Posts Tagged ‘comics reviews’

Comics Time: “Flash Roughs/In a Hole: Jul-Aug 2010”

February 16, 2011“Flash Roughs/In a Hole: Jul-Aug 2010”

Matt Seneca, writer/artist

self-published on the web, February 2011

52 pages

Read it at Death to the Universe

Talkin’ ’bout his g-g-g-g-generation. When he’s not making comics, Matt Seneca is best known as a promising new critic of the things, one of the very few who have emerged on the internet over the past few years who engage with alternative and art comics with any regularity. He does this in post-post-post fashion. For starters, he’s part of the first wave of post-Comics Comics critics. Dan Nadel, Tim Hodler, and Frank Santoro could take the work done by Gary Groth and The Comics Journal in carving out a critical space for comics of genuine literary ambition and execution as read, enabling them to eschew the Journal‘s then-necessary ruthless aesthetic elitism and reclaim genre comics as a valid and fecund field for criticism. (At its best, the young comics blogosphere — and its print funnel, Dirk Deppey’s Comics Journal — did some of this work too, especially the inestimable Joe McCulloch, but I think the Nadel braintrust, through its multiple venues (CC, PictureBox, The Ganzfeld, Art Out of Time), really put it over the top.) In turn, Seneca exists in a world where the Journal‘s distinctions are a pretty distant memory, a world where in the wake of the CC crew’s rehabilitation project, genre work of whatever sort can be unhesitatingly and unashamedly examined with all the close-reading intensity and epiphanic emotion anyone ever brought to “The Death of Speedy Ortiz.” Seneca is also probably several years deep into the post-Internet cohort, a group that never saw print as the primary outlet for criticism or goal of its writers, a group that didn’t exist even five years ago. As such, personal critical interests, obsessions, and conundrums can be pursued with a length and an idiosyncratic focus unthinkable to any primarily-print writer (Kent Worcester excepted). Finally, he’s post-Tucker Stone/Mindless Ones/Noah Berlatsky, the performance-art superstars of Internet comics criticism. Though each of these writers (or group of writers in the Mindless Ones’ case) is very different, each embraces a style of writing and an approach to criticism that (for better or worse — which one really isn’t important here, however) makes them the star of the criticism as much as the work in question; I know this is old news in, say, rock crit, but in my experience growing up, comics critics, even the most outspoken ones, basically wanted to get out of the way of what they had to say about the comics they were talking about. The Mindless Ones’ Morrison-under-a-microscope rhapsodies, Stone’s insult-comic/battle-rap smackdowns, and Berlatsky’s indefatigable, Google Alert-enabled contrarianism all require readers to engage not just their analysis of and opinions on the work, but the way that analysis and those opinions are performed.

Not that anyone ever asked, but I’ve got some problems with all of this. I find that the focus on artsy genre stuff, or genre stuff that can be reinterpreted as artsy (Carmine Infantino?), can get monotonous (must every comic deliver thrills and sexy cool explosions?) and myopic (won’t somebody think of John Porcellino?) and lead to the lionization of some pretty middling work (like Brendan McCarthy’s dopey, weirdly racist Spider-Man: Fever). And I think the tendency to wax loquacious, coupled with the use of a given comic to put on a little show about lots of other things besides, can lead to some errors in interpretation and judgment because the error feels more right than what might result from a more rigorous interrogation of the work. Not every comic, and certainly not every cartoonist’s entire career, can be sussed out from a single panel in “as below, so above” fashion, and all the passion in the world can’t make The ACME Novelty Library #20 a work of life-affirming optimism or people’s discomfort with Ebony White in The Spirit comparable to idiots’ discomfort with the use of “nigger” in Huckleberry Finn.

So there’s that. Or maybe I just like shorter, more direct criticism. Maybe I just like reading about contemporary works that don’t feature extraordinary individuals solving problems through violence. Or maybe I would like to have been half the writer Seneca is at his age (my shit was pretty embarrassing) and had (or have! who knows?) half the audience he does, or would like to be able to convincingly make comics myself instead of just writing them and/or writing about them.

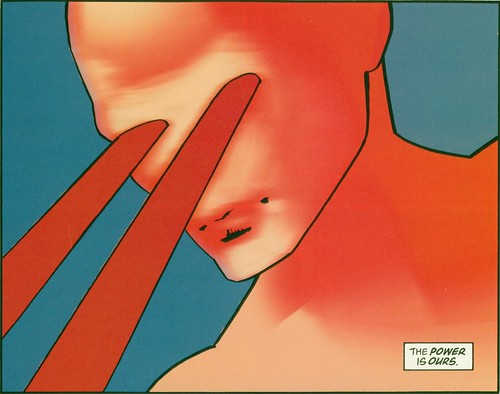

Point is, I brought a lot of baggage to “Flash Roughs/In a Hole: Jul-Aug 2010,” Seneca’s breakout work as a comics creator. In comics form, it synthesizes many of the features and factors Seneca brings to the table as a critic into art of its own. In fact, the comic itself is both comic and comics criticism: Interwoven with intensely confessional writing about Seneca’s break-up with his fiancée is astute, self-reflexive, process-based discussion of Seneca’s attempt to create a (bootleg, highly personal) comic starring the Flash, as well as passages about the sensual qualities of the work of Carmine Infantino and Guido Crepax delivered in more-or-less straight (albeit handwritten) prose. It feels like the logical place for Seneca’s criticism to go. Both style and emotional impact are such a big part of his critical writing; what better way to enhance both than making that critical writing into actual art that pleases the eye with its bright reds and yellows and bold hand lettering, that aims straight for the heart and gut with ripped-from-real-life doomed romance? Seneca knows his limits as a draftsman — that’s part of what the comic is about, his earlier self coming to terms with how his Flash comic was likely to look when he “finished” it and realizing that the “rough,” pencil-only version might make for more powerful comics — and compensates for it with eye-grabbing color and a welcome willingness to let words work as pictures. Much of this is done literally atop notes in Seneca’s sketch/notebooks — notes for the Flash comic, notes from the art class he was taking at a time; these bleed through and are pasted over in Brian Chippendale Ninja style. You’ll never feel bored reading this comic, never feel like your eyes or mind are being underfed, and this is one of the great strengths that artcomics, which need not meet any of the obligations of the representational, can bring to the table. Seneca, a voracious reader of comics, knows what he can do with the things.

And the same self-awareness he brings to craft concerns forms the lynchpin of the narrative: Knowing full well that we probably got there pages and pages ago, Seneca self-effacingly walks us through the achingly long time it took him to realize that the super-sexy, super-smart new character he’d introduced for his Flash comic wasn’t just a tribute to Crepax’s Valentina, but quite obviously and painfully to his increasingly estranged girlfriend as well. Once they break up, the comic is lost to him forever. Anyone who’s tried their hand at making art will recognize that feeling, that you’re often the last person to figure out what the art you’re making is about.

Even still, I’ve got my reservations about the comic — not so much what it’s about, but how it goes about it. Any work this profoundly personal and traumatic for the author makes those who find themselves unable to get fully on board feel like churlish heels, but c’est la vie: I think I’m past the point where I can appreciate doomed glamour. I don’t see anything glamourous about doom anymore. So when Seneca scrawls “WHEN LOVE LEFT MY LIFE” in giant block letters that take up nearly an entire page, or writes “SHE LEFT.” in white against a black block background, or fairly casually drops in some drug references, or ends on a lightly scrawled note of uplift centered against a blank spread, these things feel calculated for maximum Tumblarity to me, like a fashion photo of a pretty girl in a Joy Division t-shirt. (I am not immune to such things’ charms, to be sure! But that’s on me.) And the writing gets mighty purple in the big climactic (heh) pre-breakup “tonight’s the night, it’s gonna be alright” sex scene. Again, I’m not about to deny that this is how this felt to him in that moment, but sometimes in art as well as in criticism, you need to remove yourself from the equation. Of course, you could just as easily say that maybe I need to take my own advice.

Comics Time: The Dark Knight Strikes Again

February 14, 2011The Dark Knight Strikes Again

Frank Miller, writer/artist

Lynn Varley, colorist

DC, 2003

256 pages

$19.99

Buy it from Amazon.com

Originally posted on October 28, 2009 at The Savage Critic(s).

Years ago I came across an eye-opening quote from Jaron Lanier in the liner notes of the reissued Gary Numan album The Pleasure Principle. Google reveals that it was pulled from this Wired essay. Here’s what it said:

“Style used to be, in part, a record of the technological limitations of the media of each period. The sound of The Beatles was the sound of what you could do if you pushed a ’60s-era recording studio absolutely as far as it could go. Artists long for limitations; excessive freedom casts us into a vacuum. We are vulnerable to becoming jittery and aimless, like children with nothing to do. That is why narrow simulations of ‘vintage’ music synthesizers are hotter right now than more flexible and powerful machines. Digital artists also face constraints in their tools, of course, but often these constraints are so distant, scattered, and rapidly changing that they can’t be pushed against in a sustained way.”

Lanier wrote that in 1997. I’m actually not sure which vintage-synth resurgence he was talking about, unless you count the Rentals or something (although everyone and their grandfather was namechecking Gary Numan back then, which was sort of the point of including the quote in the liner notes. Maybe he meant Boards of Canada?).

But golly, it sure seems prescient now, huh? Here we are, in the post-electroclash, post-Neptunes, post-DFA era. The hot indie-rock microgenre is glo-fi, which sounds like playing a cassette of your favorite shiny happy pop song when you were three years old after it’s sat in the sun-cooked tape deck of your mom’s Buick for about 20 years. And my single favorite musical moment of last year, as harrowing as those songs are soothing, was the part of the universally acclaimed Portishead comeback album that sounded exactly like something from a John Carpenter film score. (It’s at the 3:51 mark. It’s awesome, isn’t it?)

And that’s just on the music end. Visually? Take a look at Heavy Light, a show at the Deitch Gallery this summer featuring a murderers’ row of video artist specializing in primary-color overload and technique that doesn’t just accentuate but revels in its own limitations. Foremost among them, at least for us comics folks, is Ben Jones, member of the hugely influential underground collective Paper Rad and recent reinterpreter of the massively mainstream The Simpsons and Where the Wild Things Are. But the ones with the widest cultural import at the moment are Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim of the astonishingly funny and bizarre Adult Swim series Tim & Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!. Their color palette is garish, their digital manipulations are knowingly crude, and their analog experiments are even more so. When they combine the three, god help us all. And let’s not forget Wareheim’s unforgettable, magisterially NSFW collaboration with fellow Heavy Light contributor and Gary Panter collaborator Devin Flynn.

Yeah, most of these guys are playing it either for laughs or for sheer mind-melting overload, but I think there’s frequently beauty in there to rival what some of the musicians are doing. (Click again on that first Ben Jones link.) And (thank you Internet God) this amazing video by Peppermelon shows that you can do action, awe, even sensuality with this aesthetic. The rawness, the brightness, the willingness to let the seams show–it all gives you something to push against again.

When I’ve written about The Dark Knight Strikes Again I’ve been fond of saying it was years ahead of its time. Sometime in the past week and a half or so, there was a day when I listened to Washed Out, then stumbled across that Deitch show link in an old bookmark, then watched an episode of Tim & Eric, then came across that Ben Jones WTWTA strip–and suddenly I realized I was right! Not that it matters–at all–whether or not Miller and Varley have any real continuity with any of this material. They certainly didn’t get there before Paper Rad, unless I’m wildly mistaken. But then half the fun of DKSA is spotting all the stuff Miller does, from naked newscasters to superheroes ruling the earth rather than just guarding it, seemingly without realizing someone’s done it first. What difference would that make? Meanwhile, in all the off-the-beaten-path references Frank Santoro has cited during the production of his Ben Jones collaboration Cold Heat–essentially a glo-fi comic book–I haven’t heard word one about this book. But I’m not saying Miller & Varley paved the way for anything. I’m saying that when Miller abandoned his chops (and, for the most part, backgrounds!) for the down and dirty styles he (thought he) saw at SPX, and when Varley decided to use photoshop to call attention to itself rather than to create a simulacrum of something else, they were using the same tools, tapping the same vein, seeking the same sense of excitement, discovery, and trailblazing as these newer movements.

I’ve also been fond of likening DKSA to proto-punk, taking a cue from Tony Millionaire’s jacket-wrap blurb: “Miller has done for comics what the Ramones et al have done for music. This book looks like it was done by a guy with a pen and his girlfriend on an iMac.” The idea is that it’s raw, it’s loud, it’s brash, it doesn’t have time for the usual niceties–it’s getting comics back to their primal pulp roots. I spoke to Miller several times during and following the release of the book, one time for print, and he said as much. (I certainly never would have bought the cockamamie idea that this thing was some sort of corporate cash-grab even if he’d never said word one.) He even mentioned to me his belief that the brightly colored costumes of the early superheroes served mainly the dual purpose of a) telling them apart from one another, and b) proving they weren’t naked, so even his thinking in historical terms had him ready to peel back from realism as a form of reclamation. And of course it’s not exactly like the story was at all subtle in this regard: Batman and his army came back to overthrow the dictators that kept us fat and happy and turned the superheroes into boring wimps. But ultimately the punk comparisons were just a little off. Born less of despair than of delight, filled less with anger than with joy, The Dark Knight Strikes Again anticipated a way of doing things that is not intended to look or sound effortless, that draws attention to its own construction, but which–with every pixelization and artifact, with every crayolafied visual and left-in glitch, with every burbly synth and sky-bright color–pushes against that construction and springs out into something wild and wonderful.

Comics Time: All-Star Superman

February 11, 2011All-Star Superman Vols. 1 & 2

Grant Morrison, writer

Frank Quitely, artist

DC, 2008-2010, believe it or not

160 pages each

$12.99 each

Buy them from Amazon.com

Originally posted on March 11, 2010 at The Savage Critic(s).

The cheeky thing to say about the brand-new out-of-continuity world Grant Morrison constructed to house his idea of the ideal Superman story is that it’s very much like the DC Universe we already know, but without backgrounds. Like John Cassaday, another all-time great superhero artist currently working, Frank Quitely isn’t one for filling in what’s going on behind the action. One wonders what he’d do with a manga-style studio set-up, with a team of young, hungry Glaswegians diligently constructing a photo-ref Metropolis for his brawny, beady-eyed men and leggy, lippy women to inhabit.

But, y’know, whatever. So walls and skyscrapers tend to be flat, featureless rectangles. Why not give colorist/digital inker Jamie Grant big, wide-open canvases for his sullen sunset-reds and bubblegum neon-purples and beatific sky-blues? We’re not quite in Lynn Varley Dark Knight Strikes Again territory here, but the luminous, futuristic rainbow sheen Grant gives so much of the space of each page–not to mention the outfits of Superman, Leo Quintum, Lex Luthor, Samson & Atlas, Krull, the Kryptonians and Kandorians, Super-Lois, and so on–ends up being a huge part of the book’s visual appeal. And thematically resonant to boot! Morrison’s Superman all but radiates positivity and peace, from the covers’ Buddha smiles on down; a glance at the colors on any given page indicates that whatever else is in store, it’s gonna be bright.

Moreover, why not focus on bringing to life the physical business that carries so much of the weight of Morrison’s writing? The relative strengths and deficiencies of his various collaborators in this regard (or, if you prefer, of Morrison, in terms of accommodating said collaborators) has been much discussed, so we can probably take it as read. But when I think of this series, I think of those little physical beats first and foremost. Samson’s little hop-step as he tosses a killer dino-person into space while saying “Yo-ho, Superman!”…Jimmy Olsen’s girlfriend Lucy’s bent leg as she sits on the floor watching TV just before propositioning him…clumsy, oafish Clark Kent bumping into an angry dude just to get him out of the way of falling debris…the Black-K-corrupted Superman quietly crunching the corner of his desk with his bare hands…Doomsday-Jimmy literally lifting himself up off the ground to better pound Evil Superman’s head into the concrete…the way super-powered Lex Luthor shoulders up against a crunching truck as it crashes into him…the sidelong look on Leo Quintum’s face as he warns Superman he could be “the Devil himself”…that wonderful sequence where Superman takes a break to rescue a suicidal goth…Lois Lane’s hair at pretty much every instant…You could go whole runs, good runs, of other superhero comics and be sustained only by only one or two such magical moments. (In Superman terms, I’m a big fan of that climactic “I hate you” in the Johns/Busiek/Woods/Guedes Up, Up & Away!) This series has several per issue.

And the story is a fine one. Again, it’s common knowledge that rather than retelling Superman’s origin (a task it relegates to a single page) or frog-marching us through a souped-up celebration of the Man of Steel’s underrated rogues gallery (the weapon of choice for Geoff Johns’s equally underrated Action Comics run), All-Star Superman pits its title character, directly or indirectly, against an array of Superman manques. The key is that Superman alternately trounces the bad ones and betters the good ones not through his superior but morally neutral brains or brawn, though he has both in spades, but through his noblest qualities: Creativity, cooperation, kindness, selflessness, optimism, love for his family and friends. I suppose it’s no secret that for Morrison, the ultimate superpower of his superheroes is “awesomeness,” but Superman’s awesomeness here is much different than that of, say, Morrison’s Batman. Batman’s the guy you wanna be; Superman’s the guy you know you ought to be, if only you could. The decency fantasy writ large.

Meanwhile, bubbling along in the background are the usual Morrisonian mysteries. Pick this thing apart (mostly by focusing on, again, Quitely’s work with character design and body language) and you can maybe tease out the secret identity of Leo Quintum, the future of both Superman and Lex Luthor, assorted connections to Morrison’s other DC work, and so on. But the nice thing is that you don’t have to do any of that. Morrison’s work tends to reward repeat readings because it doesn’t beat you about the head and neck with everything it has to offer the first time around. You can tune in for the upbeat, exciting adventure comic–a clever, contemporary update on the old puzzle/game/make-believe ’60s mode of Superman storytelling in lieu of today’s ultraviolence, but with enough punching to keep it entertaining (sorry, Bryan Singer). But you can come back to peer at the meticulous construction of the thing, or Morrison’s deft pointillist scripting, or the clues, or any other single element, like the way that when I listen to “Once in a Lifetime” I’ll focus on just the rhythm guitar, or just the drums. Pretty much no matter what you choose to concentrate on, it’s just a wonderfully pleasurable comic to read.

Comics Time: Various pieces by Uno Moralez

February 9, 2011Various comics and illustrations by Uno Moralez

Uno Moralez, writer/artist

self-published, 2011-

Read them for free at UnoMoralez.com

I’ve been struggling mightily to put my finger on what the art and comics of Uno Moralez remind me of. I got that he draws the faces and figures of his characters to evoke that weird frisson you get when you see commercial illustration from other cultures, where what’s perfectly normal in (say) Eastern Europe or the Indian subcontinent or Southeast Asia or Central America looks just slightly off-kilter and disconcerting to us. And I got that he paces his horror comics with the attention to narrative economy and rhythm of a dark Nick Gurewitch. (That comic about the kid and his telescope gave me panicky giggles with each subsequent reveal.) And I got that there’s a massive, in-your-face dose of kink and smut, tying it to similar traditions in Japanese illustrations and comics and also reinforcing that “I shouldn’t be seeing this” feeling. But that weird, glitchy computer drawing style — what is that all about? Then it hit me: It looks like a black-and-white version of the still images they used as cut scenes in old 8-bit Nintendo games. It feels wrong to apply that aesthetic to these horrific images and stories; and because the style is so mechanical, it’s a wrongness that feels as though it has settled into and infected the very digital medium conveying it — the computer equivalent of Pim and Francie‘s Golden Age animation studio gone horribly wrong. Put it all together and you’ve got one of the most impressive and fully formed horror aesthetics I’ve seen…well, since Michael DeForge, I suppose, coupled with that same “whoa” factor I got from the format and pacing of Emily Carroll’s brilliantly assembled “His Face All Red.” Jeepers creepers, does this person hit my buttons.

(Via Zack Soto via Jillian Tamaki via Ryan Sands)

Comics Time: Squadron Supreme

February 7, 2011Squadron Supreme

Mark Gruenwald, writer

Bob Hall, Paul Ryan, John Buscema, Paul Neary, artists

Marvel, 1985-1986 (my collected edition is dated 2003)

352 pages

$29.99

Buy it used from Amazon.com

Originally posted on August 10, 2009 at The Savage Critic(s).

I don’t know what it is about Squadron Supreme, but I seem to read it only during times of great personal trauma. I first read the book in 2003, during my wife’s hospitalization at a residential treatment facility for eating disorders. I have vivid memories of sitting at a nearby Panera Bread between visiting hours, slowly turning the pages. And as I reread the book over the past couple of weeks, an 11-month period during which my wife suffered two miscarriages was capped off by the news that one of my cats has a chronic immune-system disease, complications from which prevented him from eating; our other cat had a cancer scare; both of our cats required major surgery; and one of my wife’s best friends lost her sister-in-law, her niece, and all three of her very young children in a catastrophic car accident that left three other people dead as well.

So it’s entirely possible that as effective and affecting as I find Mark Gruenwald’s magnum opus, my real life is doing a lot of the heavy lifting. Certainly there are a couple of very different ways to read this, arguably the first revisionist superhero comic available to the North American mainstream. For some people, no matter how interesting Gruenwald’s ideas are in terms of laying out the effects of a Justice League of America-type group’s decision to really make the world a better place by transforming society into a superhero-administered utopia, the execution–art, dialogue, and melodramatic plotting all firmly in the mainstream-superhero house style–cuts it off at the knees. For others, it’s precisely that contrast between the traditional stylistics of the superhero and a methodical chronicling of superheroes’ disastrous moral and physical shortcomings that makes the book work.

Count me in the latter category. Squadron Supreme may have more in common with later pseudo-revisionist works like Kingdom Come than it does with Watchmen in that it obviously stems from a place of great affection for the genre rather than dissatisfaction with it. Heck, even The Dark Knight Returns, which is really a celebration of the superheroic ideal, earns its revisionist rep for a thorough dismantling of the superheroes-as-usual style, something Squadron Supreme couldn’t care less about. No, by all accounts (certainly by the testimonials from Mark Waid, Alex Ross, Kurt Busiek, Mike Carlin, Tom DeFalco, Ralph Macchio, and Catherine Gruenwald printed as supplemental materials here) Mark Gruenwald seems to be working in Squadron as a person who loves superheroes so much that he can’t help but try to find out just how far he can take them. That what he comes up with is so bleak and ugly–nearly half of his main characters end up dead, for pete’s sake–is fascinating and sad. It’s like watching Jack Webb do another season of Dragnet consisting of plotlines from The Wire Season Four: Against America’s broken inner-city school system and grinding cycle of poverty, violence, corruption, and abuse, even Sgt. Joe Friday would be powerless.

Of course, in Squadron Supreme the heroes generally do prove able to conquer humankind’s intractable problems. A combination of the kind of supergenius technology that under normal circumstances only gets used to create battle armor or gateways to Dimension X and the tremendous sheer physical power of the big-gun characters proves enough to end war, crime, and poverty, and even put a hold on death. (The book’s vision of giant “Hibernaculums” in which thousands of frozen corpses are interred until such time as medical science discovers a cure for their condition is one of the book’s great, haunting moments of disconnect between cheerful presentation and radical society-transforming idea.) Gruenwald and his collaborators seem to have no doubt that should Superman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, the Flash, and the rest of the JLA (through their obvious Squadron analogues) be given the reins of the world, they really could solve all our problems for us.

It’s the methods they’d use to get us there that Gruenwald has doubts about. A Clockwork Orange-style brainwashing for criminals; a Second Amendment-busting program of total disarmament for military, law enforcement, and civlians alike; a takeover of many of the key functions of America’s democratically elected government–despite placing his beloved heroes at the center of these plots, it’s no secret where Gruenwald’s sympathy lies. (To return to the Hibernaculums again, a brief sequence involving “right to die” protestors features some of the book’s most provocative ideas just painted on their placards, eg. “WITHOUT DEATH, LIFE IS MEANINGLESS!!!” Yes, there were three exclamation points on the sign.) Still, Gruenwald backpedals from condemning his heroes for their excesses outright: During the book’s climactic confrontation, as bobo Batman Nighthawk wages a war of words with Superman stand-in Hyperion, the rebel leader reveals his biggest problem with the Squadron’s “Utopia Program” to be his fears over what will happen to it when the golden-hearted Squadron members are gone and someone less worthy takes over their apparatus of complete control. (It’s worth noting that the Squadron gets the idea for the Utopia Project as a solution for the damage they themselves did to the planet while under mind control by an alien tyrant.)

But parallel to the big political-philosophical “What If?” ramifications runs another, more affecting revisionist track. This one focuses on the individual problems and perils of the Squadron members. Some of these flow from the underlying Utopia Project scenario, and about those more in a minute, but other times–a Hyperion clone succesfully impersonating him and seducing the Wonder Woman character, Power Princess, in his place; little-person supergenius Tom Thumb (just barely an Atom analog) dying of cancer he’s not smart enough to cure–Gruenwald simply takes a familiar superhero trope or power set and plays the line out as far as it’ll go. In some cases, such as setting up a fundamental Batman/Superman conflict, making Superman and Wonder Woman an item, explicitly depicting the Aquaman character Amphibian as an odd man out, and dancing up to the edge of Larry Niven’s “Man of Steel, Woman of Kleenex” essay on the dangers of superhero sex, I would guess Gruenwald was for the first time giving in-continuity voice to the stuff of fanboy bull sessions that had taken place in dorm rooms and convention bars for years.

While that’s a lot of fun, it’s the unique touches brought to the material by Gruenwald, shaped into disconcerting images by his rotating cast of collaborators (mostly Bob Hall and Paul Ryan), that get under your skin. Nuke discharging so much power inside Doctor Spectrum’s force bubble that he suffocates himself. The vocally-powered Lady Lark breaking up with her boyfriend the Golden Archer under a suppressive cloud of giant, verbiage-filled word balloons. A comatose character’s extradimentional goop leaking out of him because his brain isn’t active enough to stop it, threatening to consume the entire world until Hyperion literally pulls the plug on his life support system. Power Princess tending to her septuagenarian husband, who she met when she first made the scene in World War II. Hyperion detonating an atomic-vision explosion in his semi-evil doppelganger’s face, then beating him to death. Tom Thumb’s death announced in a panel consisting of nothing but block text, unlike anything else in the series. Amid the blocky, Buscema-indebted pantomime figurework and declamatory dialogue, these moments stand out, strangely rancid and difficult to shake.

Perhaps no other aspect of the book gives Gruenwald more to work with than the behavior modification machine. There are all the ethical debates you’d expect–free will, the forfeiture of rights, the greater good. There’s the slippery slope of mindwiping you saw superheroes slide down decades later, and far less interestingly, in Identity Crisis. But again, the personal trumps the political. The standout among the series’ early, episodic issues is the one in which Green Arrow knockoff the Golden Archer (who has the second-funniest name in the series, after Flash figure the Whizzer) uses the b-mod machine on Black Canary stand-in Lady Lark to make her love him after she rebuffs his marriage proposal. She ends up unable to bear being away from him, her fawning driving him mad with guilt, and even after he comes clean about his deception and is expelled from the team, the modification prevents her from not loving him. Later, the device’s use on some of the Squadron’s supervillain enemies turns them into obsequious allies-cum-servants whose inability to question the Squadron, and moreover to feel anything but thrilled about this, does more to turn your sympathies against the SS than all the gun-confiscation scenes in the world.

Late in the book, another pair of behavior modification-related incidents ups the pathos to genuinely disturbing levels. When b-modded ex-villain Ape X spies a new Squadron recruit secretly betraying the team, her technologically mandated inability to betray the Squadron member by telling on her or betray the rest of the team by not telling on her overwhelms Ape X’s modified brain and turns her into a vegetable. And when Nighthawk’s rebel forces kidnap the mentally retarded ex-villain the Shape in order to undo his programming, his childlike pleas for mercy are absolutely heartbreaking, as is the cruel way in which the rebels repeatedly deceive him in order to advance their aims. The look of panic on his face as he shouts “Don’t hurt Shape please!” is tough to stomach.

What it reminds me of more than anything is taking an adorable stuffed animal that you love and throwing it in the garbage. Do you know that feeling? This is not a sentient creature, it does not and cannot interact with you in any real way–and yet you love it. It never did anything to hurt you. Why would you want to throw the poor guy away? No, don’t! By the time you get to the end of Squadron Supreme, a love-letter to the Justice League of America that ends with an issue-long fight that leaves half the participants brutally slaughtered, that’s the feeling I get from the whole book. These superheroes never did anything but bring Mark Gruenwald great joy, he wanted to repay that by doing something unprecedented with them, but as it turns out the unprecedented thing to do was to throw them away.

Comics Time: Spotting Deer and SM

February 4, 2011Spotting Deer

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

Koyama Press, December 2010

12 pages

$5

Buy it from Michael DeForge

SM

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

self-published, December 2010

12 pages

I forget what it cost

“Although physically similar to a common white-tailed deer (Ocoileus virginianus), the spotting deer (Capreolus vulgaris) is actually a kind of terrestrial slug.” So begins the first of two short, creepy comics debuted by Canadian wunderkind Michael DeForge at this past December’s Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival, and so does one get a sense of the type of skin-crawly, dis-ease driven horror DeForge is creating here. In the guise of a nature guide, the cartoonist not only piles discomfiting detail (“Its ‘antlers’ are actually colonies of parasitic polyps that are first attached to the deer during adolescence”) upon discomfiting detail (“biologists nickname this phenomenon the ‘sexual acqueduct'”), but trots out a unique and fully formed full-color palette to do so; he then whisks the comic into unexpected territory by making it just as much about the obsessive in-story writer of the guide, whose face we never see even as evidence quietly accrues that his interest in these strange creatures has more or less ruined his life. The self-published SM is similarly based in the horror of the squicky and gross (a snowman stands mutely smiling as two teenagers take a knife to it, unpleasantly revealing that it’s somehow made out of real flesh) and similarly takes off into unpredictable territory (the flesh is hallucinogenic; the snowman’s nearest neighbor is a Texas Chain Saw Massacre-style old man who doesn’t take kindly to trespassers). As if compensating for the comparative lack of color, DeForge makes the book’s centerpiece as sensual as possible: It’s a full-on psychedelic freak-out laid atop a topless makeout session by an ersatz Maggie and Hopey. It’s enough eye candy to send you into the visual equivalent of diabetic shock, which somehow leaves you even better prepared to picture the unpleasantness that goes on between panels on the subsequent page and is about to go on after that elegant final panel. The best part of all, of course, is that while DeForge’s alt-horror idiom is familiar enough (especially to me, especially lately), his personal drawing style isn’t; DeForge’s comics really do look only like themselves. Give me more.

Comics Time: Studygroup12 #4

February 2, 2011Studygroup 12 #4

Zack Soto, Steve Weissman, Eleanor Davis, Michael DeForge, Trevor Alixopulos, T. Edward Bak, Chris Cilla, Max Clotfelter, Farel Dalrymple, Vanessa Davis, Theo Ellsworth, Jason Fischer, Nick Gazin, Richard Han, Jevon Jihanian, Aidan Koch, Amy Kuttab, Blaise Larmee, Corey Lewis, Kiyoshi Nakazawa, Tom Neely, Jennifer Parks, Karn Piana, Jim Rugg, Tim Root, Ian Sundahl, Angie Wang, Dan Zettwoch, writers/artists

Zack Soto, editor

Milo George, editorial/technical advisor

Published by Jason Leivian and Zack Soto, December 2010

80 pages

$20

Buy it from Zack Soto

This is going to come out sounding waaaay more like a diss than it’s intended to, but in flipping through the comeback installment of this Zack Soto-edited alt/artcomix anthology a few weeks after my initial read-through, I realized I didn’t remember anything in it prior to cracking the covers once again. Which is fine, I think! Looking at it now, Studygroup12 #4 seems to me to be much more an art book than a comics anthology. For one thing it’s exquisitely made: Beautiful screenprinted neon-pink-and-aqua covers inside covers (trust me, it’s much glowier than the scan above suggests); a gallery of impactful pink/blue/purple splash pages to kick things off and close things out, including some of the most striking images Jon Vermilyea and Dan Zettwoch have ever constructed out of their customary melty-monster and diagram styles respectively; pages printed in the vivid, inky blue-purple of a carbon copy. It’s a lovely package even compared to the similar approaches of Mould Map and Monster. My point is simply that all these things point to a book that works better from moment to moment as a catalog of images and illustrations rather than one whose strength arises from the cumulative impact of individual sequential narratives. Flipping through, I’m struck by the weird mystical sensuality of Aidan Koch’s portraiture and triangular caption boxes; the Renee-French-on-a-photocopier haze of Jennifer Parks’s creepy little strip; the pleasure of seeing Tom Neely images reproduced at a much larger size than his customary minicomics; the strength of the way Vanessa Davis designs leering faces, something that’s much clearer to me here than its ever been in the comics I’ve seen from her elsewhere, which frankly have never bowled me over the way they have so many readers; some funny punk/thrash/metal/trash pastiches from Vice Magazine’s mustache-at-large Nick Gazin (I wish a HAUNTED HOLOCAUST: “THE TEENAGE TITS TOUR” t-shirt actually existed). But much of what really reads as comics does so rather weakly — an uncharacteristic experimental misfire from Michael DeForge; the return of USApe, my least favorite Jim Rugg character; diminishing returns from Vermilyea’s anthropomorphized breakfast gang, which here get a little too Milk and Cheese-y; a Farel Dalrymple strip that’s drowned out by its over-shading; etc. Ultimately it’s really only Blaise Larmee’s riotously confrontational anxiety-of-influence comic, in which one of his trademark prepubescent/elfin protagonists navigates her way through some sort of abstract geometric maze only to stand in front of a menacing reproduced photograph of Charles Schulz (!!!), that hits me hard as comics; perhaps not coincidentally it’s the first time I’ve seen anything from his whole Comets Comets crew that makes good on their kill-yr-idols gotta-make-way-for-the-homo-superior internet trolling. As a look at the Portland-helmed turn-of-the-decade artcomix look, it’s swell; as a look at their comics, and where they might take everyone else’s, it’s only a start.

Comics Time: Snake Oil #6: The Ground Is Soft

January 31, 2011Snake Oil #6: The Ground Is Soft

Chuck Forsman, writer/artist

self-published, December 2010

56 pages

$7

Buy it from the Oily Boutique

Last time we checked in with Chuck Forsman, he was chronicling a young man trapped in an unrewarding life by the demands of family and culture and his own inability to muster the gumption to really try to escape them. Here, he…chronicles a young man trapped in an unrewarding life by the demands of family and culture and his own inability to muster the gumption to really try to escape them. But you’d be surprised, stunned even, to see how far away from Snake Oil #5’s straightforward slice-of-lifer Forsman can get even within that basic tonal template. In The Ground Is Soft, Forsman employs a sort of late-model Dan Clowes kaleidoscopic-narrative effect to tell a vaguely alt-fantasy story about an abusive warrior-father, his hapless would-be-priest son, his two wives (one loving, the other a little too loving), and the customs that govern their society and their lives, which are largely inscrutable until the kaleidoscope is shifted in just the right way toward the end of the book, revealing something deeply unpleasant about the culture and (potentially) redeeming about the father, depending on how you look at it. It’s very smart work, with a sense of humor that’s more somber than traditionally black, and a degree of control over how the one- or two-page vignettes assembled out of chronological order to tell the tale play off one another and hold back the big reveal until the very last minute. As was the case with his contribution to Monster I’m really not sure why he chose to cap things off with the equivalent of the sort of corny joke accompanied by a wah-wah trombone sound — go ahead, be bleak, nobody minds, man! I certainly don’t. This guy’s good.

Comics Time: Uptight #4

January 28, 2011Uptight #4

Jordan Crane, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, December 2010

36 pages

$3.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

It’s the details that distinguish what Jordan Crane does. He’s not breaking any conceptual or thematic or formal ground in the two stories comprising this fourth issue of his old-school solo-anthology alternative-comic-book series, both of which are continuations of previous stories: “Trash Night” picks up the misadventures of a working-class couple whose female half is conducting a secret affair, while “Dark Day” is another chapter in the saga of Simon and Jack, the school-hating kid and his giant cat who starred in Crane’s all-ages graphic novel The Clouds Above. The latter story is part of your basic “kid explores a magical world beyond the watchful eyes of adults” set-up, while the former presents love and sex through a sordid, hate-fucky lens, an approach I’ll always associate with the 1990s filmography of Jeremy Irons. But none of that accounts for the sticky, unexpected images he pours into these familiar templates. For “Trash Night,” that means the perversely sensual lifelessness of the wife’s eyes, mouth, and breasts as the husband cradles her dead body in a mordant daydream (a recurring theme for Crane at this point); the memorable specificity of the argument that sends her back into the arms of her lover (vegetable oil!); the out-of-nowhere suddenness and savagery with which he attempts to strip her naked when she returns home; the shadowy, samurai-esque way he holds aloft a rake before bringing it down on the body of a raccoon who bit him; the unexpected and believably unglamorous way their bout of make-up sex begins (with him sitting on the toilet as she puts neosporin on his wound); and even the multiple meanings of the title itself, which could refer not just to the husband’s chores but to his likely self-identification as white trash and to the quality of his experiences during the time period. “Dark Day” is equally cleverly named in that it quietly ties this much frothier all-ages affair to the grim day-in-the-life we just read about, and uses irony to draw our attention to how much lighter this strictly black-and-white strip feels compared to the dingy, depressive graytones of the earlier comic. Here, Crane uses his wispy line as a way to cram visual cacophony into each panel, conveying how seeing an adult-created and administered world in disarray can be frightening to a child — the principal’s office, all books and papers and plaques and diplomas precariously overhanging the principal’s ogre-like frame, is at least as menacing as the shadows and icicles and smoke that Simon and Jack and Rosalyn must navigate and escape. At this stage in his career it’s quite clear how impeccable Crane’s technique is, both as an artist and as a designer; I think it’s equally important to note that what he does with that technique is just as considered and just as well-executed.

Comics Time: AX: Alternative Manga Vol. 1

January 26, 2011 AX: Alternative Manga Vol. 1

AX: Alternative Manga Vol. 1

Osamu Kanno, Yoshihiro Tatsumi, Imiri Sakabashira, Takao Kawasaki, Ayuko Akiyama, Shigehiro Okada, Katsuo Kawai, Nishioka Brosis, Takato Yamamoto, Toranosuke Shimada, Yuka Goto, Mimiyo Tomozawa, Takashi Nemoto, Yusaku Hankuma, Namie Fujieda, Mitsuhiko Yoshida, Kotobuki Shirigari, Shinbo Minami, Shinya Komatsu, Einosuke, Yuichi Kiriyama, Saito Yunosuke, Akino Kondo, Tomohiro Koizumi, Shin’ichi Abe, Seiko Erisawa, Shigeyuki Fukumitsu, Kataoka Toyo, Hideyasu Moto, Keizo Miyanishi, Hiroji Tani, Otoya Mitsuhashi, Kazuichi Hanawa, writers/artists

Sean Michael Wilson, editor

Mitsuhiro Asakawa, compiler

Top Shelf, 2010

400 pages

$29.95

Buy it from Top Shelf

Buy it from Amazon.com

This is a tough one. I mean, as a Whitman’s Sampler of approaches to Japanese comics outside of the Japanese mainstream, this inaugural English-language compilation of comics from the fat, regularly released alternative-manga anthology series AX strikes me as wide-ranging and comprehensive, almost to a fault. In terms of known quantities for American altcomix readers, you’ll find both the straightforwardly drawn irony of gekiga pioneer and a A Drifting Life author Yoshihiro Tatsumi and the over-the-top visual and thematic crudeness of Monster Men Bureiko Lullaby‘s Takashi Nemoto represented here. You’ll see comics that look very much like the lavishly illustrated horror or porn manga you might have come across (Takato Yamamoto, Keizi Miyanishi, Kazuichi Hanawa) and comics that are so far removed from the manga tradition and so similar in bold graphic spirit to the first wave of North American alternative comics that they’d fit in RAW (Nishioka Brosis, Otoya Mitsuhashi). In perhaps the most marked deviation from work from the equivalent time period (turn of the millennium) here in North America, there’s a metric ton of crass taboo-shattering of the sort cartoonists here haven’t been all that interested in as an end in itself since the underground days (Tatsumi, Nemoto, Mitsuhashi, Osamu Kanno, Shigehiro Okada, Kotobuki Shiriagari, Saito Yunasuke, Hiroji Tani), but there are also twee little slice-of-lifers, modern urban fables, and O. Henry/New Yorker litfic that you could easily see populating a Petit Livre from Drawn & Quarterly or an issue of Mome (Takao Kawasaki, Katsuo Kawai, Shinbo Minami, Akino Kando, Shin’ichi Abe, Shigeyuki Fukumitsu).

So your preferred color of the alt/art/lit/indie/indy/underground spectrum is almost surely represented somewhere in these pages, and chances are you’ll find something you’ll consider a minor revelation. In my case, I was really impressed by the murky, inky body-horror dream comic “Conch in the Sky” by Imiri Sakabashira, the title of which gives a pretty solid impression of what you can expect. Brosis’s “A Broken Soul” combined off-kilter 2-D character designs, a wiry thin line, gray textures that looked like an artifact of photcopying, and a sort of whimsical ennui, to remind me favorably of Mark Beyer. And Shinya Komatsu’s “Mushroom Garden” is a real stunner, its bulbous, plush mushrooms evoking an array of psychedelic comics practitioners from Vaughn Bode to Moebius to Brandon Graham. In other words I don’t regret the time spent with the volume at all, and it’s given me several promising roads for further exploration, god and translators willing.

That said, AX Vol. 1 is consistently undercut not just by the heavy hand of many of its contributors, too many of whom rely on shock value or Tatsumiesque hamfisted irony, but by various production shortfalls. First and foremost among those is the translation work by Spencer Fanctutt and Atsuko Saisho, which is the epitome of the translated-manga tendency to emphasize fidelity at the expense of clarity. Here’s a representative passage from Shigehiro Okada’s sex farce “Me”: “However strangely I might dress, if I could really slip my existence, I could become a part of the cityscape like those ruins of decades ago. My instinct would explode if it took form. The light holds death. The darkness holds life. That’s what I’m waiting for. I…I would die for its expression.” If it’s not a sentence you can imagine a native English speaker coming up with, you’ve got to go back to the drawing board!

Meanwhile, while the design and font selection for the jacket, table of contents, and ancillary material (including Paul Gravett’s informative, if slightly overwritten, introduction) are all quite strong, the lettering for the comics themselves is frequently distracting, with inexpressive computer fonts and, often, vast empty spaces in balloons and caption boxes where kanji clearly used to reside. Finally, the decision to list creators first-name-first in the TOC and on each page but last-name-first in the who’s-who at the back of the book is a baffling one.

None of these things are dealbreakers in and of themselves. Heck, I don’t think they’re dealbreakers even when all added up. Like I said, there are a lot of intriguing comics in here, and a few excellent ones, and the cumulative effect is an eye-opening and educational one if you’re a reader with an interest in Japan’s equivalents to the American alternative comics you enjoy but few inroads into them. But in a field that’s increasingly crowded with impeccably conceived, assembled, edited, and packaged anthologies, AX isn’t just competing with scanlators and sporadic English-language apperances in long out-of-print publications, it’s competing with what the Eric Reynoldes and Zack Sotos and Sammy Harkhams and Ivan Brunettis and Ryan Sandses and so-ons of the world are putting together. It’s in that sense that AX could stand to be sharpened. (Sorry, couldn’t resist.)

Comics Time: Johnny 23

January 24, 2011Johnny 23

Charles Burns, writer/artist

Le Dernier Cri, December 2010

64 pages

$24.95 price

Buy it from Le Dernier Cri

Buy it from PictureBox

X’d Out: This Is The Remix. For reasons unknown and with results most welcome, Charles Burns decided to cut up, shrink down, re-order, and re-release his recent surrealist art-sex satire/Tintin tribute, substituting English for an invented alien alphabet and language (has anyone translated it yet?) and reconfiguring the story into something recognizable but still very different. The trick here is that Burns realizes that the recurring images that populate X’d Out — photographs, holes, voyeurs, fetuses, eggs, wounds, cats, vents, nudes — can be used not only as dreamlike leitmotifs but as Legos, basically — connective nubs that allow him to disassemble the original narrative and put it back together in a new way, with the material between those recurring images treated like interchangeable bricks. Couple this with the inscrutable lettering and dialogue and the effect is even more dreamlike, and even more overpowering. The book’s protagonist Johnny 23/Nitnit is tossed seemingly willy nilly from one reality to another; he’ll walk through a hole in the wall in one world as one version of himself and exit into another as the other; he’ll look through a window and see himself; he’ll pick up a photo, we’ll look at the photo, and then we’ll see that his alter ego is now holding it. The book’s new landscape format furthers the sense of relentless forward momentum now that the pages are longer than they are tall, and the luscious purple ink in which the now colorless line art is printed emphasizes the sensuality of the images even more powerfully. It’s some weird erotic nightmare constructed from raw formal mastery of comics. What a performance.

Comics Time: Monster

January 21, 2011 Monster

Monster

Paul Lyons, Jim Drain, Michael DeForge, Michaela Zacchilli, Brian Ralph, Chuck Forsman, James Kochalka, Jim Rugg, Peter Edwards, Andy Estep, Oscar Estep, CF, Brian Chippendale, Blade, Keith McCulloch, Mike Taylor, Roby Newton, Edie Fake, Leif Goldberg, Keith Jones, Dennis Franklin, Jo Dery, Erik Talley, Beatrice McGeoch, Tony Astone, Mat Brinkman, Nick Thorburn, Melissa Mendes, Aaron DeMuth, writers/artists

Paul Lyons, editor

self-published (I think), October 2010

88 pages

$20

Buy it from PictureBox

They’re gettin’ the band back together, man! From out of the rubble of Fort Thunder rises the surprise 2010 revival of the gigantically influential Providence underground-art institution’s house anthology, featuring mostly-about-monsters work from all six of the Fort’s core cartoonists — Brinkman, Chippendale, Ralph, Drain, Lyons, Goldberg. Plus Andy Estep, Peter Edwards, Roby Newton, and a lot of other people you’ll see listed as having lived/worked/played in the Fort. Plus fellow-travelers like Providence’s CF and Jo Derry and Highwater’s James Kochalka. Plus Jim Rugg and Michael DeForge and Chuck Forsman and other leading lights of post-Fort alternative comics. And a reunion tour is exactly what it feels like.

Don’t get me wrong, there’s fine comics in this beautifully printed navy-blue-and-white package, many of which take advantage of its unusually large trim size. (We’re not talking Kramers Ergot 7 territory, but the thing is big. Think the Wednesday Comics hardcover.) Brian Ralph uses his comparatively clean cartoony style for a hilariously violent giant-robot comic, “Voltron from Hell,” basically, with huge panels and splash pages taking perversely pretty delight in mass destruction and death. The final panel of CF’s weird tale about an ambulance driver-cum-cat burglar who sneaks into the house of a woman with a mysterious disease actually made me jump — just a beautifully done little scare. Brian Chippendale’s story ties in with his Puke Force webcomic and gives him a chance to draw some villains at full splash-page size. I thought Chuck Forsman cut himself off at the knees a bit with his punchline ending, but until then his contribution was a creepy little thing that reminded me favorably of the urban legend my Delawarean wife recounted to me about the zoobies, the inbred mutant children of the DuPont family who would roam around the woods waylaying passers-by. There are insanely METAL full-page illustrations from Brinkman (who’s by now made a wonderful career of such things), Tony Astone, and Dennis Franklin — I mean, I laughed out loud at how fuckin’ devil-horns they were. And Lyons’s wraparound cover portraits of various barfing beasts is breathtaking, one of the most impressive single comics images of the year.

But in a way, the Fort Thunder aesthetic is a victim of its own success. I lost track of the number of good-to-great comics that came out this year bearing its influence, and those apples-to-apples comparisons make it hard for the work here, which I think all parties involved would admit was done more for fun than for tear-down-the-walls boundary-pushing, to stand out. In terms of anthologies alone, you could stand this one right between Studygroup 12, Closed Caption Comics, Smoke Signals, Diamond Comics, and Mould Map. Fort Thunder and the Providence scene’s DNA is now deeply embedded in an array publishers, including not just the late and lamented Highwater, Bodega, and Buenaventura, but also PictureBox, Secret Acres, Koyama, Nobrow, Pigeon, Gaze, and even the mighty Drawn & Quarterly. Moreover, whether you call it fusion or New Action or simply slap an alt- prefix in front of horror or SF or fantasy, Fort Thunder’s pioneering jailbreak of genre from the mainstream American comics prison has subsequently allowed it to become almost inescapable in smart-comics circles. Finally, Chippendale, Brinkman, Forsman, DeForge, CF, Fake, and Rugg are all in direct competition with work they put out elsewhere last year, most of which was more ambitious. And understandably so! Seriously, I’m not complaining — Monster is what I think it set out to be. It’s seeing Floyd get together for an awesome Live 8 gig, rather than seeing Waters and Gilmour working together again, and as such it’s more a treat for the fans than documentary evidence of why we became fans in the first place.

Comics Time: FUC* **U, *SS**LE

January 19, 2011 FUC* **U, *SS**LE

FUC* **U, *SS**LE

Johnny Ryan, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2010

pages

$11.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

Take a good look at that cover, if you will, and you’ll see what it is that makes Johnny Ryan’s grossout humor comics so special. Blecky Yuckerella isn’t just emitting bog-standard gag-strip flopsweat and stinkflies as she hangs, she’s also squirting out tiny little drops of urine. That’s the kind of attention to detail and willingness to go the extra mile that took Ryan to the top!

In Ryan’s last Blecky collection (co-Bleck-tion?), the fun came in seeing the pacing economy of the four-panel gag strip used as a vehicle for a completely unconstrained sense of the absurd, a willingness to turn the corner into even weirder and more ridiculous or offensive territory with each new panel. By contrast, the fun of FUC* **U, *SS**LE (aside from the title itself, Ryan’s best since Johnny Ryan’s XXX Scumbag Party) is mostly how straightforward it is: Ryan’s got a punchline in mind, and by god he’ll set it up in those first three panels no matter how idiotic it is. Wine made from stomping pig carcasses (“I call it S’wine!”), Curly Moe and Larry as the Messiah (“It’s Stoogeus Christ!”), diarrhea caused by eating Bigfoot (“the Sasquirtz”), a porno called 69-11 (“It’s like 9-11, only more erotic!” Blecky points out as Flight 11 and the North Tower perform oral sex on one another) — I’d say “you can’t make this shit up,” but you can, or Ryan can at least, and watching him frogmarch his characters through the outlandish scenarios needed to give birth to these you-gotta-be-fucking-kidding-me ideas is Guffaw City. And as I always point out, he’s a fine, fine cartoonist; this idea has more traction in a post-Prison Pit world, I know, but you don’t get to see his buoyant brushwork in those books, while here it’s what sells the childlike glee of everything that’s going on. His thick blacks really vary up the dynamics of each page, too. Unfortunately, this Blecky’s final hurrah, as Ryan has retired the strip. You can certainly see how Prison Pit and Angry Youth Comix afford him a lot more formal leeway, but I’m going to miss the consistently high batting average on display in the Blecky books. I guess it’s like Blecky herself tells Aunt Jiggles: “You can either have a lotta annoying noise and a clean robot pussy, or peace and quiet and nasty robot pussy stench. But you can’t have it both ways!”

Comics Time: A Drunken Dream and Other Stories

January 17, 2011 A Drunken Dream and Other Stories

A Drunken Dream and Other Stories

Moto Hagio, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2010

288 pages

$24.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

I frequently gasped, out loud, at the beauty of this goddamn thing. Pioneering Japanese girls’-comics artist Moto Hagio is not a world a way from the shoujo artists you might have seen elsewhere; theirs is a shared vocabulary of thin, beautiful women and men who look like their emotions could lift them off the ground. But Hagio’s line is just a little bit fuller, her character designs a little more lived-in, the endings of her stories a less likely either to pull punches or hit you full-force with maudlin tragedy. Most of them remind me of Jaime Hernandez, of all people, in that the force of the narrative is toward the protagonists coming to terms — with the damage done by a cruel mother, with the inspiration that arose unexpectedly from a childhood tragedy, with the sudden loss of a friendship through a shared mistake in judgment, with the death of a hated rival, with a necessary but traumatic decision, with the death of a parent. Or not! Some characters die, some characters are never afforded the rapprochement they seek, and one little girl gets zapped into nothingness by the conformist overlords of her suddenly science-fictional home. Either way it’s the visual journey that counts just as much as the destination, a journey in love with lush gray textures and stippled explosions of light, and in one memorable strip an array of red-based colors from horror-movie-blood red to rusty russet to hot pink, and portrayed through luxurious swooping lines that make the characters they depict look like Precious Moments dolls gone sexy. (A good thing, I promise you!) Each story’s big narrative and emotional moments seem to swell within and explode out of these textures and lines, like they’ve actualized the potential energy there all along. I dunno, I’m probably sounding a little ridiculous — my point is simply that this is the kind of book whose impact comes as much from simply soaking in the images as reading them, like great comics ranging from Kirby to Fort Thunder. Editor Matt Thorn, who also provides a lengthy essay on and interview with Hagio, is also the book’s translator, and he does a magnificent job; I can’t tell you what a relief it is to read manga with none of the clumsy, overly literal sentence constructions that frequently plague even the best and most well-intentioned such projects, ironically thwarting the author’s intended effect in the name of fealty. Really, really fantastic lettering, even — how often can you say that about translated manga? Reads like a dream, looks like a dream.

Comics Time: Map of My Heart

January 14, 2011Map of My Heart

John Porcellino, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, October 2009

304 pages

$24.95

Buy it from Drawn & Quarterly

Buy it from Amazon.com

I’ll be honest: I skipped most of the prose stuff. I’ve never felt much kinship with zine culture, and among all the other things that John Porcellino’s legendary, long-running, self-published minicomic series King-Cat Comics and Stories is — most notably a pioneering combination of pointilist autobiography and minimalist cartooning without which the careers of Kevin Huizenga, Jeffrey Brown, James Kochalka, James McShane, and virtually every webcomic diarist would be unthinkable — it is also a zine. Over the years it’s functioned, essentially, as one end of a pen-pal conversation between Porcellino and his readers, and thus his lengthy handwritten digressions about fishing trips or local wildlife or his Top 40 lists of stuff he’s recently enjoyed serve a necessary and fruitful role during that particular round of correspondence. But that’s never how it’s functioned for me: My experience reading Porcellino and King-Cat has come either from buying a bunch of issues all at once and reading them in one go or from seeing his work in collections like this one. I’m here for the cartooning, not for the conversation.

Fortunately the cartooning is fantastic. The stretch of “comics and stories” collected here run from 1996-2002, a pivotal time period for Porcellino not simply in personal terms — he became critically ill, recovered, moved back home to Illinois after years spent in Denver, married, divorced, and remarried — but in artistic ones as well: I’m reasonably sure his long-form memoir Perfect Example was constructed during this time, and within King-Cat his art made its second quantum leap. After what looks to my admittedly inexpert eyes like an experiment with a brush in issue #57 (which followed and revealed his divorce), his line becomes a true thing of beauty in issue #58’s story “Forgiveness.” It’s smoother and thinner, its curves more graceful, the sense of space between them less cluttered and more balanced. With no captions to guide us, we’re left alone with young John in this reminiscence of an unintentional act of cruelty that clearly still haunts him; the image of his younger self twice curled into a fetal position, repeating “I’m sorry” over and over again, is devastating. Similar flashes of remonstrance and self-loathing creep up occasionally and unexpectedly in some of his Zen-influenced comic poems, a powerful juxtaposition with their serene images and contemplative words. Can it get a little twee? Sure, but I think there’s a sharpness and a coldness to that line, and the occasional glimpses of despair it affords us, that make writing Porcellino’s stuff off as cutesy hippie stuff a big mistake. To flip through the comics material in Map of My Heart is to get a picture of a man fighting to find beauty in the world even as what he’s seen of it buffets him around like one of the leaves on the breeze that he draws. No wonder people loved to hear from him.

Comics Time: Bodyworld

January 12, 2011Bodyworld

Dash Shaw, writer/artist

Pantheon, April 2010

384 pages, hardcover

$27.95

Read it for free at DashShaw.com

Buy it from Amazon.com

Did everyone know this was a comedy but me? I actually put off reading Dash Shaw’s, what is it now, second magnum opus and first full-length science-fiction graphic novel because I find the formal experimentation of his SF stuff intimidatingly difficult to parse even in short-story format — surely a 400-page webcomic turned fat hardcover would fuck my shit up, right? But while Shaw’s shorts frequently swap complexity for clarity, at least for me, Bodyworld is a breeze to read. Part of that’s physical — the fun of its vertical layout, kicking back and flipping the pages upward on your lap or desk. But mostly it’s that the thing reads like a quirky indie-movie genre-comedy — think a mid-00s Charlie Kaufman joint, or Duncan Jones’s Moon with more laffs ‘n’ sex. We follow one helluva protagonist, Professor Paulie Panther, a cigarette-smoking, plain white tee-clad schmuck who wouldn’t look out of place hanging out with Ray D. and Doyle in a Jaime Hernandez comic and who has harnessed his prodigious appetite for doing drugs and not doing work into a career as a field-tester for hallucinogenic plants. Basically, he travels around the world smoking anything that looks unusual. For the purposes of Bodyworld that has taken him to Boney Borough, a Thoreau-like enclave whose planners mixed unfettered nature right into the zoning laws as a response to a horrific decades-long Second Civil War that began ravaging the United States, it seems, following the installation of George W. Bush. There he discovers a smokable plant that gives its users a telepathic bond with anyone in their proximity, leading to disastrous romantic entanglements and disentanglements with the local high school’s hot teacher, its prom king, and his girlfriend. But there’s more to the plant that meets the eye, and a Repo Man-style series of surreal/slapstick/science-fictional escalations leads to a funny but still black and potentially apocalyptic ending, like the Broadway version of Little Shop of Horrors.

Bodyworld‘s webcomic incarnation was famous for its vertical scroll, and for my money it’s recreated enjoyably by the vertical flip in the book format. What surprised me about Shaw’s other formal innovations here is how relatively restrained they are. You don’t really need to keep track of his complex, color-coded grid maps of Boney Borough or the school to understand what’s going on where, and the to the extent that he plays with overlaps and repetition and color and so on it’s mostly done to convey the hallucinogenic mind-melding engendered by the drug, quite effectively, at that. Moreover, I’ve often found his character designs hard to parse and hard to like — something about the way they’re constructed from purposely ugly swirls and swoops just gives me prosopagnosia — but his quartet of leads and dozen or so prominent supporting characters are by far his strongest ever in this area; you really can get who they are and what they’re about just by looking at them, which prospect is not at all unpleasant, either. And while some of the yuks fall flat (particularly with the town sheriff late in the game), it’s for the most part a dryly witty, occasionally laugh-out-loud funny comedy, with finely observed humor about high schoolers, teachers, druggies, hoary sci-fi tropes, and the sort of shiftless ne’er-do-wells you enjoy spending an evening with when your buddy brings them along. In short, it’s a prodigiously ambitious cartoonist plying the various tricks of his trade just to tell a good story you can catch some weekend afternoon and then chat about with friends at the diner afterwards.

Comics Time: Mould Map #1

January 10, 2011Mould Map #1

Jason Traeger, Daniel Brereton, Aidan Koch, Massimiliano Bomba, Stéphane Prigent, Kitty Clark, Matthew Lock, Lando, CF, Jonathan Chandler, Matthew Thurber, Brenna Murphy, Drew Beckmeyer, Colin Henderson, Leon Salder, writers/artists

Hugh Frost, Leon Sadler, editors

Landfill Editions, December 2010

16 large pages

$12

Buy it from Landfill

Buy it from PictureBox

Learn more at MouldMap.com

Ingenious idea, meet ingenious execution. In this gorgeously printed, oversized anthology, a posse of prominent and obscure artcomickers create evocative one-page science-fiction strips/images/whatever — not so much to tell a complete story as to convey a mood, an environment, a series of story possibilities that emerge into the past and future of the events depicted on the page. Aidan Koch’s bold all-caps lettering meshes perfectly with her story of a nude, distraught wanderer of the highways who knows that something terrible is growing inside of him. Lando’s similarly perambulatory protagonist is confronted in the final panel by a reptilian counterpart, the ominous of the sudden meeting conveyed by superimposing a massive image of the creature’s head over the panel itself. CF’s contribution features a warrior in freefall and ends with the phrase “ENTERING ENEMY AIRSPACE” — it stops where the story starts, basically. Jonathan Chandler’s soldiers marvel after one of their fellows — “He really did it. He went out alone after the lights.” — whose journey to a cryptic series of what look like cardboard cutouts of robots or aliens remains unexplained. Many more pages are simply wordless images or wordless series of images featuring vaguely science-fictional figures doing vaguely science-fictional things. The tight space constraints offer the participants a welcome opportunity to step away from the typical worldbuilding concerns of alt/artcomix-genre hybrids and instead focus on world-evoking, a sense of what it would be like to be there, even when you don’t know what or how or why “there” is. The comic is printed in a flourescent orange and blue palette, like Cold Heat‘s pink and blue gone radioactive — a post-apocalypse run by a New York Mets memorabilia cargo cult. It’s a fine package and a delightful combination of form and function.

Comics Time: Powr Mastrs Vol. 3

January 7, 2011Powr Mastrs Vol. 3

CF, writer/artist

PictureBox, October 2010

112 pages

$18

Buy it from PictureBox

Buy it from Amazon.com

When thinking of CF’s revisionist-fantasy series Powr Mastrs, two things usually spring to my mind: Its psychedelic visual flourishes — both the precision and strength with which his wire-thin pencil line imbues them and the way such visuals feel like a natural part of any fantasist’s vocabulary — and its graphic sexuality — equal parts disturbing and erotic, serving perhaps as a substitute for violence, one that’s actually capable of shocking a modern audience. Unfortunately for me that’s often all I think about when I think about the series. But in re-reading all three volumes in preparation for this review, lots more jumped out besides. For one thing, this is a funny comic! From Subra Ptareo’s would-be monasticism to Jim Bored’s futile attempts to get someone, anyone to free him from his prison to the Sub-Men’s shenanigans, it’s frequently LOLtastic. It’s also a lot less rambly and more focused than I remember it: The overarching plot, about Mosfet Warlock’s weird science and various other characters’ attempts to use it for their own ends and/or seek revenge for having been its unwilling guinea pigs, establishes itself right quick and is a constant presence. And back to the sex for a second: It’s hot stuff! And it’s kinky in a way that feels genuine, which takes guts as well as perviness — the naughty part of this volume feels like it emerges from considered contemplation of dominance and submission and how much fun they can be even as they look fairly awful to outsiders. Meanwhile the specifics of CF’s SFF here — the biomechanics, the spellcraft, the bestiary, the economy, the worldbuilding, the whole nine — feel singular and yet still intelligble. What a pleasure to watch an artist make genre come to him and his interests and obsessions rather than the other way around.

Comics Time: Crickets #3

January 5, 2011Crickets #3

Sammy Harkham, writer/artist

self-published, December 2010

52 pages

$8

Buy it from PictureBox

In the past I’ve said the the solo alternative comic-book anthology series works great as an opportunity for developing cartoonists to experiment in front of an audience on a regular basis. That’s certainly true. But it also works great as a showcase for a confident, experienced cartoonist to show off his chops at a manageable but still considerable length — a star turn, if you will. Think the last two issues of Eightball, for example. And think Crickets #3. The bulk of this self-published issue of Sammy Harkham’s solo showcase is occupied by “Blood of the Virgin,” the story of a week in the life of a harried young father and hack in the stable of a fictionalized version of Roger Corman’s American International Pictures who really wants to make films, goddammit. It’s Harkham’s longest and richest exploration yet of his go-to themes: family as a series of unignorable demands on one’s time and emotions, and ethics and morality as a manifestation of how we deal with those demands. It offers him a seamless way to integrate the horror and trash-cinema influences he’s long displayed in comics like “Poor Sailor” and “Black Death” with the literary fiction he’s always championed as editor of Kramers Ergot but which has been overshadowed by that anthology’s artcomix and genre pastiches, not to mention his own. It gives him a shot at an Ignatz Series-style canvas in terms of trim size and two-color printing. It offers us page after page of his deeply pleasurable cartooning, which in its feathery line and dot-eyed clown-nosed character designs and alternately sinuous and bulbous lettering recalls old-timers like Gray and Segar and young turks like Crane and Huizenga while aping none of them. It enables him to sneak in non-narrative, artcomix-influenced visual flourishes completely diagetically — fog enshrouding a neighborhood during the small hours, a mushy plaster cast making a melted nightmare out of someone’s face, frank and kinky depictions of sexuality. It’s basically a just plain terrific alternative comic.

Comics Time: The Incredibly Fantastic Adventures of Maureen Dowd: A Work of Satire and Fiction

January 3, 2011The Incredibly Fantastic Adventures of Maureen Dowd: A Work of Satire and Fiction

Benjamin Marra, writer/artist

Traditional Comics, December 2010

24 pages

$3

Buy it from Traditional Comics

This is one of the most vicious and effective works of satire I’ve seen in comics in I don’t know how long. I say that as someone who pretty much loathes political and editorial cartooning of all stripes — an endless nightmare of preaching to the choir, taking complex issues and boiling them down to ideas and images with all the subtlety and insight of blowing the raspberry. By contrast, Benjamin Marra’s stroke of genius in The Incredibly Fantastic Adventures of Maureen Dowd lies not just in picking an unusual target, but in the pinpoint accuracy of hitting it — in knowing his target back and forth and hoisting her by her own petard. Dowd is justifiably infamous for her egregious gender stereotyping, which nearly always is done to portray conservatives as macho-man action figures and liberals as lactating girly-men (which means BAD), unless they’re women in which case they’re mannish (which also means BAD). In this regard and in many others — her use of schoolyard-taunt nicknames, her concoction of humorous dialogue between political players– Dowd herself basically is a political cartoonist, as she herself has said, and yes, I mean that pejoratively. Thus when I see her dolled up like some Cinemax super-spy sexpot, gun tucked in her garter belt as she balances writing a hard-hitting exposé of the Valerie Plame affair with getting ready for her big date with George Clooney — double-barreled mockery that hits her hard both for what she is and what she isn’t — I’m reminded of the words of countless Law & Order judges responding to hubristic defense attorneys objecting to how Jack McCoy just snuck excluded evidence into the proceedings: “You opened the door, counselor.” Revenge is sweet; my own political heel-turn of several years ago, time wasted believing this kind of horseshit and enabling the bloody-minded fools to whose benefit it redounds, makes it all the sweeter. Oh yeah, it’s also a traditionally kick-ass Ben Marra action comic. Keep your eye on his inks — there are places where it’s so thick and slick and shiny it’s almost Charles Burns territory. Fantastic.