Posts Tagged ‘comics reviews’

Comics Time: They Moved My Bowl: Dog Cartoons by New Yorker Cartoonist Charles Barsotti

January 23, 2008They Moved My Bowl: Dog Cartoons by New Yorker Cartoonist Charles Barsotti

Little, Brown and Company, May 2007

Charles Barsotti, writer/artist

120 pages, HC

$19.99

Buy it from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or Wal-Mart

In trying to approach this book like a critic, I feel like that giant Arab swordsman who tries to approach Indiana Jones: No matter what kind of fancy-pants technique I might show off, I’m just gonna get shot. I love dogs, and as such I’m helpless before this collection of Barsotti’s simply drawn gag cartoons revolving around our Canine-American brothers and sisters. A lot of the fun here is watching that New Yorker cartoon world of Freudian analysis on couches, mustachioed men in suits who call their briefcase-toting subordinates by their last names, and pairs of people tossing off neurotic bon mots to one another surgically implanted with puppies in the lead roles. There are various paths Barsotti takes within that basic map–dogs with human concerns, dogs treating doggie concerns like humans, humans treating doggish dogs like humans, puns, and so on; it’s amusing to see Barsotti recombine the constituent parts of, say, a boardroom gag or a courtroom scene depending on what species is placed in what position and in what ratio. While some of the very New Yorker-ish mixed-species gags are funny (the one where the human therapist says to his canine patient “And only you can hear this whistle?” totally cracked me up), I’d say that overall the best jokes are world-weary dog-on-dog bits (“Oh, God, am I housebroken,” says one recumbent puppy to his therapist) or mixed-breed efforts that play up the pathon, emotion, and sheer love of dog ownership. I lost it at the deadpan hyperbole and specificity of a human auctioneer gesturing to the tiny dog next to his podium and saying “The bidding will start at eleven million dollars.” Meanwhile, one gag that I simply refuse to spoil involving the reunion of a man and his dog in heaven had me crying at my desk in the middle of the afternoon, and I defy anyone who’s lost a pet not to do the same. The great thing about it, though, is that it isn’t at all maudlin; the body language of the characters involved makes them look completely unaware that they’re in a five-hankie cartoon.

Of course these aren’t all winners; some cartoons just don’t quite rise to the level of funny, and strange choices in terms of which cartoons to place on opposite pages of a spread lead occasionally lead to an immediate redundancy of ideas or execution. But Barsotti’s effortless cartooning, somewhere between Charles Schulz (a fan) and Gary Larson, is always a pleasure. I particularly like how he plays with the size of both props like desks and judges’ benches and the characters themselves depending on their relationship to one another (a gag about an old dog telling his frightened young employee that his tricks have served him well, thank you very much, works much better since the boss dog is about twice the underling’s size). It’s a funny book, sometimes a moving book, and good gravy it’s a great gift for a dog lover.

Comics Time: Big Questions #10: The Hand That Feeds

January 21, 2008Big Questions #10: The Hand That Feeds

Drawn & Quarterly, October 2007

Anders Nilsen, writer/artist

42 pages

$6.50

When I was a kid I was in Gifted class and we went on a field trip where some guy spoke to us about aliens and UFOs. He talked about how when eyewitnesses report UFOs hovering there one second and then being whoosh gone the next, it could be something similar to what a dog thinks happens to his master when the master gets into the car and drives to the supermarket. The dog’s brain isn’t sophisticated enough to understand that process–he just knows the master’s gone. Maybe the aliens are on a corresponding level to us as we are to the dogs.

That idea stuck with me for a long time. It’s only in reading this issue of Nilsen’s long-running series that it occurred to me that you don’t need aliens in that equation–you can basically just say that perhaps the meaning of life, what’s really going on here, just what the hell is going on with us, is just as much out of the grasp of our comprehension as how aliens commute. Nilsen, who since beginning this series has had to wrestle with the precarious nature of human life and our need to cobble some sense out of its ruins in a way I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy, articulates this notion gently and humorously in Big Questions, but also terrifyingly. His art is a repeated intimation of great vulnerability, with a line that looks like it might blow away in a strong wind, figures whose slightly disproportionate heads suggest infancy, heightened detail that sits mutely on the page indifferent to what plays out amid it, and a nightfall that coheres out of a multitude of tiny dots of darkness as though it can’t muster up the courage to simply descend. His rival flocks of finches and crows, in their interactions with themselves, each other, a pack of wild dogs, and a pair of human survivors of a catastrophic plane crash, grapple with the big questions of the title–quite literally in this issue, as one of them comes up with Plato’s parable of the cave–but always with one hand tied behind their metaphysical backs. There’s just so much they don’t understand about the crashed plane, the people, even each other. Their touchingly well-meaning efforts to stockpile food for “the hatchling” inevitably lead to grousing, mockery, rivalry, and finally violence. What makes the book so unsettling and frightening is that they’re really completely wrong about what’s going on, and both their good and bad intentions, their sacrifices and their sarcasm and their venality, are all equally meaningless. Is that what life is?

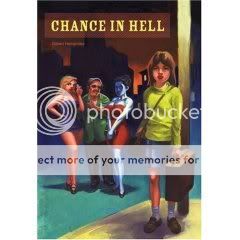

Comics Time: Chance in Hell

January 18, 2008

Chance in Hell

Fantagraphics, September 2007

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

120 pages, hardcover

$16.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

Rough, rough stuff from the creator of Palomar. Hernandez is in the midst of creating graphic novels based on the B-movies that his Palomar-verse character Fritz starred in, but “B-movie” might give you the wrong impression here. This isn’t one of those howlers the bots made fun of on MST3K–it’s the kind of disturbing, unpleasant film starring and shot by unknowns that you might rent on a whim from the horror or European section of your old neighborhood video store, watch, and spend the rest of the evening worried about the mental health of cast and crew. The story concerns Empress, an orphaned toddler abandoned in a sprawling, dog-eat-dog garbage dump and raped so frequently that she doesn’t even seem to notice anymore. A farcical string of bloodily violent incidents leads her to a life as the unofficially adopted daughter of a poetry editor who claims to have come from the same circumstances, and then eventually to a second life as the wife of a young district attorney, but in both cases violence and squalor cling to her like a stench, to use a frequently invoked metaphor.

This is the angriest I can ever recall Gilbert’s art looking. That’s saying something: My wife, for example, finds his books almost difficult to look at–“His characters just look so hard,” she says, and they’ve never been harder than here. Right from the get-go his figures seem dashed off as in a white heat, while several early landscapes and backgrounds in the hellish dump look like the whole world is on fire. His almost supernaturally confident pacing of scenes and the cuts between them evoke in their matter-of-factness the acceptance of everyday brutality by the characters themselves. At times the jumpcuts can be quite funny, as when a scene between Empress and her adopted father consists solely of a pair of panels where they argue over whether a glass is half empty or half full; both Hernandez and his characters know how reductive this exchange is, yet also know it’s quite true to who they are.

But when that metronomic editing slows down, the effect is powerful, particularly because it is often done to draw out scenes of gutwrenching violence or tragedy. (The centerpiece scene in the brothel is as disturbing as the death squad attack in Gilbert’s masterpiece Poison River; there as here a knowing glance is all-important, but here it causes murder rather than prevents it.) The end of the book changes the pacing again, revving up the jumpcuts to suggest unsolved crime and unglued minds, and to be honest I’ve revisited it three or four times today and I’m still not sure what’s going on. Maybe that’s a problem, maybe it’s not. Since I see myself revisiting this book, a gruesome, enraged commentary on just how shitty things can be, many, many times in the future, I’m leaning toward “not a problem at all.”

Comics Time: The Last Call Vol. 1

January 16, 2008The Last Call Vol. 1

Oni Press, August 2007

Vasilis Lolos, writer/artist

144 pages

$11.95

My favorite thing about The Last Call‘s debut volume is that it’s not at all what I thought it would be. I expected the kind of genre mash-up hipster-action/adventure/fantasy story we’ve seen in books like Scott Pilgrim, Multiple Warheads, East Coast Rising, and even Powr Mastrs to a certain extent. That’s where it seems like we’re going at first, as young metalheads Sam and Alec head out for a road trip blasting loud, evil music with hilariously Spinal Tap-esque lyrics that fill their car, and the panels, thanks to Lolos’s clever writing and lettering. Next thing you and they know, they get zapped into another dimension where they’re apparently on board an enormous train filled with monstrous beings who dress and act like characters from Murder on the Orient Express (an obvious influence, along with Paul Pope’s Heavy Liquid, two works not often paired). Then you’ve got to muddle through some claustrophobic layouts, staccato pacing, an unclear sense of place, and a somewhat repetitive choice of facial expressions for poor stranded Sam, who soon becomes our main character. (You definitely miss the levity and variety brought to the table by Lolos’s vivaciously inventive color palette in his Pirates of Coney Island series with Rick Spears.) But just when you think you’ve got the book pegged, there’s a moment when Sam’s sitting down for lunch in the train’s palatial restaurant with an enormous bulldog-jowled, double-mandibled dowager when suddenly you realize that Lolos is tapping another vein of fantasy entirely: the episodic discovery-of-another-world story. Sure enough, charming, slightly menacing characters collide with Sam to his alternating delight and chagrin, like an Alice in Wonderland or an Abarat as drawn by a guy with a lot of tattoos. The pacing gets increasingly clever, the character design and body choreography increasingly expressive, the plot increasingly hooky, and the book increasingly enjoyable. Like his frequent collaborator and real-life S.O. Becky Cloonan, Lolos is an exciting artist who should be a blast to watch as he shakes free of his most direct influences; this book’s a good start in that regard.

Comics Time: Skyscrapers of the Midwest #4

January 14, 2008Skyscrapers of the Midwest #4

AdHouse Books, October 2007

Joshua W. Cotter, writer/artist

56 pages

$5

The fourth and final issue of Josh Cotter’s stunningly self-assured debut comic is kind of like the thesis statement of the series. The rich fantasy lives of the two little brothers, shaped almost completely by the kind of throwaway genre entertainment of the ’80s that proved almost despite itself to be richly resonant with we America’s nerds and losers, virtually replace their emotions rather than be shaped by them. The younger brother’s innocently violent He-Man drama of loss and recovery, the older brother’s violently sexualized late-Marvel drama of emasculation–both larger-than-life sequences all but spill out of their pages and overwhelm the usually staid visuals of the book. In this way they’re like the mystical flood that sweeps away the boys’ grandmother in the mysterious shared vision that gives the series its title. The choice offered to the older brother in this sequence, itself the apotheosis of the mystical realist epiphanies whose singular iconography has given the series much of its power, is to keep a part of himself locked away behind the helmet of his damned superhero idol or face life without that iron mask. As you might know if you’re reading this blog, this comic like all comics is part of an industry where major players profit quite directly from lingering emotional scars and not always in the most scrupulous of ways, so the theme hit me square in the gut. Skyscrapers #4 is both uncondescending and uncompromising in its depiction of how fantasy can be both pleasure and prison. It’s a hard and beautiful book, and aside from a slight misstep involving a too easily provoked and resolved fight between the brothers at the book’s end, which is the kind of thing I’m very forgiving about, it’s a fantastic book too.

Comics Time: Incredible Change-Bots

January 11, 2008Incredible Change-Bots

Top Shelf Productions, August 2007

Jeffrey Brown, writer/artist

144 pages

$15

The best gags in Jeffrey Brown’s loving, lushly colored Transformers parody feel like they didn’t necessarily have to be part of Jeffrey Brown’s loving, lushly colored Transformers parody. A Change-Bot describing, mid-fight and in overly verbose detail, the rigors he went through so as to enjoy pounding the shit out of his enemy…a leopard batting around an origami Change-Bot, then “trot trot trot”ting away with the crumpled bird-bot in its mouth…the evil leader blowing away his underling for the crime of having “perfect aim” that’s “not perfect enough”…all of these jokes play off the same sources of humor–inflated self-worth either rampaging unabated or getting pathetically deflated, imaginations shaped by exposure to genre fiction–present in many of Brown’s gag panels and short, funny stand-alone strips.

The story that links them all together is definitely best appreciated by Transformers fans, and I’d imagine Brown didn’t hope for anything more. That two factions of giant robots waging vindictive war against one another for eons might unwittingly cause massive destruction to themselves and their allies in the process is an idea that even kids could dimly make out beneath the surface of the concept, and Brown brings it to the fore entertainingly, maybe all the more so for its gentleness (Dan Clowes’s “On Sports” this isn’t). He also makes some hay out of the narrative loose ends endemic to these kinds of stories: robots yelling “I can explain!” and never doing so, doomsday buttons that may or may not have been pressed. If anything, I wish he’d laid into some of the Transformer mythos’ weirder elements–those five-headed floating robot tribunal guys, the giant planet-sized robot, the death and rebirth of the two leaders, and so on–but I suppose that would draw it away from the central “two equally stupid and destructive forces are arbitrarily slapped with ‘good’ and ‘evil’ tags and the audience is expected not to notice” thesis.

Ultimately Change-Bots is dumb fun, with the emphasis on both words: Practically every character is an idiot, which limits the book’s depth. But when combined with Brown’s solid character design, blockily effective action choreography, and vivid magic-marker palette, it’s certainly a pip to breeze through, even if I don’t see myself returning to it as often as I do to Brown’s autobiographies, or even most of his other, less franchise-specific humor and parody comics.

Comics Time: Multiple Warheads #1

January 9, 2008Multiple Warheads #1

Oni Press, July 2007

Brandon Graham, writer/artist

48 pages

$5.99

(I hope you’ll pardon me for getting meta for a moment. Normally I think talking about trends when discussing a comic like this is just a substitute for actually discussing the comic, but in this case the meta takes us in a direction my mind’s been wandering in a lot lately anyway.)

I don’t know if it’s fair to credit Scott Pilgrim as throwing wide the doors for projects like these, or if it’s simply the highest-profile such project to pass through said doors regardless of who might have opened them. But at any rate, Multiple Warheads is one of those books like SP that makes you say “hey, this is an exciting time to read comics.” Like a growing number of projects–many from Oni–it’s the product of a North American artist who’s interested in action-based genre storytelling yet has no particular debt to superhero comics, a creature that until recently didn’t exist. In this case the artist is Brandon Graham, and he’s bringing to bear obvious interests in manga, European sci-fi comics, barbarian stories, and porn to create a fast, loose story of a waaaaay post-apocalyptic future where a va-va-voom young lady named Sexica smuggles super-powered organs around a walled-off city inhabited by aliens and werewolves and normal people too. It’s a pretty slight thing. Maybe that’s because the most obvious points of comparison–Scott Pilgrim, East Coast Rising, The Pirates of Coney Island–are all telling book-length stories while Graham’s going done-in-one (and at kind of a hefty price point). Or maybe it’s because the thin line, skewed proportions (everything seems both a bit narrow and a bit bowed), and acres of blank space in the word balloons give the art a tossed-off barely-there feel. Or maybe it’s because the story isn’t really a story per se, it’s more of a “day in the life” kind of thing that simply begins when it begins and ends where it ends, arc schmarc. But the end result of all that slightness is not unpleasant in the, well, slightest. It’s a breezy vibe for a breezy character. Indeed, breeziness is very serious for Sexica, almost a raison d’etre. She wants to go someplace nice, untouched by war, and she’s tried to get there, it seems, through means both intimate (sewing a smuggled wolf dick onto her boyfriend for some extra spark in the sack) and direct (taking advantage of a spaceship crash to get the hell out of Dodge). It’s a laid-back book, almost a stoned book, which makes sense given that Vaughn Bode is evident in Sexica’s every lovingly delineated curve. I enjoyed it, and I’m hoping that future issues will provide some muscular mind-expansion–something along the lines of the beautiful panel that communicates Sexica’s post-coital bliss at being surrounded by the comforts of home with a bed’s-eye-view of the bulbous light fixture on the ceiling above her–to deepen and enrich the pleasures of this installment’s lovely but fleeting buzz.

Comics Time: Batman by Josh Simmons

January 7, 2008Batman

self-published

Josh Simmons, writer/artist

16 pages

Read it for free at joshuahallsimmons.com

This haunting, completely unauthorized take on Batman begins with what may be the best first panel of a comic I’ve seen in the past year: A crazed jumble of a cityscape whose non-Euclidean geometry resembles something out of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari threatens to overwhelm the panel borders and spill out all over the reader, while a caption box identifies it, simply and confrontationally, as “Gotham City.” That sets the tone for what follows–a disturbing, uncomfortable response to the Batman concept. What really knocks me out is just how many different levels it works on. It could be a horror comic in about a human monster in the Henry/Buffalo Bill/Leatherface vein. It could be a blackly humorous, satirical pisstake on the Caped Crusader. It could be a vicious assault against the reactionary politics of the superhero. It could be an angry riposte to the ever-grittier direction superhero comics are headed in. It could be an exercise in drawing action and environments. Most amazingly, it could be a great Batman comic, period–Batman’s rooftop and skyscraper milieu is depicted with genuine awe, the physical particulars of his methods are choreographed impeccably (as good as any comic this side of Paul Pope’s Batman Year 100), and the story is totally convincing as an examination of what might happen if Batman, worn down by the weight of years of horror and toil–“I’ve been Batman for a long time,” he repeats–finally snapped. As in his horror graphic novel House, Simmons’ art excels in conveying the way the sheer size of environments both natural and manmade can be frightening, and as his inks shift back and forth from woodcut chunkiness to manic clarity, the effect is practically palpable. The pacing is ruminative but never plodding, lingering just a bit too long, making you feel like something is off but never tipping its hand till the story demands it. Clever bits of business involving Catwoman’s acrobatics and the passing of a nearby plane add pizzaz to an extremely dark affair. Even Simmons’ figures, never his strong suit, have the mitigating factor of masks and costumes working in their favor. And on a meta level, it’s just exciting to watch an artist steal a major corporate icon because he’s got something to say and needs him to say it. This is a hard comic to shake, so thank goodness I have no intentions of trying to do so.

Comics Time: Powr Mastrs Vol. 1

January 4, 2008Powr Mastrs Vol. 1

PictureBox Inc., November 2007

C.F., writer/artist

120 pages

$18

It might be the jellyfish-on-human double-penetration tentacle-sex scene that makes you realize that this is an adult fantasy comic, but that label, “adult,” is really present throughout this first in a projected series of chronicles of the land of New China. For all that characters like Subra Ptareo may be on a quest and Mosfet Warlock may be a mad scientist, their interlocking stories (so far) don’t read like the genre narratives of my youth beyond their fantastic trappings at all. Instead, they’re stories about buying things and selling things, about twentysomethings (or at least twentysomething analogues) meeting new people and flirting with them, about getting stoned, about fucking and deceiving the people you fuck, about being moved to tears by the realization that you’re actually good at what you’ve chosen to do with your life. Where the fantasy really comes in, for me at least, is in the art. C.F.’s simple, childlike line is reminiscent in affect and effect of Frank Santoro’s in their mutual publisher’s Cold Heat, but while the latter relies on open spaces and canny color choices to evoke the both the supernatural and the mental states akin to it, the former gets it done with detail. The result is always shocking, whether a sudden splash page overripe with flowers and foliage or a doggystyle-eye-view close-up of a tentacle-filled vulva. The word I’m really looking for here is psychedelic, not the cheesily amorphous lowest-common-denominator version but the intense wall-of-sound riot of art-information present in a Moscoso font or the crescendo in the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life.” The combination results in as fecund a playground for the imagination as a far more traditional fantasy story, but arrived at from a totally different direction. It’s inspiring.

Comics Time: Kid Eternity

January 2, 2008Kid Eternity

DC/Vertigo, February 2006

Grant Morrison, writer

Duncan Fegredo, artist

144 pages

$14.99

So this must be one of those “minor works” I always hear so much about. Collecting the three-issue 1991 Vertigo “reimagining” of some old DC character, Kid Eternity reads like many a current comic really intended as a movie pitch rather than a reading experience: A hapless everyman is inducted by a glib, ubercompetent, superpowered cool dude into the secret truth behind the world as we know it. The pleasures to be had here are in the idiosyncratic details Morrison weaves into this shopworn plot: casting said everyman as an observational stand-up comic (his name, Jerry Sullivan, evokes a Seinfeld with an Irish-Catholic’s hang-ups instead of a Long Island Jew’s); making said secret truth a weird (if familiar) splatterpunk take on Dante’s Inferno; harnessing artist Duncan Fegredo, who currently mimics Mike Mignola in the pages of Hellboy, to the yoke of the world’s lengthiest Dave McKean impression. But the curveballs failed to keep me as too many of the surrounding pitches were predictable and almost half-hearted. Serial killer? Check! Deranged Christian missionary? Check! Crazy lettering? Check! Tarot cards? Big check! Fegredo’s visuals feel similarly lackluster: For every memorably wild vista (his infernal architecture is particularly ambitious) there’s a murky, difficult-to-follow action sequence (I’m still not quite sure what happened in that initial bloodbath), hard-to-distinguish supporting character (I didn’t notice that there were two separate murderous antagonists for Jerry and the Kid until they started attacking one another), or just generally uninspired choice (a would-be mindblower tour of hell is metonymized by a few static stand-alone panels and one image seemingly picked at random to anchor the spread in the background). Morrison’s at his best when his comics either really read like comics (Arkham Asylum, All Star Superman) or look like comics (We3, I dunno, Seven Soldiers), and this comes across as a creature of its era that thinks it’s too cool for school to do either, which it isn’t.

Dan, just admit it… (or: a spoiler-filled analysis of Eightball #23)

June 29, 2004Foreword: Petty patronizing hyperbole aside, my pal Milo’s recent posts on the preponderance of superhero-centric writing in the comics blogosphere has had at least one positive effect: convincing me to get off my duff and blog more often about alternative/art comics. But the altcomic that I’d like to talk about today also happens to be a superhero comic. Dramatic irony, or poetic justice–you make the call! Also, SPOILER ALERT.

Eightball #23

Daniel Clowes

44 pages, full color, $7.00

Fantagraphics

Okay. When I said Daniel Clowes’s new comic, Eightball #23: The Death-Ray was a superhero comic, I was exaggerating a bit. Oh, sure, it’s an explicit response to the genre–a critique, even–but it properly belongs to another maligned type of genre fiction: the serial killer narrative. The superhero trappings throughout this pitch-black work provide an easy in for discussion, not to mention one of Clowes’s trademark meta-references to the history and ephemera of the medium in which he is so alarmingly proficient, but in the end The Death-Ray is about superheroes in the same way that The Silence of the Lambs is about psychiatrists. The professional inspiration of the killer is interesting, but it’s the fact, the existence, of unflinching, unreflective evil that’s the point.

The Death-Ray‘s protagonist is Andy, to whom we are introduced when he’s a twice-divorced middle-aged dog owner, but whom we mostly follow during his years in high school. (In fact, we’re not even sure we’re following the same guy, at least initially; I had to go back and reread the opening high-school sequence (“The Origin of Andy”) before I realized that the brown-haired, skinny kid in it was, in fact, not a girl.) Andy is a quiet, nondescript kid of no discernible social strata in his school, whose only friend is bespectacled, somewhat arrogant crypto-Nietzschean student named Louie. Raised by his aging and ailing grandfather following the deaths of his father, mother, and grandmother, Andy discovers upon smoking a cigarette (one he initially thought must have been laced with PCP) that he gains superhuman strength with the introduction of nicotine into his bloodstream. A letter addressed to him from his late scientist father explains that this incredible power is a result of an experimental hormone he treated Andy with during his childhood. It also reveals the existence of another experimental weapon: A yellow gun resembling a science-fiction blowdryer, that fires something referred to by Andy’s dad as a death-ray. We soon learn that when Andy (and only Andy) pulls the death-ray’s trigger, whatever he aims it at is erased from the face of the Earth. With the advice and encouragement of Louie (who, following a trip to New York City, has become enraptured with the exhibitionistically angry punk movement), Andy sets about finding a way to use his newfound powers for good, in pursuit of the “something big” for which he feels his tragedy-laden life has destined him.

And oh, geez, where to go from there. Eightball #23, like its predecessor #22 (Ice Haven), is a staggeringly rich and dense work. Like #22, #23 is divided into numerous subsections of varying artistic styles, each with its own old-fashioned sub-title. Unlike #22, though, #23’s subsections would be difficult to understand if read on their own; the individual titles are less a mechanism of the paradigmatic writing method involved in the previous issue (in which individual vignettes about various characters cohered to tell an overall story, a la Altman) and more a convenient method of simultaneously transitioning from one scene to another, setting up and/or commenting on the scene at hand, and tying the entire work back to the superhero and melodrama genres with which Clowes is constructing his new work.

Primarily drawn in a slightly looser, sketchier style than is customary for Clowes, the art of The Death-Ray conveys a sense of terrible urgency, as though this was a story Clowes felt he had to tell as soon as possible. (This despite the two-year gap between issues—it sure doesn’t feel like it’s been that long.) Switches between one style and another are not done with the rigorous regularity of #22; there’s less of a sense of “I’m aiming for something different with this section” and more of “this is just the most efficient way for me to keep the story going at this clip.”

The primacy of the need to get this story out is reinforced within the narrative itself by the way Clowes has Andy, the book’s narrator and in almost every scene its focal character, tell us the story. Rather than using traditional thought balloons or thought caption boxes, Andy’s thoughts and narration are contained in actual word balloons. There is a slight difference between the balloons that contain narration/interior monologue and the balloons that contain actual—the former are slightly rectangular, the latter have the usual rounded shape—but the overall effect is that wherever Andy goes, whatever Andy does, his personal view of the world is not just inescapable but dominant. It’s a brilliantly evocative technique, familiar to any reader who’s ever gone through the motions of interaction with others yet spent the whole time in his or her own head. (As Andy puts it, not of his way of thinking but of his use of his superpowers, “somebody has to impose some kind of structure on the world, I guess. Otherwise everything would just fall apart, wouldn’t it?”)

Andy, then, is very much the star of his own movie. That is also one of the themes of the book: The degree to which pop culture molds individuals’ expectations of themselves. Andy’s adoption (largely at Louie’s behest) of a superhero’s costume and vigilante techniques make next to no sense given Andy’s actual life experience, even given the incredible introduction of superpowers into it; after all, Andy surmises that his father simply intended for his son to become as strong as the athletic kids in his grade and “turn myself into the most popular kid in school.” It’s the boys’ exposure to funnybooks and, one assumes, the Batman TV show, that convinces them to use Andy’s super-strength and death-ray to fight crime, such as it is. The multiple sub-titles that Clowes assigns various sections of the book—”ON PATROL,” “THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF THE DEATH-RAY,” “THE LAST STRAW”—further drive home the artificially constructed nature of Andy’s self-perception. Moreover, the occasional sequence depicts Andy and Louie swinging along city rooftops and battling crooks in the traditional superhero manner, even as they themselves continue discussing the far more quotidian battles in which they’re engaged. (The occasional “Right again, old chum!” is thrown in, but only to demonstrate the depths of the budding psychosis; we know that this was not spoken aloud, but it’s no less an accurate depiction of Andy’s mindset for that.) And it’s not just mass, mainstream culture that’s to blame, by the way. Louie’s cookie-cutter punk outlook is as much a catalyst in the terrible events that follow as is the boys’ familiarity with superhero tropes, since it gives Louie’s preexisting contempt for nearly everybody a cultural framework in which to thrive. Punk does little more for Louie than providing him an avenue to get laid, making him a bigger asshole than he already was, and giving him an excuse to pick fights—which he then cites as proof that other people are assholes who deserve what they get.

Indeed, the real problem besetting Andy and his supposed sidekick is the arbitrariness of their actions in combating crime and bad people. Simply put, the disconnect between the crimes committed and the punishment Andy and Louie dish out is so great that the act of punishment itself becomes meaningless. Andy and Louie use a discarded wallet as bait, then bully the impoverished man who picks it up, committing a “crime” that couldn’t even have occurred without the boys’ intervention. Andy roughs up a couple of burglars who he spies running off with an old man’s TV set, but even before he catches up with and knocks the snot out of them, they’ve dropped the TV, destroying it; it’s clear from the old man’s expression that he can’t afford to buy another. A girl Louie has the hots for gets smacked around by her father; Louie and Andy beat the man, but do so as he’s walking the girl’s beloved dog, who runs away, thus making her even more upset. Louie constantly tries to persuade Andy to have at a high-school meathead named Stoob with whom Louie has a long-standing and incredibly stupid grudge; it gets to the point where Louie lies on the sidewalk motionless in front of Stoob in hopes that the kid will kick him, in order to “prove” that Stoob deserves to die. In a sequence that quietly hits home for the grown-up Andy, a bartender is rude to a man who’s drinking because his grandmother died that day; Andy subsequently beats the oblivious barkeep to a bloody pulp. The beginning of the end for Andy and Louie occurs when Louie’s resentment toward his sister Teresa’s drug-dealing boyfriend leads the boys to indulge Teresa’s ex’s semi-veiled request to take the man out permanently. As Louie, abuzz with newfound moral qualms, puts it to Andy after the event, “You know, C.J. was an asshole, but he didn’t deserve to die. You didn’t even know the guy.” This from the kid who came up with the whole idea in the first place, as Andy immediately points out to himself. Louie may have had enough, but by now Andy is too far gone, too attached to the notion that he finally has the ability to “impose structure on the world,” to stop.

So at last we come to the heart of Eightball #23’s darkness: We’re witnessing the birth of a serial killer. Murder has never been far from the surface of Clowes’s work—with the exception of Ghost World, all his major works have contained violence or the threat of violence—but this is his most thorough (and not coincidentally his bleakest) examination of the subject to date.

The day before I bought this comic, I used my employee discount to pick up Michael Newton’s The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. In it, Newton quotes a jailhouse monologue from prolific serial murderer Henry Lee Lucas:

It’s a damn shame about people, it really is. We are surely the ugliest creatures in all of nature. Look at you: What have you ever done? What gives you the confidence to sit there with a smirk on your face like you’re better than me? You think anybody cares about you? Guess what—they don’t. You can lie to yourself all you want, but the rest of us are wise to your scam. You should have been an abortion or sold into slavery. Who gave you the right to take up space in my world? I’ve never done anything to anyone they didn’t deserve. My justice is nothing if not merciful. Does that mean I’m soft? Hell no. You think I’m afraid to erase you from the landscape? Look, I know what you’re thinking. Hell, maybe you’re right. It’s a lot of responsibility, but I’m not one to complain. I’ve got a job to do like everyone else. Who am I? Your worst nightmare.

Chilling, horrifying…and fictional. That wasn’t Lucas at all, but our hero Andy, toward the end of the book, in one of the strongest sequences Clowes has yet created. Throughout this grotesque monologue the present-day, middle-aged Andy’s “mask of sanity” remains intact: He returns from the grocery store, puts away his food, strolls over to his closet, reaches inside, walks up to his apartment building’s roof, surveys the green below him, eats his TV dinner. It’s only just now, after several readings of the book, that I’m realizing that the thing he reaches into his closet to grab is the death-ray, that his talk about “eras[ing] you from the landscape” is no idle chatter, that the bell-shaped silhouette in the eighth panel of this sequence is not the doorknob to Andy’s apartment but the muzzle of the death-ray as outlined against the evening sky, and that the man sitting on a park bench below Andy (the appearance of whom made me nervous, in a Charles Whitman-referencing sort of way, but little more) has just become his next victim. The insipid banality of the Rambo quote that ends the passage merely heightens the horror: Andy has no real insight into why he does what he does beyond the cheesy vigilante morality of Hollywood.

And this momentous act is not the only one that happens in a caesura. At the end of the book we see a partial line-up of Andy’s victims, answering the section’s sub-title’s question, “Why did Andy destroy you?” We learn that the two divorces Andy has spoken of having were caused by men with whom Andy’s wives cheated, men who Andy then murdered. We learn that a brief conversation between the teenaged Andy and his housekeeper, in which the housekeeper implied that her daughter had been taking drugs, led to the execution of a man whose crime was nothing more than selling the daughter some weed. In the same way that the disturbing crime at the heart of Eightball #22, as well as its resolution, took place between the panels, so too do many of the killings in #23. It’s as though, to our central character, they’re hardly worth mentioning—the events he does choose to depict are assumed to be explanation enough. Given the circumstances, Andy seems to suggest, any one of you would have done the same.

As with nearly all serial killers, sex is a key component of the killings, although not as obviously as with some. Most serial murderers hunt within the gender to which they are sexually attracted (as an aside, this gives lie to the notion that The Silence of the Lambs is homophobic: Buffalo Bill is not gay at all, but a woman-hater whose transsexualism is intended as a mockery of both homosexuals and women; we even see Polaroids of the guy with strippers at one point). This is not the case with Andy, as near as we can tell’he maintains an idealized long-distance relationship with his “girlfriend,” Dusty (“I hadn’t stopped loving her—and still haven’t to this day, come to think of it,” he says 24 years later, though once again this is likely just an attempt to assign meaning to a life where none has truly existed). But he displays true, romantic feelings (which it nonetheless appears he is trying to hide from the reader; he never describes them to us, and the one time he does address them directly in the context of a dream about having sex with her, he talks to her (“you”) directly) toward his African-American housekeeper. Clowes clearly wants us to see this attachment as an integral part of what makes Andy into what he becomes. The key sequence in which Andy discovers the truth about his superhuman inheritance from his father, “THE ORIGIN OF THE DEATH-RAY,” begins with two panels of disembodied sexual dialogue (“Fuck me, Andy!” “Yeah, baby—that’s it!”), and eventually includes yet another (“Oh Andy, you fuck me so good!”). It’s not until two-panel daydream sequence pages later that we learn the idenity of speaker: Dinah, the housekeeper who keeps the place from falling apart as Andy’s Pappy becomes more infirm. Andy eventually makes his feelings for Dinah clear to her by attempting a kiss; by the very next panel, she’s gone, and the placement of this sequence just before the most traumatic one in the book implies a causal relationship between Andy’s actions in the former and his actions in the latter.

Similar goals influence Louie’s behavior. Right after a scene in which he and Andy discuss their lack of superheroic motivation (“Look at the Hulk—his wife died, or something”), Louie spots the girl on the basis of his crush on whom he and Andy would later assault her father. It’s Louie’s later discovery of a pretty punkette that leads to the moral conversion that catastrophically unravels his relationship with Andy. (Yes, the “one friend in the world” the grown-up Andy refers to is not Louie, to our surprise.) Moreover, nearly all of the victims of Andy we know of have some sexual connection to him, whether they’re the men who ‘fucked his wives” or the dealer who sold grass to his beloved housekeeper’s daughter. And finally, of course, there’s the unspoken sexual dimension of Andy and Louie’s relationship itself. Paired killers are not at all uncommon, from the Hillside Stranglers to Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole, and often the killings serve to consummate the sexual tension that the killers themselves aren’t (or, sometimes, are) willing to consummate themselves. It’s no coincidence that, just before Andy and Louie’s traumatic “break-up,” Louie seems to have found an actual girlfriend and Andy has finally acted on his love for Dinah. The two don’t need each other anymore. (It’s also no coincidence that the one scene we see without the interceding viewpoint of Andy is of a weepy Sonny, Louie’s sister’s lovelorn ex-boyfriend and the man whose desire to win her back sets the ultimate breakdown between Andy and Louie in motion. In the world of serial murder, love and death are inseparable.)

Of course, Clowes’s usual pitch-black insights into the human condition are omnipresent. Whether it’s Pappy’s cri de coeur (“Oh God, why can’t I remember things?”) and his inability to recall that his wife Sarah has died (“Dear S” reads his unfinished letter to her); Andy’s “girlfriend” Dusty’s tragicomic pose with a garden hose, using it as a microphone, lipsyncing to the radio with braces on her teeth; carrot-topped Stoob’s sensitive acoustic-guitar wooing of a pretty girl; Louie’s pre-NYC assessment of punk music (“You like this?” “I dunno…I think so. It makes me want to kill somebody.”); the fact that the mechanism Andy’s dad chose to activate his latent superpowers will likely give him lung cancer….You’ve got to laugh to keep from crying. It all culminates Andy’s closing address to the reader, delivered on what we assume is the Fourth of July after a run-in with a grown-up Stoob (you can insert the de rigeur “It’s about Iraq!!!” reading here, if you absolutely must):

He couldn’t fool me. Underneath it all, he was still the same guy. Nobody ever changes.

That’s not to say that everybody’s an asshole. I know better than that. Hell, you’re probably a decent person yourself. There are plenty of you out there.

For you, Mr. and Mrs. Decent Citizen, I’ll do anything. Just say the word.

You’ve got a friend in old Andy.

Of course, we don’t. But in the same way that Andy’s thoughts superimpose themselves against the events of his life, it’s Andy’s view of The Way Things Are, not ours that has the final say. Andy’s among us, and we’re his one friend in the world. Maybe he is our worst nightmare, after all.