Posts Tagged ‘comics reviews’

Comics Time: Fox Bunny Funny

June 11, 2008Fox Bunny Funny

Andy Hartzell, writer/artist

Top Shelf, June 2007

106 pages

$10

This very good funny-animal comic stands out from the anthropomorphized pack because its visual metaphor strengthens the impact of its more outrageous moments rather than diluting it. Anyone can get some mawkish sentimentality out of casting a cuddly critter in their tale of modern urban ennui, or flip the script and go for some guffaws by doing the umpteenth Fritz the Cat mammals-with-mammaries sex farce. Hartzell aims elsewhere in Fox Bunny Funny.

The first highlight is the violence. We meet our fox protagonist as an awkward adolescent in a broadly drawn conformist suburbia of sitcom vintage, where his fellow foxes kill and consume bunnies with gusto. When our hero is discovered hopping around behind closed doors wearing a bunny costume (I’ve gotten caught doing worse), he’s shipped off to a fox-scout camp where he’s trained to use an impressively horrible beartrap-shooting weapon on bunny-shaped bullseyes. When he proves an excellent marksman, his scoutmaster drags him along on a bona-fide hunt…to the town where the bunnies live with all the same civilizational niceities as the foxes. Hartzell depicts their rampage with disturbing imaginativeness–the foxes run bunnies in cars off bridges, plow through restaurants in their SUV, then smash their way into a bunny family’s home, burst in on their Anne Frank attic hideout, and slaughter them. Eventually the hero flees to a bunny church (the suffering of the bunnies analogized to the suffering of Christ), but when he’s discovered frolicking with the congregation by his fellow scouts, he can’t take the pressure and leads the slaughter himself. Obviously, making both predators and prey into human-style civilizations heightens the savagery of the foxes’ attacks on the bunnies. It may be a metaphor for war or racism or meat-eating or all three at once; mostly it comes across as a refreshingly harsh indictment of human brutality and stupidity in all its forms.

The second strong point is the depiction of a shared fox-bunny counterculture. After the murder in the church, we join our hero years later, where he’s a perfectly normal member of the bunny-eating masses. When a bunny prankster attacks his house, he’s led on a chase through the proverbial and literal rabbit hole into a West-Village-meets-Haight/Ashbury urban freak mecca, where bunnies and rabbits of all genders mix and mingle enthusiastically. Hartzell saves some of his most exciting cartooning for this sequence, including a Where’s Waldo/Hard Boiled-style two-page spread of the scene. What’s special here is that comics, particularly alternative comics, takes the existence of a counterculture for granted. Hartzell sets up the structure of Fox Bunny Funny in such a way that the discovery of this counterculture feels like a legitimate revelation. Do you remember when you were younger, and you first started pursuing countercultural interests and hanging out with the freaks or ‘bangers or emo kids or skaters or whatever they were where you grew up, or first journeyed to a big city and saw that people could be weird or gay and not be looked at like zoo animals for it, and this simple fact felt like both an explosion of self-liberation and a massive “fuck you” rebuke to society at large? Hartzell nails that. And then he goes one step weirder and more asseritve with the conclusion. All with impeccable, wordless kids’-book cartooning. I think I love this comic.

Comics Time: Aqua Leung Vol. 1

June 9, 2008Aqua Leung Vol. 1

Mark Smith, writer

Paul Maybury, artist

Image, April 2008

208 pages

$17.99

Here’s a book you can’t help but compare to other, similar projects that are mining this same vein of ad-hoc epic and homegrown myth(os)-making. Consider it the “A Star Wars of One’s Own” school. (I’ve dabbled in it myself.) The book I kept thinking of when reading it is Mouse Guard. This one comes out on top in virtually every way.

First of all it’s the rare independent comic that comes equipped with not one but two editors, including one seemingly solely dedicated to copyediting. And man, does it help! The story is a coming-of-age hero quest that frequently indulges in knowingly arcane dialogue, and it’s really easy to aim for “fancy” and end up hitting “gibberish.” This doesn’t happen here, which is a blessing right there.

Second, there’s Paul Maybury’s art. Don’t get me wrong, I think Mouse Guard‘s Mark Peterson is obviously a gifted illustrator, and also a better sequential artist than he perhaps might get credit for. But Maybury is something of a revelation here, his thick brush line (apparently this is his first-ever brush art!) at different times approximating the Paul Pope-Becky Cloonan art-blob vibe, the more manga-inflected Vasilis Lolos punk-action thing, some Bryan Lee O’Malley-isms in the character designs, and–out of left field–almost Fort Thunder-ish use of images-as-texture (a wall of “STOMP” sound effects, a two-page spread of arrows, a splash page consisting solely of clashing colors, and an opening map that looks like Ron Rege drew it), occasionally peeling back to an effectively crude, almost childlike minimalism. Colorist Russ Lowery is a break-out star here too, combining Lolos’s candy-coated palette with Dave Stewart’s subtlety and lushness. Smith’s script gives the pair plenty of room to play, with almost abstract combat scenes and bravura sequences like the Spaceball One-sized sea-monster whose jaws take fully four pages to traverse our viewpoint.

Speaking of Smith, he brings a most welcome sense of humor about the grandiose nature of this project to the table, something Mouse Guard lacks entirely. Will you wish he hadn’t kept The Hero with a Thousand Faces next to his laptop as he wrote this story? Sometimes, yeah. (Enough with the fucking absent father figures already, genre writers of America!) At first the epic saga-osity of the material gets the better of him–he burdens the story with something like four introductory sequences, and lets an omniscient narrator tell things that should be shown early on. But the structure smoothes out as the book goes on. Meanwhile he frequently undercuts any portentousness with a wink and a nod to his diverse sources, from the inclusion of a little octopus sidekick that feels like something out of a Japan-only video game to shots of the titular young hero peeking up girls’ skirts, flashback-sequence from Splash-style. And the approach to the violence is more Indiana Jones than Star Wars, if that makes sense–while it does move the plot and is supposed to inspire the awe of any good action sequence, it also unfolds like a choreographed routine and draws attention to that fact. What’s more, he sticks the landing with a climactic battle that feels climactic yet also naturally subservient to whatever will happen in the subsequent volumes.

Overall there’s really nothing here that leaves you feeling like everyone involve needs to get out of their parents’ basement in some fundamental way–it feels like grown-ups knowingly playing with their old action figures more than grown-ups trying to pretend that those action figures are for grown-ups. Nor does it mistake the modest aim of telling the story of its creators dreams for the delusional grandeur of Telling The Story Of Our Collective Unconscious. And oh yeah, the lettering and logo by Fonografiks is really kinda perfectly METAL. I even like the paper and cover stock. It’s a good time.

Comics Time: The Aviary

June 6, 2008The Aviary

Jamie Tanner, writer/artist

AdHouse, June 2007

312 pages

$12.95

I was challenged and intrigued by the idea of, and the ideas in, this debut graphic novel, comprising various interlocking minicomic and anthology strips. “The Aviary,” as we slowly come to realize, is a term for a strange, insular city peopled by various subconsciously resonant weirdos: an art-porn impresario who is also an anthropomorphized monkey, a sexy but viciously nasty receptionist, a limbless stand-up comedian, and so on. Popping up throughout is a blinking bird-headed doll/automaton called the Silent Bird-Man, alternately a symbol of reproachful authority and libidinous secrecy. Some clever shifts in the temporal order of the events being presented lead to a mobius-strip vibe reminiscent of one of David Lynch’s psychogenic fugue films; yes, it’s a shorthand way to connote depth and weirdness, but it’s an effective shorthand way to do that. On a script and story level, the project falls somewhere between Ed the Happy Clown and Asthma, not nearly as assured as either (easy anachronism is a sure-fire way to lose me, comics writers of America), but promising for how it plays with those tools.

The problem is the visuals. Tanner’s pen-and-ink line is reminiscent in some ways of Rick Geary’s–not least because of its old-timey affectations–but his overall sense of page design and panel framing lacks Geary’s inventiveness and storytelling brio. I think literally every single shot of every single character in the book is either head-on or in three-quarter profile, like they’re spending the whole book cheating to the audience. And they’re almost always shown in close-up or medium-shot–seriously, you’re as likely to see feet here as you are in a Michael Turner comic. The combined effect simultaneously makes the comic feel artificial and saps it of its energy. This is all compounded by an overuse of word balloons and figures that break the panel walls for no discernible reason, again making the images feel stagey. Meanwhile, the character designs blended together for me, making the already byzantine plot even more difficult to follow.

Overall, this is what you’d call a promising debut, but not in the blandly complimentary way that’s usually said–I really mean it’s noteworthy for the promise it demonstrates with regard to potential future works. What I’d like to see is Tanner throw this against the wall hard, to see what sticks, to see what’s broken, and to see how he can put something new, different, and better together with the pieces.

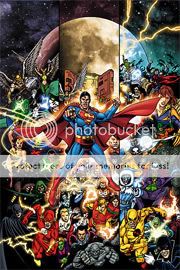

Comics time: Final Crisis #1

June 4, 2008Final Crisis #1

Grant Morrison, writer

J.G. Jones, artist

DC, May 2008

40 pages

$3.99

I first read this while standing in Jim Hanley’s Universe during my lunchbreak the day it came out. My first impression was basically flat. Brief, largely undramatic scene after brief, largely undramatic scene featuring a myriad of unconnected characters from across the sprawling DC Universe–a product of hundreds or thousands of writers and artists over going on eight decades, cobbled together by corporate fiat…there was certainly a lot going on. It’s got to be the most continuity-heavy Major Event launch…well, ever. Or at least since Crisis on Infinite Earths #1.

That said, I don’t really care about whether it fails as a launchpad, jumping-on point, blockbuster, next chapter in the DCU, whatever. I just wonder if it succeeds as a Grant Morrison comic, because I don’t care about “The DCU” in the slightest, but I do care about the writing of Grant Morrison. And after that first read, I felt that I really didn’t have enough to go on. I did enjoy seeing Martian Manhunter get punked out, though. As I always say, kill ’em all. I also thought it was hilarious that Morrison was writing this mega-massive-major tentpole summer blockbuster comic the same way he wrote his weird opus Seven Soldiers–super-dense, chock full of elided dialogue and action, and necessitating multiple reads to make heads or tails of it.

Then I got a copy of it in the mail from DC, so I was actually able to sit down with it, re-read the whole thing, and flip around and re-read certain parts. And you know what? Now I kind of love this comic. It’s creepy, weird, totally jam-packed with ideas, paced in a very daring way for what’s supposed to be a popcorn comic (no big reveals, no shocking moments, no wish-fulfillment–compare it to the entertaining but comparatively straightforward “shocking season premiere” feel of Secret Invasion), it has a kind of nauseatingly blasé death for one of the DCU’s oldest mainstays, I love the Dark Side idea (Jack Kirby’s evil demigods falling to earth and taking human form), major plot points are conveyed simply through panel transitions and body language…I keep coming back to the Martian Manhunter’s death, which has more impact precisely BECAUSE it’s neither a big hero moment or a failed attempt at a big hero moment (“Not like this! NOT LIKE THIS!”). The pacing of it conveys the lack of regard for human life that these douchebag villains have. And certainly the shittiness of evil, as opposed to its grandiose awesomeness, has been a running theme of Morrison’s superhero work for a long time now.

Sometimes the art is rushed-looking–Superman looks like he’s stupid, and the table at which the Secret Society of Super-Villains parlay with mysterious asshole villain Libra changes sizes from panel to panel. But there’s a lot of great facial-expression stuff in there too, as in the Anthro vs. Vandal Savage fight, the confrontation between Boss Dark Side and Terrible Turpin, the Anti-Life kids…

Even the deadweight Monitors from Countdown seem like they have a weird society instead of just running around proclaiming shit like they used to. And who cares whether it ignores what happened to the New Gods in previous would-be event miniseries over the past year? Ignoring stuff you don’t care about is done every time a superhero writer working on a decades-old character hits a key on his laptop–so what if the thing he’s ignoring happened three months ago instead of in 1957? It’s a very good comic for me.

Comics Time: Kramers Ergot 4

June 2, 2008Kramers Ergot 4

Anders Nilsen, David Lasky & Frank M. Young, Renee French, Lauren Weinstein, Marc Bell, John Hankiewicz, Mat Brinkman, Ron Rege Jr, Sammy Harkham, Jim Drain, Ben Jones, Dave Kiersh, C.F., Stepan Gruber, Joe Grillo, Josh Simmons, David Heatley, Souther Salazar, Genevieve Castree, Allison Cole, Leif Goldberg, Tobias Schalken, Jeffrey Brown, Billy & Laura Grant, Jason T. Miles, Kenny, Andrew Brandou, writers/artists

Sammy Harkham, editor

Avodah Books, June 2003

Pre-order a fancy-sounding hardcover re-release from Amazon.com

For me at least it’s difficult to separate Kramers Ergot 4 from how it came into my life. The book made its debut at the first MoCCA festival, joining Craig Thompson’s Blankets in the “big giant powder-blue books that knocked everyone out” sweepstakes; all three events–Kramers, Blankets, and MoCCA itself–turned out to be milestones in my comics-reading life. In terms of Kramers, even for someone weaned on Highwater and NON such as myself, this was heady stuff. I seem to remember there being passionate, even angry debates on my then-stomping grounds of the Comics Journal message board over whether it should have “wasted” pages on non-comics content like collages, and then other debates about whether those non-comics pages are, in fact, comics. It all seems pretty meaningless now–I don’t even remember what side(s) I was on–but I suppose the point is that the book really introduced me to completely non-narrative comics, a strategy I don’t think I’d given much thought to until then. I feel as though in a very real way it introduced comics to non-narrative comics, at least by virtue of becoming the most high-profile and influential release of that nature to date in the then-young decade. If you look at that contributor list and compare it to people’s 2007 Best Of lists, you can probably see the power it had.

In my defense, it is a powerful book. I would say it is in fact a book designed to overwhelm, from the sheer size of the thing to its small-army contributor list to the “yes, but is it art?” nature of so many of its contents. I mean, the textless Mat Brinkman “monsters clash on the Rainbow Bridge” cover is a statement practically begs comparison to the great Hypgnosis album covers for Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd, even sharing a rainbow with The Dark Side of the Moon. Now that I think of it–and I promise I hadn’t, not even before my initial pass at this review–Dark Side is a great point of comparison in terms of how KE4 functions as a unit rather than as a collection of individual pieces. (There was little question in my mind as to whether I could approach talking about this anthology the same way I’ve done with MOME.)

See, one thing that struck me in giving the book a cover-to-cover read-through (the first time I’d ever done so) is that there are a surprising number of straightforward narrative strips given the book’s outré reputation. There are humor strips (Cole and Jones), autobio/slice of life (Brown), biography (Lasky & Young), underground-type sex’n’violence (Simmons), ruminative mythology-based storytelling of the kind that’s proven so popular (Nilsen), and just plain storytellin’ (Harkham). Even John Hankiewicz’s contribution has a discernible plot. Sure, they’re sprinkled throughout multimedia collages and Fort Thunder joy-of-markmaking exercises and multiple title pages and so on, but they’re there–sort of like how between the cut-up studio banter and looped analog samples and proto-ambient keyboards and psychedelic freak-outs, you can find unindictable masterpieces of rock-single construction like “Time,” “Money,” and “Us and Them” on Dark Side. Similarly, even these more easily graspable bits are, for the most part, pretty challenging in tone and content. Simmons’ contribution had me ready to put the goddamn book away the second he had a character take scissors to a puppy’s eye, Brown’s series of vignettes about dealing with the homeless, dangerous, or mentally ill is the most socially- and self-critical strip he’s ever done all at once, and Harkham and Nilsen’s contributions, “Poor Sailor” and a pair of Sisyphus strips, will no doubt make their creators’ all-time highlight reel. It’s kind of like creating a pop concept album about the pressures of late 20th-century capitalist society driving you insane until you die.

I’m not making this comparison because it’s cute. (I’m certainly not arguing that they sync up together, Wizard of Oz style.) I’m saying that Kramers Ergot 4 is put together the way it is on purpose, for the disorienting, overwhelming effect it has on the reader, how the narrative work lowers your guard for the nonnarrative, how the nonnarrative gooses your synapses and prepares you to focus on things you’re unaccustomed to focusing on in the narrative–how marks are arranged on the page, figures as symbols rather than as characters, design, the emotional impact of the strips rather than the plot-intellectual one. Instead of being a concept album, it’s a concept anthology. Hence the Dark Side comparison: In both cases there’s a sense of sprawl, of a thing you can’t possibly take in on the first pass and must return to and grab bits of meaning here and there, discovering new things each time. In both cases the material rewards repeat visits (I’m not sure I ever even read the Simmons strip before / I only figured out that the guy was saying “I certainly was in the right” a couple months ago). In both cases, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve grown to appreciate them more.

Comics Time: The Goon Vols. 0-2

May 30, 2008The Goon Vol. 0: Rough Stuff

Eric Powell, writer/artist

Dark Horse, April 2004

96 pages

$12.95

The Goon Vol. 1: Nothin’ But Misery

Eric Powell, writer/artist

Dark Horse, July 2003

136 pages

$15.95

The Goon Vol. 2: My Murderous Childhood (And Other Greivous Yarns)

Eric Powell, writer/artist

Dark Horse, May 2004

128 pages

$13.95

Originally written on July 26, 2004 for publication in The Comics Journal

‘Tis a strange fate that the breakout success story of Dark Horse’s recent attempt to craft a line of horror comics around its flagship title Hellboy turns out to be not so much Hellboy as Hellboy Junior. But such is The Goon, Eric Powell’s ongoing riot of hard-boiled noir tough guys, zombie splatstick, and Warren Comics pastiche. It’s unsurprising that its similarity to Mike Mignola’s endlessly fascinating tales of paranormal fisticuffs are both The Goon’s great strength and, by comparison, its great weakness.

The Goon takes place in what’s becoming a fairly common type of indie-genre-comic city, one that’s a melange of trash conventions thrown into a blender and poured onto the page. This one encompasses down-home hillbilly thugs, Edward G. Robinson-style gangsters, haunted houses of EC vintage, and so forth. (See also Street Angel‘s combination of mad scientists, b-boying ninjas, pirate conquistadors, and skateboarding female teen martial-arts experts.) The titular strongman (think Hellboy with a hat instead of horns, Sin City‘s Marv with a wifebeater instead of a trenchcoat, The Thing as a Tennessee redneck instead of a New York Jew) is the terror of the city’s underworld, serving as a brutal enforcer for the reclusive mob boss Labrazio. But a raging gang war against “the nameless man, the zombie priest” and his undead crime family has made the Goon and his Little Orphan Annie–eyed sidekick Frankie into the city’s unlikely saviors. As they’re all that stands between the city and uncontested zombie dominance, the Goon and his pal are forgiven their (ahem) enthusiasm for their work of roughing up lowlifes, werewolves, evil elves, giant fish people, et cetera, usually conducted with knives, Magnums, shotguns, huge monkeywrenches, talking chainsaws, et cetera.

Et cetera and ad nauseum, I’m afraid. Perhaps I’m simply armchair-editing the book, angling for it to become the type of genre fiction I personally enjoy, but the endless game of can-you-top-this splatter and silliness overpowers what could be a very interesting crime-horror concept. Now, I’m certainly not asking for the humor to be excised completely. There are moments that work hilariously–Frankie’s repeated “KNIFE IN YOUR EYE!” gag is in gloriously bad taste, and the reactions of the people of the Goon’s burned-out burg to his rampages are terrific in that “aieeeeeee!” sort of way. (“Look out!” says one bum in Volume One as the Goon gives the business to an arachnid poker cheat named (you guessed it) Spider. “He’s gone strangle crazy!”)

The problem is that when Powell gets serious, or seriously creepy, he’s clearly at his best. The Goon’s origin story, besides containing a pretty brilliant twist that alters our perception of his present-day behavior, packs a surprisingly emotional wallop. (I’m guessing Vito Andolini Corleone’s start in The Godfather Part II was the inspiration, and in this case the imitation is indeed flattering.) “What have I got to live for?” asks the Goon of his new friend Frankie as they embark on their first (and what seems at the time to be likely their last) gang-enforcer outing. At this point you’ve seen the Goon beat up, chewed up, and thrown up by nearly every monster known to man, and yet this clear-eyed (literally, for this panel only) expression of nihilism makes you feel the characters’ risk. Similar hints at a larger emotional tapestry are intriguing (a gorgeous dame whose romantic overtures the Goon thinks are too good to be true, the long and sordid history of the zombie priest), as is the fact that the hero of this story is himself a brutal criminal who looks good only in comparison to the cannibal zombies that fight with him for territory. Often these flashbacks are drawn in an evocative pencil-heavy style with far greater depth than the increasingly slick Saturday-morning cartoonisms that comprise the remainder of the series, to the flashbacks’ great benefit. But all this is inevitably drowned out by the next beheading, the next disemboweling, the next appearance of a spontaneously combusting orangutan. No, I didn’t make that last one up. Such is The Goon.

Comics Time: The ACME Novelty Library #18

May 28, 2008The ACME Novelty Library #18

Chris Ware, writer/artist

ACME Novelty Library/Drawn & Quarterly, December 2007

56 pages, hardcover

$17.95

Cruelly overlooked by many year-end best-of lists (my own included) due to its late-in-the-game arrival (now a perennial occurrence) and, perhaps, a level of quality we’ve come to take for granted, the latest installment of The ACME Novelty Library is a tough book to review by virtue of the fact that it belongs at or near the top of any such list worth a damn. In trying to express what is so compelling to me about Ware’s work in general or this book in particularly I am, to quote Stephen King on Clive Barker, almost literally tongue-tied. Instead I’m rambling on about year-end best-of lists, and eventually I’ll be enthusing vapidly. (Hey, it could be worse–I could be complaining about the people who find his work cold, emotionless, and boring. Specifically I could be calling those people morons. How lucky for you, then!)

In this particular case I’m kind of floored by how Ware assembles a panoply of snippets of a lonely young woman’s life–some are lengthy flashbacks, others are day-in-the-life moments, still others are seen from the perspective of the old building she lives in–into this sort of long seamless tapestry of ache. Like the tiny diagrammatic panels Ware foisted on an unsuspecting comics world, these narrative building blocks give the material an engaging ebb and flow, and simultaneously ape the way the protagonist’s own life flows without pause one dreary day into the next, occasionally enlivened by reverie or some small humiliation. Now that I think of it, she herself looks back on her life’s more exciting or rewarding times as dreams–temporary and illusory. And in a real way this book could go on forever, or at least as long as our heroine remains stuck in this (seemingly lifelong) rut, this cycle going on and on the same way some of Ware’s pages (the knockout front endpapers, for example) are all but cyclical. This chapter itself doesn’t really end, it just stops, which is perfect.

I don’t know, what should I say? He’s the best colorist, the best letterer? Those things are both true. His line is superhuman, like a machine made it, which is why people think it’s cold, but they’re wrong because he’s using that precision to nail specific and devastating emotions and sense-memories–my god, that moment where the heartbroken heroine sinks into her dormroom bed! “I lay there, facing the fake wood wall shelf…but it might as well have been the blackness of space…” The image has the pull of a black hole. And as it turns out Ware is also quite good at cartooning sex, particularly that delirious brand of first-flush collegiate sex, daily coupling and mutual masturbation and the raw, almost manic hunger to have and give and demonstrate pleasure. Cold schmold! All with the best chops in terms of line and layout of anyone in comics. The funny thing is I don’t really think of comics when I read this, I think of my life and my wife’s life and my friends’ lives and complete strangers’ lives, which of course is what makes it the very best kind of comics there is.

Comics Time: Nil: A Land Beyond Belief

May 26, 2008Nil: A Land Beyond Belief

James Turner, writer/artist

SLG, April 2005

236 pages

$12.95

When I was in middle school and first got into Monty Python, I assumed that most grown-ups knew all about philosophers, because Python had so many jokes about them. As it turns out the kinds of grown-ups who know all about philosophers first learn about them as kids in middle school who get into Monty Python, so it’s a bit of a self-perpetuating system. Anyway, Nil sort of takes this premise for granted–it’s like the looooooooooooooongest Monty Python philosopher sketch ever, with liberal doses of Brazil thrown in for good measure. Unfortunately it’s not funny, let alone as funny as Python or Gilliam solo. The basic idea is that there exists a dystopian land called Nil that embodies nihilism in its many conflicting forms, where people pilot big wrecking ships that destroy literal outgrowths of belief, and which is at war with a similar antithetical nation called Optima. The people of Nil spend almost all their time one-upping each other as to who best embodies the principles of nihilism, such as they are–except for our hero, Proun Nul, who yearns for something more. Or maybe he just yearns to have sex with the lovely Miss Void, I don’t know. The problem is that the concept never quite seems sure what it wants to be. Is Nilean nihilism a matter of literal, physical warfare against belief as a living thing, or is it the usual matter of debate and argument? If Nil is resolutely anti-capitalist, why is every page covered in ad parodies? If Nil is resolutely anti-totalitarian, why is it such an ersatz Oceania? Is it a model of efficiency, or of incompetence? Maybe some kind of point is being made here of the nonsensical nature of nihilism to begin with, but it feels more like an attempt to cram in every kind of joke available than a coherent choice of satire. It’s kind of baffling and it leaves the jokes without any solid ground to pivot off of, and it’s not as though any of the characters are developed in any sense but the most broad and parodic since they have no constants to play against. By the end of its 236 pages, which seemed a lot longer, I really didn’t care anymore. All told, the five or six minutes of total screen time given to the Nihilists in The Big Lebowski are a more effective satire of that anti-belief system and the excesses of the life of the mind in general.

All of this is compounded by Turner’s art, which is designy and iconic in the extreme. I’m sure there’s a perfect point of comparison out there that I’m totally missing, but what it calls to mind for me is flash animation, or some very old computer program, or Legos…it’s resolutely cold, flat, and artificial. This can occasionally lead to startling images–generally speaking, the bigger the weapon of war, apartment complex, or Nihilist temple, the cooler Turner makes it look through accrued geometric patterns. (Remember those flying bomb ships in Super Mario Bros. 3, with all the propellers and cannons and things? Kinda like that.) But for the most part it’s deliberately unlovely, making empathy or even awe impossible. It kind of substitutes cleverness for the usual kinds of qualities that make art compelling–of which cleverness is one, of course, but not the only one.

In some ways I think it’s exciting that a book like this can get made and published, but it wasn’t for me.

Comics Time: Thor: Ages of Thunder

May 23, 2008Thor: Ages of Thunder

Matt Fraction, writer

Patrick Zircher, Khari Evans, artists

Marvel, April 2008

36 pages

$3.99

A while ago I linked to a video of crudely animated Thors performing Slayer’s “Raining Blood” and, in a post that got some attention here and there around the Internet, said basically that Thor comics should be at least that metal. If your Thor comic doesn’t evoke Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant Song,” there is something wrong with your Thor comic. Needless to say, there’s been a lot wrong with a lot of Thor comics by that standard.

In Thor: Ages of Thunder, writer Matt Fraction takes a big step in the right direction. The action primarily consists of Thor attacking and beheading enormous frost giants, then dragging their heads into Asgard as trophies; between these feats he has sex. With the exception of the two included stories’ introductory pages, everything is done in big two-page spreads. There are shots of Thor’s war hammer Mjolnir dripping with gore. The chorus of the one Zeppelin song that explicitly references Thor, “No Quarter,” is paraphrased. The coming attraction page for the book’s sequel reveals its title to be Thor: Reign of Blood.

But in much the same way that it doesn’t quite get the “No Quarter” chorus right and didn’t quite name its follow-up after the Slayer album, it doesn’t quite gel overall. Mostly this is because of the narration captions in virtually every panel. It’s not that they’re knowingly overwrought–that’s as it should be–it’s just that there are way too many of them and there are way too many words in each. A action comic about gods warring with giants and constructed solely of two-page spreads should flow effortlessly, but the constant jibber-jabber stops both the eye and the brain short when they should be on cruise control. Show us how awesome your Thor is, don’t tell us. Moreover, I just happened to have read a whole lot of mythology-based comics recently, whether we’re talking about short stories in Mome or minicomics by Eleanor Davis and Matt Wiegle or flashbacks in Incredible Hercules, and the captions make this one feel comparatively belabored.

There’s also a disparity between the art in the two stories. Patrick Zircher’s detail-driven art packs genuine power, and the witty coloring by June Chung (dig the red noses she gives everyone–after all, it’s chilly in the realm of the Norse gods!) puts it over the top; Khari Evans’s figures, particularly his women, seem awkwardly proportioned and inconsistently constructed by comparison. (Though his Thor itself is quite strong, and he’s one of the first artists I’ve come across who truly conveys that Thor flies because he throws his hammer so hard the thing pulls him up off the ground with it.)

That being said, it’s all enormously more appropriate to a character based on gods worshipped by the priests who gave us the term “berserkers” than a leisurely rumination on the cyclical nature of existence set within the rural farms and diners of Oklahoma. It’s also entirely possible, perhaps even likely, that a collection of stories of this type (which is surely in the offing given the announced second issue) will make for a satisfyingly loud read, and be priced more efficiently to boot. In much the same way that I’m comforted that most kids’ first exposure to the potentially awesome character of Iron Man will be from Jon Favreau’s movie rather than Mark Millar and J. Michael Straczynski’s comics, I take great solace in the hope that somewhere, some kid is reading this while listening to the copy of Black Sabbath Volume 4 he stole from his older brother rather than reading something that will lead him to form the opinion that “Thor is boring.”

Comics Time: JLA Classified: Ultramarine Corps and Seven Soldiers of Victory Vols. 1-4

May 21, 2008JLA Classified: Ultramarine Corps and Seven Soldiers of Victory Vols. 1-4

Grant Morrison, writer

Ed McGuinness, J.H. Williams III, Cameron Stewart, Frazer Irving, Ryan Sook, Pasqual Ferry, Billy Dallas Patton, Freddie E. Williams II, Yanick Paquette, Doug Mahnke, artists

DC Comics, 2002-2007

JLA: 144 pages

Vols. 1 & 4: 224 pages

Vol. 2 & 3: 176 pages

$14.99

Buy Seven Soldiers from Amazon.com

Inspired by the delightful reading experience of working through the bulk of Grant Morrison’s recent, weird Batman run in one go, I decided to revisit his most ambitious project to date: The interlocking miniseries Klarion the Witch-Boy, Frankenstein, Zatanna, Mister Miracle, The Manhattan Guardian, The Bulleteer, Shining Knight, and Seven Soldiers—known collectively as Seven Soldiers of Victory. I started with the epic’s unofficial prequel, the three-issue JLA Classified miniseries Ultramarine Corps. In a way that earlier title is emblematic of all of Morrison’s output for DC. While nominally it revolves around a StormWatch/Authority-style take-no-prisoners super-team he introduced during his late-’90s JLA tenure and now updated for the Ultimates era, its villain is a revamped golden-age baddie (Nebula Man/Neb-U-Loh) who is now set up to be the ultimate weapon of eventual Seven Soldiers villains the Sheeda; themini also directly references characters and concepts (the Sheeda queen) that Morrison wouldn’t be using for another couple of years, and others that would pop up not just in Seven Soldiers but also in seemingly disconnected books like Batman (the Club of Heroes) and even the non-continuity All Star Superman (the Infant Universe of Qwewq). In other words–and this is fitting given Morrison’s view of spacetime as a single, physical living organism–what looks like a three-issue slushpile Justice League story is in fact simultaneously drawing from Morrison’s past, present, and future at the company. It’s all one big mega-story.

In this day and age of decodable genre entertainments, it’s tempting to spend this review of a re-read making connections and unearthing clues. I certainly did some of this during the re-read itself (one of my pet projects was pinpointing all four elemental golems mentioned by Baby Brain Stargard in the first Guardian issue.) It was also inevitable that I spent much of the re-read just blocking the plot out in my head in a more accurate way than I did the first time around. For example, I now think I have a pretty firm grasp on the exact roles played by the four main villains–Gloriana Tenebrae, Melmoth, Zachary Zor, and “Dark Side,” whereas if you’d asked me a couple days ago I’d have gotten the middle two conflated and had no idea how the first was connected to the fourth. Finally, given how directly the plot of the Mister Miracle mini–Darkseid’s forces win the eternal war of the New Gods and descend to Earth in the form of outwardly normal humans–mirrors what we’re told to expect from Morrison’s Final Crisis, it’s hard to resist trying to puzzle out where that mini fits in with the rest, or where the whole thing fits in with the flow of the DC Universe in general.

But I think the thing that I most want to convey about this re-read is just how affecting it is to read a superhero comic this dense. Everything I just talked about–the scattered Easter eggs, the continuity tweaks, the riot of opposing forces–are really just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the disparate elements the project comprises.In what almost seems like a self-satirical move, Morrison deliberately tapped an army of artists to illustrate the project (including one, J.H. Williams, who at various points draws in the style of every single other one) rather than allow this to happen through the vagaries of scheduling like it seems to do on all his projects. The effect is dizzying and sensuous, in no small part because this is the strongest set of collaborators he’s ever assembled, even given a hiccup in the production of Mister Miracle. Williams’ mimickry is a tour de force performance, Bianchi is a true otherworldly discovery, Sook and inker Mick Gray’s spotted blacks are sexy as heck, and Irving is a comic genius with color and facial expressions, just to name a few high points. Meanwhile Morrison himself discusses in his intro how he deliberately bounced between genres in the book, to encompass science fiction, fantasy, horror, action, comedy, soap opera, satire and more. So too does he vary up the raison d’etre of his “heroes”–none of them are in it as an exploration of What It Means To Be A Hero, which is an immediately disorienting difference from the norm as it recalibrates our expectations of what the characters will do at any given juncture. All in all it’s a bit like a supercompressed Twin Peaks or Lost–there’s just so much going on and the fun is in not knowing and trying to grok it anyway as you take succor in the crackerjack genre aspects.

The most pleasurable aspect of the project, ultimately, is that it is the challenge that the characters within face. It’s a huge story that’s just slightly too big for us to grasp from our frame of reference, but it gives off the sense that the picture is there to see if you know where and how to look at it–perhaps from the kind of vantage point that enables you to seed story points from a vast span of years into everything you write–rather than the nagging suspicion that the author has deliberately made vital information inaccessible. Trying to absorb and understand what’s going on is like standing on your tippy-toes to grab something on a top shelf, a delicious challenge to exceed your station just a bit and hold on to something outside your usual grasp, and if you don’t succeed this time, no big deal, there are any number of other angles you can come at it from. In that way the final page, one of my favorite endings to any comic ever, is a fittingly euphoric image: one of reaching.

Comics Time: How We Sleep

May 19, 2008How We Sleep

Eleanor Davis, writer/artist

self-published, February 2006

16 pages

price unremembered

Maybe the Little House shop will have copies available when it reopens in June

Created as a Valentine’s Day gift for her cartoonist husband Drew Weing, Eleanor Davis’s How We Sleep consists simply of 7 drawings of the two of them, and sometimes their cats, asleep in bed. It’s a remarkably sexy comic, and sweet too, succeeding because of the way those two qualities intertwine. Davis’s finely observed drawings of her and Weing’s undressed bodies convey intimacy about as well as you could hope for in illustrations, with their unidealized figures suggesting great mutual affection, attraction, and vulnerability. Their cats and their kind of goofy underwear remind us that these are just folks, albeit folks in love. This must have made a heckuva Valentine’s Day present.

Comics time: Never Ending Summer

May 16, 2008Never Ending Summer

Allison Cole, writer/artist

Alternative Comics, April 2004

96 pages

$11.95

Originally written on July 25, 2004 for publication in The Comics Journal

Never Ending Summer blazes no new trails. In fact, what trails it treads are familiar almost to the point of predictability: I think that by now we’ve all read enough auotbio comics to know that young, hip people drink cheap beer, complain about their jobs, obsess over their relationships, fetishize vinyl records, make mix tapes, and make out. If adolescent power fantasies are this medium’s overheated yin, post-adolescent disempowered realities such as this are its underheated yang.

But there’s a lot to be said for charm, and that’s why there’s a lot to be said for the very charming Never Ending Summer. The story, such as it is, follows author Allison Cole through a summer of minor upheavals in Providence, Rhode Island. Allison wakes up one day at the beginning of June with an enormous injury of an unspecified nature upon her lip. “So this is how summer begins,” she thinks as a friend drives her to the hospital in another friend’s borrowed car. It’s a fitting beginning to the story as it introduces several prominent themes: The power of Cole’s minimalist cartooning (her nightmare image of the injury consuming her entire face works perfectly), the unexpected difficulties that beset her throughout the season, and the support and succor she gains from her community of friends.

Cole’s debut graphic novel finds her confident in her use of her unique vocabulary of character, which is to say she draws adorable little people who look sort of like the ghosts from Pac-Man, but with arms and legs. Each is given a unique adornment for distinguishability–a ponytail here, an ironic moustache there, Descendents-style eyeglasses everywhere–and while that trick doesn’t always work, what does is the simultaneous sense of universality and idiosyncrasy the overall device lends to the characters and the story. It’s a lot harder to get tired of the misadventures of hipsters who hang out in kitschy dive bars when they look like stuffed animals. (It’s also interesting to compare this technique to the almost manic self-scrutiny of a Jeffrey Brown, say. Where Brown makes his seemingly uneventful autobio stories work through the intense navel-gazing reflected in his restless, sketchy inks, Cole takes the opposite tack and breaks the action down to a bare minimum of lines on a page. In the former, the reader is moved along by the sweaty work of the artist; in the latter, the artist encourages the reader to move the breezy work along.)

The clear influence overall is John Porcellino. Cole does not have the minicomics god’s assuredness of line, nor the ability to pull off the transcendental moments of liberation that marked Porcellino’s similar autobio novel Perfect Example. I was actually all the way through such a moment in Never Ending Summer before I realized, “hey, that was the big climax, wasn’t it?” But Cole’s learned that simplicity suits a simple story, There’s never a moment that feels forced, pretentious, or overblown, and the quiet moments are quiet without being maudlin or tedious. Some of my favorite images are simply Allison kneeling on her roof next to her chimney, or curled up with her cat. Clearly these are some of Cole’s favorite images, too.

Cole’s piece in Kramer’s Ergot 4 was a bit of inspired comedy, terrifically lampooning the oh-so-sensitivity of emo boys by casting them as the world’s wimpiest pirates; I’d have liked to see more of that wit in use here. I’m also not sure that the ending is earned by the events that come before: The idea is that Allison’s newfound creative outlet as a DJ enables her to be happy with and by herself rather than fixate on emotionally unavailable men, but wasn’t she already a cartoonist? Perhaps the nature of her cartooning–writing about her fixation on emotionally unavailable men–precludes that kind of fulfillment. Makin’ people boogie is probably a much better way to forget about that sort of thing. But unwittingly she’s done that here, crafting a delightful book that I’ll happily read again. It’s a promising start until she begins blazing trails of her own.

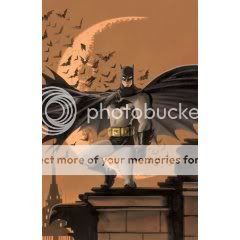

Comics Time: Batman #664-669, 672-675

May 14, 2008Batman #664-669, 672-675

Grant Morrison, writer

Andy Kubert, J.H. Williams III, Tony Daniel, Ryan Benjamin, artists

DC Comics, April 2007-April 2008 or so

22 pages each

$2.99 each

Grant Morrison is my favorite superhero comics writer, one of the very few writers in comics I’ll read anything by. Batman is my favorite superhero, the only character I feel an attachment to as an entity rather than as a character in a story that may or may not be good by artists and writers who may or may not be good. Put Morrison and Batman together and you should have a recipe for Sean T. Collins Nirvana, but for some reason that hasn’t been the case. What I seem to recall being the standard Kubert Bros.-related scheduling difficulties early on; Morrison working in a deliberately choppy, almost disjointed narrative style both within individual issues and from issue to issue and short arc to short arc; sketchy, sloppy art from Kubert and unremarkable ’90s-style art from Daniel and Benjamin jarringly interrupted by a bona-fide star turn from the great J.H. Williams III; that awkwardly inserted Ra’s al-Ghul-centric crossover with all the other Bat-titles; my job at Wizard coming to an end and with it my weekly free access to superhero comics…put it all together and you have a book tailor-made for me that I wasn’t even following.

I was recently loaned a more or less complete run of Morrison’s tenure on the title–sans the initial “Batman & Son” arc that introduced Batman and Talia al-Ghul’s enfant terrible son Damian and the issues pertaining to the Ra’s al-Ghul crossover in which the old villain attempts rebirth in the body of his grandson–and I was pleased to discover I liked the whole thing a lot.

Like so many of Morrison’s long runs it’s badly hampered by the art he’s saddled with, perhaps moreso here than in other cases since so much of Morrison’s staccato scripting depends on nuances of body language, facial expression, and mise en scène. Meanwhile, that pow-pow-pow pacing and those brief, three- or two- or even one-issue story arcs give the illusion of a lack of continuity within the run overall. But taken in one sitting these problems are easily smoothed over, and what reveals itself is a dual project.

First, and credit here goes to my friend Kiel Phegley for pointing this out, Morrison foregrounding Batman as the main point of interest in every story. Whereas normally the character plays a particularly badass brand of straightman to the more glamorous villains and horrifying murder-mysteries he’s up against, Morrison’s emphasis is on the hero himself, and on establishing him as every bit as weird, exciting, scary, and memorable as his antagonists. This is reflected in Morrison’s choice of antagonists itself: as with All Star Superman, he’s trotting out a parade of baddies who in one way or another serve as his flawed doppelgangers. The peak-human-specimen al-Ghul family, the crimefighting Batmen of Many Nations and their billionaire benefactor, three crazed Batman-impersonating policemen, even Bat-Mite–they all throw what makes Batman Batman into sharper relief via contrast, demonstrating that while he is indeed weird, exciting, scary, and memorable, he’s also a fundamentally good person who never loses sight of the values that matter to him and by which he’s chosen to define himself.

Second, Morrison is slowly advancing a novel and vastly more enjoyable take on the shopworn “shadowy villain manipulating things behind the scenes” mega-storyline in the person of the Black Glove, a figure of unknown provenance behind many of the story’s events. Morrison has basically avoided those annoying scenes where the shadowy figure literally appears as a figure in shadows once or twice per issue, making ominous statements and showing us just enough of his silhouette that we can start guessing whether he’s Mysterio or Hush or whoever. Instead, Batman arranges his recent cases into a pattern at the center of which is a hole in the shape of something that’s more of an idea rather than a person–a “king of crime” figure so brilliantly evil that even Batman had no idea he existed and had been pulling strings for nearly Batman’s entirely career. It’s all coming out in this kind of slow, unnerving fashion, more identifiable as something feeling weird about the stories rather than as a story element in and of itself. Hopefully the central revelation will be as satisfying as that of, say, New X-Men. At any rate, while I can see why people (myself included) may have gotten a bit lost in the shuffle, I’m now reading some of the book’s more oblique storytelling choices as just that–choices–rather than lapses, and I’m firmly back on board.

Comics Time: Boy’s Club

May 12, 2008Boy’s Club

Matt Furie, writer/artist

Teenage Dinosaur, 2006

40 pages

$5

This is one of the funniest comic books I’ve ever read. The closest thing I can compare it to is the music of the cock-mock-rock band Electric Six; both take the absolute lamest aspects of rokkin’-out culture–bad drugs, bad booze, bad food, bad jobs, bad taste–and po’-facedly present them like features of that lifestyle rather than bugs. Instead of phony rock gods, the main characters of Boy’s Club are a quartet of ’80s-style funny-animal cool dudes with all the right moves, like a cross between Bill & Ted, the Tri-Lams, and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Many of the funniest gags center on their cliché-heavy responses to absurd situations–lots of big grins and thumbs up, statements like “oh snap!” and “it’s a free country” and “peace out!”, words like “amigo” and “awesome,” and so on. Meanwhile, the visuals come across like a sitcom version of Paper Rad, frequently riffing on drug experiences to pull of non sequitur sight gags like one character’s face melting off or morphing into Falcor from The Neverending Story. The best jokes–and in this book, that means they’re pretty goddamn great–combine goofball visuals with that deadpan duuuude humor: a six-panel grid of reaction shots to a particularly huge hero sandwich, a character’s response to finding another character’s vomit in the bathroom sink. They’re kind of like Achewood if that strip were done by the guy your roommate bought pot from in college rather than a software designer. It’s the kind of comic you’ll stick in friends’ hands and force them to read it. If you like humor comics I really can’t recommend it highly enough.

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 10: Winter/Spring 2008

May 9, 2008Mome Vol. 10: Winter/Spring 2008

Al Columbia, Sophie Crumb, Dash Shaw, Ray Fenwick, Émile Bravo, Jim Woodring, Robert Goodin, John Hankiewicz, Tom Kaczynski, Jeremy Eaton, Kurt Wolfgang, Paul Hornschemeier, Tim Hensley, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds & Gary Groth, editors

Fantagraphics, December 2007

120 pages

$14.95

Mome Vol. 10 by contributor, in order of appearance:

* Al Columbia’s gorgeous and frightening front cover is so great that I found myself trying to justify the “someone’s about to torture an animal” back cover image, where normally I’d just say “fuck that shit.”

* I really like the ink and watercolor portrait that is Sophie Crumb’s first contribution to this volume. Her comics, though, are more of the smug writing and unpleasant art that have put me off of her work in past volumes.

* Dash Shaw’s science-fiction story is my favorite thing by him I’ve seen so far. I feel like his lo-fi diagrammatic art and layouts are really clicking here, while the storyline’s central conceit of a man who comes from a world where time runs backwards is ambitiously complex and demands Shaw be inventive in solving the problems it presents him with visually. The use of color is measured and smart, and there’s a weird pathos to both the ideas and the way Shaw draws the characters. I could imagine Kevin Huizenga doing a wicked cover version of this strip.

* Ray Fenwick does his sublime/ridiculous prose/subject matter juxtaposition thing again and I don’t think it works all that well here. Celebreality gossip culture is a soft target.

* Émile Bravo does another sociopolitical pictographical parodical morality play involving various ethnicities’ views of those below their rung in the social hierarchy; it’s a sensible idea but not something that blows you away with its insight, and I think he undercuts it slightly with the punchline.

* In the conclusion to Jim Woodring’s “The Lute String,” Pupshaw and Pushpaw are punished by the elephant god for their transgressions by being sent to Earth Prime! It’s as much fun looking at Woodring’s art as it is seeing this pair of pranksters get their comeuppance, and meanwhile it’s really odd and funny to see Woodring draw normal people. That punchline panel is a scream.

* I really like the way Robert Goodin draws people, with big forearms reminiscent of Popeye and really unique facial designs. I’ve seen world-culture myths adapted before, of course, and this Indian shaggy-dog story doesn’t stand out all that much in terms of the moral imparted or the mechanics of getting there, except for that lovely art.

* John Hankiewicz’s debut Mome contribution is a doozy. The narrated story, a tale of a gentrifying neighborhood reminiscent of Tom Kaczynski’s contribution to Vol. 9, draws attention to Hankiewicz’s finely detailed environments and thus heightens the frisson of seeing three very different types of figures moved through it by the cartoonist: a fairly realistic representation of the narrator and (I think) his father; a giant-headed, Tweedle-Dee/Tweedle-Dum-esque couple whose out-of-scale-ness represents the gaily crass nouveau riche new inhabitants of the neighborhood–in one memorable panel, they appear totally and disconcertingly naked; and a thickly delineated, faceless abstraction of a female, symbolyzing the anonymous self-mutilator whose weblog or livejournal the narrator habitually visits. It’s this strip I’ll return to, no doubt.

* I was going to say something like “Tom Kaczynski returns to the familiar territory of industrial/commercial environments altering people’s internal landscape,” and then I thought how funny it is that a subject like that is familiar territory for someone. I’m grateful that’s the case even though I don’t think it’s all quite cohered to the level of power he hopes for yet. This one comes close, but for some reason I think it would have worked better if it were longer and had more time to build up to the ending.

* Jeremy Eaton’s art is text-heavy and really loose, Stieg-esque I suppose. I’m not 100% sold on his short-story-ish tale of a retarded man accused of a gruesome crime, and I’m not sure the limited scope of his layouts gives his loose line enough room to breathe and really have an impact, but I’d like to see more.

* This is my favorite chapter of Kurt Wolfgang’s “Nothing Eve” so far. It’s replete with insightful observations about crowd dynamics, and a funny (if slightly overwritten) wink at how Hollywood inflects our view of how momentous occasions are supposed to unfold.

* Paul Hornschemeier’s heroine gives her one-night-stand the kiss-off in this installment of “Life with Mr. Dangerous,” and I think the scene plays realistically and uncomfortably. But Amy’s affect is so flat and her reasons for being such a downer all the time so underexplored that it seems to me like it’ll be really hard for her to hold our interest as a main character in an eventual collection of this story; I found myself agreeing with her gossipy coworker’s harsh assessment of her even while I thought the coworker herself was a bit too one-dimensionally glib.

* The punchline panel for Tim Hensley’s sole Wally Gropius strip this volume continues the disturbingly violent undercurrent he kicked off with the Jillian/incest strip last ish, and also serves as a rejoinder to the callous Columbia image that follows on the back cover.

* As is the case with pretty much every volume of Mome, it’s tough to imagine a better value for your alternative comics-buying dollar. The range in tone, style, subject matter, and even quality makes it a uniquely bracing quarterly(ish) view of the state of the art.

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 9: Fall 2007

May 7, 2008Mome Vol. 9: Fall 2007

Ray Fenwick, Tim Hensley, Al Columbia, Eleanor Davis, Jim Woodring, Gabrielle Bell, Andrice Arp, Joe Kimball, Mike Scheer, Tom Kaczynski, Brian Evenson & Zak Sally, Kurt Wolfgang, Paul Hornschemeier, Sophie Crumb, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds & Gary Groth, editors

Fantagraphics, October 2007

120 pages

$14.95

Mome Vol. 9 by contributor, in order of appearance:

* Ray Fenwick’s text-heavy pin-up pages, drawn on the dismembered back covers of old hardcover books, mostly do that ironic combination of grandiose language and quotidian concerns, but for my money his best gags are the simplest. His “FUCK YOU AND YOUR BLOG” page, where that line of text is juxtaposed with a jauntily floating balloon, is a little easy but still made me think of scanning it and posting it on message boards; the conclusion of his first piece, which states that your estranged former best friend is “not available for comment,” hit me like a punch in the gut.

* Tim Hensley’s Wally Gropius strips have always been both funny and interesting to me in their absurdist, angular deconstruction of old Archie visual and narrative tropes, but I think this is the volume where they really made me sit up and take notice. The panel to panel physical business in the library-based strip “Shh!” is a delight to behold, and the incestuous conclusion to “Jillian in ‘The Argument'” is a note-perfect, savage lampoon of Sam-and-Diane-style “enemies become lovers” rom-com rhythms.

* Al Columbia can draw like a motherfucker but that’s really the only thing I got out of his Hansel & Gretel pastiche. Aside from the kiddie-killer’s creepy face it wasn’t really funny or scary.

* Eleanor Davis’s tale of two brothers and the abandoned house they discover in the woods reads like a cross between her usual monster-myth beat and the observational-drama family matters of her minicomic Mattie & Dodi. I’d probably still prefer the straight-up former to a combination of the two. However, Davis’s ambiguous treatment of what the brothers experience in the house and the casual fraternal violence of its aftermath is certainly unsettling.

* The first half of Jim Woodring’s “The Lute String” is a bonanza of adorably mischievous drawings of Pupshaw and Pushpaw, weird fungal creatures and transformations that gently trigger a phobia I have about growths, and a portrait of what God looks like in the world of Frank. (He’s an elephant!) Woodring comics are funny and scary and beautiful and look like Woodring comics and nothing else, which is a colossal achievement.

* I don’t get why Gabrielle Bell spots blacks the way she does. It clutters the image and distracts from the rhythm of the page.

* Andrice Arp does her own thing with another adaptation of a pre-Revolutionary War anti-English broadside. What’s interesting about these is how astutely they simulate what comics probably would have looked like had comics proper been around at that time, not just in terms of the character designs and typography but the metaphorical visual vocabulary itself–a haughty English captain vomiting his heavily taxed tea down the throats of helpless colonists, for example.

* Joe Kimball’s vertiginous page layouts and masterful graytones maintain the eerie air of his previous contribution to the series, but the comparatively straightforward visuals and storyline–involving an old man returning to his vampiric lover for one last embrace–reveal limitations in his figurework and storytelling.

* Mike Scheer’s art is indeed astonishingly lush given that it was created in ballpoint pen, but beyond that I don’t connect with it. I like the overly long titles he gives each piece, though.

* Tom Kaczynksi’s vaguely Ballardian tale of a young couple traumatized by the construction of a high-rise condo in their ersatz neighborhood is another of his capitalist cautionary tales, and like the earlier ones it somehow never feels didactic despite the potential for lecturing or hectoring. I think it might be because he is primarily concerned with the emotional impact of consumer society rather than the political, philosophical, or economic impact. The narration is just shy of hard-boiled, which is funny, and placing his story right after one of Bell’s makes for an interesting contrast in terms of how the two artists differ in their depictions of urban ennui–Kaczynski is colder and sharper, and while his characters lack the warmth of Bell’s his pages convey their information more dynamically and convincingly.

* Zak Sally’s adaptation of horror writer Brian Evenson’s shifting-identity body-horror story “Dread” is a case of designy typography overwhelming whatever power the story itself might have had.

* At this point Kurt Wolfgang’s Bagge-esque cartooning is almost as out of place in Mome visually as Sophie Crumb, and it’s not the kind of style I gravitate to naturally, but the fact that his story’s premise is “last night before the end of the world” is a hell of a way to keep you eagerly coming back in anticipation of the climax. With my luck nothing will happen.

* This is the most effective chapter of Paul Hornschemeier’s “Life with Mr. Dangerous” so far, and not just because of the nudity–I just really liked the panel where our heroine’s murmur of “I’m sorry” to her absent boyfriend is partially drowned out by her one-night-stand’s snores.

* Sophie Crumb…I don’t see the appeal.

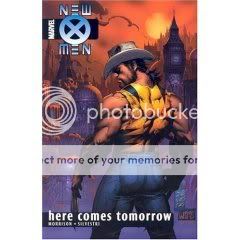

Comics Time: New X-Men Vol. 6: Planet X & New X-Men Vol. 7: Here Comes Tomorrow

May 5, 2008New X-Men Volume 6: Planet X

Grant Morrison, writer

Phil Jimenez, artist

Marvel, 2004

128 pages

$12.99

New X-Men Volume 7: Here Comes Tomorrow

Grant Morrison, writer

Marc Silvestri, artist

Marvel, 2004

112 pages

$10.99

Originally written on July 19, 2004 for publication in The Comics Journal

Grant Morrison is the X-Men franchise’s angel of mercy. In the two decades since Chris Claremont transformed a third-tier Stan’n’Jack creation into the most popular concept in North American comic books, no greater act of love has been committed on behalf of mutantkind than the truly mighty act of deadwood clearance that was Morrison’s much-heralded run on New X-Men. Culminating in the issues collected in the trade paperbacks Planet X and Here Comes Tomorrow, Morrison’s labor of love meant killing not just characters but concepts, entire ways of writing both the X-Men and superhero comics in general. The posturing villains, the alternate futures, the constant battles, the tortured soap operatics, even the costumes (easily the ugliest in all of superherodom, by the way)–for this potentially fascinating heroic-fantasy concept to be fascinating once again, Morrison says, we’ve got to wipe out everything they’ve come to be known for and start over. And it worked. Naturally, the House of Ideas undid nearly all of it within a month of Morrison’s departure.

Morrison refers to his four-year run on the title as one giant graphic novel; Planet X and Here Comes Tomorrow are the concluding chapters, and as such tie together nearly every loose end of theme and plot left dangling during his incredibly dense tenure. The big reveal that sets this final act in motion is the discovery that Xorn, the Chinese X-Man and healer with a star for a brain (!), is in actuality Magneto, the X-Men’s nemesis, presumed dead in an anti-mutant genocide that kicked off Morrison’s run. In the guise of the gentle Xorn, Magneto has exerted his influence over the Xavier Institute’s “special class” of ugly, poorly adjusted mutant teenagers, while simultaneously sowing the seeds of discontent and death among the X-Men themselves in the form of everything from extramarital affairs to widespread drug abuse. We’ve seen Magneto come back from the dead before, but we know we’re in uncharted territory when his first post-unmasking act is to quite literally destroy Manhattan. (This was sign number one that Marvel would be hitting the big red reset button once Morrison defected to DC. Where’s Spider-Man going to fight Doctor Octopus–Hoboken?)

Despite giving the preening bad guy his brightest moment in the sun, Morrison’s aim with Planet X is to savagely mock the character to the point where the last vestiges of appeal in his violent brand of sci-fi identity politics are erased. Magneto, who throughout the series had become a beloved martyr figure, his image appearing on the t-shirts and bedroom walls of disaffected mutant youths everywhere, quickly finds that he lacks the vision thing. His new “subjects” have seen him die and return so many times they don’t believe it’s actually him now. The special class, unwitting members of the new Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, either prefer Xorn outright or just think it’s kinda queer for their fearless leader to have dressed up in costume for months. In one hilarious sequence, the self-styled Master of Magnetism launches into a rousing speech so grandiosely Shakespearean that one can hear the mellifluous voice of Sir Ian McKellen proclaiming it in the next X-movie, only to be told by his henchman Toad that the masses can’t even hear him, seeing as they’re milling about in the street and he’s inside the upper floors of the Chrysler Building. Throughout this volume Morrison displays a genuine comedic gift, particularly in contrast to superhero writers whose idea of a gag is to have Ant Man crawl up his wife’s vagina. Morrison has said in interviews that his brutally satirical treatment of Magneto was a condemnatory reaction against the so-called nobility of a character who is nothing more than a murdering terrorist. It’s a welcome point of view even here in the real world, where we’ve so often been beseeched to “understand” the inexcusable, and where ostensible humanists serve as apologists for benighted fundamentalist slaughter.

Phil Jimenez, a solid if not thrilling artist of the George Pèrez school whose talent (besides drawing a fierce Jean Grey) lies in evoking superhero classicisms well enough to be able to subvert them too, draws Magneto throughout as an eight-foot-tall, floating, purple Darth Vader, but transforms his right-hand man Toad into the type of hip London scumbag who sells E outside of Sophisticats. Before long, the increasingly impotent potentate is addicted to Kick, the mutant club drug/performance enhancer. Bereft of new ideas, he begins dredging up idiotic schemes from X-books past, like reversing the world’s magnetic poles, a move as sure to kill mutants as it is to kill everyone else. By the time this pathetic old asshole finally gets his comeuppance (at the claws of Wolverine, naturally), his long-time rival Professor X has dismissed Magneto’s ossified, coercive philosophies utterly: “…the worst thing you ever did,” he tells the would-be dictator, “is come back.” Or as the stylish living weapon Fantomex puts it to the villain, “Is everything you say a cliché?” Adamantium claws may cut off your head, but having your self-created legend deflated really hurts.

Here Comes Tomorrow is to dystopian-future X-stories what Planet X was to Magneto stories: the final word. Readers of blockbuster superhero titles like Paul Jenkins’s Wolverine: Origin or Jeph Loeb’s Batman: Hush can tell you that while throwing a shock reveal into your story is easy, doing it in a way that’s supported at all by what’s come before, that’s both difficult to figure out before the reveal and impossible to miss afterwards, that enriches your understanding and enjoyment of what you’ve already read, and that generally doesn’t make you want to punch yourself in the face is apparently beyond the ken of most mainstream writers. Not so with Morrison, who after his surprise resurrection of Magneto in Planet X reveals a puppet master behind not just the once-again-dead magnetic supervillain but nearly every bad thing that went down in Morrison’s run and beyond. The “intelligent bacterial colony” known as Sublime was the very first form of life on Earth, and has labored for three billion years to stay at the top of the evolutionary ladder. The inherently powerful and fabulous mutants are the only true threat to Sublime’s self-confidence; he therefore worked behind the scenes in various guises to make sure that mutants were too busy getting killed by both humans and each other to realize their true potential for greatness. Here Comes Tomorrow takes place 150 years in the future, a time in which Sublime is preparing his final assault on the lifeforms of Earth by resurrecting the omnipotent and destructive Phoenix (aka Jean Grey), who was killed by Magneto in a final act of defiance just before his own execution.

If your eyes are already glossing over from simply reading a description of the hoary X-concepts being trotted out here, hang in there. (And ignore the fact that this arc marks the return to Marvel of early-90s superstar artist and Image co-founder Marc Silvestri. I’ve never been wild about the hyperrendered style of Silvestri, Jim Lee, and the like, but nor am I morally offended by it, as are some observers of the scene. There are a few storytelling lapses here–it would have been nice if the oft-mentioned White Hot Room in which the Phoenix resides was actually, y’know, white–but they’re mainly out of Silvestri’s hands. For what it’s worth, I think his style works rather beautifully here, cranking up the intentional superheroic/supervillainous clichés to eleven and giving this crazed, patchwork future a rough-hewn glamour and muscular sex appeal. His Wolverine, for instance, is both a man who is believably ready to die and a man with an unbelievable ass.)

What truly separates Morrison’s story from every other all-powerful-villain-in-a-future-we-may-be-too-late-to-prevent tale you’ve come across is not just his proficiency in generating stunning sci-fi concepts (the Termids, the Crawlers, the Feeders, the Phoenix Corps (!)) or instantly riveting characters (the Proud People (complete with Magic Car and Mer-Max the talking whale), Tom Skylark and Rover, Appollyon the Destroyer), though indeed introducing all of these in a four-issue arc whose world we’ll likely never see again is equivalent to throwing a gauntlet in the face of other writers of imaginative comic-book fiction. (See Morrison’s Seaguy for a similar act of “I’ll see you and raise.”) No, the strength of this book, and of Morrison’s entire tenure with the characters, is his belief that love trumps the horror of the world, and his ability to convey this in a way that’s emotionally direct without being trite or mawkish. It’s Dr. Hank “Beast” McCoy’s heartbreak over his own lies that gives Sublime an entrée, and Scott “Cyclops” Summers’ refusal to let go of a failed love with Jean Grey that ensures Sublime’s success; in the end, it’s connections that are just as personal–between ugly Ernst and disembodied Martha, between the identical triplet Stepford Cuckoos, between human Tom Skylark, his Sentinel parent Rover, and his robotic lover EVA, between the near-immortal Wolverine and his beloved Jean Grey–that set Sublime up for the fall. And it’s Jean Grey’s love for Cyclops, great enough for her to rewrite history and let him admit his own love for her one-time rival Emma Frost, that fixes “the hole at the heart of creation” and undoes Sublime’s machinations once and for all.

Morrison rode into New X-Men at the crest of a wave that saw Marvel taking bold risks with its core characters and ushering in a new writer-driven era of good, and even great, superhero comics; he rode out as persona non grata, his celestially vast ideas out of joint with a newly conservative company aiming mainly either to mimic the methods of blockbuster action cinema or mine fanboy nostalgia. He intended his forty-issue X-Men novel to be a gift to the franchise, but the gift has gone mainly unopened: Most of his new supporting cast has been shuffled offstage, the profoundly fresh relationship between Cyclops and Emma Frost seems poised for the chopping block, and eternal X-scribe Chris Claremont resurrected Magneto almost before Morrison had a chance to leave the building, pegging the villain’s whole Manhattan meltdown on the work of an impostor. (Would that we could place blame for the past twenty years of X-Men comics on a similar entity.) But we the readers are left with one of the most humanistic, richest, funnest, greatest superhero comics ever written. That’s gift enough.

Comics Time: DC Universe #0

May 2, 2008DC Universe #0

Grant Morrison, Geoff Johns, writers

George Pèrez, Doug Mahnke, Tony S. Daniel, Ivan Reis, Aaron Lopresti, Philip Tan, Ed Benes, Carlos Pacheco, JG Jones, artists

DC Comics, April 2008

32 pages

50 cents

Four of the six* ongoing DC-published superhero titles I read are written by Grant Morrison and Geoff Johns. The former is as engaging as ever in All Star Superman and Batman (which reads better in chunks than it does in monthly installments), while the latter has truly come into his own with Green Lantern and the Superman series Action Comics (both of which are at this point my all-time favorite main-line runs of their respective lead characters). Morrison, for his part, is my favorite superhero writer, and I enjoyed his earlier collaboration with Johns on 52. So despite having no interest in Countdown to Final Crisis and some innate resistance to the DC approach to crossovers–they tend to be epic discussions of comics-y concepts like continuity and multiverses, as opposed to Marvel’s tendency to root its events, however perfunctorily, in more familiar ideas like the privacy/security tradeoff or post-9/11 paranoia or whether the ends justify the means–I naturally gave this book a whirl based on my appreciation of its writers. I even brought home a copy since Jim Hanley’s was giving them away for free!

It’s a fun book. I don’t think I knew that it was going to be a collection of teases for upcoming storylines rather than a self-contained story, or even a coherent prologue to a larger story. But this approach seemed like a smart way to get across several things:

1) The DCU is heading in a unified direction…

2) …dictated by storylines involving the big iconic characters rather than Donna Troy and the Pied Piper…

3) …and written by Grant Morrison and Geoff Johns rather than Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray. Heck, given the reception of Countdown and its countless spinoffs, even Greg Rucka and Gail Simone, who are riding shotgun with vaguely connected tie-ins, seem like a huge deal.

DC Universe #0 seems to show that DC recognizes that its core characters/franchises (Batman, Superman, Green Lantern, perhaps Wonder Woman) are all pretty strong right now, so why not recalibrate the company’s crossover mojo around them rather than trying to force people to be interested in peripheral nonsense about nobodies? So instead of Monarch and Jason Todd, you get Batman grilling the ever-creepier Joker about a long-running plot thread involving a godlike supervillain gunning for the Dark Knight. You get one of Johns’s now-trademark multi-panel rapid-fire tastes of the rainbow of power rings now zipping around outer space. You get Superman in the future with the Legion of Super-Heroes (a concept I really don’t cotton to, but Johns has earned some credit in this department with his most recent Action arc), preparing to do battle with the hilarious fanboy-entitlement metaphor Superman-Prime. You get Wonder Woman’s godly forebears preparing to replace her with an army of 300 knockoffs, which makes for a funny visual at least. You get a creepy villain holding the scales of justice and trying to recruit other villains into yet another version of the Secret Society of Super-Villains, this one a Scientologyesque cult presumably dedicated to the awesome Jack Kirby villain Darkseid. You get an obliquely established return of Barry Allen, the long-dead Silver Age Flash, that plays itself out primarily through the shifting tone (and colors) of the narrative captions; it’s pretty funny to see Morrison do a mainstream-press-worthy character revival the same way he might establish an obscure plot point like, say, the link between the Undying Don and Ali-Ka-Zoom in Seven Soldiers. And you get the Spectre, but hey, they can’t all be winners.

As might already be apparent, the book is written in the crazy million-things-happening-at-once style of Morrison’s JLA Classified, Seven Soldiers, and those acid-flashback Batman issues from a few months ago, Johns’s Action Comics Annual and Sinestro Corps Special, and the pair’s 52. It’s possible to see the seams between the two writers’ work from time to time, but it takes some doing. I’m really happy to see Johns genuinely collaborating with Morrison and holding his own–it’s worth it for the horrified reaction of blogosphere snobs alone.