Vols. 1-3

Naoki Urasawa, writer/artist

Takashi Nagasaki, writer

Based on Astro Boy: The Greatest Robot on Earth by Osamu Tezuka

Viz, 2009

200 pages each

$12.99 each

I take back everything I said about Naoki Urasawa. Well, okay, no I don’t, but everything I said about Naoki Urasawa definitely does not apply here. Finally, one of his series contains visual elements that exist for more than simply conveying the information of the story as clearly and dramatically as possible. And I didn’t think that was in the offing, by the way, since in the first few pages you get a “guy with a gun turns a corner, does a half-turn and whips the gun at the camera” sequence that struck me as an unimaginative, un-comicsy rip from the cinema. But a few pages later our straight-laced, sad robot detective Gesicht informs a robot-maid wife that her robot-cop husband has been killed in the line of duty, and Urasawa gives us a series of close-ups of the grief-stricken robot’s machine face, which, of course, never changes. And blam, I was hooked.

In Pluto, a contemporary-superhero-comics-style “reimagining” of a classic < i>Astro Boy story by Osamu Tezuka, Urasawa uses the presence of robots as embodiments of surrealism. From the bereaved wife’s static expression, to the towering North No. 2 in his judge’s robe, to sinister Brau 1589’s mangled scrap heap of a body, to a revamp of Astro Boy (aka Atom) that makes him less like a jaunty short-pantsed slugger and more like an eerie kid out of The Shining, they’re the flourish of Weird, the touches of visual poetry, that I always wanted from my limited experience with Urasawa’s work. That his line and design sensibility is otherwise such a just-the-facts affair only heightens their “thing that should not be” effect.

And they seem to have unleashed more where that came from. The series of murders that are the series’ central mystery are themselves like staged art installations, sort of like the theory that holds the Black Dahlia’s murder as a macabre Surrealist masterpiece. Elsewhere, jagged black lines emerge from transmission static as a literal representation of despair; a huge black thing slouches half-unseen through the smoke and sand of a war-ravaged Persian town, the sight of it driving a young boy mad; traumatic memories of war are represented by indistinct flurries of the violent clash of robotic limbs, or a decontextualized and repeated offer of money for bodies; a sentient teddy bear sits immobile, a puppet master at the mercy of whoever moves it around; a tiny figure is captured leaping from rooftop to rooftop in the final images recorded by a dying robot, its blurry body silhouetted against the sky.

You add all this to Urasawa’s usual page-turning panache, and suddenly what had felt like mere proficiency gains the power to haunt and to move. There are the usual resonances with and/or swipes from other genre-art touchstones: Brau 1589 is Hannibal Lecter with microprocessors, there’s an Iraq War riff as is custom with science fiction that wants to be taken seriously this decade, and the plot–super detective believes that other super beings of his acquaintance are being hunted by a serial killer so he travels around to warn them with varying degrees of success–is straight-up Watchmen Chapter One. Plus, the whole thing is an adaptation of a story about Japan’s Mickey Mouse/Superman cultural juggernaut. (“Flying boy robot in shorts” is the extent of my knowledge of Astro Boy, so what Urasawa is taking from Tezuka narratively or visually is beyond me.) But instead of coming across like button-pushing, all of this, and all the chases and clue-hunting and races against time and unsuspected reversals that are Urasawa’s thriller trademarks, now feels like ammo in the arsenal of someone taking aim at some big old-fashioned sci-fi questions about war, technology, human rights, friendship, childhood, and that old chestnut, what it means to be human. The thing that fills me with delight here is that when you look at that robot maid just standing and staring, unable to express her emotion, you get the sense that for once, this master penciller and plotter doesn’t have all the answers.

Comics Time: You’ll Never Know Book One: A Good and Decent Man

December 30, 2009

You’ll Never Know Book One: A Good and Decent Man

C. Tyler, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2009

104 pages, hardcover

$29.95

You’ll Never Know is a memoir about creating a memoir. In it, the affable but scatterbrained Carol Tyler, buffeted by her separation from her cheating, indecisive husband and by her own memories, finds solace in attempting to construct for her father a scrapbook chronicling his military service during World War II. As becomes clear during a climactic dream sequence in which Hitler proclaims that the trauma inflicted on her father during the War warms his heart from beyond the grave, doing this is much more to Tyler than an attempt to set the historical record straight or satisfy her own curiosity (though it is both of those things as well). It’s the product of a realization that something vital was taken from her father, whom she sees as hard-working, lovably ornery, and an incorrigible cut-up, yet also distant and damaged in a way that suggests a missing puzzle piece she might be able to reconstruct.

Therein lies the problem. So personal is the project to Tyler that in some basic ways it fails to translate to the reader. Her dad, Chuck, is a gruff dude to be sure, but funny and lively. He’s apparently a brilliant handyman, a helluva dancer, he swept the hottest girl in the base’s secretarial pool off her feat, he tears it up at the Pop Hop to which he escorts Carol as a teen, he’s undyingly romantic toward her mother, and most importantly he eventually unloads his previously unspoken military memories for her not once but several times–and yet Tyler insists upon the notion that the horror of his experiences in Italy broke him. It’s just not present in the text. In recounting the plot just now I realized how very similar it is to Art Spiegelman’s experience with his own father in Maus, which is a solid point of comparison–compared to the nightmarish psychological scarring the Holocaust inflicted upon Spiegelman’s parents, and how painfully Spiegelman evokes it, what Tyler’s up to in her depiction of her father remains obtuse.

Tyler’s confidence in the face of this lacuna is reflected in her buoyant but ramshackle art. Her comics’ landscape layout and dashed-off line and lettering (complete with blue-pencil guidelines) evoke a mid-tier slice-of-life webcomic; they’re pleasant and likeable, but they make this very serious and personal project feel slightly airy and inconsequential. They’re not helped in this regard by their presentation as a supplement to the actual scrapbook she’s putting together for her father, nor by her presentation of herself in an always slightly humorous fashion even when literally prostrated by her husband’s infidelity and departure. Transitions and juxtapositions, too, feel under-considered, from the cuts to and from her own life story to this volume’s abrupt cut-off point. I’m not saying her familial war story needs to be the unrelenting legacy of horror that was Maus–their experience was and is different and so should be Tyler’s book about it. But the effect of her writing and drawing serves to cut the tale’s gravitas off at the knees. I know it’s a story she needed to tell; I’m not convinced it’s a story that needed to be told, or perhaps more to the point, that I needed to hear.

Comics Time: The Photographer

December 28, 2009

The Photographer

Didier Lefevre, story/photographs

Emmanuel Guibert, writer/artist

Frederic Lemercier, colors/layouts

First Second, 2009

288 pages

$29.95

The high point of The Photographer is literally the geographical high point of The Photographer. After chronicling a Doctors Without Borders mission into the war-torn country–then occupied by the Soviet Union–lensman Didier Lefevre makes the ill-advised decision to leave his more experienced Western colleagues and return through the mountains to Pakistan alone. Abandoned by guides who barely knew the way themselves, Lefevre finds himself stranded at the summit of a mountain pass. In the gloom he desperately tries to make it through by nightfall, and is reduced to beating his exhausted, dying horse until he realizes neither of them can go any further. He bivouacs beneath his horse’s body, melting snow in his mouth in an attempt to stay hydrated, cursing his recklessness and the fecklessness of his escorts. Realizing that he will most likely never make it down the other side of the mountain, he writes a note to his girlfriend and then takes the most beautiful, dramatic, and chilling photographs of his journey, capturing his emaciated horse and the nightmarish wasteland that surrounds them, believing in his heart that they are the last things he will see. In the several pages that chronicle this most dire stretch of Lefevre’s memoir, artist Emmanuel Guibert manages to capture the photographer’s initial panic at being left alone in an unfamiliar place, contrasting his nervous movements and increasingly desperate drive to move on against the cold and motionless stones of the land and small dwelling where he was abandoned. And as Lefevre and his horse reach what he believes to be their final resting place, they are depicted solely in silhouette, black against the icy twilight blues provided by colorist Frederic Lemercier. The effect is a perfect evocation of Lefevre’s Sisyphean plight–frantic effort colliding with unyielding futility and ultimately despair. Gorgeous, frightening, powerful comics.

Alas, it’s one of the only sequences in the whole of The Photographer‘s 288 pages to which any of those four words apply. The story of Lefevre’s trip into and out of Afghanistan is plodding journey through a featureless wash of minutiae about his companions, their hosts, their jobs, and the land. Obviously, the choice to leech the proceedings of nearly any drama–save for Lefevre’s near-death at the mountaintop and a trio of gut-punch accounts of war-wounded children, nothing cuts through the haze of tedious detail–was a conscious one, meant to evoke the reality of life in a desperately poor and brutalized country, and how no grand Orientalist gestures are possible, only the quotidian work of traveling there, setting up shop, and treating those who can be treated. However, a flawless evocation of boredom is still boring.

Meanwhile, memoirists of conflict like Joe Sacco and Art Spiegelman have shown that dull horror can make for compelling comics. But Guibert’s work here is tough to classify as comics at all. Yes, there are panels, word balloons, caption boxes, but his visual contribution is essentially an unending series of stiff minimalist portraits that look like they were produced with a photoshop filter, or one of those dreadful animation projects that take live action footage and boil them down to a “cartooned” style. They demonstrate the story rather than tell it. Even on top of Guibert and layout artist Frederic’s lack of attention to image-to-image flow or to the composition of a page, big blocks of narrative text and the interspersal of Lefevre’s actual photographs all but prevent the effects of accumulative or juxtaposed meaning that are so crucial to the book’s nominal medium of comics. Backgrounds are frequently dropped altogether, replaced with a baffling, uncommunicative palette of pea green and acidic yellow; one rare sequence where backgrounds were present stands out for its wrongheadedness, with rocky terrain all but obliterating the conversation in which Lefevre argues the head of his expedition into letting him return by himself. That Guibert had it in him to produce that knockout climax makes the lack of energy and life in the rest of the book all the more depressing. Nobly intentioned though it may be, bad comics is bad comics.

Comics Time: Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys Vols. 4 & 5

December 25, 2009

Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys Vols. 4 & 5

Naoki Urasawa, writer/artist

Viz, 2009

200 pages, Vol. 4

216 pages, Vol. 5

$12.99 each

There are two major developments in these installments of Urasawa’s cult-conspiracy thriller. The first is the introduction as a secondary protagonist of Wolverine. The gruff longhaired badass who plays by his own rules but has a heart of gold and so on–named Shogun, in case you didn’t pick up on his awesomeness–was technically introduced in Vol. 3, but here we find out who he really is, get an origin story involving a wise old sensei, and connect him to the main thread of action. The second major development, which is interesting because it upends the first, is a big honking shift of the whole territory of the story that came waaaaaay quicker than expected. I won’t spoil it beyond the spoilage that is announcing its existence, but it’s what longtime watchers of Lost might call a “game-changer.” And if you opt to look at Shogun as the Sawyer figure instead of the Wolverine figure, that may be even more helpful in terms of establishing just how expertly Urasawa plays with genre tropes, insofar as these same tropes would later be key to the greatest work of American pop/pulp fiction this decade. 20th Century Boys has a lot in common with Lost, a neutral observation that doubles as an endorsement.

PS for readers of the series: The first lyrics in T. Rex’s “20th Century Boys” are “Friends say it’s fine, friends say it’s good.” Ha!

Comics Time: Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys Vols. 1-3

December 23, 2009

Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys Vols. 1-3

Naoki Urasawa, writer/artist

Viz, 2009

216 pages, Vols. 1&2

200 pages, Vol. 3

$12.99 each

I don’t like to read manga series until I have the whole thing. It’s not like superhero serials that are ongoing in perpetuity, or TV shows where the same thing is theoretically the case–these stories are serialized but they’re of a finite length, and I find that if I try to read a little here, a little there, I end up forgetting half of what’s going on by the time I catch up with later volumes. This isn’t really the fault of the material, mind you, it’s just because I’m not terribly bright.

Anyway, sometimes needs must, and so I found myself reading the three volumes of 20th Century Boys I have in my possession at the moment. (Without having Vols. 4-6, or god help me, without having finished Monster, since I’m missing about six volumes in the middle of the run and totally can’t remember what happened in the three or four volumes I already read. Like I said, not the sharpest knife in the drawer.) And this probably comes as a surprise to no one, but they’re a lot of fun. The story’s like a cross between Stephen King’s It and the Aum Shinrikyo Tokyo subway attack, with thirtysomething go-nowhere convenience-store franchisee Kenji discovering that the heroes-and-villains game he helped concoct as a kid is being used as a how-to manual for murdering people by a shadowy cult, most likely led by one of his childhood friends. The drill so far is one of watching bodies pile up and the revelations slowly accumulate, often in sublimely unexpected ways. There’s at least one supporting character who gets offed way before I’d have seen it coming, a lot of the secrets are way more out in the open than I’d have expected them to be at this stage in the game (a lot of “so, now you know that I know what you know”), there’s a wooly subplot involving a psychic bum, there’s a very cool t-shirt-ready symbol for the death cult…a thrill a minute, baby, and dammit, I wish I had the other three volumes.

That said, I think what prevents the Urasawa I’ve read from springboarding off its obvious proficiency with genre into the realm of genuinely great art is that his actual art, his drawings, are strictly functional. Actually, that’s not quite the word for it. “Strictly functional” implies “merely adequate,” and it’s more than that. The visual storytelling is crystal-clear, which is a huge help for a mystery translated from a foreign language with its own cultural cues. The character designs are easy to keep track of even as childhood friends are reintroduced at a dizzying pace. The line is as slick as manga gets, retaining energy during quieter scenes like a coiled spring that boings back up during confrontations and action sequences. But it only has style in the sense that, say, your basic Hollywood thriller has: The goal of the art is to stay out of the way of the story. I’m reminded of Pia Guerra’s work on Y: The Last Man–Urasawa would never draw anything that stiff, of course, but that kind of nondescript conveyor-of-information-type art is the sort of thing that works really well for a comic with this kind of broad civilian appeal. Are you here for an art class, or are you here to find out if Kenji can save the world?

Comics Time: You Are There

December 21, 2009

You Are There

Jean-Claude Forest, writer

Jacques Tardi, artist

Fantagraphics, 2009

196 pages, hardcover

$26.99

Wow, what a turnaround I made on this book in the space of a few pages. One of the perils of being so hung up about spoilers that you go into a book without even knowing what it’s about is that oftentimes it turns out you’ve got an idea in your head of what it’s about anyway, and that idea can be wrong. My only experience with Tardi was his adaptation of Jean-Patrick Manchette’s daylight-noir West Coast Blues, so when I saw a guy in a bowler hat standing there in a graveyard on the cover I figured “okay, a period-piece crime novel, like The Black Diamond Detective Agency or something.” Instead, right from the first page, you just get smacked with this torrent of verbiage from this daffy annoying tall skinny guy as he runs around atop the walls of some crazy little village opening gates for people. What the fuck is this?

It’s an absurdist satire, is what it is, and a pretty terrific one. And good God is it French. Once I realized what was up, my dim memories of Jarry and Ionesco and Beckett flickered one by one back to life. Delusions of grandeur, farcical authority figures, goofily symbolic names, talk talk talk that says nothing, all atop a fundamentally ridiculous premise.

Arthur There, the heir of a long-defunct line of aristocrats, has lost his ancestral estate but gained the legal right to erect walls between the properties of all the people who now live on it and control their comings and goings. Only by “control” I mean “run when they ring a bell for him to open the gate.” A Strangelovian element is injected when the president of France, on the verge of losing his bid for reelection, settles upon the unique legal status of There’s labyrinthine fiefdom as the perfect pretext for setting up a rival government-in-exile. He’d heard of the place thanks to Julie Maillard, the squint-eyed and slatternly daughter of the neurotic There’s chief rival–she once had a watersport-heavy affair with the President, though now her sights are set, for reasons obscure even to her, on There. And some other dudes too. It’s easy to picture it as one of those long-form fourth-season Monty Python episodes, with Eric Idle as There, Michael Palin as the President, and Carol Cleveland as Julie, if that helps.

So like I said, once I figured out what was up–once I realized that the dialogue was overwhelming and annoying on purpose, once I realized that the characters were deliberately ridiculous and their motivations purposefully flimsy and absurd–I was all the way on board. Kudos for that must go to Jean-Claude Forest’s full-bore commitment to writing like that. After a while it feels like the most natural thing in the world to watch There talk to himself on the verge of hysteria for paragraph after paragraph. But the real magic is in watching what Tardi does with Forest’s set-up. The fool’s kingdom of Mornemont is an unforgettable comic-book locale, and the riot of walls and fences and gates that crisscross it provide a perfect visual hook on which to hang the similarly profligate dialogue and nonsensical story. Tardi’s lanky design for There; his recurring motif of vertical stripes everywhere from the gates There opens to the wallpaper of his comically tiny house; his use of tall rectangular panels and layouts that emphasize the page’s verticality; truly masterful rainstorms and snowstorms–it’s seriously a master class on creating a sense not just of place but of a claustrophobic, chaotic, unsustainable state of mind. It isn’t hard to see this on your bookshelf next to Brian Chippendale, Mat Brinkman, or Hans Rickheit: environment and emotion are one and the same here as there. What’s more, the main effect is so clear that the contrasts are all the stronger: Mornemont’s white walls with the President’s black curtains; There’s googly eyes, stovepipe limbs, and funereal suit with Julie’s bovine expressionlessness, swooping curves, and frequently nude white body; the sealed-off snowglobe isolation of Mornemont throughout the book with the sudden border-smashing invasion by the outside world at the book’s climax. It’s a parade of comics effects astutely selected and deftly executed. Killer stuff, and more fun than you remember it from French class.

Comics Time: Plague Hero

December 18, 2009Plague Hero

Tunde Adebimpe, writer/artist

Suciotone, December 2009

28 pages

$4

I can’t find anyplace to buy it–let me know in the comments if you know of one

I’m not going to lie: I checked out the comic Tunde Adebimpe was selling at a table at BKCGF because of his day job. But come for the “Staring at the Sun,” stay for the, bright, fun, and effective painted fight comic. Printed on thick, glossy paper, Adebimpe’s paints really leap off the page as they illustrate his simple set-up, subtitled “A Few Notes on Being and Not Being Myself”: A pink horse guy and a green bird guy (his name’s Myself) square off from the left- and right-hand side of each spread in a boxing match narrated by a strip of playfully metaphorical first-person text running across the bottom. The anthropomorphic fighters are built like characters from an all-ages boxing video game, and indeed the simple two dimensional plane of the action reinforces that feel: Since all they can do is move forward, move back, and punch each other, it’s easy to feel like you’ve got a ringside seat to an all-action button-masher/slobberknocker. When the combatants land a blow, their wounded opponents explode with color at the point of impact; a similarly visually explosive cut to a pair of audience members (“prospective employers, future ex-wives”) manages to convey the roar of the crowd with similar effectiveness. Adebimpe’s writing bounces along with the hardboiled patter of an old-school sports columnist: “That’s when I decided to step in…and Reagan ’84 the poor jerk”; “It was our pan, and we were flashing.” In the end one of the fighters is declared the “WINNAH!” by knockout, which depending on how much you’re willing to play along with the Myself/Not Myself metaphor could Mean Something. But really it’s an exercise in convey action and movement through color and telling a story with a memorable voice–and a successful exercise at that. I hope to see more.

Comics Time: Feeble Minded Funnies/My Best Pet

December 16, 2009

Feeble Minded Funnies/My Best Pet

Lane Milburn/Noel Friebert, writers/artists

Closed Caption Comics, December 2009

28 pages

$7

Hey, they can’t all be winners. The overall Closed Caption Comics aesthetic, to the extent that one can be pinpointed, has long appealed to me: handmade, rough-hewn, silkscreened, markmaking shit, the ballyhooed stylistic dead-end of Fort Thunder in action, you know the drill. In particular I’ve become a big fan of Lane Milburn’s mix of muscularly drawn monsters and uncomfortable humor, gags that yuk it up until it’s too late and you realize how black things have gotten. That takes a real precise mind and hand to pull off. That’s not what you get in Feeble Minded Funnies, Milburn’s half of this flipbook minicomic, however. Instead he apes the broad humor and colloquial rhythms of the undergrounds: parodic violence, torrents of obscenities, a hapless protagonist called Pukeball making his way through a disapproving world while narration hammers his satirical plight home, all that sort of thing. It actually got to the point (right around the swipe at an outdated grim’n’gritty superhero stereotype) where I wondered if this isn’t actually a parody of underground comix. You’d have to be a lot meaner to make that sort of thing work, though. Actually, has anyone ever done a really nasty parody of the undergrounds? I could use one. Anyway. Milburn draws the bejesus out of it all–someday I want to sit and just watch how he puts the bodies of one of his goons together on the page–but the stories and jokes his awesome drawings inhabit here fall flat.

On the flipside you have Noel Freibert’s My Best Pet, which is the story of a sociopathic child who tortures his pets to death told in a sort of camp faux-EC mode. Longtime readers of this blog can no doubt imagine my reaction. I really hate being so predictable about animal-cruelty gags–apparently this even came up in the humor-comics panel at SPX when I wasn’t even there–but for real: another cat in the fucking microwave? What is it that people get out of drawing cats being blown up in microwaves? Are there people who enjoy…okay, that’s a loaded term. Are there people who get something out of comics in which cats are blown up in microwaves? These are not rhetorical questions at all, by the way. I’m a person with a very high tolerance, a need even, for nihilistic horror, but this I don’t get. Like I’m fond of saying when I come across this sort of material, I’m okay with it when I feel as though the artist is attempting to elucidate something about cruelty. But the whole point of this comic, and it’s actually quite entertaining in this regard, is that it’s just going through the motions. Friebert depicts the asshole kid’s parents’ discussions about his plight without even bothering to put them on panel–it’s just panel after panel of exposition, like they can barely be arsed to show up and play their role in the strip. That’s very funny. And yet we get the cat’s oblivious mewlings as it’s placed in the microwave and its subsequent screams of pain in painstaking detail. I mean, fuck that, right? I’m not the only one?

Comics Time: City-Hunter Magazine #1

December 14, 2009

City-Hunter Magazine #1

C.F., writer/artist

Fantasy Empire Magazine Co., December 2009

20 pages

$3, I believe

I have no way of contextualizing this thing. It’s not Powr Mastrs, it’s not even a smaller and stranger but still-quite-obviously-a-minicomic minicomic like Core of Caligula. It’s billed as a “zine,” and there’s a comics sequence, yeah, but it’s mostly illustrations and sketches and doodles and a couple of goofy prose pages and a blown-up xerox of a piece of an issue of USA Today. As such? I still really enjoyed it. C.F. gains more from inscrutability than just about any other working cartoonist; at its best his stuff already has an air of mystery to it, so when stripped even from the relatively loose standards of his “proper” comics, the way he writes out phrases like “MANSION SOFT DRINK” scribbles them out, writes them over again, and follows them up with a stand-alone image of a person walking past a fancy-looking window toward a soda machine, say, takes on a whole new weight. Who the hell is “LUCIO” and why is his name taking up half a page? What does any of it have to do with those rather sexy bondage pin-ups–one of them in full color? Beats me, and that’s quite fine.

The things I could make sense of tickled me, at any rate. The titular strip, set up with a prose introduction by “editor” “Mike Rennet” (does he exist? does it matter?) about the need he felt to discover the big city when he moved to it, follows around a little dude in a memorably C.F.-ian jumpsuit as he walks around the city and just stand around in various places. It’s kind of Pythonesque in its vibe, though I’m finding it difficult to convey. All I know is that I laughed. Same with the second text piece, an editorial from Rennet about how if you live in the city you have to live it up:

Now if you’re reading this thinking I’m standing still in my own poison, mortified by my past and terrified of my future, you’ve got another thing coming. And that thing is my scared, angry fist, smashing through your apartment wall. Your messy, overpriced, uncool, apartment… wall. You’re going to shrivel up; because you don’t know anything about how to work this city, man.

It ends with an exhortation to check out the author’s Facebook page. I got my $3 worth out of this and that’s all the context I need.

Comics Time: A Drifting Life

December 11, 2009

A Drifting Life

Yoshihiro Tatsumi, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, 2009

856 pages

$29.95

I have a friend from college who every time I talk to him we’ll just end up talking about comics and music and movies, and then I’ll hang up and my wife will be like “Did you tell him about our new house?” or “I saw on his girlfriend’s LiveJournal they got a new dog?” and I’ll just have to shrug my shoulders, because there was no way we could fit topics like that into our discussion of Dragon Head or John Romita Jr. or whatever. This massive autobiography is like that: It’s about the joys of pure unabashed obsessive nerdery, the almost physical pleasure of talking and thinking and writing about and working on nothing but the art you enjoy. That makes it an easy book to like. So does Tatsumi’s appealingly simple and direct art, which like a McCloud thesis in action presents Tatsumi and a galaxy of manga-pioneering stars as lovable little caricatures you never get sick of watching and rooting for. And so does the history lesson about the Japanese comics industry that it inevitably teaches. Comics as a mass medium, comics as a legitimate art form, book-format comics, comics in a variety of genres for a variety of age groups and interests–nearly everything the American comics industry is only now achieving, and in some cases may actually never achieve, Japanese comics had already done decades ago. It’s like if we’d fought World War II against Hicksville.

The thing is, much of what makes it such an easy book to like also makes it a hard book to love. Tatsumi’s relentless focus on manga, its omnipresence as the focalizing device for the story, left me scratching my head about whether other aspects of his life really did intrude upon his writing and drawing as perfunctorily as he shows them doing here. I mean, just as an example, was this dude really that uninterested in getting laid throughout his teens and early 20s? There are of course a couple of nods in that direction but they just make the relative absence all the more conspicuous. Early in the book his family plays a larger role, which makes sense because he lives with them. But his brother (and frequent coworker and collaborator)’s illness, his parents’ loveless marriage, his father’s ne’er-do-welling–did they just go away?

What’s more, the book is more about the business of manga, and making a living in it, than it is about the art itself. For every page-long disquisition about the nature of the mature “gekiga” style of comics storytelling Tatsumi helped pioneer, there are dozens about catching a train to drop a manuscript off so that he can collect a paycheck from a publisher before they declare bankruptcy or whatever. That sort of thing is a lot of fun, don’t get me wrong–when I wrote my oral history of Marvel Comics I could have sat in Joe Simon’s apartment and listened to him ramble about him and Jack Kirby fighting with Martin Goodman for hours–but it’s not going to have the impact that really digging into what made young Tatsumi tick as an artist could have had.

Indeed, the book just picks up with li’l Tatsumi already a hardcore manga fan. We never learn what hooked him to begin with, and that’s an absence that’s reflected, in its way, right up until the end: The story cuts off abruptly as Tatsumi, literally swept into a violent protest against the government by a surging crowd, connects the anger of the protesters to the ingredient he’d felt had gone missing from his own work. I assume this was the last moment Tatsumi doubted his career path? Or perhaps it was the last moment he felt blocked as a writer or artist? It’s not clear why after 800-odd pages, this is where it all ends. Like the action kicking off in medias res in terms of Tatsumi’s love of manga, it’s an odd lacuna.

One of the insights we really do get into Tatsumi’s gekiga is that it’s intended as a type of minimalism, a sort of off-kilter spareness traceable to cinema and hardboiled American detective fiction. (Its lack of text made it an easy target for bluenoses, who said that any comics page that was two-thirds wordless or more was automatically immoral.) And the book’s definitely economical in the sense that it’s a no-nonsense flow of images and text smoothly propelling us from one thing to the next as Tatsumi’s career progresses. But the constant narration rarely gives story or reader a moment’s pause. Couple it with the “on this day in history”-type panels featuring highlights from Japan’s cultural and political evolution during this time, and it’s easy to feel like you’re skimming a life rather than drifting through one. (Which reminds me, if this is what passes for A Drifting Life for Tatsumi, whose sole, laser-like focus throughout is drawing manga for a living and who busts his ass day after day and year after year to make it happen, I’d hate to think what he’d make of me!)

I think A Drifting Life is a fine book. (I definitely like it a lot more than the kind of ham-handed violent O. Henry short stories I’ve read by him.) Reading it is a lot like plowing through a long run of a serialized comic in one go: It’s a delicious, I wanna say tactile experience, and the subject matter guarantees it’s time well spent if you love comics enough to read a blog like this one. You’ll recognize a lot of yourself in it. But I suspect that that recognition comes at the expense of revelation.

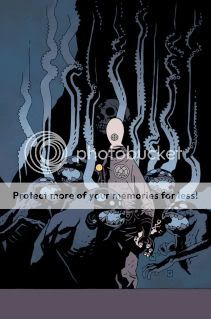

Comics Time: B.P.R.D.: War on Frogs #4

December 9, 2009

B.P.R.D.: War on Frogs #4

John Arcudi, writer

Peter Snejbjerg, artist

Dark Horse, December 2009

32 pages

$2.99

I never thought I’d see the day where I’d be happy that Dave Stewart didn’t color a Hellboyverse book. But on this New Comics Wednesday, the best colorist in the front of Previews finds himself stranded in Brown Town in the pages of Fabio Moon and Gabriel Ba’s Vertigo series debut Daytripper. And he’s left colorist Bjarne Hansen to absolutely kill it in conjunction with artist Peter Snejbjerg in this concluding issue of the gap-filling series of glorified BPRD one-shots. Generally he hews close to Stewart’s long-established palette of full blues, reds, and greens, designed to contrast against the usual washes of black (and if I’m not mistaken derived from Matt Hollingsworth’s work in the initial Hellboy miniseries). But in the issue’s spectacular climax, he adds flourescents that wouldn’t look out of place in Tron; it’s something we’ve never seen before in Mignola World, and the effect is a stunning way to suggest the Otherness of what we’re looking at. Further, Snejbjerg’s art, already a winning riff on Guy Davis’s model that smoothes out some of the rough edges in favor of a wispy vulnerability, is put through a focus-blurring filter, as if poor Johann Kraus’s view of the next world literally can’t be visually comprehended. It’s a lovely, clever, and chilling way to drive home the story by John Arcudi, which is yet another tale of one of our ostensible heroes realizing he’s in way, way over his head but continuing to struggle simply because the alternative is unbearable to contemplate. The quality control for this ever-expanding franchise during the course of this decade is one of contemporary genre comics’ minor miracles, and this issue is a happy example, and by happy I of course mean melancholy and pessimistic as Hell.