Posts Tagged ‘comics reviews’

Comics Time: Cold Heat #1

March 18, 2009Cold Heat #1

BJ and Frank Santoro, writers/artists

PictureBox, Inc., 2006

24 pages

$5

Read it for free at ColdHeatComics.com

Originally written on November 22, 2006 for publication in The Comics Journal

Cold Heat is a terrific comic for people who don’t think of their adolescence as having been particularly adolescent. That is to say, the prevailing approach toward reminiscing about one’s teenage years seems to be one of cringing embarrassment–no, actually, more one of condescension: “Ugh, what a little idiot I was then, I can’t believe I listened to Stone Temple Pilots,” etc. Writer-artists BJ (aka Ben Jones, he of those dog comics) and Frank Santoro say “fuck that noise” and instead choose to emphasize the rapturous beauty that adolescence’s grandiose melodrama and edge-of-disaster emotion constantly infuses into everyday life, particularly where music and romance are concerned. In doing so they craft a comic that is impossible not to compare to both arenas. Cold Heat‘s wispy, barely-there linework, the visual leitmotif of swirling and the rock-centric storyline–the events of the first issue revolve around our heroine Castle’s reaction to the fatal overdose of Joel Cannon, beloved lead singer of the noise band Chocolate Gun–don’t so much suggest as demand references to the blindingly happysad guitar maelstroms of Sonic Youth, My Bloody Valentine and M83. Moreover, readers of a certain age will no doubt remember the whirlwind of emotion they were caught up in upon the death of Kurt Cobain, the likely inspiration here. I still remember storming away from the dinner table when my dad dared to agree with Andy Rooney’s “good riddance” assessment of Kurt’s passing; Cold Heat is a little like remembering that incident in comic book form. But the romance angle is important too. The book starts out with an almost anti-romantic vignette–Castle is callously informed by the CEO of the company at which she is an intern that the outfit has gone belly-up after just having had sex with him. “I forgot my CD player there,” she realizes after she leaves–one more regret. But soon the wide-eyed, upturned-face beauty of Jones and Santoro’s portraiture of Castle takes hold, suggesting a lo-fi–or more accurately, doodled-during-math-class–approximation of romance-era John Romita Sr. The simplistic pink, white and blue color scheme adds to the “just hadda get it down on paper before study hall ended” feel so effectively that you might not notice the subtlety with which a sort of crayon shading is used to evoke smoke-filled, drug-addled parties and the lonely, scary darkness of suburban nightfall. And the hints of craziness–a murder mystery, a potential World War III, a minotaur carrying a severed head–somehow combine to evoke teenagedom much more accurately than a strict slice-of-life comic would. Add in the slick cover stock, a letters page (called “Heat Waves!”), a letter from editor Dan Nadel that reads like liner notes from that old Temple of the Dog CD you’ve been meaning to rip to your iTunes and a short prose story by Timothy Hodler about falling in love with the office superhero fan, and you’ve got a comic that feels like a cable from a world where the only thing that exists is a dimly lit bedroom in which you’re wearing ripped jeans and you just keep listening to and rewinding “Teen Age Riot” over and over again. Outstanding.

Comics Time: The Last Lonely Saturday

March 16, 2009

The Last Lonely Saturday

Jordan Crane, writer/artist

Red Ink, 2000

80 pages

$8, softcover or hardcover (!)

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Savage Critic(s).

Comics Time: Cold Heat #5/6

March 13, 2009Cold Heat #5/6

BJ & Frank Santoro, writers/artists

PictureBox, Inc.

48 pages

$20 (limited edition of 100 copies)

Cold Heat was truly tailor-made for my enjoyment. Combining genre storytelling with avant garde art and layout, minimalist linework with maximalist psychedelia, shoegazey atmosphere with cotton-candy colors with Kurt Cobain and Ziggy Stardust references with teen-angsty sex, drugs, and violence…basically, even if Cold Heat didn’t exist, it would be necessary for me to invent it. I never thought I’d get the chance to hold a new single issue of Cold Heat in my hands again, so on that level alone, the existence of this comic book (a double-issue, technically, but who’s counting) is cause for rejoicing, regardless of the execution.

Fortunately, the execution is killer. I think the standout story element in this installment is just how far Jones and Santoro are willing to take the Senator Wastmor character in terms of making him an embodiment of elite-political culture at its most loathsome, a sort of fever dream of naked cruelty, avarice, rapaciousness, and hypocrisy, complete with Uzis, orgies, and shitting on prisoners. It’s reminiscent of C.F.’s Powr Mastrs in terms of imagining Power and those who master it as corrupt, violent, and disgusting.

Visually, the changes here are subtle but important. The introduction of purples to the pink/blue color scheme to flesh out and darken the world a bit. The replacement of the swirling motif with one of diamond-like patterns imposes a new level and form of visual power on the world of the comic. “There’s no turning back” reads a Castle thought-caption at the bottom of a page where this geometric device is at its most prominent, and such is its impact that we absolutely believe her.

This is not to say that it’s all gruesome abuse and overwhelming visuals. Wastmor and his schemes and depredations are an over-the-top goof, at varying times referencing classic abuse-of-authority touchstones from Salo to Illuminatus! to Twin Peaks to Eyes Wide Shut to Revenge of the Nerds; he conducts his final Uzi-toting rampage clad only in thong underwear. Meanwhile there’s a laugh-out-loud dialogue exchange between Castle and her martial-arts instructor, in which they fill each other in on their respective adventures, that revels in the story’s deadplan implausibility in a fashion reminiscent of a similar recent scene in Lost. Like Scott Pilgrim on haphazardly mixed cold meds and anti-depressants, Cold Heat is a true trip, a visionary experience in a medium that should be providing them by the bucketload. Please read it.

Comics Time: Snake ‘n’ Bacon’s Cartoon Cabaret

March 11, 2009Snake ‘n’ Bacon’s Cartoon Cabaret

Michael Kupperman, writer/artist

Harper Entertainment, 2000

128 pages

$14

Hmm, what’s my “in” here? I could start by saying that Kupperman is a kindred spirit to Terry Gilliam: Gilliam’s animation work for Monty Python repurposed the imagery of Victorian and Edwardian England for surrealist humor and sexual satire, while Kupperman similarly works with visuals from the pulp and adventure publications of pre- and post-War America for surrealist humor (again) and riffs on the absurdity and violence of that culture. I could also say that he draws everything much, much better than he needs to–it’s like if Charles Burns did a book full of super-dense gag strips. I could point out that unlike most of the funnies, these comics truly work as comics, with visuals and text constantly trading off in terms of what’s doing the heavy lifting in getting the jokes across. I could elaborate by saying he’ll go both elaborate and direct with both components–for example, the visual gag at the heart of “Dead End Alley” is unanticipatable and complex, while the punchline panel of “The Cowboy in the Dinner Roll” is exactly what you think it’s gonna be and hammers the laff home with the subtlety of Mjolnir; meanwhile, you get text-heavy pieces like “Murder Makes My Head Hurt” and “From ‘Lives of the Cartoonists'” that take a full page to unspool and reach their pinnacle, but you also get instant-crackup juxtapositions like “Swamp Blanket Bingo,” “Sex Blimps,” “Sherlockules,” and “I Am a Gamera.” I could say that the work he’s doing in Tales Designed to Thrizzle, despite simply being a continuation of everything you’re seeing here, is better overall, but somehow that only makes this book more fun as it becomes rewarding to see how he refines his approach and execution in the later books. But I think I’ll call Michael Kupperman a comic (and comics) genius and leave it at that.

Comics Time: The Exterminators Vol. 1: Bug Brothers

March 9, 2009The Exterminators Vol. 1: Bug Brothers

Simon Oliver, writer

Tony Moore, artist

DC/Vertigo, 2006

128 pages

$9.99

Originally written on November 2, 2006 for publication in The Comics Journal

Conspiracy theory has long been the hallmark of a certain strain of DC-subimprint storytelling. From Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles to Warren Ellis’s Planetary, the edgier edges of Time Warner’s sequential art empire are rife with tales of beautiful badasses whose proficiency in matters of philosophy, style and killing people enable them to thwart the world’s secret chiefs and revel in knowledge withheld from the blissfully ignorant masses. The Exterminators is almost a willful antithesis to such books: Here, the people who unearth the true world order are an assortment of creepy working stiffs who kill bugs for a living.

If anything, first-time comics writer Simon Oliver actually goes overboard in serving up steaming piles of anti-glamour in this opening chapter of what augurs to be an apocalyptic conflict between humanity and an army of nature-run-amok creature-feature “smart roaches.” If Oliver had one Direct Market retailer order for every time one of his characters says “motherfucker,” he’d be well clear of the cancellation threshold. Meanwhile, the (self-conscious) sexiness of the Illuminatus!-inspired work delivered by his UK-based counterparts is transmogrified here into a sordid vibe that borders on misogyny whenever sexuality is broached. The archvillain of the piece is a lesbian corporate overlord who inducts new recruits (like lead character and ex-con Henry James’s restless girlfriend Laura) into her sinister enterprise by fucking them; future installments of the series introduce a new prostitute love interest for Henry who dresses up like famous literary figures for her johns, and an obese researcher who obliviously bangs a shady scientist who all but wears an “I’m a Fugitive Khmer Rouge War Criminal” T-shirt. Aside from the single angelic Hispanic mother whose horrific roach infestation serves as the central plot of this volume (and it’s not like that cliched character does much to ameliorate the other ones), women in The Exterminators haven’t yet proven to be a whole lot more than whores.

But based on this volume, I’m willing to give Oliver time to fix that problem. There’s something enormously refreshing about Henry, a character who genuinely enjoys the break he’s making from his criminal past and the hard but rewarding work he’s doing at the Bug-Bee-Gone company, run by his step-father Nils. Even as he’s slowly drawn into the mysteries of Egyptian bug gods, super-roaches and sci-fi biological weapons (developed by the corporation at which Laura is exploring her lipstick-lesbian side), he never cops a “look how cool I am” attitude nor a working class anti-hero pose–Oliver’s delightful scripting shows him attacking each problem like it’s a particularly frightening and yet potentially surmountable obstacle in a 9-to-5 job. He’s aided tremendously in this by the effortlessly pleasant cartooning of Tony Moore. His oblong faces and expressive eyes give each of his characters the kind of air that, were they real people, would make you come home from a day at work and say to your significant other, “You know such-and-such? Man, there’s just something about that guy I really like.” Moore broke out by helping to launch Robert Kirkman’s hit zombie epic The Walking Dead, and he’s just as proficient with horror-genre tropes here as he was there, from bug-ridden corpses to armies of the bugs themselves.

Overall Bug Brothers is skeevy fun, which is probably exactly what it set out to be, and the bargain price DC slapped it with will hopefully go a long way toward encouraging readers to pick up one of Vertigo’s most unique offerings. It’s not a series I want to see go legs-up anytime soon.

Comics Time: Ultimate Spider-Man #131

March 6, 2009Ultimate Spider-Man #131

Brian Michael Bendis, writer

Stuart Immonen, artist

Marvel, February 2009

32 pages

$2.99

The problems with Marvel’s Ultimate line were easy to spot from the start. Its appeal stemmed from its freshness: You didn’t need to be conversant with decades of continuity to understand it, you could get a thrill out of seeing familiar characters and concepts appear and behave in entertainingly new ways, and because the series were all brand new the writers could tie them to their cultural and political moment much more tightly than could writers of characters whose first appearances involved atomic testing or the Vietnam War. In all three cases, eventual obsolescence was, if not planned, then at least inherent: After a few years the books would develop convoluted continuity of their own, the novelty of the tweaks would wear off, the writers would run out of A-listers and start introducing lesser characters to dwindling returns, and the cultural and political environment would shift even as the characters would be stuck in corporate-superhero aging limbo. What’s more, and this was harder to anticipate, the mainline Marvel Universe would itself become Ultimatized, as Ultimate writers Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Millar were hired to apply their “realistic,” paramilitary spin on superheroes to the company’s flagship titles.

So it was inevitable that each of the Ultimate books would reach its sell-by date sooner or later. For me, Ultimate X-Men navigated strong runs by Millar, Bendis, and Brian K. Vaughan but was undone by a combination of Robert Kirkman’s “I Love the ’90s” nostalgia and a slow drift from depicting the characters, particularly Wolverine (who now looks exactly the same as his Marvel U. counterpart), as teenagers, which was part of what made it work. Ultimates lost steam in its second volume, which featured the introduction of magical antagonists in a way that didn’t jibe with the basic premise of the book and also suffered from writer Millar’s usual tics (self-impressed dialogue, lack of earned peripeteia). Ultimate Fantastic Four, originally a collaboration between Millar and Bendis, unimaginatively recast the FF as kids to no discernible benefit, then handed the reins to Warren Ellis for dreary and unscary reimaginings of their two best villains, Dr. Doom and (in spin-offs) “Gah Lak Tus.” The less said about miniseries like Ultimate Daredevil & Elektra, Ultimate Vision, and (remember this?) Ultimate Adventures, to say nothing of Loeb’s Ultimates 3, the better.

The one lasting highlight? Ultimate Spider-Man, Brian Bendis’s starmaking series and the line’s heart, if not its flagship (that would be Ultimates). Cooked up by Marvel’s then-President Bill Jemas as a reaction to a mainline Peter Parker who seemed hopelessly old and square (I think Jemas once compared him to late-period Billy Joel), the series stars a teen version of the Wall-Crawler and is the closest thing superhero comics have ever served up (completely unintentionally as best I can tell) to shonen manga. The length of its run (well over 100 issues at this point, a virtually singular accomplishment among non-creator owned superhero comics today), the big-eyed art of longtime penciller Mark Bagley, the age of its protagonists, and Bendis’s never less than deft combination of genuinely kick-ass superhero combat and intrigue with teen romance and angst all evoke Japan’s bread-and-butter boys’ adventure series. A brief slump in the upper-double-digit issues gave way to strong arcs wrapping up long-running storylines, while a recent, seamless transition from Bagley to Stuart Immonen gave the book a more polished look and a more faithful window into teen fashion and physical comportment. Of the four for-the-ages superhero titles that made me a Bendis believer and a regular superhero-comic reader in the early part of this decade–the others were Daredevil, since handed by Bendis and Alex Maleev to the equally capable Ed Brubaker and Michael Lark; Alias, the mature-readers super-private-eye collaboration with Michael Gaydos (starring best-new-female-character-in-years Jessica Jones), preemptively shuttered by Bendis, who subsequently picked up its plot threads in less satisfactory fashion in his mainstream-Marvel titles The Pulse and New Avengers; Powers, Bendis and Michael Avon Oeming’s creator-owned cops-and-capes procedural, hampered by erratic scheduling ever since its move from Image to Marvel’s Icon imprint–Ultimate Spider-Man is the only one still going strong.

So it pains me some to see it gamely playing along with Loeb’s reboot, which doesn’t seem like half the book USM is at its worst–but fortunately, the USM tie-in issues, of which this is one, are FAR from USM at its worst. Indeed, this is exactly how big event crossovers should be done. Bendis takes the simultaneously goofy and gruesome conceit at the heart of Loeb’s series–Magneto steals Thor’s hammer and uses it to drown Manhattan in a tsunami, killing millions–and treats it completely seriously, casting Spider-Man’s heroism against a genuinely traumatic and tragic backdrop. Bendis also takes the opportunity to shake up the supporting cast: Just before the flood hits, Aunt May is arrested under suspicion that she knows Spidey’s identity; during the flood, J. Jonah Jameson spots Spider-Man trying to help people while JJJ himself heads for the hills, and realizing everything he’d said about Spidey was bullshit, completely changes his tune; Spider-Woman, here interpreted as a clone of Peter, returns (presumably to take the reins after the reboot). Bendis makes great use of the definitive event trope–crossover appearances by other characters–by dodging the fight/team-up binary: Daredevil, who in the Ultimate Universe is kind of an asshole to Spider-Man, shows up but only as a dead body, a pretty traumatic thing for Peter to discover; the Hulk shows up too, alternating between his old-school childlike monster persona and the destructive weapon of mass destruction approach, which means you get both the classic Spidey-Hulk vibe you remember from your childhood and the raw terror of Spidey fleeing from his life from the Cloverfield monster in purple pants that the Ultimate Universe version of that relationship could be expected to provide. For his part, Immonen’s figurework is loose yet clearly thought-through–it’s very appealing, particularly his floppy, blocky hairstyles–and he has a knack for whacked-out visuals like J. Jonah Jameson’s picture windows revealing the fact that the Daily Planet building is almost totally underwater.

I have no idea where Ultimatum will leave Ultimate Spider-Man, and no particular desire to find out where it will leave the rest of the Ultimate line. But for now, it’s providing Bendis and Immonen an opportunity to do Spider-Man vs. the Apocalypse, and they’re seizing that opportunity with gusto. Good for them. I hope there are 131 more issues.

Comics Time: Dirtbags, Mallchicks & Motorbikes

March 4, 2009Dirtbags, Mallchicks & Motorbikes

Dave Kiersh, writer/artist

self-published, 2009

136 pages

$20 incl. shipping

Preview it at Kiersh’s website

Buy it exclusively from the author via Paypal – davekiershATaolDOTcom

I’ve kept my eye on Dave Kiersh’s work since coming across it in Jordan Crane’s seminal NON anthologies, where his simple line and design sensibility and poetic writing style coupled with his aching, romantic subject matter to suggest John Porcellino gone Young Romance. In the years that followed he’s drifted from more straightforward pseudo-autobio tone poems toward a more targeted examination of love, lust, and emotional turmoil among suburban adolescents, frequently filtered through the sensibilities of late ’70s and ’80s afterschool specials, young adult novels, and teen sex comedies. It’s an unusual pursuit, that’s for sure, and I think Tom Spurgeon said it’s a shallow pool for a cartoonist of Kiersh’s obvious talents to swim in, let alone spend a Xeric Grant on, but I don’t think Tom’s right. For whatever reason, that kind of material has a lot of power. The mirror it held up to the actual experience of suburban American adolescence may have simultaneously sensationalized and simplified that experience, but the reflection was recognizable nonetheless; artists as wide-ranging as Charles Burns, Judd Apatow, Richard Kelly, and M83’s Anthony Gonzalez have recorded their observations of that reflection, to memorable effect. Why not Kiersh?

Dirtbags, Mallchicks & Motorbikes, as you can probably guess from the title, sees Kiersh continuing to explore and refine his interpretation of the teenage-wasteland’s aesthetic and emotional milieux. It’s a collection of short stories, none of which feature any kind of resolution, not even the usual non-resolution resolutions you see in other short comics about young people and relationships; they just kind of end. It’s a bold choice, and it’s what prevents several of the more knowingly pastiche-driven stories–the boy who falls for his invalid mother’s sexy live-in nurse; the girl whose hotsy-totsy friend convinces her to shoplift a push-up bra–from feeling paint-by-numbers. Other well-worn types get zig when they should zag: The kid who winds up lonely in the crowd when he throws a party while his parents are away is the star quarterback; the beautiful tennis player with the loser admirer doesn’t slowly discover the man of her dreams beneath his grubby exterior, she simply fucks him in the stands just to see what life is like when you don’t care. The stories themselves twist and turn rewardingly before they expire; I was particularly taken with an interlude between the thoughtful quarterback and a drunk cheerleader who throws herself at him in the bathroom, which he escapes by promising to take a shower with her but climbing through the shower window before she can climb in with him, and by the way a story on teen pregnancy is constantly shifting the ground between the main character (the father-to-be) and everyone he encounters (the mother of his baby, his boss, his customer, his friend, his mother, the notional baby itself) in terms of values like responsibility and caring. Kiersh’s art is less fancifcul here than in his old work or his recent book Never Land, rooted firmly in emotions inspired by the everyday rather than daydreams. His thick round line is reminiscent of Keith Haring’s, particularly in the suburbiascape endpages, but Kiersh uses those chunky delineations to connote isolation rather than cohesion and community. This strikes me as very thoughtful, considered, personal work. If you like the Donnie Darko soundtrack school of wistfully emotional ’80s pop, or modern-day approximations thereof, I think you’ll get a lot out of this.

Comics Time: MOME Vol. 13: Winter 2009

March 2, 2009MOME Vol. 13: Winter 2009

Eric Reynolds, Gary Groth, editors

David Greenberger, Tim Hensley, Dash Shaw, Conor O’Keefe, Gilbert Shelton, Pic, Josh Simmons, T. Ott, Kurt Wolfgang, Nate Neal, Laura Park, Sara Edward-Corbett, Derek Van Gieson, Kaela Graham, Adam Grano, Henry Huntington, Casey Jarman, writers/artists

Fantagraphics, November 2008

120 pages

$14.99

Something about this volume of MOME makes it my least favorite in a while. It’s entirely possible that it just caught me on an off day, or that I’m all anthologied out. But while there’s always a tension in MOME between the best material it contains and the lesser stuff, and while that’s always been a big part of why I enjoy the series so much, I feel like we’re starting to see those two qualitative groups coalesce around two separate ways of doing comics. It’s almost like MOME is becoming two anthologies at once, and my problem with that is I’m not sure which one will win out in the end.

On the one hand, you have experimental takes on genre. In this volume, that school is represented by Dash Shaw’s dystopian science fiction, Tim Hensley’s continuing riff on Archie comics “Wally Gropius,” Derek Van Gieson’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark-type fable, a wordless journey into space with T. Ott, and Josh Simmons’s latest savage horror comic. It probably doesn’t surprise anyone that this is where my sympathies lie. Shaw’s “Satellite CMYK” comes first, telling the story of a Battlestar Galactica-esque satellite colony of survivors that has become so rigidly stratified that the mere existence of other levels of the structure is the subject of 1984-Brotherhood-style subversive conspiracies. Shaw conveys this idea by using a different color for each level. It’s not quite successful–the sameness of Shaw’s faces makes it harder to follow than it ought to be, and the power of the final reveal image is undercut by needless captions–but it’s as ambitious, imaginative, and emotionally rooted a bit of SF worldbuilding as any of Shaw’s work in this area. Hensley’s “Gropius” stuff continues to fascinate me with its angular character designs, kinetic non-action, and subtext of high-capitalist violence. (Riverdale this ain’t.) Van Gieson’s strip took me a couple reads to figure out that it was, in fact, a strip and not a series of discrete vignettes, but once I grokked what was going on, I really dug (no pun intended) that final graveside kicker, and the Gorey/L’Autrec/Alvin Schwartz watercolor visuals. Simmons, finally, can seemingly do no wrong anymore. I’m having a hard time coming up with any cartoonist whose work is as angry as Simmons’s has been lately. House, Jessica Farm, “Batman,” “Night of the Jibblers,” and this issue’s “Jesus Christ” (!) are breathtaking in their brutal nihilism–it’s horror that aims to punish, to tear down. In this case that’s literally the plot: a gigantic centaur-like Messiah descends from the heavens simply to wreak havoc on the tiny inhabitants of the endless city in which he lands. He’s too big for them to comprehend, physically or mentally, and their lives couldn’t matter less to him. It’s Lovecraft’s cosmic horror by way of the undergrounds’ hyper-detailed art (those buildings! that smoke! that bravura sequence when Jesus regurgitates a flaming sword!), taboo-shattering violence, and full-frontal nudity. Follow it with an equally bleak scratchboard science-fiction parable by Thomas Ott and you’ve got a heck of a one-two punch.

But then. The other pole is whimsy, and here’s where MOME loses me. This issue’s David B./Jim Woodring-style guest star is underground stalwart Gilbert Shelton, who serves up a limp, laughless story about his shitty recurring rock band Not Quite Dead being secretly sent by the government to overthrow the government of a banana republic. Sure, he draws the living shit out of it, but the whole thing feels so far past its sell-by date–a Grateful Dead spoof with jokes about hot-button cultural touchstones Elvis Presley and Madonna? Rock ‘n’ roll using its awesome power to subvert civil authority?–that it doesn’t make a difference. Underground-indebted MOME regular serves up a strange story about a folk singer named Minnie, drawn to look a lot like Phoebe Gloeckner’s similarly named stand-in character for no discernible reason; it’s a story about bein’ down n’ out and just wantin’ to play th’ blooz and it sucks that Greenwich Village is filled with yuppie scum now and blah, blah, blah. It’s nice-looking enough, but I don’t come away from it feeling or thinking anything new. Conor O’Keefe’s McKay-like figurework and Sara Edward-Corbett’s sharp Partyka-bred line (as well as her “Rabbithead”-indebted tiered narrative) cut through the ugly-cute clutter, as does Laura Park’s suite of strips about things she’s done at night (look at that quilt!), so it’s not as though the lighter/zanier material is completely undistinguished…I don’t know, I guess I just wasn’t in the mood. I definitely don’t know why we needed page after page of David Greenberger listing album titles according to the number of syllables they contain, you know? And that kind of decision makes me nervous for the future of the anthology.

Comics Time: Owly Vol. 5: Tiny Tales

February 27, 2009Owly Vol. 5: Tiny Tales

Andy Runton, writer/artist

Top Shelf, August 2008

144 pages

$10

This collection of Owly shorts features an eight-panel strip commissioned by Wizard for one of its periodical Wizard Edge indie-comics spotlight supplements back when I worked at the magazine. I remember being slightly amazed when it came in at how well Runton was able to boil down his usual themes–the need to be kind and share, obviously; more subtly, the notion that friendship, or just being a good person to others, frequently requires sacrifice, and that that’s not so bad; and just in terms of the visuals and basic set-ups, the interaction between “people” and nature–to a handful of panels. That’s the pleasure of this Owly book compared to the others: seeing Runton trot his characters and concepts through a succession of scenarios in short order. Maybe it’s just the presence of an appendix filled with early Owly sketches and a pair of the earliest Owly strips (in which Runton’s art is much more angular; the move to curvilinear forms was a smart one) that makes me think about the collection in this fashion, but it seems like practice would make perfect for a strip like this, and that’s what seeing one Owly story after another gives you the sense of–a talented craftsman riffing on a basic idea. The conclusions to several of the strips, like the one where Owly and Wormy meet a family of migrating geese out on a frozen pond, were so cute they made me chuckle and beam; the conclusion of another, about Owly and Wormy’s attempt to help a rabbit make a fancy flowerpot to replace the expensive one she’d gotten as a present for her grandpa but broken on the way to delivering it to him, was so sweet and unselfconsciously loving it actually made me tear up. Yep, that’s right: I laughed, I cried.

Comics Time: Owly Vol. 4: A Time to Be Brave

February 25, 2009Owly Vol. 4: A Time to Be Brave

Andy Runton, writer/artist

Top Shelf, December 2007

128 pages

$10

I’ve seen a bunch of critics say that the Owly books more or less defy review by adult critics, and perhaps even appreciation by adult readers. I’ve never really bought that, because I’ve always found Andy Runton’s line and character designs durable and warm, his use of rebus-like pictogram “dialogue” clever and engrossing, and his stories sweet and funny–that right there is good enough for this grown-up, even barring any other areas of interest. But in reading A Time to Be Brave–the plot: Owly’s friend Wormy believes a timid possum he encounters in the forest to be a dragon like the one he just read about in a storybook, while the possum believes Owly will eat him if he tries to join in on Owly & friends’ ballgame; emergency circumstances force everyone involved to put their fears aside–I realized that it actually does address two of my most grown-uppiest preoccupations in life and art. First, it’s about intellectually anthropomorphized animals, and through that lens it addresses issues of cruelty and predation that speak directly to some of my most deep-seated emotions and ideas on that score. Second, it’s about the need for people to intelligently, creatively cooperate in order to do the right thing, and the joy and satisfaction you get from doing so instead of falling back on competition, selfishness, and looking out for number one–a message I love seeing addressed here just as I did in, say, The Wire or Deadwood. So yes, it’s a great book for kids, but you’d have to pry it out of my hands first before you could give it to them.

Comics Time: Black Hole

February 23, 2009Black Hole

Charles Burns, writer/artist

Pantheon, 2005

368 pages

$18.95, softcover

Originally written on June 23, 2005 for publication in Giant Magazine.

COMICS TIME SPECIAL: For another, much more recent, and much more traditionally “Comics Time”-y review of Black Hole, read today’s inaugural edition of my “Favorites” series at The Savage Critic(s).

Load up your beer bong and break out your Black Sabbath LPs: You’re about to enter the gravitational maw of being a teenager in the 1970s. And as the title of Charles Burns’s epic graphic novel suggests, it’s deep, it’s dark and there’s no escape.

Black Hole was originally released in 12 installments that took over a decade to produce. “It was insanely fucking labor intensive to do,” Burns says. “Each drawing was really designed and layered and labored over.” As a result, it nails the sights and sounds of being young, dumb and full of cum as well as any coming-of-age comic ever has–but with a skin-crawling sci-fi twist.

Black Hole‘s deeply creepy journey into the Seattle suburbs’ heart of darkness stars Chris, a stunning “popular girl,” and Keith, Chris’s secretly lovestruck lab partner. Amid the dead-on period details (you can practically hear Harvest and Aladdin Sane playing as you read) and gut-wrenching depictions of the high-school caste system, Burns sets loose a sexually transmitted disease that grotesquely mutates its teen sufferers. Chris and Keith catch the bug and are drawn into a community of plague-victim outcasts in the woods outside of town, where amid the Halloween-mask faces, lizard tails and extra orifices, someone’s begun killing the kids off.

Teen angst and teen horror may be familiar territory, but Burns’ genius lies in colliding these two subgenres in an explosion of drugs, sex, hallucinations and murder. It’s all transmitted through Burns’ nightmarishly vivid artwork, which is as close to immersing yourself in a blacklight poster as you can get without the use of a Schedule I controlled substance. Simply put, you’ve never seen a comic like this before.

Darkly funny, steamily erotic and scary as hell–you know, like junior year–Black Hole owns its genre(s) more than any other comic has since Watchmen dissected superheroes 20 years ago. Read it, and like the first time you listened to Led Zeppelin IV, you’ll know you’ve got a masterpiece on your hands. A+

Comics Time: The Awake Field

February 20, 2009The Awake Field

Ron Regé, Jr., writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, April 2006

48 pages

$7.95

Originally written on July 23, 2006 for publication in The Comics Journal

Everything is magical to Ron Regé, Jr. This is his greatest strength as a cartoonist. His trademark line, equally weighted throughout the page and shot through with exclamatory dashes that radiate outward from nearly every character (even inanimate objects, in many cases), gives his work a vibrant, vibratory glow. Each page becomes a miniature epiphany, or at the very least an enjoyable semi-psychedelic experience, like an Ambien hallucination. Over the past few years Regé has employed this singular style to varying effect; its greatest exponent is his graphic novel Skibber Bee-Bye, wherein Regé uses it to elevate and enhance at first whimsy and then horror to almost rhapsodic levels. But in works like Yeast Hoist #11 (centering on a slideshow-esque series of depictions of Regé sleeping in other people’s apartments during a road trip) or Regé’s mini-comic contribution to McSweeney’s #13 (a painfully credulous account of a failed suicide bomber), it’s as though the power of his art enables Regé to coast, taking for granted that we too will see the beauty in all things, be they boring or bestial. In other words, everything is magical to Ron Regé, Jr., and this is his greatest weakness as a cartoonist as well.

Thankfully, it’s the strength that comes through in The Awake Field. And boy, does it ever. This slim, slick volume (I love its bendable, laminated cover) is perhaps the best argument yet for why Regé belongs at the forefront of the form. There’s the format, for starters: You’d have to turn to one of Kevin Huizenga’s Or Else issues to find a one-man anthology comic this exquisitely structured, with each strip or vignette leading perfectly to the next like a concept album. Right from the opening chapter, in which a series of bird’s-eye-view splash pages draw us through an open bedroom window to soar alongside a family of glowing spritelike beings through an explosion of vegetation and stony architecture beyond, Regé makes clear that his interest is in drawing you in and pushing you along. A handful of collaborations with his bandmate-slash-babymama Becky Stark, especially the perfectly touching “The Hazard Rocks” (adapted from a children’s poem by Stark called “The Stranger and the Mouse”) imbue the book with the hermetically-sealed, world-of-two joy that lovers who are truly on the same wavelength can produce. This blend of romance and mania is also present in “Finding Privacy in the Hypnotist’s Ballroom,” a rapturous “dance routine presented as 8 cartoon panels” that contains an unexpected belly laugh (a stand-alone shot of the dancer’s boyfriend standing there immobile after the dancer throws a towel on his head) and an homage to Magritte’s “Les Amants” (much less ambiguous in tone, of course).

The book draws to a close with a crescendoingly wordy succession of strips and panels centering on Regé and Stark’s belief in the imminent “invention” of peace on Earth. It’s genuinely moving–not because their recipe, involving as it does phrases like “impulses of consciousness in an infinite field of light,” stands much of a chance of success, but because for the duration of this comic Regé gives you a glimpse of what such a world looks like to him. It is, indeed, magical.

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 4: Spring/Summer 2006

February 18, 2009Mome Vol. 4: Spring/Summer 2006

Eric Reynolds & Gary Groth, editors

David B., R. Kikuo Johnson, Jeffrey Brown, Martin Cendreda, Sophie Crumb, Jonathan Bennett, Paul Hornschemeier, Gabrielle Bell, Anders Nilsen, David Heatley, John Pham, Kurt Wolfgang, writers/artists

Fantagraphics, 2006

136 pages

$14.95

Originally written on July 23, 2006 for publication in The Comics Journal

I wouldn’t want Mome to be any better than it is. See, it’s taken me until the anthology’s fourth installment to realize this, but a goodly sized chunk of its appeal lies in the uneven quality of its contributors. One of the series’ stated goals was to provide readers with a venue in which they could watch a fixed assortment of young cartoonists grow and develop, the implication being that in Mome we could stack up a given creator’s contributions against themselves and see what works and what doesn’t. Maybe it should have been obvious to me–maybe it was to you–but equally inherent in the project’s set-up is the chance it affords us to stack up a given creator’s contributions against another’s. Pitting the great against the deeply so-so in a regularly scheduled cage match is an excellent way to teach readers what does and doesn’t make for good comics–to separate, in other words, a David B. from a Sophie C.

Let’s start with the latter end of the spectrum, then. It’s not that Sophie Crumb’s comics have nothing to recommend them, necessarily; they do have a free-spirited, effortlessly vulgar energy that’s rare in the higher echelons of altcomix these days (though not nearly so much if you step away from the big-name tables at an SPX or MoCCA and sniff through the equally undistinguished punk-rawk comics being churned out by kidz at a Kinko’s near you). It’s just that that’s really all they have. In “Be a Bum,” Crumb rails against the self-obsessed autobio stereotype–in fact, her cri de Coeur of “Don’t spend 10 pages going on and on about taking out the fukin’ garbage!” can only be interpreted as a potshot against fellow Mome contributor Jonathan Bennet, whose previous three offerings have followed a Bennett-esque protagonist as he took photographs, fed pigeons, and (yes) went through someone’s garbage respectively, and whose contribution to Vol. 4, “I Remember Crowning…” replaced the Bennett figure with a bald middle-aged guy but still reads like a parody of indie navel-gazing, the kind of strawman a guy like Scott Kurtz would construct when he gets upset that he can’t follow Jimmy Corrigan. But Crumb lacks the very rudimentary self-awareness necessary to realize that her own endless stories of gutterpunk slumming are just as solipsistic and bereft of larger meaning. Indeed, she touts her own superiority: “I’m too busy having an interesting life, and I don’t take enough time to write and draw!! I am not a bored suburbian loser! My life is so weird and crazy, I wouldn’t know where to start!!” My goodness, how did this salt-of-the-earth wild-woman got to the head of the altcomix class without any external privileges whatsoever? I couldn’t hazard a guess! The pot-kettle comparison is worsened in another of the strips in this volume, where she outdoes Bennett’s most quotidian contributions by recounting a pillow-talk conversation with her boyfriend and a bout of flatulence experienced by their dog. And in her “Smone Bean the Premature Teen,” which can’t seem to decide if it’s a lampoon of America’s sexualization of tweens or a gross-out incest gag comic, she doesn’t even accurately quote Kelis’s “Milkshake”! It’s maddeningly lackadaisical work, right down to the okay art–say what you will about Bennett, but at least that cat can draw.

But a slick line is no guarantor of success, and if Bennett is exhibit A, then Paul Hornshemeier can close the case. His ongoing “Life with Mr. Dangerous,” serialized throughout Mome’s volumes, is as beautifully rendered as any of his work, all bulbous curves and soft corners filled with the kind of perfect, muted colors that’ll land you a consolation-prize Eisner nomination. But. The. Story. Goes. Nowhere. Since it’s about a young woman whose life appears to be going nowhere, maybe that’s the point, but when you tackle a boring situation by creating boring art, the whole is not always greater than the sum of its parts. Martin Cendreda takes an opposite tact: He peppers his “La Brea Woman,” which chronicles a divorced father’s run-of-the-mill day with his young son, with captions imbuing every minor character they meet along the way with a meaning-laden backstory. This doesn’t work either. “Five years from now,” reads the box above the check-out woman at the grocery store, “Valeria’s only son is killed in Iraq.” Groan. (The moonlit concluding shot of the elephant replica is nice, though.) Somewhere in between is Gabrielle Bell, whose examination of a young woman’s lifelong love for a favorite band contains some perceptive moments (“Once I would’ve liked them. Once they would’ve made me cringe. Now I liked them again,” she says of one group) but overall displays the same static figure work and flat-affect tone that’s always left me cold on her comics. In Mome’s realist camp, it’s only R. Kikuo Johnson’s dazzling display of illustrative proficiency (and Louis Riel fandom), “John James Audubon in Pursuit of the Golden Eagle,” that makes an impact, as much from cannily eschewing lit-fic in favor of historical comics and examining man’s relationship with animals (something I’m noticing comics seem to do well) as from the power of the visuals (goddamn).

In the end it’s the surrealists who win the day. They’re led by the great David Heatley, whose lo-fi figure work is perfectly suited to the violent and sexual non sequiturs of the dream comics he contributes; I found myself wishing he didn’t say they were dream comics, though, as the disclaimer undercuts the power of the imagery. Anders Nilsen chips in a photograph-and-comic installation that, he says, served as a sort of rough draft for his graphic novel Dogs & Water, and it’s as alarmingly good as everything I’ve read from him. As with most of his comics, you don’t necessarily know what this collection of blurry landscapes and cut-and-pasted cartoons is about, but you can almost instantly grok what they’re about–I certainly challenge you not to feel a little more lonely and hopeless after reading it than you did before, whether or not you can make heads or tails of it. Somewhat less effective in its randomness is John Pham’s “221 Sycamore Ave.,” another ongoing story being serialized in the anthology. The dreams of its protagonists–a bitter old teacher and his housemate, a ghost of some sort–take the story on a turn for the weird, and while the sharp, blocky shapes that dominate the dream (an underground-manga feel can be detected) provide a memorable contrast with the rest of the tale, the cumulative effect of the two halves is a bit uncertain. More tonally assured is the philosophical horror-comic contribution of Jeffrey Brown, yet another of his hugely rewarding explorations of territory beyond his usual autobio and humor beats. Juxtaposing a Godzilla attack with thought captions like “Everyone is anonymous at the end of things” could be an exercise in irony in other hands, but a few small strokes of Brown’s thick, minimalist inks make it work as they evoke accumulated human endeavor swept away by sudden, thoughtless violence.

Violence is also at the heart of “The Veiled Prophet,” this issue’s contribution from David B. His gifts as a cartoonist and storyteller are so varied and subtle that reading his work is almost an unconscious process. One moment, you’re reading an historical account of an Arab religious cult; the next–without a single seam you can point to and say “right there, that’s where the change took place” you’re reading a horrific fairy tale about tsunami-like armies of corpses and a man whose face no one can look at and live. Throughout, insights into human nature–the link between religious fervor, tyranny, and sexual mania; the sinking feeling that defeat at the hands of such forces is inevitable–shine through like a searing peak through the prophet’s veil. B. doesn’t so much draw as weave–threading together spears, skeletons, strands of cloth, naked bodies to create panels whose indelibility as stand-alone images (nearly any one of them could have been isolated for the volume’s cover) is actually surpassed by their cumulative effect.

Basically, the guy is a genius.

Which is part of why putting B. in the anthology always seemed an odd choice. Not only is he older and from a different linguistic background than most of the other contributors, but he’s also so freaking good that putting him amongst up-and-comers (even the really good ones) feels almost like bullying. But perhaps the message sent by his membership in Mome is an important one: Whatever the qualitative differences between a David B. and a Sophie Crumb might be, they are both doing the same thing–making comics. With that in mind, both readers and the creators themselves have every right to demand that the work of the latter class live up to that of the former.

Comics Time: Sulk Vol. 2: Deadly Awesome

February 16, 2009Sulk #2: Deadly Awesome

Jeffrey Brown, writer/artist

Top Shelf, December 2008

96 pages

$10

The first thing you have to do when you read Jeffrey Brown’s all-MMA issue of his new one-man anthology title is disabuse yourself of any preconceptions the phrase “86-page fight scene” may engender. I myself was picturing a lengthy Frank Milleresque wordless slobberknocker, a showcase of action choreography. Brown had other ideas, particularly on the “wordless” score: Nearly every panel of the three-round bout between the veteran thinking-man’s-fighter Haruki Rabasaku and the charismatic bruiser Eldark Garprub is captioned or ballooned with a breakdown of their thoughts, moves, or both. Instead of dazzling us with pyrotechnics–the closest he ends up getting to that is with the very idea of the book itself–Brown uses the constant narrative jibberjabber to a) impress us with his devotee’s understanding of MMA, and b) slow time to a crawl, making each round feel like an hour’s worth of battle to the combatants. It’s an interesting move that dovetails with the story’s occasionally ruminative feel, particularly the abrupt, downbeat ending and the sensitive treatment of the two fighters’ slightly cheesy but nevertheless sincerely articulated worldviews. Now that I think of it, the vibe given off is akin to arthouse wire-fu flicks like House of Flying Daggers, not with that level of beauty of course, but in the way physical combat is treated as something both impressive and sad.

Comics Time: Sulk Vol. 1: Bighead & Friends

February 13, 2009Sulk Vol. 1: Bighead & Friends

Jeffrey Brown, writer/artist

Top Shelf, September 2008

64 pages

$7

For all its lo-fi provenance, Jeffrey Brown’s art has always felt rounded and tactile and full to me. His figures may have the disproportionately large heads and bendy arms of doodled cartoons, but they move around in environments you feel like you could swing through the panel into and explore; seeing one of his gridlike pages is like being presented with an array of tiny windows that way. Meanwhile there’s an emphasis on shading that reinforces the palpability of what he’s drawing. There really isn’t anything else, including (or perhaps especially) all the young cartoonists you see upon whom Brown is an obvious influence, that looks like it. It works a lot differently than, say, David Heatley’s stuff, despite the surface similarities you’d find between two guys who do lo-fi autobio comics with lots of little panels.

Bighead isn’t autobio, there aren’t a lot of little panels, and it’s only barely lo-fi, but all of the above still stands. In the past, this kind of parody work is the closest Brown has come to really showing off his chops, and that trend continues. All those penstroke shading lines frequently accrue into something rather lovely–the robotic arms of the Claw’s deathtrap, the darkness of “one of Chicago’s famous ‘indie rock’ shows,” the vortext that swallows the Author when he messes with reality a little too much.

Meanwhile the superhero parody gags made me laugh repeatedly, particularly the dialogue. Brown really nails overwrought, superhero house-style banter that makes it seem like its author doesn’t quite understand how to write. “This time you’ve gone too far, The Claw!” “I’m crazy? I’m crazy?! Don’t you know who you’re talking to? You’re talking to me!” There are equally effective sight gags, from the Superboy-like Little Bighead getting so emotional about the Pacifier’s rampage that he finally just breaks down and starts sucking on the vigilante’s rubber-nipple headgear to the opening splash page of Bighead crashing through a window with a caption reading “HOLY SHIT!” And then there’s the tragic tale of Beefy Hipster, driven to supercrime by his inability to fit into his favorite band’s American Peril t-shirts.

It’s a funny, intelligently drawn superhero humor comic, and usually you can only get one or the other, if anything, so if you want to laugh at superhero comics that actually are intriguing to look at, by all means check this out.

Comics Time: Scott Pilgrim Vol. 5: Scott Pilgrim vs. the Universe

February 11, 2009Scott Pilgrim Vol. 5: Scott Pilgrim vs. the Universe

Bryan Lee O’Malley, writer/artist

Oni Press, February 2009

192 pages

$11.95

The greatest trick Scott Pilgrim ever pulled was convincing you its conscience didn’t exist. For a long time, the series’ skeptics criticized the shortcomings of the characters as though their existence was a shortcoming of their creator–as though writer/artist O’Malley was unaware that Scott was kind of shiftless and feckless, or that Ramona Flowers was a little bit cruel and aloof, or that their group of friends was cliquey and catty. I definitely see where such critics are coming from, for a couple of reasons: first, that was pretty much my line of attack when I first read Jaime Hernandez’s Locas material (newsflash: Hopey’s a jerk and Maggie’s a mess!); second, I am now a 30-year-old married homeowner in Levittown, and the further I get from Scott’s situation, the harder it gets to relate to, or even in some ways really care about, his plight.

But over the past three volumes, O’Malley has slowly pulled back the operating curtain to reveal the beating heart of the series; if you’ll allow me to mix metaphors, what this means is that the chickens have been coming home to roost. It turns out that all those evil ex-boyfriends aren’t just plot devices, but people who’ve had a lasting effect on how Ramona lives. It turns out that Scott’s glibness both hurts his relationship(s) and enables him to see their potential when others can no longer do so. It turns out that Knives’s lasting crush on Scott isn’t just a funny recurring gag, but something that’s screwing up her life and causing her to screw up the lives of those around her. It turns out that all the “we suck”isms the band indulges in actually have power in a self-fulfilling prophecy kind of way. It turns out that supporting players have lives of their own and that they can really grow to dislike how oblivious the main characters are to that fact. And so on and so forth.

At the risk of saying what I say any time a new Scott Pilgrim comes out, the singular achievement of the series is conveying all this stuff through the visual language of video games, action comics, and shonen manga. By all means, let the evil ex-boyfriends whose attack finally splits up Scott and Ramona be Japanese hipster versions of Tomax and Xamot, the creepy Crimson Twins from G.I. Joe. Let the fact that Scott is going to have a very rough time in this volume be foreshadowed by not collecting any loot when he defeats a tiny robot at a party. Let the whole emotional tone of the book be telegraphed in a pair of anecdotes about ’80s Chris Claremont X-Men storylines. Let trying to figure out Ramona’s big secret be represented by having her inexplicably glow every once in a while–and then let that be conveyed in part through having a foil cover!

I’m not trying to make the case that Scott Pilgrim fleshes out its characters or connects emotionally the way a good Clowes or Burns or Tomine graphic novel about young people trying to form and maintain relationships does, or that addressing such people is completely unprecedented. It doesn’t and it obviously isn’t. It’s still as much or more about screwball comedy and banter and clever visual elements as all that. But it’s a really fun book, and a lovely-looking book, and ultimately, surprisingly, a complex book. Pretty sneaky, Scott.

Comics Time: Cry Yourself to Sleep

February 9, 2009Cry Yourself to Sleep

Jeremy Tinder, writer/artist

Top Shelf Productions, 2006

88 pages

$7

Originally written on July 23, 2006 for publication in The Comics Journal

Try to contain your surprise: This book from Top Shelf contains cute, anthropomorphized animals! Gee, I hope you were sitting down. Ah, I kid because I love, of course. And while it is true that Top Shelf has returned to that Chunky Rice sweet spot many a time since Craig Thompson knocked one out of the park with it years ago, Jeremy Tinder’s Cry Yourself to Sleep distinguishes itself by, well, distinguishing itself. It doesn’t go in for the cute-overload of a Spiral-Bound, nor for the tremulous quasi-mysticism of a Pulpatoon Pilgrimage (the AdHouse Books effort that of all post-Chunky “Manimals’ Search for Meaning” books feels most like a Craig Thompson cover band). It mainly sets out to be funny, and quite happily, it succeeds.

It’s a slight volume with a slight plot: Over the course of a couple of days, three pretty much adorable characters intended as stand-ins for the book’s twentysomething target audience–a guy named Andy, a rabbit named Jim, and a robot named The Robot–struggle with three early-life crises–Andy’s novel is rejected by a publisher, Jim gets fired from his job, and The Robot realizes he’s a soulless jerk. A pair of pages in which three successive, nearly identical panels tie each of the characters’ stories together bookend the book. But to his credit, Tinder’s emphasis is not on setting up an overly neat ‘n’ sweet parallel structure, but on the comedic potential of how the individual stories ramble their way to their respective conclusions. Andy’s story in particular is peppered with amusing digressions: an interlude in which a little kid sports a fake handlebar moustache in an ill-fated attempt to browse the adult section in the video store where Andy works, another in which Andy’s friend Nate (who happens to be a little bear who wears glasses) advises him to spice up his novel by inserting a completely unrelated misadventure experienced by Nate’s menopausal mom. Sure, both scenes have that “well, this is my first graphic novel, and these are really funny, so I’m getting them in there come hell or high water” feeling to them–especially the menopause story, which is pitched to Andy for precisely that reason–but Tinder pulls it off with keen pacing and exceptional cartooning (his character designs are easily the strongest funny-animal work being done in this vein today–check out poor hot-flashing Joan Bear’s furrowed brow and preposterous hair). The fact that his jokes are actually funny is obviously key. Unemployed rabbit Jim gets the best of them when he’s fired from his job at a sandwich shop for getting fur in the subs, complains that the latex gloves he’s supposed to wear don’t fit him because he doesn’t have fingers, then gets reprimanded by his (human) father for “play[ing] the species card.” The Robot’s got some rock-solid moments as well. His entire quest to become as free as a (literal) bird reads like a good-natured roast of such alternative comics tropes, and in the lachrymose sequence that gives the book its title, you’ll notice that there’s no tears to be found on his metal face–robots can’t cry, duh. An occasional hint of mawkishness creeps may creep through now and then (that by-the-numbers romantic subplot at Andy’s video store, for example), but overall the saccharine level is refreshingly low. The goal of Cry is simple: to make you smile. Mission accomplished.

Comics Time: McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern #13

February 6, 2009McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern #13

Dave Eggers, series editor

Chris Ware, guest editor

Chris Ware, Gary Panter, E.D. Muenchow, Ivan Brunetti, Charles Burns, David Heatley, Seth, R. Crumb, Daniel Clowes, Rodolphe Topffer, John McClenan, Bud Fisher, Milt Gross, Louis Beidermann, Kaz, Mark Newgarden, Jim Woodring, Archer Prewitt, Lynda Barry, Charles Schulz, George Herriman, Philip Guston, Mark Beyer, Richard Sala, Art Spiegelman, Kim Deitch, Joe Sacco, David Collier, Chester Brown, Ben Katchor, Richard McGuire, Jeffrey Brown, Julie Doucet, Joe Matt, Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, Adrian Tomine, David Heatley, Ron Rege Jr., John Porcellino, writers/artists

Ira Glass, Chris Ware, John Updike, Charles M. Schwab, F.W. Seward Jr., Tim Samuelson, Glen David Gold, Michael Chabon, Chip Kidd, writers

McSweeney’s Quarterly, 2004

The other day I said that most of the big hardcover comics anthologies put out by prose publishers over the past few years draw from a “comics as high art” canon consisting of classic newspaper strips, the undergrounds, RAW, people who were published by Fantagraphics or Drawn & Quarterly during the ’90s, and Kramers Ergot. Turns out I really nailed it when it comes to McSweeney’s #13: I could be wrong, and correct me if I am, but after taking a closer look at this one I’m pretty sure that every single cartoonist in the book falls into one of those categories. What’s more, it pares away the wilder edges: The only underground guys you’ll find here are the three most high-falutin’, R. Crumb, Kim Deitch, and Art Spiegelman; the Kramers contributors–the ones that aren’t covered in any of the other categories, that is–are lo-fi autobio guys like Jeffrey Brown and David Heatley, while (depending how you count one of Ron Rege’s most straightforward and topical comics ever) the whole Providence school of noisecomix is nowhere to be found.

In other words, editor Chris Ware is presenting a very, very specific, and familiar, vision of alternative/art/literary comics here. There’s the emphasis on artifact and ephemera, with reproductions of a hand colored copy of a Rodolphe Topffer bootleg and bizarre old-timey “comics are good for the sould” advertorials, while sketches or unfinished strips from George Herriman and Charles Schulz presented as their contributions to the book. There’s the prominent masturbation humor placed toward the beginning and end of the book so you really can’t miss it. There’s the de rigeur current-events strip or three. There’s the ever-present link to mortifying memories of lonely childhoods in which superhero comics serve as both instigator and mitigator of misery–witness basically all the guest text pieces, particularly those of Chip Kidd and Glen David Gold. There’s the plethora of strips about how loveless and thankless and pointless is the life of the artist/thinking man/aesthete in general and the cartoonist in particular. When certain critics trot out their anti-altcomix hobbyhorses, this book is almost certainly the sort of thing that makes them whip those suckers into a gallop.

There are plenty of reasons not to give a damn about that, mind you. Ware, of course, is a genius, and his taste is as respectable and enjoyable as you’d imagine, if a bit narrow. He has a terrific eye for excerpts: the surreal ending of the otherwise realistic passage from Black Hole he includes must be absolutely stunning to people who’ve never seen it in context, for example, while the chapter he takes from Louis Riel, featuring the execution of a loudmouthed Anglo prisoner, would most likely close out Chester Brown’s highlight reel. In both cases a particular skill of the artist is emphasized: With Charles Burns, it’s how his inks can subtly shift between sensualism and horror; with Brown, it’s his knack for staging, in this case displayed by how the prisoner’s censored rantings take on an almost physical presence that absolutely overwhelms the staid characters at which it is directed. Then there’s the novel way he handles Los Bros Hernandez, intercutting two unrelated stories by Gilbert and Jaime in order to approximate the experience of reading them in their two (and sometimes three) man anthology series. I think Gilbert’s material (the devastating, temporally jumping “Julio’s Day”) comes off the stronger, but that of course is also one of the pleasures of reading Los Bros.

And that’s not all. While not quite the knockout blows listed above, the material from artists like Joe Sacco, Adrian Tomine, Dan Clowes, and Ware himself are also quite strong. Unexpected contributions from John Updike and Philip Guston are roped in. The early section on newspaper strips cleverly arranges contributions from Mark Newgarden, Ivan Brunetti, Clowes, Ware, Crumb, Seth, Kaz and more right up against Mutt and Jeff and the like, making an implicit argument that the strip format holds as much potential as the more traditional graphic-novel or short-story modes. Meanwhile, it’s always edifying to read Gary Panter or Mark Beyer, and one of the great comforts of all these big anthologies is that I know I’m never more than 100 or so pages away from some Ben Katchor. Entertainingly, the packaging, as it were, may be the best and most innovative part of the book. Strong minicomics by Ron Rege Jr. and John Porcellino are tucked into the folds of a massive, and massively impressive, cover by Ware. The competing takes on “the history of comics” presented on the front of the cover by Ware, the inside of the cover by Panter, and the endpapers by Brunetti are dazzling, while reproducing images from a 1936 “How to Cartoon” guide by E.D. Muenchow was inspired.

Now, there are the same old problems any anthology has, too. This is likely just a YMMV issue, but the predilection of many anthologizers to place material from Seth and Joe Matt back-to-back merely reminds me that I’ve never much cared for either; Matt’s subject matter is usually dull and offensive, while for some reason I’ve just never felt comfortable with how Seth’s thick, wavy lines sit on the page. I’ve yet to be sold on Lynda Barry or Richard Sala either. And not all of Ware’s selections are as perfect as the ones listed above: Richard McGuire’s “ctrl” is lovely to look at, but he handled the subject matter with tons more nuance and sensitivity in “Home”; and just once I’d like to see Ivan Brunetti represented by stuff from Haw! And as far as Ware’s editorial presence is concerned, he sometimes lets his enthusiasm get the better of him, as you can see in his text pieces, which are heavy on hyperbolic assertion: “Charlie Brown was a real personality, living on the newspaper page—he wasn’t a picture of someone, he was the thing itself…”; “Philip Guston is the first painter, ever, to truly paint a portrait from the inside out.” If he was a blogger writing about Final Crisis, other bloggers would be writing about how ridiculous he sounds.

But those last few concerns are all pretty minor in the face of a book full of, let’s face it, really good comics by really good creators. I mean, there are only four contributors I don’t care for or something like that, right? What’s to complain about? Well, it’s a lack of imagination, that’s what. And I’m as surprised as anyone to here me say that about an effort from Chris freaking Ware. But while there are standout moments to be found here—the cleverly constructed cover materials, the creative editorial layouts of the strip material and the Hernandez Brothers’ stuff, the Burns and Brown selection—the primary sensation engendered by reading McSweeney’s #13 is “yep, that’s exactly what I expected.” And that’s a real bummer in a way, isn’t it? Leading with a bunch of strips about how dull and pathetic it is to be an artist, then segueing into a Crumb strip called “The Unbearable Tediousness of Being” just to hammer the point home; sprinkling it with guest appearances from prominent prose writers who can’t shake the melancholy of their six-year-old selves dressing up in towels and underwear and pretending to be Batman; closing with a Brunetti strip about how Kierkegaard intentionally sabotaged his own love life, then died alone, segueing into those adorable “history of cartooning” endpages also by Brunetti, so that what you’ve just read in the Kierkegaard strip calls into question any pleasure you might get from Brunetti’s laser-precision pastiches of Superman, Eustace Tilly, Mr. Peanut, Enid Coleslaw, Fred Flinstone et al…I dunno, is this what comics is? Obviously it is to Ware, and the chances are good it is to a decent chunk of the McSweeney’s audience, so maybe this is exactly what they wanted to see. It’s just not what I wanted to see, and probably not what I would have chosen to show, either.

Comics Time: In the Flesh: Stories

February 4, 2009In the Flesh: Stories

Koren Shadmi, writer/artist

Villard Books, February 2009

148 pages

$14.95

I learned something about myself from reading this book, and that is that my phobic reaction to animal cruelty isn’t really, or isn’t just, a phobia. There’s a story in here in which one of Shadmi’s many languid, slightly pillowy, sexy brunettes sensuously recounts how she and a childhood crush tortured a cat to death. The second I realized where the story was going I had my usual reaction of needing to look away, needing to put the book down. This time I forced myself to keep reading, and you know what I discovered? Fury, a heart-pouding fury I was frightened to discover in myself. I don’t like what it says about me that it’s in there.

Anyway, the cat-killing is a pretty small part of the book. That story, and all of the rest of them, is really about sex. And Shadmi’s art works fine for that purpose. He’s primarily a magazine illustrator–his work here looks familiar enough that I must have seen quite a lot of his work elsewhere–and his elegant line and gently curving bodies are reminiscent of such animator-cartoonists as Robert Goodin and Cyril Pedrosa. (Oddly, there’s a panel that seems like almost a straight rip from Dash Shaw’s Love Eats Brains, but that’s about all he owes to anyone doing “ugly” work.) As I alluded to above, there’s a certain sameness to his dark-haired, pale-irised, fleshy femme fatales, but that’s an appealing template, admittedly. He pays a lot of attention to backgrounds, which is welcome.

The problem is the subject matter. Basically, the sexual hang-ups of twentysomethings have already been handled by the cream of the altcomix crop, and Shadmi just isn’t up to snuff. When he goes in a surreal direction, he’s up against (say) Dan Clowes, and Shadmi’s visual and narrative metaphors are comparatively facile. A couple spend their first date and sexual encounter with bags on their heads, and everything goes great until the guy takes his bag off and says something that isn’t to the lady’s liking, and then she says this was a mistake so he puts his bag back on. You know? There’s a lot where that came from, and frankly, you got to do better. Even the less fanciful, more slice-of-lifey stuff seems easy-peasy and undergraduate compared to, for example, Adrian Tomine’s angry work on the same subject. Expand the age group of the characters when looking for points of comparison and you end up bumping against Black Hole or I Never Liked You…

I don’t know, I guess what I’m saying is that while the SVA-trained visuals are immediately impressive, the stories are doughy enough to leave me surprised that this is a debut from a major book publisher. It’s fine enough work, I don’t begrudge its existence, as minicomics they’d be the belle of SPX, but it’s not there yet. And I don’t mean to belabor the business with the cat–my basic opinion on the work had already been formed by the time I got to that story–but you’ve got a lot of work ahead of you if you’re gonna draw a sexy lady talking about torturing a cat to death and make it something other than a cheap shot.

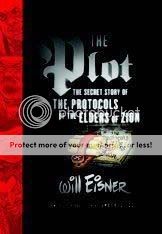

Comics Time: The Plot: The Secret Story of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

February 2, 2009The Plot: The Secret Story of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

Will Eisner, writer/artist

W.W. Norton, 2005

160 pages, hardcover

$23.95

Buy it in paperback from Amazon.com

Originally written on February 20th, 2005 for publication by The Comics Journal

This is a sad book. Sad not simply for the passing of its author mere months before its publication, nor for the tragic legacy of hatred it depicts, but rather for the confluence of the two: One of the greatest cartoonists in history felt compelled by circumstance to spend the last years of his long and illustrious life chronicling, in The Plot and its revisionist-Dickensian predecessor Fagin the Jew, vicious calumnies against his ethnicity and religion, slanders and lies that by now should have been exposed, renounced and ridiculed out of public discourse for good.

But we’re meeting the new boss now, and he looks familiar. When an English prince feels perfectly comfortable attending a costume party in Nazi drag (and moreover when none of his friends appear to find this objectionable); when the nomenclature of Hitlerism is routinely, provocatively, deliberately (and often exclusively) applied to the descendents of its victims (as when paleocon talking head Pat Buchanan used a thinly veiled Anglicization of “ein volk, ein reich, ein Fuhrer” to lay the blame for the second Iraq war on “Israel, Sharon, Likud”; to say nothing of “Zionazi” and “Jeningrad”); when the progressive magazine AdBusters points out the Jews in a list of influential neoconservatives (they were denoted with dots rather than tiny Stars of David; thank heaven for small favors); when former CIA agent Michael Scheuer, author of the well-received anti-administration tome Imperial Hubris alleges that Americans’ support for Israel is the result of “probably the most successful covert action program in the history of man,” and suggests that the Holocaust Museum is being used to guilt the United States into support for the Jewish state as part of this program; when the state-run media and state-approved clerics of American “allies” from Egypt to Saudi Arabia routinely recycle the hoariest blood-libel horror stories; when the University of Bielefeld polls Germans to find that over 60% of them are “sick of” hearing about the Holocaust–one can understand Eisner’s preoccupation.

For as The Plot demonstrates, anti-Semitism rarely shows its face without hiding behind a nominally political mask. The real and (far more often) imagined crimes of the neocons or Israel are simply the latest societal safety valve for Jew-hatred: the White Russians saw Jews behind the Bolsheviks, the Communists saw Jews behind the capitalists, the capitalists saw Jews behind the Communists, the fascists saw Jews behind Versailles, the Klan saw Jews behind the blacks, and on and on and on. The irrational belief in the nigh-mystically conspiratorial character of Jews throughout history–a belief that found its most infamous articulation in the fraudulent handbook of Jewish world domination, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion–is always finding new venues for expression. That legitimate criticism of, say, Israeli intransigence or neocon utopianism and overreach gets caught and drowned in its undertow is simply another of its disastrous consequences.

The fungible nature of the Jewish Conspiracy’s particulars is shown from the start by Eisner, who spends a sizeable portion of the book detailing the origins of The Protocols in an anti-Napoleon III tract by writer Maurice Joly. Joly is depicted as a three-time loser, constantly in trouble with the French authorities and all the more assured of his words’ power because of it. In an effort to cloak his criticism of the Emperor, he took what he believed to be Napoleon III’s cynical, might-makes-right viewpoints into the mouth of Machiavelli and published them in a book entitled The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu. It’s a rather gross misreading of Old Nick (one of the few political philosophers in history worth a damn), and it certainly doesn’t fool the government, which imprisons him. His trial contains one of the finer images in the book: Joly, eyes aflame with righteousness, refusing to admit the book is an attack on the Emperor. It’s a more effective image by far than the one on the subsequent page, where in Eisner’s trademark pantomime style Joly proclaims, one hand on heart and the other aloft, “IF THE READER SEES A RELATIONSHIP TO THE INFAMY OF THE EMPEROR, AM I TO BLAME?” At moments like these the deadpan clarity of another major recent graphic novel about a bearded radical, Chester Brown’s Louis Riel, might have been helpful.

This same critique applies to the writing. Eisner is admittedly crafting a polemic here, and as such is largely unconcerned with a “realistic” portrayal of the conversations that led to the story’s key events. But this can play havoc believability, even ones in which Eisner himself plays a role. Is his 2001 argument with a group of anti-Jew student radicals autobiographical or fictional? Their strangely Edward G. Robinson-esque dialogue (“There’s a Jew in every major government post of the Western world, see?” “Yeah, their plan is laid out in the “Protocols,” see?), and their open and transparent lambasting of “the Jews” (as opposed “Zionists” or “Likudniks” or “neocons,” far less problematic for P.R.) makes this unclear. There are a few footnotes to clear up some questions about the historical accuracy of the story’s events, but we’re not in From Hell or Louis Riel territory here. And obvious fudges, such as the cop who says he arrested Joly on almost a half-dozen occasions, needlessly obscure the fundamental truth of the book.

But Eisner’s penchant for broad caricature isn’t always a drawback. Rarely if ever has his gift for drawing shlubby schemers has been so deftly applied as it is here, where an almost never-ending succession of shlubby schemers create and perpetuate the Protocols fraud, first by plagiarizing Joly’s Dialogue, then by passing it off as an authentic minutes of a meeting of world Jewry and introducing it into the halls of power. These are shitty little men, who spend their shitty little lives in the service of shitty little rulers and ideologies, and who almost in spite of themselves created a fraud that outlived them and their overlords, a fraud whose destructive power is tragically ironic considering the pettiness of its origins.

The ability of central forger Mathieu Golovinski to disregard the truth in the service of his latest boss, whoever that might be, would be hilarious if it weren’t so nauseating. Eisner depicts him as being passed almost literally from hand to hand by a string of tsarist apparatchiks as Golovinski and his appointed quest to pin the problems of Russia on the Jews falls in and out of favor; it’s a clever conceit that suggests the mutable relationship to truth and loyalty ascribed by The Protocols to the Jews was in fact far more applicable to their enemies. In the end, Eisner reveals, this son of disgraced aristocrats, who created The Protocols in order to dissuade the tsar from liberalizing and had them published through a White Russian court mystic, wound up working for Trotsky. White may turn Red, but Jew-hatred is forever.

The rest of the book follows the journey of The Protocols around the world, from movement to movement, ever ready to adapt itself to a new political viewpoint. This despite being exposed as a transparent forgery as early as 1921. This event is detailed in the book’s central and critical passage, where a reporter from The Times of London (the spitting image of Basil Rathbone’s Sherlock Holmes, Eisner’s caricature is just a bit too on the nose) receives a side-by-side comparison of Joly’s original and Golovinski’s forgery from a Russian refugee. Eisner reprints long passages of text to demonstrate just how clear the plagiarism is, and the pages eschew all but the barest of cartooning in favor of getting the point across. Indeed, at the bottom of one page, the refugee asks the reporter incredulously, “Do you mean to go through all the 23 protocols, Graves?” It’s overkill, reminiscent of playing a first-person shooter and using the biggest gun in your arsenal to shoot an adversary you could just as easily knock out with a slingshot–but that’s Eisner’s mission. He wants to destroy this thing. And since he kicks off the passage with an article expressing belief in The Protocols written by no less a personage than Winston Churchill, we afford him that indulgence.