Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

Comics Time: Closed Caption Comics #8

July 2, 2010Closed Caption Comics #8

Erin Womack, Pete Razon, Lane Milburn, Zach Hazard, Mollie Goldstrom, Chris Day, Molly O’Connell, Ryan Cecil Smith, Andrew Neyer, Erin Womack, Eric Stiner, Conor Stechschulte, Noel Freibert, writers/artists

Closed Caption Comics, February 2009

80 pages

$8

Maybe you can buy it at the Closed Caption Comics blog someplace too, beats me man

This is the kind of comic that makes me excited to be into comics. The eighth installment of the Baltimore-based CCC’s flagship anthology resembles nothing so much as a great early Wu-Tang Clan posse cut, with all eleven (!) members contributing powerfully cartooned, hungry-feeling work that’s alternately funny, frightening, and fearless. Me being me, I was particularly struck by the issue’s sometimes dueling, sometimes intertwining apparent themes of horror and sex. In that regard the standout piece was by Conor Stechschulte, who turns in an absolutely brutal story of a circle-jerk gone horribly awry, augmented by his pitch-perfect evocation of a shadow-soaked suburbia. But on the flipside I laughed hard at the dirty jokes from Zach Hazard and Chris Day, the bathroom humor from Hazard and Andrew Neyer, and the monster-comic goofs of Lane Milburn (impeccably, muscularly drawn as always). Noel Freibert serves up maybe his most left-field EC Comics-inspired story to date, with some genuinely unpleasant and painful imagery; its rawness, ugliness, and reliance on bare, ropey line is like some sort of cross-artist call-and-response to the esoteric, almost mystical loveliness of the images concocted by Erin Womack, or the strange…I wanna say floral body-horror of Molly O’Connell. Eric Stiner channels Tom Gauld, Ryan Cecil Smith channels Brian Ralph channeling Tatsuo Yoshida, Mollie Goldstrom comes across like a maximalist John Hankiewicz, and Pete Razon submits some funny scribbles to round out the package. 80 pages, eight bucks, renewed faith.

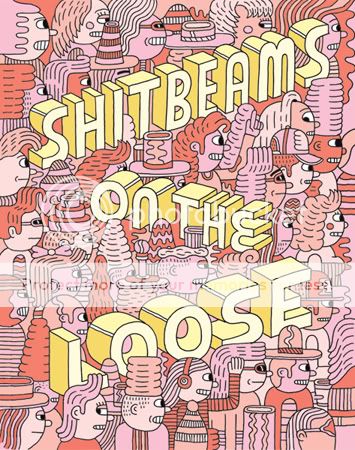

Comics Time: Shitbeams on the Loose #2

June 30, 2010Shitbeams on the Loose #2

Andy Rementer, Ron Rege Jr., Jason Overby, Dave Nuss, Andrew Smith, Hector Serna Jr., Brent Harada, Robyn Jordan, John Hankiewicz, Grant Reynolds, Ryo Kuramoto & Amane Yamamoto, Rusty Jordan, Luke Ramsey, writers/artists

Rusty Jordan, Dave Nuss, editors

Revival House, October 2009

60 pages

$9

I picked this up on the strength of that gorgeous Andy Rementer cover, which at the time I thought was by Ron Rege Jr. That’s actually a pretty appropriate way to have discovered this artcomix anthology, in which there are several pieces strong enough to make you think “hey, this was worth taking a flyer for nine bucks” and several others that you could mistake for the work of other cartoonists and then some stuff that you just move on by. I’m always up for new John Hankiewicz, and thus my favorite piece is his wordless sequence of four full-page images, which paint a quietly creepy portrait of some kind of dark domestic fairy-tale. It’s followed by some bravura inkwork by Grant Reynolds in service of a gruesome underwater flying-saucer sci-fi tale, peppered with non sequitur quotes in big block letters that feel like faintly received transmissions from the strip’s helmeted voyager. And I was tickled by both Dave Nuss’s look at the underpaid centurion who stabbed Christ in the side and the stylized drawing of “tubgirl” (google at your own risk) that Andrew Smith provided for the back cover. Beyond that? There’s some not-his-best stuff from Rege (really, this time), a “comic about comics” from Jason Overby whose visuals fail to live up to insight of the text, and some stuff that’ll remind you of Ben Jones, Matt Furie, Michael DeForge, Bald Eagles, you know, the whole wildandwoolier end of that scene. It’s inessential, but if you like this sort of thing, it’s the sort of thing you’ll like.

Comics Time: not simple

June 28, 2010not simple

Natsume Ono, writer/artist

Viz Signature/Ikki, January 2010

320 pages

$14.99

I’m gonna go so far as to say don’t waste your time with this one. Sure, the cover makes it look like an imported slice-of-lifer of the sort that’s at least surface-level appealing to American altcomix readers like me. But inside is a story so rife with tragedy, maudlin melodrama, and ludicrous implausibility it feels less like, say, Solanin and more like something you’d waste a couple Saturday afternoon hours watching on Lifetime. Its confusing intro at first makes the book seem like it’s going to be about a totally different person and scenario and then gets barely a dozen pages before lobbing the first in an onslaught of absurd coincidences, all of which come in lieu of a plot that emerges organically from character. When we finally do get around to telling the story of our protagonist Ian–a young man recovering from abuse and hoping to reunite with the older sister he suspects was secretly his birth mother–it quickly becomes clear that Ono’s art isn’t up to the task she sets up for herself, in which the characters’ appearances and who looks like whom are a major plot point. She’s not really making up for it with style or layout either: Her angular line and big-eyed emo-haired impossibly slim characters are pleasant enough for a time, but they wouldn’t look out of place in an undistinguished minicomic being sold at a MoCCA table, and her panels feel cramped and at times illogically placed. There’s a comparatively strong, thoughtful, intriguing subplot-cum-A-plot involving a young writer who befriends Ian with the intention of writing a novel about his tragic life but quietly falls in love with him. It nearly rights the ship, but only nearly, especially once it’s capsized once again by the most over-the-top plot twist of the lot. I’ll say this for the book: it reads like a breeze–even if that’s in part because the art is slight and you’re racing through the narrative since it doesn’t reward dwelling.

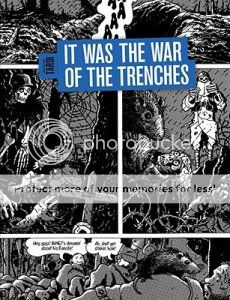

Comics Time: It Was the War of the Trenches

June 25, 2010It Was the War of the Trenches

Jacques Tardi, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, March 2010

120 pages, hardcover

$24.99

Just a few observations on the art here:

1) With the exception of the introductory story, this entire book features three tiered panels per page. In superhero comics this format is known as “widescreen”; it connotes power. It’s powerful here, too, but it’s a power to oppress and crush rather than soar or punch in action-movie style. They’re like miniature trenches.

2) In one memorable sequence early in the book, soldiers leap up from their trench and charge their opposite numbers. Their charge is depicted against a blank white background in lieu of any kind of detail for the sky or the horizon. You see men cut down by invisible bullets–no speed lines, no blurs, certainly no enemy firing.

3) One particularly strong page in the sequence uses panels of two soldiers leaning forward to sandwich a grisly shot of a soldier being blown backwards–hat flying off and blood streaming out behind him–by a bullet to the head.

4) Tardi’s art frequently piles detail on detail–meticulously researched trenches filled with the detritus of war, huge gatherings of massed soldiers in impeccably drawn uniforms and toting forests of guns and bayonets–but one thing he rarely if ever does is bury his protagonists in the visual cacophony. Flipping through the book, it’s impressive how he uses various tricks to pop them out from their surroundings. Most frequently, he’ll use the device of having people face directly out at the reader in weird little pseudo-portraits of them against their backgrounds. This is where the strength of his portraiture–his signature taciturn squinty-eyed stubbly everymen–comes in.

5) But he also uses a lot of forward motion, characters moving or leaning from the left-hand side of the panel to the right, serving as guideposts for your eyes and thus standing out to you.

6) It’s actually interesting to see the cases where people face right to left instead. I don’t think it’s always used for effect–it’s not like every single time is like that famous sequence from Safe Area Gorazde where Sacco drew people fleeing through a forest from right to left, “against the grain” of the reading experience if you will, to drive home the difficulty of their journey. But flipping through, I see some notable cases–a man seizing a suspected traitor, wounded Englishmen leaving the front, two soldiers from opposite sides of the conflict hiding out in a basement together, a soldier who gets lost in No Man’s Land sitting and trying to figure out which way to head…in most cases it suggests an inability to escape.

7) The whole book seems smeared with zipatone, dingy and dreary, like you’re being rained on. It makes the un-shaded parts–that attack sequence, a series photo-like images of the wounded and disfigured veterans toward the end–practically radiate from the page.

All of which is to say that this is Tardi’s thesis, as articulated in his foreword:

There are no “heroes,” there is no “protagonist” in this awful collective “adventure” that is war. nothing, but a gigantic, anonymous scream of agony.

…and but for my own personal history I’d be tempted to dismiss this as Captain Obvious territory. But the specific and unique awfulness of World War I is that trench warfare by its very nature highlights the pointlessness of the deaths of its participants: Untold thousands upon thousands of men standing up, moving forward a few feet, and being blown to pieces, gaining no ground, rinse, repeat for years on end. Add to this the French experience of many many soldiers being executed by their own side on entirely spurious or totally unfair accusations of dereliction of duty, a duty that was frequently impossible for them to execute. Tardi is brining very specific and very effective weapons to bear in his chillingly successful effort to convey this particular horror.

Comics Time: Peter’s Muscle

June 23, 2010Peter’s Muscle

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

self-published, May 2010

12 pages

no price listed

The second panel in this comic, a view of the buildings lining a city street–here, you can see it yourself–literally made me say “whooo” out loud on the train. Yeah, I’m quite frankly impressed as hell by what I’ve seen from Michael DeForge so far. This minicomic contains two nightmarish short stories, both of which pivot off of characters from popular comics (Spider-Man and freaking Foxtrot respectively) as is DeForge’s apparent wont, and they’re maybe the tightest things I’ve seen from him yet. The first involves Spider-Man recounting to his therapist a sex dream he had about Aunt May and Doctor Octopus; it’s not a “haha look the famous corporate icon is doing something dirty” joke, it’s a way to make this sort of uncomfortable Freudian stuff even more up-close-and-personal by using the familiar visual vocabulary of a hugely popular pop-culture staple to keep everything painfully simple to understand. The second shows a loinclothed character wandering through a wasteland whose geological features seem to consist solely of viscera, killing a phallic animal, and offering its disembowled corpse to the colossal, godlike, bifurcating head of a cute comic-strip kid. Again, this kind of “cute thing doing gross thing” material might read as overly broad in less skilled hands, but DeForge appears in complete control of his line, his figurework, his character designs, his backgrounds, his use of zipatone, his cartoony satirical representations of Spidey and Doc Ock and Aunt May, his pacing, his punchlines, his choice of nightmare imagery (sidewalk-as-thin-membrane is gonna be hard to shake when I walk to the comic shop today)…it’s very, very sharp, it does exactly what it wants to do.

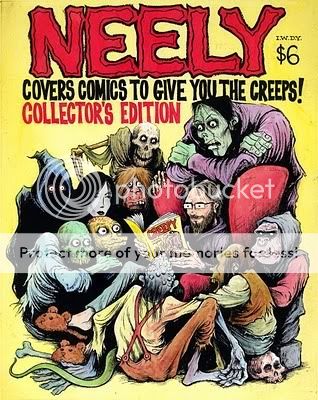

Comics Time: Neely Covers Comics to Give You the Creeps!

June 21, 2010Neely Covers Comics to Give You the Creeps!

Tom Neely, writer/artist

I Will Destroy You, May 2010

24 pages

$6

Tom Neely’s “cover versions” of various classic (or in some cases just old) horror comic covers have been a highlight of the Internet ever since he started putting them up on his site and on Robert Goodin’s never-miss-a-day Covered site. So naturally a collection of them is gonna be a treat if you’re into that sort of thing. But I think this minicomic is worth the price admission for more than just horror-hound eyecandy.

For one thing, it’s more like an eye-dessert cart, in large part due to the colors. People ought to be studying that lush midnight blue background in Adventures Into Terror, that sickly purple twilight in Beware the Clutching Hand and Unearthly Spectaculars, the candlelight effect giving way to a rich orange shadow in Creepy #79. That the comic’s paper holds them as well as it does is a testament to Neely’s skill as a self-publisher in addition to his instincts as a colorist.

For another, this collection is a sort of capsule version of the horror gospel according to Tom Neely. Not so much in the selections as in the interpretations, a picture emerges of what it is that Neely finds frightening; put simply, it’s the vulnerability of the body. His figures are both rail-thin and out-of-shape, a brand of body horror not far removed from black-and-white photos of the prisoners of Andersonville or Auschwitz. They grasp and point with arms that look like they could be snapped in half like twigs–honestly, Beware the Clutching Hand could serve as the title for Neely’s whole oeuvre. And there’s a horror of hair here as palpable as anything outside of The Ring. Weedy black locks cascade out from the heads of women like snakes and sprout from the heads and faces of men like anemones, suggesting an intense loathing of the way our bodies behave beyond our control. It’s like a zombie apocalypse perpetrated by sentient armpits and groins. All told, it’s much more than a series of kitschy nostalgic pin-ups. Creepy? You betcha.

Comics Time: Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka

June 18, 2010

Pluto: Urasawa x Tezuka

Naoki Urasawa, writer/artist

Takashi Nagasaki, writer

Based on Astro Boy: The Greatest Robot on Earth by Osamu Tezuka

Viz, 2009-2010

Eight volumes

200 pages or so each

$12.99 each

I was over the moon for the first three volumes of Pluto, suspense mangaka Naoki Urasawa’s Watchmen-style reimagining of a classic Astro Boy storyline–and for precisely the same reasons lots of other smart critics weren’t. I love stories about emotionally wounded men (or in this case, robots) crying over the death of puppies and children. I love stories about people paralyzed by grief and loss. I love stories about people who lay it all on the line, and lose it all, to save other people, and then how those other people handle being the reluctant beneficiaries of that sacrifice. In a word, I love melodrama. If it involves robots, so much the better. And in Pluto, I felt for the first time that Urasawa was connecting with something more than mere story.

Ultimately the series fails to fully live up to the magical magisterial melodramatic pomp of that first volume. As I found to be the case with Monster (although certainly not to that extent), Urasawa’s technique of drawing out characters’ climactic realizations and confrontations for page after page eventually dilutes their impact. In this particular case, the murder mystery at the story’s heart ends up being solved in a fashion that’s both disappointingly straightforward in terms of motive and unnecessarily, distractingly complicated in terms of execution. And since this is a super-robot story, the climax must come about through combat, ironically the one thing that Urasawa’s visual vocabulary does not enable him to portray in the most thrilling of all possible ways; particularly given the environment in which the final battle takes place, it’s difficult to get a handle on where you are, what’s going on, or what the consequences for each beat might be. Like the characters whose fate will be determined by the battle’s outcome, you just have to take it on faith that the involved parties know what they’re doing and things will come out in the end.

That said, the robots, and their surreally obtrusive appearances in Urasawa’s meticulous blend of realism and slick cartooniness, never ceased to be a joy to look at and never stopped lodging themselves in my brain. The repeated use of flashbacks to horrible events that haunt the main characters had that same effect on me. I came to care about these people/”people”–well, more like I came to be intrigued by them. I wanted to find out what happened to them to make them the way they are, and for things to work out for them, and I was frequently surprised when things went bad way before I thought they would. And in the end I appreciated the book’s blend of deep, unshakable, even scientific pessimism about human nature with an impassioned insistence that we can reject that programming if we try–in a fashion that’s a lot more convincing than the similar moral throughline in Monster, by the way. It may not stick the landing, but it’s a thing of beauty in flight.

Comics Time: Ex Machina Vols. 1-9

June 16, 2010Ex Machina Vols. 1-9

Brian K. Vaughan, writer

Tony Harris, artist

with John Paul Leon, Chris Sprouse, artists

DC/WildStorm, 2005-2010

various page counts

$12.99 each

There’s something lovably clunky about Ex Machina. Before we get to the lovably, let’s talk about the clunky, from the ripped-from-NPR political factoids that in some cases all but replace actual dialogue to the silent-movie mugging and gesticulating of Tony Harris’s photoref’d art. In my re-read of the series in three or four sittings prior to its imminent conclusion with issue #50, I was struck by just how clunky it is, particularly at first–much more so than I remember it.

Those first few issues get over largely on the strength of Brian K. Vaughan’s unfuckwithable high concept, the most button-pushing such idea in a career already full of them: Main character Mitchell Hundred is a New York City civil engineer whose contact with a mysterious artifact gives him the ability to communicate with machinery, inspiring him to launch a second career as a masked vigilante which culminates in his diversion of the airplane aimed at the second tower on 9/11 and leads to his election as mayor months later. So strong is that final page of the first issue, with one tower standing next to the light beam used to memorialize the second, that it’s easy to forget how Hundred’s politics are a “both sides make good points” centrist-pragmatist-contrarian hodgepodge that’s both unwieldy and unconvincing. Having the aforementioned both sides shout their points at Mitchell and one another via his various advisors, staffers, and constituents doesn’t help matters, especially because they’re usually concocted in such a way as to smack you over the head with “hey look how ideologically diverse this city is, you can’t pigeonhole anyone, we’re here to challenge your preconceptions, it’s not as simple as Left/Right black/white etc etc.” If you meet a priest, you can bet he’ll also be a boxer who takes the Lord’s name in vain; if a gay couple’s gonna get married, you’re damn straight they consist of one of the city’s, like, eight black firefighters and a Log Cabin Republican. Meanwhile they all point and shrug and flail about like they have some sort of neurological condition. It’s quite silly-sounding and silly-looking at times.

And yet! Just because a choice of how to write or draw something isn’t the choice I would have made doesn’t mean those choices can’t work on their own terms. For example, I always preferred Ex Machina to the other BKV book written in this vein, Y: The Last Man, because of Pia Guerra’s stiff art on the latter–even though I think that stiffness, that neither-fish-nor-fowl not quite naturalistic not quite cartoony look that was Vertigo’s house style for so long, is a big part of what makes that book such a hit with people new to comics: It’s simple and clear, yet not “childish.” Rereading Ex Machina this time around, I had a few flashes of suddenly thinking “Guerra Was Right”: Maybe her simplified, styleless figures are the perfect vehicles for Vaughan’s dialogue in his sociopolitically tinged series, where complex ideas are boiled down into streamlined approximations thereof in much the same way. Maybe Harris’s almost fumetti-like fealty to his models is what makes Vaughan’s Trivial Pursuit: Fiorello LaGuardia Edition dialogue feel so weird here and there.

But you know what Harris does have, in spades? Style, even glamour. Compared with the white glare of that other famous photorealist, Alex Ross, Harris’s art is awash in thick blacks that seem to make his figures both shine and swirl, and their eyes light up the room like Ellen DeGeneres’s when your’e watching American Idol in HD. (Seriously, that woman has unbelievable Lord of the Rings eyes.) Their world of constant grinning and shouting may be one uncanny valley removed from our own, but it’s still a world it seems like it’d be fun to hang out in, argue in, get embroiled in a political crisis or hostage situation in. It’s buoyant, it’s bright, and even the recurring grand-guignol violence feels like some sort of pop-art explosion as much as a series of brutal murders.

And in reading all nine of the currently collected volumes back to back, I discovered so much to enjoy about Vaughan’s writing, or more specifically his plotting. I’d never noticed before that each arc features a masked “villain” of some sort, even if it’s more likely to be someone who stole a fireman’s outfit from the set of Third Watch than a genuine “bad guy.” I also never picked up on the fact that while Hundred and his confidants self-consciously refer to Jack Pherson–a super-powered stalker who gained the ability to communicate with animals in an attempt to crack and duplicate Hundred’s power–as his “arch-enemy,” the book also features a real arch-enemy in the sense of a character plotting behind the scenes to take Hundred down for pretty much the series’ entire duration. In other words, like many heroes, Hundred has a “fighter” arch-enemy and a “thinker” arch-enemy. And by contrast with so many serialized genre entertainments of the past decade, the mythology elements are doled out so judiciously I’d forgotten they even existed. Seriously, you can go for twenty issues at a time before a given reference to the mystery of Hundred’s powers is repeated or followed up on; I can think of at least one very major one from the book’s second arc that still hasn’t been mentioned again. Once you get into it, even the speech becomes easy to enjoy. Vaughan clearly has a blast cussing, for one thing. Moreover, behind the didactic dialogue lurks the satirical concept that the only way to power through the avalanche of ossified bullshit that is politics and government is for a superhero to essentially bully people into it.

But it’s important to note that Vaughan in no way thinks this is a good idea. Indeed, the real secret to Ex Machina‘s success for me is that Vaughan announces, from the first page (set after Hundred’s term ends; everything that follows is a glorified flashback), that the story is a tragedy. Hundred’s personal heroism and political maverickiness will all end in unspecified disaster, perhaps for him, perhaps for the whole city–and as the issues go by, it seems possible that it’ll end in disaster for the whole world. All the characters who argue and chuckle and backslap their way through this whole NYC morality play have no idea what kind of story they’re actually in, but we do. Some rough beast is slouching toward Gracie Mansion, and the tension between the zesty surface gestures and the dark heart beneath is what will ultimately make these ten volumes worth returning to.

Comics Time: Studio Visit

June 14, 2010Studio Visit

James McShane, writer/artist

self-published, April 2010

48 pages

I don’t know how much it costs

Contact James McShane, I bet he can hook you up with a copy

Like his excellent minicomic Archaeology, James McShane’s Studio Visit explores the intersection of memory and environment. And like the cleverly conceived but ultimately more interesting in practice than in theory log-comic from Kramers Ergot and Ivan Brunetti’s Yale Anthology of Graphic Fiction, it explores the Heisenbergian interaction of lived experience and the recording thereof. It’s not as successful a comic as the former, nor as flat a comic as the latter. What it is is gestural, I think–McShane’s minimal lines, both of art and narration, get across a day in the life, from aspects of his daily routine to memories of past experiences evoked by objects he comes across in his house to his thoughts on process and his past works. That last bit’s maybe the most interesting–I was fascinated to hear that Archaeology was assembled in an almost Burroughsian cut-up fashion, and I also appreciated the quiet confidence in his explanation of how his very formal methods make him a better observer of what’s worth drawing. I think his…taste, maybe? gets away from here a bit–the memories he recounts of fun adventures in nature with friends are a bit on the twee side, the balletic image he chooses to represent “presenting the mundane with elan” is knowingly cheesy but cheesy nonetheless, and his vision of “growing” a story is depicted with too-literal gardening imagery. But the book isn’t intended to be anything more than what the title implies: a visit to the space, mental and physical, McShane inhabits when he works. This is where he was working on that particular day. It’s the recording of a step on a path, not of a destination reached.

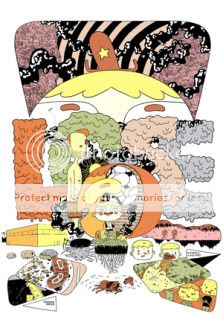

Comics Time: New Painting and Drawing

June 11, 2010New Painting and Drawing

Ben Jones, writer/artist

PictureBox, 2008

32 pages, hardcover

$20

See a preview at BenjaminQJones.com

You can’t understand New Painting and Drawing until you have it in your hands. It shimmers, as though the Platonic ideal of the color Orange just gave birth to a bouncing baby book. I actually think the Platonic ideal is a good concept to keep in mind when looking at Paper Rad honcho Ben Jones’s stuff. It’s like, “So be it–if I must draw a dog, then let it be the best of all possible dogs!” So you get a dog that is as wide-eyed and jolly as any dog you’ve ever petted, but he’s also bright orange and pink and yellow and aqua and another shade of orange, and he looks like he just stepped out of some sort of electronic animal shelter run by Shigeru Miyamoto, and he’s placed against a background of white-and-gold diagonal stripes, the better to pop him off the page and into your eyeballs. You get religious-iconography pastiche, but the icon is like Jesus and Mary and a Greek Orthodox saint all rolled into one, and he’s wearing Joseph’s Amazing Technicolor Dream Coat and a Ring Pop, and he’s got a mustache and is pointing almost like Buddy Christ, and he’s placed against a sky that looks like Apocalypse Tron. Jones’s obsessive use of patterns, stripes, brick fields and so on, each tier done in as bright a neon as you please, serves to foreground everything, backgrounding nothing. Every part of every drawing is designed to be as exciting as possible. It is such a thrill looking at this book.

Comics Time: Gags and Sloe Black

June 9, 2010Gags and Sloe Black

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

self-published

Gags – 18 pages, 2007; Sloe Black – 12 pages, 2008

Read them at DeForge’s website

These are sort of more what I anticipated when I got a package full of Michael DeForge comics in the mail–arty, xeroxy, at times consciously illegible transmissions from an alien design aesthetic. That’s almost all there is to Sloe Black, a small zine showcasing a series of vaguely humanoid shapes constructed with twisting, dripping, rope-like lines, and triangles and dots repeated with an almost schizophrenic intensity. These aren’t comics or narrative images, not by a longshot–they’re a visual braindump, they’re what you sort of imagined abstract painting was supposed to be about. It’s sort of like getting a sense of what DeForge’s “sound” is before you hear it applied to a song structure.

You get more of that sort of thing in Gags. Though the art is slightly less far out, it’s still drawing on that same basic melty, drippy, metal-illustration-influenced visual vocabulary, with a series of portraits of monstrous, faceless figures made of goo and teeth. But they’re juxtaposed with a series of well-chosen non sequiturs from everyday dude-life. “You don’t understand–playing drums is my life” reads the all-caps caption for a beast with a mouth growing out the side of its head and a knife with which he’s exposing his own ribcage; “Fuckin’ Carlos man–dude scares off so much pussy” says a beast whose body sits atop its head rather than the other way around. Besides having a flair for the zine-culture grotesque, DeForge has a great comedic ear for what happens in the company of bros.

Comics Time: Lose #1-2

June 7, 2010Lose #1-2

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

Koyama, 2009-2010

24 pages each

$5 each

You could be forgiven for thinking Michael DeForge’s solo anthology series would be, and I’m using this word in its value-neutral sense, a mess. In terms of the vibe DeForge’s work gives off in single illustrative images, or in his dense and frequently deliberately illegible all-font/logo-design installment in Frank Santoro’s Cold Heat Special series, or in his xeroxed minicomics, or even on the covers of these very comics, the operative word is “noise.” And it’s a sort of noise that owes more to both the toner-smeared world of zine culture and the fine-arty fine-lined zaniness of Canadian art-toonists like Marc Bell or Keith Jones, than to the chunky, punky, living, breathing environments of the Fort Thunderites. Throw in those noxious, acidic greens on the slick covers, and it might present the kind of surface your eye would bounce right off and move on.

Don’t let it! Because as it turns out, DeForge’s actual comics, as contained in these two issues, are straightforward, funny, and sharp as a knife. Inside, he wields a precise line to create character designs that read like a slightly more avant-garde version of what you might see on a post-millennial Nickelodeon cartoon. The storytelling and punchlines are always crystal-clear even as the material bounces back and forth between long-form, surreal horror stories and laser-precise gag strips. In the latter category, which mostly crops up in the first issue, DeForge uses anthropomorphized dogs and the superheroes of the Justice League to skewer the foibles of college students and their immediately post-graduation counterparts with laser precision. (Dog #1: “Lately, I don’t even know if I enjoy walks.” Dog #2: “You’re overthinking it. Did you finish The Wire yet?”; Green Lantern: “Things have been crazy for me lately”. Batman: “Is that why we’re spending League money on art school?!” Green Lantern: “We all voted on that, Bruce! We all voted!“)

The longer stories fruitfully work that horror-comedy sweet spot a lot of young cartoonists are mining these days, a great thrill to me because the comedy tends to actually be funny, and the horror black as midnight. In issue #1, a cartoon conscience rebels against God after being sent to dissuade yet another comics artist from suicide, only to be sentenced to a Hell inhabited by cartoon characters and their creators. What starts as a lampoon of art-comics culture every bit as successful as the college stuff veers into nightmarish action-horror territory as our hero narrowly, and I mean very narrowly, escapes evisceration and ritual sacrifice at the hands of two former funny-animal characters whose appearances have devolved into monstrous deformation and shadow. In issue #2, virtually all the page space is devoted to a long and no-fucking-around nasty horror story about a little kid who manages to domesticate a large spider whose brethren are simultaneously ushering in a quite lethal and disgusting plague-style demise for his uncaring family and abusive classmates. Imagine Skyscrapers of the Midwest weaponized and you’re almost there.

With these two issues–cogent in conception, confident in execution, and surely just an early step in a promising stylistic evolution–DeForge has landed himself on my must-watch list. Give ’em a shot, see if he lands on yours.

Comics Time: Wally Gropius

June 4, 2010Wally Gropius

Tim Hensley, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, May 2010

64 pages, hardcover

$18.99

Wally Gropius is more than just the main character of Tim Hensley’s elaborate and arch parody of ’60s teen-comedy and child-billionaire comics–he’s more like the language it’s told in, or better yet the font it uses. Hensley arranges him in poses whose pantomime exaggeration recall the primary mode of body language in any given Archie comic, but always in some bizarrely off-model and angular variation thereof. His pipe-like arms and legs, his clasping, grasping, pointing hands, even his squinting eyes and trapjawed mouth and flattened cranium (his hair color says “Archie Andrews” but his skull says “Dick Briefer’s Frankenstein”) all conspire to make him as much a pictogram as a person. Watching him and his equally gangly, geometric cohorts stretch and sprint and smash their way across Hensley’s brighly colored backgrounds and block-lettered sound effects is like reading your favorite poem–or even, as we see in a panel that became my Rosetta Stone for the book, Wally Gropius itself–as translated into a language with a totally different alphabet. What you know is in there, somewhere, but to use a frequently repeated line from the book, you just can’t quite put your finger on it.

Hensley pulls off a similar switcheroo with the writing itself. Instead of the instantly dated “hip” slang used by the middle-aged men who wrote the comics that Wally Gropius uses as a springboard, he subs in a nonsense patter that apes the self-assured argot of the plutocracy. Whether it’s Wally’s oblique strategies for his beloved Jillian Banks’s recording session (“You really almost had it there, but it’s still kind of teal. Can you sing it with a bit more cadmium?”), Wally and Thaddeus’s simultaneously ratcheted-up and abstracted fight over dating (“But, Dad, I wanna be a lothario speedwagon. Troubadours don’t submit to picture brides. They engage in felching with awestruck camel toe.” “Again with the CAMEL TOE! My own son!”), or the frequent direct references to finance and industry (“Petroleum is the seat of the soul,” “What good is Mammon if one can’t purchase reliable athmosphereic conditions?” “Wally, will you please clean your room? There are far too many denominations about.”), I can’t help but hear echoes of the ouroborosian discourse, cocksure and utterly divorced from reality, that led the economy off a cliff.

And wonder of wonders, the book finds its own way to be really funny amid all these highfalutin hijinks, and often in a direct, even lowbrow way. Obviously anyone who’s read this stuff has gotten a kick out of the sound effects, from the slamming bank-vault door that goes “TRUMP!” to Wally vomiting up a bellyful of money with a “HEAR$T!” The thing is filled with eyeball kicks like that, my favorites being the library bookshelf filled top to bottom with Tom Clancy, the baseball-stadium jumbotron sponsored by Summer’s Eve, and the Buddhist monk lighting himself on fire next to a placard that reads “U.S. OUT OF NORTH AMERICA.” There’s a diarrhea joke, there’s a cameo from an ’80s pop-culture icon, and there’s an incest sequence that is one of the most shocking, hilarious, perfectly paced things you’ll read all year.

“Well, Mom, what does it say?” asks Wally over a memorable shot of a disemboweled bird from whose entrails his mother hopes to divine the future. (Of course, we never get the answer.) I think you can figure out what Wally Gropius is saying, provided you keep in mind the combination of confidence and impenetrability that Hensley hits on so memorably in both writing and art. The tale’s in the telling.

Comics Time: Monstrosity Mini

June 2, 2010Monstrosity Mini

Jorge Diaz, writer/artist

self-published, 2009

12 pages

Free

Read it under the title Special Report at JorgeComics.com

There are pros and cons to be found in this one. Let’s start with the pros. As Alan Moore understood when constructing the punchline for his big shaggy-dog joke at the superhero genre’s expense, the giant-monster horror/sci-fi subgenre is ripe for comedic exploitation, not in the sense of creating funny-looking Mighty Morphin Power Rangers-style creatures, but in the sense of “How the hell does something of that size and disposition appear out of nowhere, anyway?” Cartoonist Jorge Diaz milks the most out of that “no one expects the Spanish Inquisition giant monsters!” idea by piling one on top of another in this brief teaser for his longer Monstrosity anthology: an irradiated meteor creates one giant monster, our military response to that giant monster attracts two more giant monsters from outer space, our military response to those giant monsters unleashes another giant monster from a parallel dimension, and we deliberately unleash still another giant monster to combat the first three. Meanwhile, those giant monsters are, in turn, a “Squirrelzilla,” two massive alien environmentalists, a skeletal fish-god, and a giant hummingbird summoned by two tiny, elderly Japanese former-schoolgirls. It’s all cockamamie, but no more cockamamie than, well, any giant-monster movie or comic you’ve ever seen. Meanwhile, the story is presented in recap by a harried news anchorman in a deadpan recitation that further emphasizes the ridiculousness of it all–as does the material’s presentation in this tiny minicomic, which shrinks each TV-monitor panel down to a meticulous-looking grid and serves as an ideal showcase for Diaz’s tight, cartoony line and design work.

The cons, by now, might be obvious to you–most so, “Squirrelzilla” and two giant alien environmentalists just aren’t that funny a pair of gags. Nor is the plot’s resolution, which involves luring the beasts to a Monster Island-type destination with sonic rhythms that cause them to hump each other. It’s broad stuff, overly so. But by contrast, the design for the giant hummingbird is both funny and strong–its tail twirls off behind it in strands, casting off stars and hearts and other beautiful illustrative super-kawaii filigrees. So too is the design of the diminutive, antennae’d Japanese ladies who summon him, all stooped shoulders and wrinkled, benevolent faces. The image of a giant fish skeleton wreaking havoc manages to be both amusing and genuinely weird. There’s also a great throwaway panel of a herd of elephants dancing in line thanks to that sonic frequency thing. In essence, the more Diaz tries to nail down very specific ideas and images rather than playing to the cheap seats, the better he both looks and reads.

Comics Time: Mr. Cellar’s Attic

May 31, 2010Mr. Cellar’s Attic

Noel Freibert, writer/artist

Extreme Troglodyte, April 2010

12 pages

$6

Buy it from Closed Caption Comics

Although that little jpg might get the idea across, you really need to hold the cardstock covers of Closed Caption Comics member Mr. Freibert’s latest horror-comic throwback to see how beautifully screenprinted those colors are. It seriously looks like he sat there and did it by hand with pastel colored pencils. The thinness and shakiness and uniform weight of his linework only further reemphasizes that Mr. Cellar’s Attic was an act of drawing, something that came out of the tip of a pencil or pen held by a person. Which, now that I think of it, is maybe how Freibert is able to reclaim the hoary EC Comics/Edgar Allen Poe/”Colour Out of Space” proto-body-horror tropes he’s working with out of the realm of cliche and make them feel like a force to be reckoned with again. In addition to the cool, clever wordplay of the title, Freibert’s pacing keeps things feeling fresh and lively and present, if you will. There’s an uneasy sense of discovery as Freibert’s guilty-conscienced narrator recounts his ill-fated decision to rent out his attic room to an elderly grotesque, whose personal hygiene and mysterious conduct gets worse and worse until the story culminates with the narrator’s inspection of the room he rented…and the smaller room he built inside it. That’s a great, weird image, and what is found inside that room doesn’t disappoint either. The thing ends with a gorgeously colored shot that all but demands Vincent Price be resurrected to provide his trademark cackle as its soundtrack. If you want a comic that utilizes the tools of today’s artcomix aesthetic to evoke the sensation you got when you were a kid looking at the awesomely hideous masks in the grown-up section of the Halloween store, you know where to look.

Comics Time: Big Questions #14: Title and Deed

May 28, 2010Big Questions #14: Title and Deed

Anders Nilsen, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, May 2010

50 pages

$7.95

Buy it from Drawn & Quarterly

You know how on The Sopranos, it was always the penultimate episode of the season that had the big climax? This is the penultimate issue of Big Questions.

I know I’ve got Lost on the brain this week, and it’s largely with that show in mind that I re-read all 14 issues of Nilsen’s anthropomorphized allegorical avian opus to date. Much more so than do the Vertigo-type series with which you’ll see the occasional facile comparison, Big Questions serves up a similarly intoxicating, dread-tinged cocktail. Flawed characters are buffeted by forces beyond their comprehension, who in turn have just as little control over their own destinies. Violence is ever-present, shocking and exciting when it erupts, devastating in its aftermath. Story seeds planted years ago (Big Questions has been running since 1998!) suddenly blossom, entangle, and collide, in this issue most of all. Of course the “big questions”–about the limits of our understanding, about the point of being here at all–are asked, if rarely answered. An overall high-quality visual presentation makes it all the more inviting, while individual images, like the one that graces this issue’s cover and the constituent parts of the harrowing sequence that precedes it, burn with the fire of the surreal and stick in the memory, giving your thoughts on the overall series something to coalesce around like coral. You’ll laugh, you’ll cry. Only instead of an attractive multinational cast, this one has birds.

My hunch is that when the fifteenth and final issue arrives, Big Questions will be looked at like Black Hole or the Jimmy Corrigan issues of Acme Novelty Library, both for the magnitude of the undertaking and the magnificence of its execution from top to bottom. I read a lot of good comics; this is a great comic.

Comics Time: Held Sinister

May 26, 2010Held Sinister

Conor Stechschulte, writer/artist

Closed Caption Comics, June 2009(?)

32 pages

I don’t remember what I paid for it

I’m coming up empty, but maybe you can buy it from Closed Caption Comics

I’ll tell you what, I wish I could find a link at which you could buy this comic, because if you enjoy the rough-edged alt-art-horror comics I talk about on this blog all the time? Dude, run, don’t walk.

Stechschulte’s art is rough in the extreme, a scribbled mess of thick blacks that nonetheless coheres into something palpable and easy to parse. It reminds me a bit of when I was a kid and I’d scribble one continuous line on a page for a long time, and then go back and highlight the figures and shapes I’d unwittingly drawn in the process. It’s not that manic, but that’s the general idea. It’s a great way to convey claustrophobia and barely contained desperation, which is what our main character experiences as he anticipates and then experiences what is apparently a monthly encounter with a sinister, supernatural visitor–a doppelganger carved from shadow itself. It’s a cool little story, a dark fairy tale or a lost piece of Poe, distinguished by a strong fight sequence, complicating details like the place a body gets stuffed, and a convincing air of inevitability and despair. I wish someone would put together an anthology of horror comics like this. I’d read the shit out of it, and if you care about horror in comics, you would too.

Comics Time: Snow Time

May 24, 2010Snow Time

Nora Krug, writer/artist

self-published, 2010

12 pages

I don’t remember what it cost, but I remember it wasn’t cheap

How I love little arty morality plays. Hot-shit illustrator Nora Krug follows up her ambitious Red Riding Hood Redux project–probably my big find for MoCCA 2009–with this short, achingly lovely to look at story of weather and murder. Like Red Riding Hood, Snow Time hides some rough stuff beneath its pretty surface, this time around telling the story of a man whose mother’s suicide has left him with dangerous abandonment issues. None of this is made clear until the middle of the story, after which the man’s apparent delight and attention to the snowman he’s built in his front yard in the middle of a weeks-long spate of snowstorms takes on a new (albeit only implied) punchline quality, and it’s a refreshingly chilling one. (Pun intended, but seriously, the image it implies through one quick panel of the snowman melting is sticking with me.) Snow Time is also an exercise in getting rich, sumptuous green-blues and manila-yellows to not just sit on a page, but radiate off of it, the way you can feel cold coming off of something metal. It ends with a tableau of grim discovery that reminds me of Taxi Driver of all things. It was worth the coin.

Comics Time: The Mystic Hands of Doctor Strange #1

May 21, 2010The Mystic Hands of Doctor Strange #1

Keiron Gillen, Peter Milligan, Ted McKeever, Mike Carey, writers

Frazer Irving, Frank Brunner, Ted McKeever, Marcos Martin, artists

Marvel, March 2010

48 pages

$3.99

I’ve read enough Hellblazer to understand the appeal of an anthology-style series of self-contained stories about a sorcerer jumping ugly with the dark supernatural and coming out on top, but at a price. John Constantine himself, though, is not for me. The spiked hair and stubble and cigarettes, the rumpled trenchcoat and English curses…obviously that’s cool with a capital C for many people, but it’s just not a set of character descriptors I can get terribly invested in. I think my favorite Hellblazer stuff I’ve ever read was a Jamie Delano thing back when he had longish wavy hair and spent the arc in jeans and a clean white t-shirt.

Doctor Strange, on the other hand? Oh yes indeed. People like NeilAlien and Tom Spurgeon have made much more convincing cases on behalf of the once and (hopefully) future Master of the Mystic Arts than I could ever do, but I’ll simply say that he’s a collection of images and ideas that I really like when they’re all smushed together. I like his big high-collared cloak, the Eye of Agamotto, his goatee/gray-temples combo, his Steve Ditko hands and Steve Ditko psychedelic vistas, his Greenwich Village lair that’s got more mysterious rooms than you’d find in its official floorplan, his pal Wong, his origin as the world’s biggest dickhead who suddenly realizes what a worthless tool he is when his hands get broken in a car wreck and he can no longer be a hot-shit surgeon, his vision quest in the Himalayas, his gorgeously designed enemies like Dormammu and the Mindless Ones, the idea that he’s constantly fighting against so many massive threats that neither the other heroes nor civilians could ever possibly appreciate the magnitude of his gig, all those great gibberish names and epithets Stan Lee cooked up for him to invoke, his highfalutin speech pattern derived from years of study of the most esoteric subjects imaginable, and on and on and on. I understand why the strictures of Marvel’s publishing model with respect to its superheroes probably prevents this, but a largely continuity-free solo Doctor Strange series in the vein of Hellblazer? I bet a small but loyal audience would be there for every issue, in large part because a large and loyal number of writers would love to sweep in for an issue or an arc and tell the one Doctor Strange story they’d always dreamed of telling, and an equal number of artists would wanna give their Ditko chops a major workout. I’d be there with ’em.

And lookee here! One of a series of pulpy ’70s-style black-and-white one-shot anthologies featuring stories about some of Marvel’s rough’n’readier characters (we’ve also seen War Machine and Ares), The Mystic Hands of Doctor Strange is (wait for it) just what the Doctor ordered. I was entertained as the dickens by all four tales contained herein, for all the reasons I enumerated above.

I think my favorite take on Strange here comes from Kieron Gillen in the story that kicks off the book. Sure, it doesn’t hurt that he’s working with the awe-inspiring Frazer Irving, who was born to draw Doctor Strange’s world. (He was also born to work in color, and you can feel him wanting to–for god’s sake it’s a Doctor Strange story set in the hippie era–but I’ll take what I can get.) But I was intrigued by Gillen’s conception of magic as a sort of cosmic whodunit, where when something’s going down, the Doc must figure out who had the means, motive, and opportunity to do it…in an arena where none of the rules of cause and effect, physics, or human behavior with which we are familiar are necessarily operative. In both the Gillen/Irving and Milligan/Brunner stories, there’s a final twist that emphasizes Strange’s self-martyrdom, his willingness, whether through necessity or weakness, to do some bad thing that will hurt him to get the job done. It’s really only he who gets hurt in the process, though, which is what separates him from your run-of-the-mill anti-heroes. When the Sorcerer Supreme crosses a line, he’s the only collateral damage. That’s what makes him the Sorcerer freakin’ Supreme, you know?

While the first two stories are period pieces set in the same timeframe as the publication of Marvel’s original black-and-white magazines, the second two are different. Ted McKeever’s one-man showcase of scratchy, angular blacks and weirdo creature designs–yep, that’s our Ted!–is a timeless tale, in which a devastated Doctor Strange roaming around on an alcoholic bender nevertheless encounters a demon and a benevolent spirit and learns an important lesson about his sorcery…which is exactly the kind of thing that should happen to a Sorcerer Supreme on an alcoholic bender. (I like to believe he’s discovering hidden knowledge when he’s on the shitter, even.) The final story is a short prose piece by Mike Carey in the style of an early 20th century weird adventure, featuring an impressively evocative Frazetta Death Dealer-style antagonist, a simplistic but effective take on mind over matter, a grin-inducing tease of Doc’s archenemy, and a pair of killer spot illos from Marcos Martin, including one that’s almost Paul Pope-ish in its riotous kinetic energy.

All told, it’s as an effective a disquisition on what makes Doctor Strange worth making comics about since Martin and Brian K. Vaughan’s memorable miniseries The Oath–perhaps even moreso, since while that series was clearly an attempt to say “See? Doctor Strange still works!”, this one-shot feels like it was constructed with that basic proposition never once in doubt. I got from it precisely the modest but indubitably pleasurable pleasure I wanted. More like this, please.

Comics Time: Weathercraft

May 19, 2010Weathercraft

Jim Woodring, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, April 2010

104 pages, hardcover

$19.99

Wow. And you thought Wilson was mean-spirited!

Part theater of cruelty, part joyous liberating revolution, Jim Woodring’s freakishly beautiful Weathercraft is at once the most direct and most elliptical of his Frank comics that I can remember reading. In its pages, Manhog, the half-human half-pig character who’s the Frank-verse’s avatar for the physical side of the id in the same way that funny-animal Frank represents consequences-be-damned curiosity and leisure, is made to physically suffer like you’ve seen few comic-book characters suffer before. Yet due to circumstances just as beyond his control as the passion he’s put through, this trauma leads him to an enlightenment that defies the spacetime continuum as he channels his newfound understanding into righting wrongs small and large. Yes, the cosmic reset button is hit at the end–this is a Frank comic after all, and it needs must remain static just as the Krazy/Ignatz/Offisa Pup triangle does. But until then, you’ve got a comic that’s both so confrontationally visceral and brutal that I almost put it down a couple of times, and one that’s such a visual and narrative strange-geometry dodecahedron that I compulsively read all the jacket copy upon finishing the comic just to make sure I had the first clue what the hell had just happened.

I think perhaps the most underrated weapon in Woodring’s artistic arsenal–certainly the one that had the greatest and most unexpected impact on me in this book–is, of all things, his panel borders. As you picture a Woodring Frank comic in your head, you’re probably seeing those wavy, buzzy lines that comprise his backgrounds, looking like a mosquito in your ear sounds; or perhaps those overripe plant-animal-mushroom-deity hybrid visuals, which explode the narrative at regular intervals. Unless you were paying specific attention to them, my guess is that if you were asked to describe Woodring’s panels, you’d say they were wavy themselves, maybe even prone to the baroque. But lo and behold, they are rigorously ruled rectangles and squares; on any given page, their borders are the thickest line to be found. I know I’ve written in the past that the presence of panel borders makes it difficult for comic horror to infect your nightmares; I still think that’s true, but in the moment, they can have–as they do here–an almost subliminal effect on your reading experience. No matter how woozily psychedelic each image here is, those big thick blocks tell you that something heavy is happening, something scary and indelible. Even in a Frank story; even in a Frank story where the characters’ nemesis Whim–that evil grinning guy who looks like a cross between Old Scratch and the moon-faced guy from those old McDonald’s commercials–reveals his all-powerful true self like the Sentry in Siege #3 and melts the reality of his enemies; hell, even in a Frank story in which a pair of new characters who look like something out of Stephen King’s Dark Tower series play Dark Tower-style games with the very fabric of their fictional world’s reality–even in stories like those, those panel borders communicate “Not a hoax! Not a dream! Not an imaginary story!” It makes Manhog’s torment all the more awful, and his triumph, however fleeting, all the more awesome.