Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

Comics Time: The Airy Tales

August 18, 2010The Airy Tales

Olga Volozova, writer/artist

Sparplug, 2008

128 pages

$15

Like some of the other Sparkplug titles I’ve sampled–Inkweed comes to mind–The Airy Tales, Olga Volozova’s collection of original short fairy tales and fables, is a tough sell at first glance. And as I’ve often said, first glance is precisely where I buy or pass. There are too many comics and too few hours in the day to force myself to plow through a book I don’t find appealing on an art-surface level. Every once in a while an imprint will come along whose guiding aesthetic, and this is nobody’s fault, simply has little Venn-diagram overlap with mine. First Second is one; Sparkplug seems at times to be another. But then for whatever reason–usually because I’m up against a self-imposed deadline and the book looks short enough to read on the train– I’ll say “What the hell,” take it off the shelf, give it a read, and exit gladder for having done so.

Such is the case with The Airy Tales. Like Inkweed, its visuals aren’t really too my taste. Volozova’s shaky line and mixed media elements come across a little bit Stieg, a little bit Salazar, and a lot alien from where I’m at. The painted colors read craft-y rather than considered, the character designs are too wishy-washy to stand out the way the great illustrated children’s-book characters do, and the placement of captions in particular is a detriment to readability. It’s clear Volozova’s intent is to combine the sequential storytelling of comics with the static image-and-text approach of a child’s storybook, but her solution–placing the text in little boxes surrounding the central image that are sometimes read from top to bottom and sometimes read from left to right–is confusing even to someone who got his altcomix start with Acme Novelty Library.

This leaves the writing to do most of the work–and it works. I really have to hand it to Volozova for capturing the ineffable quality of fairy tales before Disney simplified them into plucky can-do adventures. The recurring images bear the mark of springing unbidden and unexplained from her underbrain, whether it’s giant celestial birds using tiny threads thousands of miles long to guide each individual human around the Earth or a man made of rain who uses his godlike powers of growth to make the lives of the people who come to him for help just slightly better than before. Most of the time you get the sense that there’s some moral to the story, but it’s a, well, weird moral, a moral based on the moral-ity of an age or society lost to us. Like, there’s this one extended fable about a group of people who each live on a different leaf of a tree that sheds those leaves every day, only for them to drift back onto the tree each night. All the residents have full lives except this one guy whose sole possession is a bright yellow sweater; since his leaf isn’t burdened with family members or fun stuff, he ends up higher on the trunk every day, and his neighbors get jealous. Finally he catches on and deliberately builds a contraption to lower himself down to their level, and they’re all finally happy, and you think it’s a crabs-in-the-pot-type parable about how livin’ free means living outside society, or whatever. But then the story ends by telling us only the yellow-sweater man knew that in fact the leaves were never gonna re-attach to the tree again, because of the impending snowfall–and then the snowfall comes and each snowflake contains a little kid or animal cub. And that’s it! That’s the end. As Zak Smith recently said, the wonderful thing about Wonderland is that it makes you wonder; The Airy Tales certainly left me scratching my head. It’s alien from me in both the bad way and the good way.

Comics Time: Curio Cabinet

August 16, 2010Curio Cabinet

John Brodowski, writer/artist

Secret Acres, April 2010

144 pages

$15

I’ve been writing about the similarity between the horrific and the sublime for (God help me) over a decade now, but its rare for me to come across a comic that makes that connection as frequently and as subtly as John Brodowski’s Curio Cabinet. While reading it I located squarely in the increasingly rich contemporary alt-horror tradition–the deformed figures and soft pencils of Renee French, the heavy-metal/D&D imagery of Lane Milburn, the mostly wordless narratives of (to my delight!) almost too many talented horror cartoonists to list. And yes, there’s even the de rigeur cat-torturing scene. But only in flipping through the book in preparation to write this review did I realize just how many of Brodowski’s short, creepy stories end with their alternately hapless or horrifying protagonists gazing into a vista of vast natural or even cosmic splendor. Two separate characters who have very different nature-based obsessions both end up immersed in the great outdoors, staring off into the distance–as does a lake monster after unleashing its full destructive power on a battlefield. Two other characters–one the victim of a monster-induced car wreck, the other none other than Jason Voorhees–become a part of titanic outer-space tableaux: Jason is cradled by his mother Pieta-style in the sky, the accident victim welcomed into the embrace of a colossal dog-god. Several stand-alone images, most memorably a series of illustrations from the old anti-Semitic myth cycle of the Wandering Jew, take on a similarly ecstatic, transcendental feel. The message is both troubling and comforting: It implies a connection between the individual horrors we experience and the very fabric of existence, yet it also suggests that perhaps an enlightenment is possible whereby this waking nightmare can be appreciated, if never fully understood. More like this, please.

Comics Time: A God Somewhere

August 13, 2010A God Somewhere

John Arcudi, writer

Peter Snejbjerg, artist

DC/WildStorm, June 2010

200 pages

$24.99

As the co-writer and by all accounts driving creative force behind the Hellboy spinoff series B.P.R.D., John Arcudi is responsible for what amounts to the best ongoing superhero series on the stands. A God Somewhere is not on that level. Which, as was the case with Wednesday’s review, is perfectly fine–few things are. Moreover, much of what makes B.P.R.D. so effective is tied into just how long it’s been going on. We’ve had years and years to get acquainted with and grow attached to its characters and the neuroses they bring to their long, losing war with the paranormal–to say nothing of the ever more baroque mythology of that war itself. By contrast, A God Somewhere has to get us to care about its central quartet of characters–brothers Hugh and Eric, their best friend Sam, and Hugh’s wife Alma on whom Sam has long harbored a more-than-crush–and their paranormal plight–Eric mysteriously gains powers that make him the world’s only superhuman, but which very rapidly drive him Doctor Manhattan-style crazy in such a way as to make him the world’s only supervillain–in the space of the equivalent of four issues.

It does this mostly through shorthand. Racial and religious issues are presented in the didactic style of a Law & Order episode (or, well, a superhero comic). Plot drivers are cribbed liberally from universal superhero touchstones like Watchmen or the Incredible Hulk TV show. The creators operate under the assumption that the audience is already familiar enough with once-innovative ideas for the subgenre–Superman as Christ figure; superpowers would “really” drive a normal person into bloodthirsty madness–to take them as read. In short, it can feel rushed, even clumsy–words you’d never associate with the laconic, precision-calibrated existential action-horror-black-comedy of B.P.R.D.

But the same intelligence and willigness to discomfit that Arcudi brings to that title shows up here, even if it’s forced to fight against the constraints of the shorter format. Flashbacks that enrich our understanding of the characters and their complex quadrangle start and stop with almost Jaime Hernandez-like suddenness, with only a change in panel-border color to differentiate them from the main action, which boasts equally fanfare-free jumps forward through time. The violence is in the over-the-top True Blood-level splatter mode of similar work in Powers and Invincible, but contains enough disturbing detail, largely through the familiar sub/urban setting of some of the worst bloodbaths, to lodge in the brain and curdle in the gut. There’s at least one plot twist so unexpected and awful I didn’t even understand what I was looking at until it was made clear a couple pages later. The degree to which Arcudi is willing to leave what’s going on inside Eric’s head a mystery, allowing him to speak only in transparently faux-profundities like what Sam calls “a crazy, mass-murdering Buddha,” is refreshing and a bit haunting. Peter Snejbjerg’s warm, round character designs–his stuff here reminds me a lot of Richard Corben’s Hulk comic Banner, and not simply because of the shared subject matter–are undermined a bit by uncharacteristically bland, brown-town coloring by Bjarne Hansen, but these are still people it’s pleasant to look at even when what’s going on is super-unpleasant. Is it the landmark that the effusive blurbs from Mike Mignola and Denny O’Neil make it out to be? No, but I would argue that that’s not the intention, either. It feels to me more like an exercise: a bunch of ideas about character and concept that Arcudi wanted to try out. Even if it’s not entirely successful, that exercise was a worthwhile one.

Comics Time: Fandancer

August 11, 2010Fandancer

Geoff Grogan, writer/artist

self-published, August 2010

36 big-ass pages

$20

This isn’t quite the knockout blow that was writer/artist Geoff Grogan’s last full-length mixed-media comic, Look Out!! Monsters. And believe me, that’s totally fine–without that out-of-nowhere book’s shock-of-the-new impact, its follow-up, Fandancer, was never gonna hit that hard. But from that stunning cover, perhaps my favorite of the year, on down, it’s definitely a hit. A sort of feminine yin to LO!!M‘s Frankenstein-by-way-of-Jack-Kirby masculine yang, Fandancer (loosely) tells the story of a superheroine we join mid-plummet from an exploding plane, harried by her Bizarro-style nemesis until she hits the water below. Then we appear to be transported backwards, first to the womb and then to some dawn-of-time confrontation between a nude woman and a male interloper who reveals himself as a goat-headed devil before stealing the suddenly very pregnant woman’s embryo/glowing-life-force-thing, eating it, and then restoring her to life as an afterthought. Then (I think) the superheroine whose (I think) origin story we’ve just seen comes to in the water, and through a series of collages involving vintage comic and advertising art, outer-space vistas, and hysterical dialogue cribbed alternately from romance and superhero comics, we trace (I think) her journey into the underworld lair of her male bedeviler, whom she subsequently defeats in cartooned combat. The book ends with a close-up of her face, the life-force back in her possession.

Or maybe not, I don’t know. The story, to the extent that there is one–and in the cut-up/collage section, who the hell really knows–isn’t important. What is important is the dazzling art from Grogan, in a variety of styles: primary-color Kirby pastiche, loose and gorgeous red-and-gold-and-blue crayon, the startlingly effective reappropriated collage material which appears to be tweaking all the usual suspects in that arena, from Lichtenstein to Spiegelman to Glamourpuss-era Sim. No matter the style, man oh man does all of it work hella well on the oversized pages Grogan’s working with here, with really stellar paper stock production values to boot–each flip of the page is an eye-popping pleasure. And as in Look Out!! Monsters, what emerges most clearly from the deliberately elliptical and allusive storytelling is a sense of struggle, of great inner beauty under traumatic assault from great inner ugliness. (Don’t get it twisted, there’s some funny stuff in here, too–I’m pretty sure one collage page is actually a sex scene, and figuring that out made me laugh out loud.) My sincerest hope is that Grogan keeps putting out a book like this every couple years, Ignatz Series-style. (The format’s very similar, if that helps you picture what’s going on here.) I’ll be back for all of ’em.

Comics Time: Cyclone Bill & the Tall Tales

August 9, 2010Cyclone Bill and the Tall Tales

Dan Dougherty, writer/artist

Moonstone, 2006

232 pages

$16.95

Fictional comic stories about music are often not just bad, but embarrassingly, infuriatingly bad. I’m not sure why this is, to be honest. I think the answer may be found in noting the tendency of stories about obscure/failed/garage/shitty bands/music (e.g. Jaime Hernandez, Gipi, Bryan Lee O’Malley, Makoto Yukimura) to be much much better than stories about famous/successful/stylish/supercool bands/music (you can probably rattle off the names of several such failed series from the past five years, easy).

First, the roundabout explanation. When you’re tackling music just as a thing people do out of compulsion or enjoyment, independent of external payoff, that’s universal. But when you’re approaching music as something that makes its practitioners that much more awesome than everyone else, you invite your readers to compare your depiction of that awesomeness to what they, personally, find awesome about the music they find awesome. And when that comparison clashes–as it often does, because rock-star hero worship is an enormously personal thing, millions of idiosyncratically intimate relationship established with fantasy figures–it’s throw-the-book-out-the-fucking-window time. The book ends up feeling…like a costume, a disguise, not like an outfit. (Weirdly, I don’t think this rule applies as neatly to movies as it does to comics. Maybe it’s because movies have an inherent glamour to them that comics don’t, so they can address the glamour more naturally, I don’t know. I really like Eddie & the Cruisers, is what I’m saying.)

But a more direct explanation would simply be “show, don’t tell.” In my experience, comics-about-music that pivot off the involved parties’ coolness tend to absolutely bury the reader in LOOK HOW COOL THIS STUFF IS!!!!isms, which is death for coolness in fiction as it is in real life. (Seriously, people who think Geoff Johns lays on the Hal Jordan hero worship too thick in Green Lantern need to get back to me after reading any recent series that invokes the British rock tradition in any way.) You don’t see the flopsweat when reading about the misadventures of Sex Bob-omb or La Llorona–they just do what they do, and that’s why it works.

Cyclone Bill & the Tall Tales falls somewhere in the middle, in large part because of what an odd, odd book it is. I stumbled across one of the single issues while working at Wizard, in a pile of the “well, somebody out there’s readin’ it, I guess”-type comics that tended to accrue here and there. It’s done in a painted, grey-tone black-and-white style that really does have more in common with alternative comics than “indy comics” of the sort you might expect from a publisher whose bread and butter is the randomest bunch of licensed properties you can imagine. (Kolchak the Night Stalker!) Writer/artist Dougherty’s work here is undoubtedly the work of a young cartoonist–it’s stiff at times, unequal to the tasks he sets for himself (like the first-person POV videotape mockumentary storytelling device that recurs throughout) at others–but there’s also much to admire and enjoy, from the attractive character designs to the stark, angular, expressionist overall look.

Moreover, the story boasts gratuitously weird elements galore. The nominal protagonist, documentarian Margarita Bloom, spending what seems like half the book asleep on the couch. Cyclone Bill, the titular guitar god whose untimely onstage murder (yep, it’s that kinda deal) is the center of the story, is a classically trained prodigy from Poland who toured the great halls of Europe before disappearing to become a Catholic priest or something, then reemerging as the second coming of Jimi Hendrix after plucking an undistinguished American bar band out of obscurity and joining them as their lead guitarist. Dougherty even casts himself and his real-world bandmates as main characters–Bill’s band, the Tall Tales. It’s all really quite singular, especially because Dougherty has left this sort of comic behind–he now does a humor strip about a coffee-shop clerk with a web page done in Comic Sans. Then as now, my first thought upon looking at this book is “Where the heck did this thing come from?”

This is not to say that the story doesn’t traffic heavily in traditional signifiers of cool, because it does. It’s the sort of comic in which a recreation of the famous photo in which Johnny Cash flips off the camera is used as a major plot point, if that helps. But in the main, it’s trafficking in such a hoary, out-of-fashion brand of rock and roll coolness that it’s practically gone all the way around to uncool again. Robert Johnson at the crossroads, Elvis Presley still haunting the highways of the Great American Nowhere, sinister significant others in the Yoko Ono role, a slogan-spouting punk as the antagonist, deals with the Devil in which souls are sold for rock ‘n’ roll, a celestial gathering of dead rock stars…this is your father’s musical mythmaking. Yeah, I cringed a little when Freddie Mercury, Kurt Cobain, John Lennon, Jim Morrison, and Elvis Presely teamed up to kick Satan’s ass around Graceland, but not as much as I’d have done had Jarvis Cocker been involved, you know? It’s far enough away from where I am not to clash so violently.

No, it’s not the Velvet Goldmine of comics I’ve long hoped for–a story that’s both reality-warpingly personal in its approach to the musical icons it’s dealing with, but also accessible enough to people who aren’t the creator to reveal something about the music and musicians involved, and entertaining enough for that not even to matter. But it is Doughterty laying it all on the line in terms of his love for a certain rock and roll tradition, fashion be damned, and that’s admirable in its own way. It’s a fictional comic about music that didn’t make me want to light it or myself on fire by the end, which is an achievement in and of itself.

Comics Time: The Witness

August 6, 2010The Witness

Hob, writer/artist

self-published, 2008

24 pages

$3

Comics about death, even good comics about death, are a dime a dozen.. Comics about death where the character that dies is biologically incapable of understanding what has happened to it? And in which the entire world dies, completely and irrevocably, taking all hope of future life with it? Rarer, and thank goodness, because I don’t know how many comics like this one I could take without cracking. This is not to say that the artist otherwise known as Eli Bishop’s “ghost story” about a dinosaur whose spirit lingers on Earth, occasionally interacting with its inhabitants (both alive and dead) until the solar system’s destruction billions of years from now by the expanding sun, is morbid or grim beyond the needs of the subject. Something about his airy, elegant line–able to convey the weightlessness of the dino-ghost and to accrue background detail without bogging the image down–prevents The Witness from ever feeling dreary or didactic. But that’s just it: This casual acceptance of the death of all things, a post-life eternity that just spirals on and on and on and on and on and on without ending, ended up being much more chilling to me than most stories about shuffling off this mortal coil. I’ve thought about my eventual expiration enough that doing so is like meeting a familiar friend. But death without the possibility of thought, by you, by anyone or anything else? That’s a stranger at the door and I’m afraid to let him in.

Comics Time: Prison Pit: Book 2

August 4, 2010Prison Pit: Book 2

Johnny Ryan, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, July 2010

116 pages

$12.99

“OPERATION: RAPE LADYDACTYL. BEGIN.”

It wasn’t until I read those words on the screen of a computer operated by a robotic antagonist of Prison Pit‘s main character Cannibal Fuckface that I realized just how far Johnny Ryan was going to go with this series. Obviously it was already beyond violent; obviously it was already beyond sexually vulgar as well, what with Volume One’s maggot-fellatio fade-out. Obviously Volume Two was already filled to bursting with literally nauseating body-horror transformations and mutilations brought to life (and death) by Ryan’s never better, never nastier pen art. But an extended sequence in which our anti-hero is forced against his will to hunt down, attack, maim, and graphically rape-murder a creature that’s distinctly female even for all its monstrousness, one that screams in agony…for the first time I realized that Prison Pit isn’t a fusion-comics exploration of awesomeness in all its forms, but a horror-comics exploration of awfulness–of violence that maims and kills not just body but soul. Ryan is willing, even this early in a series I imagine will be able to last as long as he wants it to, to completely invert his instantly-iconic warrior, to make the audience root against him desperately, to feel dick-shriveling revulsion at his violence and pity for his victim. “That fucking sucked,” CF says when it’s all over. Understatement of the year. This book is a masterpiece of awfulness.

Comics Time: Exit Wounds

August 2, 2010Exit Wounds

Rutu Modan, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, 2007

168 pages

$16.95

What a lovely-looking book Exit Wounds is. Rutu Modan’s skillful take on the Clear Line style elicits strong “performances” from her characters, creates an inviting depth of field, and holds her frequently sumptuous colors quite well. Her staging is rarely as dynamic as that cover image, but when it is, hoo boy, fabulous stuff. Overall I feel like she’s doing with the Clear Line what Emmanuel Guibert tried but failed to do in an inkier style: Take real life and gradually subtract detail until what remains is paradoxically even livelier.

The story? Eh. It’s your basic alternative-comics “young person’s personal epiphany enabled by unexpected, brief, intense, difficult relationship with other young person” story, a template established by the likes of I Never Liked You, Black Hole, and Ghost World, gone supernova with Blankets, and since utilized to varying degrees of success by Adrian Tomine, Danica Novgorodoff, Blaise Larmee, Paul Hornschemeier, Dash Shaw, Hope Larson, Bryan Lee O’Malley, the Tamaki sisters cousins, Natsume Ono, Inio Asano, and so on and so forth. This particular variation is uninspired and, literally, unsurprising. When their personalities clashed; when they fell into an uneasy rapport that slowly grew into an easy one; when they argued and made up; when they staved off emotional disaster by having ill-advised sex; when they stormily split up; when they capped off the book with a highly symbolic interpersonal act–each of these elicited a “yep, that’s pretty much what I expected” from me.

The affair is sprinkled with light commentary about Israel’s social, economic, ethnic, and denominational stratification. It’s subtle, thoughtful stuff, focusing on the way that both the state’s inherent construction and its predicament vis a vis its neighbors and occupation-ees constantly juts into people’s personal lives in mostly quiet, mostly unpleasant ways. That and the sumptuous art is probably what got the book over with so many readers and critics. But to me, it’s a little like getting a molten chocolate cake with no molten chocolate inside. It’s not quite a hollow experience, like one of those chocolate Easter bunnies where it’s just a thin layer of yummy and then a lot of air–the cake is substantial and sweet. But without the molten chocolate that a less predictable, more alive story would provide, you still feel like something’s missing.

Comics Time: Paper Blog Update Supplemental Postcard Set Sticker Pack

July 30, 2010Paper Blog Update Supplemental Postcard Set Sticker Pack

Anders Nilsen, writer/artist

self-published, November 2009

16 pages, 7 postcards, 1 sticker

$10.95

A slice of history here: This minicomic/postcard set/collection of beautiful drawings of bird heads labeled with names like “Beyonce,” “Mister Peanut,” and “Paul Wolfowitz” contains the very first of Nilsen’s “Monloguist” strips. Monologues for the Coming Plauge, Monologues for Calculating the Density of Black Holes, The End, and even Nilsen’s blog itself wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for the first few strips in which blacked-out stick figures spoke dialogue jotted down during Nilsen’s conversations with friends on a trip to Switzerland. (“I think it’s bad, looking at the ass. I don’t mean spiritually, either,” says a figure I’m reasonably sure is Sammy Harkham.) It’s fascinating to see how rapidly all the tics and tropes that have made this style of Nilsen’s so quietly haunting develop: the blacked-out mistakes, the seemingly random distortion or deconstruction of the Monloguist, the sudden shifts from banal observations and list-making to gaze-into-the-abyss despair and back again. But the illustration work included here, including a fascinating postcard image of a deer and some boulders nestled in the strange branches of some bizarre alien-looking tree, offer ample evidence of the raw chops with which Nilsen complements his experimental zeal. I dare say that if you send any of the postcards to anyone, you’re liable either to get married or never hear from them again. A fascinating little package from a serious best-of-his-generation candidate.

Comics Time: The Comics Section from the Panorama

July 28, 2010The Comics Section from the Panorama

(aka The San Francisco Panorama Comics Section)

Keith Knight, Jon Adams, Michael Capozzola, Gabrielle Bell, Daniel Clowes, Ivan Brunetti, Alison Bechdel, Gene Luen Yang, Art Spiegelman, Ian Huebert, Adrian Tomine, Chris Ware, Kim Deitch, Seth, Erik Larsen, Jessica Abel, Heather Brinesh, Katrina Ortiz, Carson Ellis, Jon Klassen, Jon Scieszka, Adam Rex, Mac Barnett, Jenny Traig, Kevin Cornell, writers/artists

McSweeney’s, March 2010

18 pages

$10

Everything’s coming up newsprint! Originally included with McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern #33–the “McSWEENEY’S HEART NEWSPAPERS” project The San Francisco Panorama–and now conveniently sold separately because McSweeney’s knows its audience, The Comics Section hews pretty closely, intentionally or not, to its conception as a newspaper’s funny pages. There’s that same lack of a unifying aesthetic or visible editorial hand, that same variety in tone and quality, and that same presence a strip or two that leave you totally baffled. How does it work as an argument for the preservation of the newspaper as a format? Jimmy crack corn and I don’t care. I’m not here for the Wednesday Comics-style newsprint nostalgia, I’m here for the comics. And the strong ones are strong enough that I don’t mind having spent the necessary scratch.

Look, Ware and Clowes just tower over this thing, let’s get that established right away. Ware’s centerfold spread is a luscious thing, with those bright blue and pink colors he used for the cover of Acme #19 and an inviting assortment of strips about young-brainiac-turned-adult-divorcee Putty Gray and his enamorata Sandy Grains. You can start pretty much anywhere on the spread, flip the thing in pretty much any direction, just letting your eye go where it wants and reading accordingly, and it works. (Compare and contrast with Alison Bechdel’s tribute to the game of “Life,” which forces you to rotate the entire broadsheet with seemingly every panel to little discernible aesthetic effect and much upper-arm exhaustion.) As you might expect, several of the “punchline” panels here are real punches to the gut; I’ll never get enough of Ware’s sense of “humor,” the way he just puts despair where the jokes would go. Ditto Clowes, whose provides the section’s opening salvo, a nasty little science-fiction spoof called “The Christian Astronauts” with as funny and fuck-you of a final panel as anything in Wilson.

There are two other stand-out strips in the section. Kudos to Adrian Tomine for writing a strip about a superhero named Optic Nerve that’s just an out-and-out autobiographical satire of how badly comment threads comparing him to Daniel Clowes get to him and how all things considered he’d probably rather be hanging out with his wife than wasting his time in this thankless field. He doesn’t care if navel-gazing and superhero satire are the two things most likely to get your brand of alternative comics ridiculed on the Internet these days, you know? That’s what he wants to do, and dammit, that’s what he’s doing. And it’s funny! And kudos to the Editors for thinking to include Erik Larsen, of all people: He uses his Savage Dragon character for a light superhero satire at least as effective as Tomine’s, and it’s clear from inking, coloring, and choreography that he simply cares a lot about cartooning, which makes a two-page broadsheet spread arguably an even more effective showcase for what he does well than an ongoing series well into the 100s. And now that I think of it, I liked Seth’s page as well. The more I see of his stuff, the more the disconnect between his in-real-life look, his ruminative pacing, and his slick cartooning intrigues me rather than puts me off.

The rest? Eh, I can take it or leave it. Mostly leave it, I suppose–I don’t know why Kim Deitch laid out his story basically backwards, I don’t know why Jessica Abel’s adventure-strip pastiche selected a relatively inert portion of the adventure to depict, I didn’t think very many of the non-full-page strips (Knight, Adams, Yang, Brunetti) were funny at all. But then, for years, I only read The Far Side.

Comics Time: Neighbourhood Sacrifice

July 26, 2010Neighbourhood Sacrifice

Steph Davidson, Michael DeForge, Jesjit Gill, writers/artists

self-published, 2009

12 pages

$2

See sample images and buy it from Michael DeForge

Bam bam bam bam bam–with each turn of the page, this cheap newsprint zine hits you with a powerful image as big as the trim size will allow. The images–a quick google search for the artists’ homepages reveals I’m out of my element at trying to deduce who did what based on their other work, for the most part, though I think I at least recognize DeForge when I see him–are tailored for maximum impact. Maximum awesomeosity, if you will. You’ve got DeForge’s trademark slimy monsters, seemingly constructed out of bits of thousands of other beasts–like if Shub Niggurth were made of her 1,000 young. You’ve got massive, realistically drawn altars laden with occult and Egyptian kitsch. You’ve got a guy looking into the mirror to see a melted-faced monstrosity staring back at him; turn the page and another guy’s cutting his cubist-looking face in half with a sword. Heck, the thing opens with a pretty hilarious selection of newspaper comic titles given DeForge’s heavy-metal typography treatment. (My favorites are Ziggy, which uses a sword for the “i” in the style of The Legend of Zelda, and Hi and Lois, whose letters are used to form a grinning skull.) It’s a delirious, this-goes-to-eleven experience, over almost as soon as it begins.

Comics Time: Scott Pilgrim Vol. 6: Scott Pilgrim’s Finest Hour

July 23, 2010Scott Pilgrim Vol. 6: Scott Pilgrim’s Finest Hour

Bryan Lee O’Malley, writer/artist

Oni, July 2010

248 pages

$11.99

Or: Scott Will Eat Itself. The gist of this final volume in Bryan Lee O’Malley’s worlds will live/worlds will die/comics will never be the same series is that it’s an extraordinarily bad idea to reduce the people in your life, even the people who used to be in your life, to stock roles in the beat-’em-up videogame or shonen manga you’ve mentally conceived your life to be. Not only is this cruel and reductive to them, not only will it cause them trouble to the extent that you’re still in their lives and forcing them into that role when you interact, it’s cruel and reductive to you yourself, since it traps you in the corresponding role as well.

I mean, I guess that’s the gist. I’ve always had a hard time connecting with Scott Pilgrim on the personal, emotional level a lot of its ardent admirers do, mostly, I think, because I’m a creep. As I put it when discussing Vol. 5:

There’s no doubt that I’m speaking from my own experience with my own emotional life, which for whatever reason I don’t experience as a lot of rock and roll fun with the occasional bummer mixed in, even if that is in fact a more objectively accurate view of what my life has been like. Maybe it’s just a preference thing, maybe I feel like darker material more accurately reflects what is important/lasting in life/art, I don’t know. I do know that I don’t see my life as a rollicking adventure, or more accurately, something that might be a rollicking adventure were the occasional metaphorical robot fight thrown in.

The long and the short of it, especially in a volume such as this, which wraps up an entire series’ worth of emotional arcs in the form a massive, bloody (!) swordfight, is that Scott and his friends are characters whose adventures I can enjoy even if I can’t personally really understand the thought process underneath them. Like, look, O’Malley’s art has never been better than it is in this volume, which is pretty much true every time–the climactic fight scene occupies about two-fifths of the book and has oomph galore, and I think O’Malley deserves some sort of special Eisner Award for the potential Envy Adams cosplay opportunities created here. And it’s difficult to overstate the subspace corridor opened in my head over these past few years by his overall mix-and-match aesthetic, from its non-traditional, designy use of captions and text to tell the story, to its no-explanations mix of romance and action, to his often laugh-out-loud funny dialogue and sense of timing, to most especially his incorporation of videogame tropes–just a vast reservoir of completely underutilized visual vocabulary and storytelling potential. So if, in the end, Scott Pilgrim isn’t my life, I sort of feel like the last thing Scott Pilgrim would want is for me to pretend that’s the role it played.

Comics Time: King-Cat Comics and Stories #69

July 21, 2010King-Cat Comics and Stories #69

John Porcellino, writer/artist

Spit and a Half, September 2008

28 pages

$3

In the right hands, comics don’t depict, they convey. This is the advantage they have over their cousin film. The basic stuff of film (putting aside animation and abstract filmmaking and CGI for the moment) is, on a fundamental level, the recording of things that actually happened in front of the camera recording them. Those recordings can be recordings of a fiction, and they can be used to construct a fiction, and directors and cinematographers and editors and composers and effects technicians can add their interpretive gestures, but film is nevertheless a hegemony of fact. Comics, by contrast, is all middleman. Even an autobiographical comic is by virtue of being a comic not showing you something that happened, but telling you about it, the telling coded directly into the line of the artwork. It’s a gestural art form, a mime medium.

No one gets that better than John Porcellino. Most lo-fi autobio cartoonists, perhaps paradoxically, aim for maximalist effect in terms of presenting the artist’s self-conception: shaky, rough-hewn lines, clumsy character designs, everything designed to get across “I’m self-effacing!” Porcellino stays out of his own way. With his smooth uniform line weight, characterized by elegant curves and semicircles, he presents information on a need-to-know basis, usually emphasizing human figures against a minimally depicted background (like a sky) or foreground (like a car window). He’s not conveying a pose, he’s conveying in-the-moment relationships: Between himself and his wife, between his two cats, between himself and a parking lot, between the grass and the sky. This happened, yes, but he allows you to draw the conclusion yourself–this is how it happened, this is how it felt in that moment. All that empty space allows you to place yourself between those lines. The effect is immediate, immersive, and evocative, so that when the poetic writing really hits–especially those frequently powerfully sad final lines–you can all but feel that world’s weight around you.

Comics Time: Batman R.I.P.

July 19, 2010Batman R.I.P.

Grant Morrison, writer

Tony S. Daniel, Lee Garbett, artists

DC, 2010

224 pages

$14.99

Here’s a quick list of fun things found in this immensely enjoyable comic:

* Opening a story called Batman R.I.P. with a splash page which reads “YOU’RE WRONG! BATMAN AND ROBIN WILL NEVER DIE!”

* A bunch of weird supervillains from around the world sweeping into Gotham City to take it over as a joint venture

* Batman coming home from a long night of crimebusting to bang his gorgeous model/aristocrat girlfriend

* Robin thinking that’s kinda weird

* The Joker drawn as a nightmarish cross between the Thin White Duke, a Cenobite, and bell hooks

* Bruce Wayne’s girlfriend methodically explaining away the majority of the Bat-mythos as signs of debilitating mental illness

* Graffiti shutting down Batman’s brain

* A hunchback and a bunch of guys dressed like gargoyles pounding the snot out of Alfred with clubs

* Batman embedding within himself a back-up personality just in case his regular personality is in some way compromised

* Said back-up personality making a multi-colored costume for itself out of garbage and then running around braining villains with a baseball bat

* The central clue/metaphor being revealed as a pun on the femme fatale’s skin tone and hair color

* Said femme fatale’s leering facial expression when her villainy is revealed

* An impeccably choreographed martial-arts battle between Robin and a killer mime from France

* Villains who are all drawn look like they’re having the time of their lives until the precise moment Batman and his friends arrive to kick their asses, which they in turn are drawn to look like they were born to do

* Doctor Hurt repeatedly referring to himself as Doctor Thomas Wayne and no one believing him

* Jezebel Jet saying “What’s that sound?”–cut to a silent panel of her plane being swarmed by an army of Man-Bats

* Ending with a two-issue Lynchian psychogenic fugue induced by New Gods from Apokalips that simultaneously reincorporates the goofy old Batman adventures from the Silver Age and presents a bunch of shoulda-woulda-coulda alternative realities and ends when a chainsmoking orange person shoots a giant psychic lump of clay repeatedly because Batman has proven too awesome to psychically pirate and clone

Comics Time: Mome Vols. 17-19

July 16, 2010Mome

Vol. 17: Winter 2010

Kaela Graham, Rick Froberg, Paul Hornschemeier, Tom Kaczynski, Dash Shaw, Laura Park, Olivier Schrauwen, Michael Jada, Derek Van Gieson, Sara Edward-Corbett, Renee French, Ted Stearn, Kurt Wolfgang, T. Edward Bak, Josh Simmons, writers/artists

Vol. 18: Spring 2010

Kaela Graham, Nate Neal, Lilli Carre, Dave Cooper, Gavin McInnes, Ben Jones, Frank Santoro, Jon Vermilyea, Ivan Brun, Joe Daly, Ted Stearn, Nicolas Mahler, Tim Lane, Conor O’Keefe, Michael Jada, Derek Van Gieson, T. Edward Bak, Renee French, Jon Adams, writers/artists

Vol. 19: Summer 2010

Kaela Graham, The Partridge in the Pear Tree, Josh Simmons, Olivier Schrauwen, Gilbert Hernandez, D.J. Bryant, Tim Lane, Conor O’Keefe, Robert Goodin, T. Edward Bak, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds, Gary Groth, editors

Fantagraphics, 2010

Vol. 17: 120 pages

Vols. 18-19: 128 pages each

$14.99 Each

Now that’s more like it!

Last time I checked in with Fantagraphics’ flagship anthology series–well, you could say one of two things about it: 1) That it lacked focus, or 2) that what it was focusing on just wasn’t remotely my cup of tea. Overly familiar underground schtick, humor pieces that didn’t make me laugh, whimsical work that lacked urgency and oomph, an overall identity crisis caused at least in part by high turnover among an ever-expanding line-up…Whatever it was, it bummed me out as someone who’s read the book from the get-go (and submitted to it a couple times!), and often forcefully advocated for it as the best buy in alternative comics not despite but in part because of the varying quality of the contributions, which enables you to directly observe the difference between what works and what doesn’t.

Now, though? It’s back in business. You can mostly credit the newer crop of contributors, a rough and tumble bunch who are bringing some fierce and hard-edged work to the table. Jon Vermilyea’s guest-artist turn in BJ and Frank Santoro’s Cold Heat-verse is brining out the funny, monstrous, horny, creepy side of that franchise more than ever before. Tim Lane’s nasty, Burnsian blend of noir and slice-of-life harkens back to the altcomix material that first made you uncomfortable when you first drifted over to the wrong side of the comics shop a decade and a half ago. Michael Jada is harnessing Derek Van Gieson’s sooty, watery black-and-white images to a tough-as-nails World War II story, of all things. Olivier Schrauwen has submitted his two best contributions thus far: a journey into the colonialist heart of darkness, and a C.F.-evoking tearjerker about the fantasy life of a man in a waking coma. Gilbert freaking Hernandez guest stars with a Roy story that’s good at everything Beto’s ever good at: character designs, dark skies, body language. Josh Simmons continues making a name for himself as one of the best in the biz with the start of “White Rhinoceros,” a cringingly funny cross between Alice in Wonderland and a Mel Gibson phonecall, with some of the best coloring this side of The Dark Knight Strikes Again. Robert Goodin returns with an impeccably drawn story of Carl Jung’s religious awakening, complete with giant god-shit falling from the sky and crushing a cathedral. Newcomer D.J. Bryant submits a story of a crumbling marriage that’s nasty in more ways than when–it’s straight-up porn, and good porn at that. And thanks to some perfectly evoked body language in an illo from Rick Froberg, Bryant’s story isn’t even the first memorable depiction of cunnilingus in these three issues!

I’m not on board with everything, of course. Paul Hornschemeier’s “Life with Mr. Dangerous” concludes as uneventfully as it’s continued; I’m an admirer of Hornschemeier’s work and it’s always lovely to look at, so I’m gonna reserve judgment for the eventual collection, but having that story wrap up feels like a welcome farewell to what Mome used to be. T. Edward Bak’s historical comic about the naturalist Georg Steller showed promise at first, but I’m thrown by the awkward way he breaks sentences mid-phrase from panel to panel or even page to page, and a story like this needs all the smooth-storytelling help it can get. Conor O’Keefe’s work is gently gorgeous to an almost ridiculous degree, but I’ve got no “in” to his whimsical world of boy-men in nightgowns. Nicolas Mahler’s amusing autobiographical anecdotes are the very definition of “nice, nice, not thrilling, but nice.” Much as I love seeing comics from Dave Cooper, his Pip & Norton stuff with Vice co-founder Gavin McInnes has always been his weakest. I’m equally cold on another comic duo, Ted Stearn’s Fuzz and Pluck. And the less said about Nate Neal here, the better–his two-page takedown of “hipsters,” for Christ’s sake, presents itself as though thousands and thousands of people haven’t spent the last decade doing exactly that (did you know they are pretentious? did you know they buy ugly clothes at vintage stores? did you know they live in Williamsburg? good lord) and is easily the most embarrassing thing that’s ever made its way into a Mome. (Which reminds me–it’s an anti-hipster piece in an alternative-comics literary journal. I feel like Elaine Benes shouting at toupee-wearing George Costanza when he refuses to date a balding woman: “You’re bald!”)

But the balance is definitely in favor of the strong stuff, because it is strong stuff–well drawn in a variety of styles, and potentially troubling without cloaking itself in shopworn tropes. Even the work that’s sort of middle-of-the-road in terms of the reaction it got from me has its moments, from the physical mechanics of the swamp creature Sara Edward-Corbett draws to the doll-like character designs and dramatic angles of Ivan Brun’s rather on-the-nose story of gun violence Jon Adams’s weird mash-up of Chris Ware fanfic and Stephen King short story. Once again, you’re getting your bang for your buck.

Comics Time: The Troll King

July 14, 2010The Troll King

Kolbeinn Karlsson, writer/artist

Top Shelf, April 2010

160 pages

$14.95

Like the work of some kind of less violent altcomix Clive Barker, Kolbeinn Karlsson’s The Troll King is a defiant, love-it-or-shove it celebration of monstrousness, queerness, and the dreamlike Venn diagram overlap between the two. The burly beasts who inhabit the forest just beyond the glow of the city lights in this suite of interconnected stories have, through “hard work” and because society is “not worthy of [their] presence,” created a world for themselves, a world of their own, a world where their “bodies” and their “pleasure” are their “first priorities.” In this place, the creatures are stocky, broadly designed, miraculously self-perpetuating species, evoked with a wavy, almost furry line and bright, flat colors for an overall effect that wouldn’t look out of place in a Kramers Ergot tribute to Super Mario Bros. 2. Appropriately, events proceed with demented video-game (or dream or drug-trip–both adjectives made literal at points during the book) logic–a man they rescue from the river, for example, is transformed via sexual congress with the titular monarch into a “noble steed” upon which the Troll King flies to the Moon. I’m not saying there’s no horror or loss in this world, because there’s plenty of both: Our two main characters have twins, whose coming-of-age story involves coming to terms with death, yearning for something they can’t get with their cozy family inside the forest’s borders, and eventually turning on the parents who love them so much; there’s also a batshit violent “Wild West” interlude/shamanic vision that demonstrates the way community can break down and tease out the worst aspects of humanity (however broadly construed) as a counterpoint to the way the forest creatures’ world seems to bring out their best. But (and again like Barker) Kolbeinn is giving his gay utopia an edge: It embraces the lived experience warts and all. Freedom, like the panel where the Troll King and his noble steed fly to the moon (itself part of perhaps the most affecting sequence of comics I’ve read all year), is overwhelming and scary, which is part of what makes it so wonderful in the first place.

Comics Time: pood #1

July 12, 2010pood #1

Geoff Grogan, Kevin Mutch, Alex Rader, editors

Sara Edward-Corbett, Kevin Mutch, Fintan Taite, Tobias Tak, Lance Hanson, Henrik Rehr, Adam McGovern, Paolo Leandri, Mark Sunshine, Bishakh Som, Andres Vera Martinez, Chris Capuozzo, Hans Rickheit, Jim Rugg, Brian Maruca, Connor Willumsen, Geoff Grogan, Joe Infurnari, writers/artists

Big If, April 2010

16 big giant newsprint pages

$4

Simply existing is pood‘s greatest victory. It’s one thing for Alvin Buenaventura or Dave Eggers to provide the alternative and art-comics canon a Little Nemo-sized canvas on which to play; it’s quite another for this idiosyncratic, even weird, group to get a shot. (Why, only three contributors have been published by Fantagraphics!) And as I’ve said in the past, I happily rescind my initial doubts about the newsprint/broadsheet format: It’s the only way the project would make economic sense, first of all, and second of all it ends up holding line and color rather impressively–I’m not sure Sara Edward-Corbett’s work has ever looked better on the page, for example, and Tobias Tak and Geoff Grogan sure do turn in some lush purples.

Beyond that? The victories are harder to come by, I think. I mean, I’m generally perfectly happy with the main throughline of artcomix today, so on that level, folks who follow their bliss in other, perhaps more underground-y directions are gonna have a harder time fitting in with me, too? A handful of stories make use of the giant page to tell impressive little done-in-one morality plays–there are not one but two Western-vengeance stories, a muscular black-and-white firecracker by Andres Vera Martinez and a delicate, sinister color piece by Connor Willumsen, and I think they’re the highlights of the collection, while Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Kirby-indebted slice-of-lifer lingers as well. And I’m a sucker for the “gigantic environment with cutaway spotlight panels” approach to telling a story on a page this size, as utilized by Tobias Tak and Bisakh Som, even if I’m not over the moon for the stories they’re telling with that technique. Finally, Mark Sunshine’s strip–really it looks like a book’s worth of strips smushed into one page–and its world of cartoon characters who believe their very existence could usher some change into the world they inhabit, Heisenberg-style, is baffling to me in a way that suggests it will linger as well. But much of this material is either goofier (Edward-Corbett, Grogan, Rugg & Maruca, Taite, Capuozzo) or surface-uglier (Mutch, Sunshine) than I’m able to get into, undercutting the potential power of making giant-ass comics. Even a couple of personal favorites, Henrik Rehr and Hans Rickheit, offer contributions that are pretty much just what they normally do, only bigger. It reminds me a bit of the early days of Mome, when I would go on about how the uneven quality of the contributions was actually a plus because you could do apples-to-apples comparisons of work that worked with work that didn’t–only here, nothing is quite rising to the level of “there, that’s how it’s done.” Still, pood #2 is on the way, and at that price it’s a no-brainer to take a flyer on coming back to see if the crew fulfills the promise of the format.

Comics Time: FCHS

July 9, 2010FCHS

Vito Delsante, writer

Rachel Freire, artist

self-published, 2010

128 pages

$15

MTV had this weird, late-night pseudo-telenovela/soap/anthology series called Undressed once. Each episode would feature segments from three separate stories–one was about high schoolers, one was about college kids, one was about young twentysomethings, and all of them were about fucking. You’d follow each story for, I don’t know what it was, half a dozen episodes? And the attractive young actors would have endearingly awkward shenanigans about whether or not to be fisted by their partner or losing their virginity or having a threesome or some such. It was cute and earnest and hot and addictive, and even though it could get pretty explicit it was also really sweet. That’s how I’d describe FCHS, too.

Operating out of the Batcave that is NYC retail mecca Jim Hanely’s Universe, writer Delsante and artist Freire have crafted an adorable, believable high-school soap set circa 1990. It’s got a couple of major things going for it. The first is Delsante’s scripting, a sort of easy-going casual banter that tends toward the economical as most comics writing must but never comes across like the presentation of an array of reactions designed to move the plot from point A to point B. Sex is on the mind of these kids all the time–which is perfectly accurate!. And while they discuss it with realistic cussing and matter-of-factness–and are even occasionally shown nude in the service of the material–it’s neither some porno smutfest nor a depiction of teen sex as some soul-crushing vortex of sordid desire. It’s something young people really like doing–just like playing in a band or playing football or jackassing around or eating tacos. Hooray for that! Indeed, that lighthearted tone carries over into the book’s very pacing: Delsante will skip right past relatively momentous events you’d expect a teen drama to hit hard, content to study the characters as they anticipate them and then react to the fallout instead. I wasn’t sure that would work, but it does.

The second selling point is undoubtedly Freire. The reason I compared the book to that weird MTV sex show is because, as was the case there, I could easily see myself casually watching these characters for months on end. Her kids are cute as buttons, sexy when they need to be and childlike when they need to be. Folks have compared it to the Archie house style, and rightly so, but while it’s just as easy to read and makes its characters just as easy to keep track of, it’s far less strident and played to the cheap seats. If Tim Hensley tweaked ’60s teen comics toward angry angularity in Wally Gropius, Freire dials it down to a sort of lush, gently stoned laid-back wave.

No, it’s not some Black Hole/The Diary of a Teenage Girl-style tear-down-the-sky cri de coeur on adolescence. I can understand how it might feel slight to some people, and I can understand how the laconic pace might make some folks shrug. But by the end I really wanted to see the rest of these characters’ senior year play out. Hopefully I’ll get the chance.

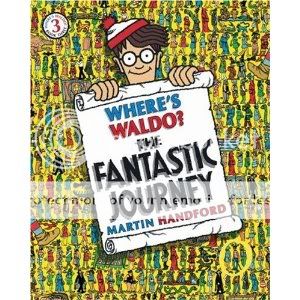

Comics Time: Where’s Waldo? The Fantastic Journey

July 7, 2010Where’s Waldo? The Fantastic Journey

Martin Handford, writer/artist

Candlewick, 2007 (this edition)

32 pages

$7.99

Buy all six Waldo books as a set for like $30

I didn’t give a lot of thought to comic art or illustration as a kid. Which in many ways means “mission accomplished” for the comics artists and illustrators I came across, I suppose. For readers that age, you want form to follow function–an exciting comic should look exciting, a funny comic should look funny. It wasn’t until I was much older that I was able to appreciate the books that had lodged in my head because their art did something more. The Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark series, illustrated by Stephen Gammell, was one example. Those pictures looked like the evil they depicted somehow leaked into the real world and corrupted the art itself.

The other big one, for me, was Where’s Waldo?, particularly this third volume in the series, which when I was a kid was called The Great Waldo Search. This is the one where Waldo travels through “the realms of fantasy,” as the slipcase of the six-volume set of Waldo books I bought for Christmas puts it, so that naturally put it more in my wheelhouse than the other two volumes that were available at the time I first came across it. And obviously Martin Handford’s loose, goofy character designs and slapstick sense of humor aren’t a world apart from the majority of cartoon art kids are offered. But what I found–and continue to find–so mesmerizing about this one is the way Handford conveys, in these eye-meltingly dense two-page spreads, a sense of permanent chaos. Each scene is a virtual (and in one case literal!) sea of jostling, arguing, fighting, laughing, playing, sleeping, eating, jumping, falling, flying, running, sliding, shouting, bodies. Streams of water, billows of smoke, rivers of fire defy gravity and snake around and through half a page. A single action causes a domino effect that brings dozens of warriors low. People celebrate a victory over the characters to their left, completely oblivious to the damage about to be inflicted on them by the characters to their right. Massive schemes to defeat rivals are always just on the verge of coming to fruition or heading for disaster. More than any other artist I can think of, Handford conveys a world of action, decision, coincidence and consequence within each image. You get the feeling that the conflagrations you’re seeing on each spread could last forever, an endless flow of action and reaction. In fact, the only other artist I know of who’s experimented with this sort of thing is Brian Chippendale.

And might there be a message in here, too? Fully half of The Fantastic Journey‘s twelve scenes involve armed conflict between rival groups. You can get lost in the maniacal detail and humorous quasi-violence of their battles for minutes on end, but an even larger part of their visual appeal is that the combatants are basically color-coded: Blue monks of water vs. red monks of fire, ferocious red dwarves vs. vaguely Asian knights who look like a weaponzied deck of Uno cards, evil black knights vs. green-skinned forest women, two enormous armies of dueling pastel knights, a posse of blue-uniformed monster hunters stalking their prey underground. The one exception pits villagers in rainbow-colored clothes against equally gaudy giants. A seventh spread involves four teams of ballplayers–blue, green, peach, and red–whose sport is just about as violent as any of the the actual battles. A state of obviously absurd conflict based on completely arbitrary distinctions? Come for the devilishly difficult puzzle aspect, stay for the impeccable visual satire.

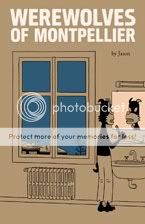

Comics Time: Werewolves of Montpellier

July 5, 2010Werewolves of Montpellier

Jason, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, June 2010

48 pages

$12.99

You have to be a real expert in Jason-character physiognomy to even be able to tell that the lonely expat main character in Werewolves of Montpellier is sometimes wearing a werewolf mask. After all, the guy’s an anthropomorphized dog at the best of times. In the end, that ends up being the gag. You’re not some uniquely unlovable monster, you’re just a guy with problems, like anyone else–like the woman you love, for example, who cultivates a studied air of Audrey Hepburn cool yet still can’t prevent her girlfriend from cheating on and then leaving her. The problem with the book’s titular antagonists, it seems, is that they’ve dedicated their entire lives to their big problem, and are willing to kill and die for it. The violence that results is as random and awful as it always is in Jason comics, but the overall message about how to handle it–get over it and move on–is delivered with uncharacteristic humorous bluntness. There’s no percentage in making yourself more alone than you have to be.