Posts Tagged ‘comics reviews’

Comics Time: Tussen Vier Muren/Between Four Walls (La Stanza/The Room)

June 12, 2009Tussen Vier Muren/Between Four Walls (La Stanza/The Room)

Lorenzo Mattotti, writer/artist

Oog & Blik, 2003

176 pages

$16 (€12)

What a lovely book. Consisting solely of 86 portraits (well, almost 86–we’ll get to that later) of recumbent couples (at least I think it’s couples, plural–we’ll get to that later too), this reproduction of a Mattotti sketchbook is a master class in how a few sketchy lines on paper can suggest a world of emotion and intimacy. The curve of two bodies on a bed (or at one point, memorably, on a beach); the differences between the ways eyes and mouths look when people are talking, making love, or simply luxuriating in one another’s company; playful POV shifts that transfer us from a voyeuristic fly-on-the-wall to a you-are-there observer under the covers at the foot of the bed; the placement of legs, arms, and hands on another person and what that immediately communicates about this relationship and this moment–Mattotti nails it all, with figurework that suggests calligraphy as much as portraiture. Perhaps I’m more conscious of cost with books that I actually plunked down cash for at MoCCA as opposed to bought with a credit card or received for free, but Tussen Vier Muren was my final purchase at this year’s show, from the Bries table, and I remember wavering: “$16 for a wordless little sketchbook by an artist whose work I’ve appreciated in theory but rarely in practice before today?” Golly am I glad I took the plunge. This is one of my favorite comics in quite some time, and a more romantic comic I think I’d be hard pressed to name.

Ah, but is it comics? I don’t go in much for that kind of debate, most of the time–seems to me that if something has given you enough cause to wonder if it’s comics, it probably is. But the issue is pertinent here, if only to help us understand what we’re looking at from page to page. Comics generally implies sequentiality, which itself frequently means a progression of sorts. So are these sketches meant to be “read,” in order, like a story? There are context clues for and against. If so, certain aspects of the book take on a whole new meaning. The book opens with a series of sketches that are both the roughest/loosest and most evidently erotic/sexual in the whole book–a thick, almost oily pencil line, one that slowly gives way to tighter, finer whorls and cross-hatching as the images lose their overt nudity and sexuality. Meanwhile, the male in these early drawings has a full head of hair, which soon disappears. So perhaps we’re meant to see these initial drawings as a portrait of a young couple in the full heat of infatuation; after a time, their need to prove their attraction to and affection for each other to the viewer diminishes as such things evolve into the shorthand language of a mature relationship. But what are we to make, then, of the drawings that crop up near the book’s midpoint, and again briefly toward the end, where the male figure/character at least appears to be a totally different person? Is the woman cheating? Are they playing the field, taking a break, seeing other people? Or are these sketches just inserted at random, devoid of any kind of narrative implications? Depending on where you fall on that question, the book’s final two images, which I won’t spoil for you, may take on entirely different, and potentially devastating, meanings. It’s all pretty rich for a silent sketchbook, and it will be enough to keep me coming back to this little thing for a long time.

Comics Time: The Gigantic Robot

June 10, 2009The Gigantic Robot

Tom Gauld, writer/artist

Buenaventura Press, June 2009

32 pages, hardcover/cardstock

$16.95

I bet you’ll be able to buy it from Buenaventura at some point

I bet you’ll be able to buy it from Amazon.com at some point, too

At first blush there’s a disconnect between The Gigantic Robot‘s content and its price point. I’m pretty sure that when I bought it at MoCCA, I was charged $20–which, hey, it’s a big hardcover book by Tom Gauld, a bargain at any price! As it turns out, however, it’s more a short story than a book, and the emphasis is on “short.” You get a splash-page single image on the right-hand page of each spread, and a brief (no more than seven words at any point) explanatory caption on the left-hand page. Gauld’s three-pager in Kramers Ergot 7 was heftier.

But look, essentially you’re paying for this like you would for a piece of original art, or at least that’s how I look at it. You’re not going to have many opportunities to buy a board book from a Kramers alum, right? And everything that Gauld’s work usually has to recommend it is present here in spades. The beautiful, densely shaded, cold black-and-white linework suggests Edward Gorey as replaced by a robot, while the story is Gauld’s purest distillation yet of his “Ozymandias”-like juxtaposition of immense man-made structures with the fleeting futility of human ambition. As always it’s reinforced by his unique character design, all massive torso with spindly legs and microcephalic heads, emphasizing raw size over any kind of reliable utility. You may quibble with this little parable’s punchline–having just read Ian Kershaw’s 1,000-page biography of Hitler, the post-war activities of the scientists who worked on the Reich’s “wonder weapons” are fresh in my mind, so the notion that a war machine with the potential for serious megadeaths would be allowed to lie fallow rings false to me. But the moral of the story is sound, and the pleasure of once again watching Gauld’s tiny lines coalesce into these massive monuments to hubris is undeniable.

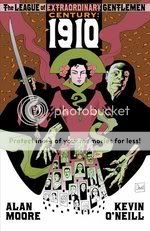

Comics Time: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 3: Century #1: 1910

June 8, 2009The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 3: Century #1: 1910

Alan Moore, writer

Kevin O’Neill, artist

Top Shelf/Knockabout, May 2009

80 pages

$7.95

Vastly more straightforward–and more like previous League of Extraordinary Gentlemen volumes–than its predecessor Black Dossier, Century: 1910 is a funny, creepy, nasty piece of work that encapsulates and articulates many of Alan Moore’s most heartfelt themes as explicitly and entertainingly as any book he’s ever done. (And he’s usually pretty explicit about that sort of thing, so that’s really saying something!)

Taking the rejiggering of the League’s line-up that occurred during the centuries-long sweep of Black Dossier‘s meta-story as read, 1910 joins Mina Murray, the rejuvenated Allan Quartermain, and their new teammates–the immortal gender-bender Orlando (currently male and generally going by Lando, making me want to say “Hello, what have we here?”), the gentleman thief Raffles, and the psychic detective Carnacki–as they attempt to thwart…something. They’re not quite clear on what it is, and base their investigation on little more than Carnacki’s ominous visionary nightmares. It could have something to do with the female heir to Captain Nemo, or with Jack the Ripper/Mack the Knife, or with a cult run by the sinister magus Oliver Haddo–they just know it’s gonna be bloody. Given Moore’s frequent depiction of the early 20th Century as the birthing of the proverbial rough beast, you can be pretty sure it’s gonna be bloody too.

What’s neat about this issue is that it’s what we in the blog business refer to as a done-in-one; I assume all of the Century books will interlock to tell one long story, and indeed there are plenty of plot threads to pick up down the line, but this tells a pretty satisfying story all on its own. In a way, the set-up, or I suppose the execution, reminded me a bit of the aspect of Warren Ellis’s early Planetary issues that I liked, or of the ending to Watchmen: the League doesn’t figure out what’s going on until it’s all over but the shooting. Moore obviously doesn’t care much for heroism, and the League’s never really “saved the day” in the traditional sense, but here they almost may as well have not shown up. Meanwhile (here’s the explicit part) Moore uses one of his simplest plotlines in ages to establish a direct link between violent misogynist sexuality and the unbridled bloodlust that ended up consuming the entire world not once but twice in the ensuing decades. Vengeance is sweet for the character involved, and you can’t help but get a kick out of it alongside her, but it’s also pretty fucked up, and if anything the League (the male ones, at least–Mina manages herself okay) just make it worse.

Insofar as the climactic bloodbath is representative of the century to follow, this can be seen as pessimism or resignation–but we’ve read Black Dossier and seen Moore’s efforts to establish the League’s true “heroic” legacy as one of imagination and a way of life freed from the dour, anti-life conservatism of their military minders. The question, I suppose, is whether that hedonistic heroism will win out, or if it will only succeed by carving out a space for itself in the Blazing World beyond and allowing our world to head right down the terlet. I mean, I know how it worked out in reality, I’m just curious as to how Moore will slice it in this alternate one.

If that all sounds like really grim reading, I suppose it is, but like I said, it’s also quite a funny book. The constant foreshadowing of the final massacre is so ominous it actually makes you chuckle from time to time the way a scary movie would–not from comic relief, but just because on some level you know what’s coming and it’s kind of amusing how ugly you already know it’s going to get. On the League end of things, the ongoing “are they or aren’t they” business about the Mina/Quartermain/Orlando menage is a hoot, especially the almost Scott Pilgrim-y way it finally comes out into the open, with some angry words that leave half the group wondering what the hell just happened. Kevin O’Neill, whose work simply looks like nothing else on the racks, gets to cut loose with a dock’s worth of leering scoundrels and ne’er do wells, and later with their comeuppance. Moore even injects some meta right into the mainline, with a cameo character who correctly identifies everyone and everything in the book’s world as fictional–he refers to Haddo, an Aleister Crowley manqué, as “Crowley manqué,” and works in a reference to Harry Potter’s Platform 9 3/4 as the launching pad for “the Franchise Express.” The book ends with a visual gag that’s like a shot from The Birds as covered by Troma. I’ll admit to skipping the prose supplement as always (tl;dr), but for pete’s sake one of the characters in it captured Fletcher Hanks’s Stardust the Super-Wizard! The whole comic is entertaining as all get-out, and even if you suspect that things are ultimately going to end very badly for our heroes, or with them washing their hands of our sordid world and fucking each other in Never-Never Land for all eternity, you’ll want to stick around to see how they get there.

Comics Time: Batman and Robin #1

June 4, 2009Batman and Robin #1

Grant Morrison, writer

Frank Quitely, artist

DC, June 2009

22 pages, $2.99

I wonder how long it will take everyone who complained about Morrison cramming so much information into Final Crisis and Batman R.I.P. that it went all the way back around again into vapidity to complain that nothing happens in this comic? (Answer: not long at all!) I’m a guy who loved how much shit was going on in any given issue of Final Crisis, a guy who very much bought into and enjoyed what Morrison was up to with his supercompressed storytelling techniques and the emotions and ideas they engendered, so on that level this comic’s a bit disappointing. You really can breeze through it in minutes, if you’re the sort of person who feels comfortable glazing over the art of Frank Quitely. But that of course is crazy, and that’s also the point of this comic–it reads to me like Grant Morrison’s reward to Quitely for sticking all the way through All Star Superman and delivering the Oscar-caliber character performances that 12-issue story required to get its point across. Here, Quitely just gets to run wild designing creepy new villains and a younger, fresher Dynamic Duo whose characteristic physical comportment and interactions he gets to invent out of whole cloth–a virtuoso performance of another sort entirely. His line is finer and scratchier than ever, no doubt a result of once again working without an inker enhanced by swapping his usual colorist Jamie Grant for Jim Lee’s go-to guy, Alex Sinclair. For his part, Sinclair gets to execute one of the book’s more amusing visual gags: The flying Batmobile that the megalomaniacal new Robin designed sure has a whole lot of red, doesn’t it?

Meanwhile we’re introduced to a trio of new bad guys: Morrison shifts from Lewis Caroll to another pillar of British children’s fiction about anthropomorphized animals to introduce the villainous Mr. Toad, there’s a new entrant into comics’ grand tradition of Head-On-Fire Guys, and the big bad, Professor Pyg, owes his look to a combo of Leatherface and Hostel with goons straight out of Alan Moore and Brian Bollan’s Killing Joke freakshow. Best of all, since they’re drawn by a stylist like Quitely, they’ve got a chance of sticking. On the hero side, Morrison pulls some neat tricks to show that Dick Grayson and Damian Wayne are on a learning curve–I particularly liked the bit where Damian dismissively refers to Alfred as “Pennyworth,” but then immediately adds a polite “Thank you” in the next word balloon: He may be an enfant terrible, but he’s trying. Elsewhere, under the ostensible cover of training Damian for the field, Morrison manages a dig at all the DC Comics where everyone calls each other by their first names as though every superhero battle is a high school reunion. To cap it off, Morrison and Quitely even crib from Geoff Johns’s delightful recent technique of adding a page or two of decontextualized images from future issues as a teaser for the rest of the run. This isn’t a book I instantly rushed to re-read like I would with each new issue of Final Crisis or R.I.P., but otherwise I think it’s safe to say that I’ve waited all my comics-reading, Batman-loving life for a monthly Batman comic that looks and feels like this.

Comics Time: Invincible Vols. 1-9

May 31, 2009Invincible Vols. 1-9

Robert Kirkman, writer

Cory Walker, artist, Vols. 1&2

Ryan Ottley, artist, Vols. 2-9

Image, 2003-2008

in the 120-144 page range each

$14.99 each

I don’t know what it says about me that I viewed my re-read of Robert Kirkman’s creator-owned coming-of-age superhero series Invincible largely through the prism of posts by other comics bloggers–probably nothing that isn’t deeply sad–but there you have it. First off, I thought of Tom Spurgeon’s recent post on Kirkman’s other long-running, unlikely-success indie title, the zombie-apocalypse survival-horror opus The Walking Dead, and how reading a massive chunk of it in one go reveals Kirkman’s studious, in-it-for-the-long-haul pacing. There’s certainly more going on set-piece-wise in Invincible than there is in The Walking Dead, but the principle is the same: For example, the titular superhero, teenager Mark Grayson, doesn’t have his series-defining confrontation with a secretly villainous character until the series’ third volume. Meanwhile, Kirkman takes Paul Levitz’s tried and true A/B/C-plot structure and stretches it out like a slow-motion camera filming a hummingbird–major players can spend a dozen or more issues being introduced in one- or two-page snippets before we even have any idea what they have to do with the book’s main character.

Naturally, reading as much of the series as you can in as short a period as possible flatters these aspects of Kirkman’s writing. But moreover, they help mitigate against Kirkman’s major bad habit: His characters either say exactly what they’re thinking/feeling, or they don’t say anything, or say “it’s nothing” when it clearly isn’t. There’s no in between, no subtext–they either come right out and say it or lie about it. To me, his inability to write convincing human interaction in that regard is the thing keeping him from being not just a really good, entertaining writer, but a great one. Which is frustrating, because his storylines and ideas are so engaging and frequently unusual that he’d really be a top dawg if he could master emotional expression. Now, I think this is already less of a problem in Invincible than it is in The Walking Dead, because Walking Dead is relentlessly bleak and serious book whereas Invincible is a much lighter one (albeit with plenty of serious moments); Kirkman’s inability to handle an emotionally charged conversation the way a great writer can has less impact in an action-adventure romp than it does in a character-driven survival-horror story. But (finally getting around to the point) it has even less of an impact when you’re plowing through 47 issues in a row and really letting the slowly unfolding, meticulously planned plotlines drive your reading experience rather than having the one-issue-a-month format dictate that you dwell over every scene. You can see the whole lovely forest without getting stuck on some of the gnarlier trees.

On to another blogospheric touchpoint: In his long series of posts on Kingdom Come and ’90s superhero comics, Tim O’Neil argued that Mark Waid and Alex Ross’s Kingdom Come marked the rise of the “momentist” school of superhero writing, which is less concerned with soap opera or traditional plots and more driven by attempts to serve up iconic moments for the characters at regular intervals. His best example of this was from a comic that predated the movement but obviously had a lot of influence on it–Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s “For the Man Who Has Everything” and the moment where Superman says “BURN.” and uses his heat vision as a weapon against Mongul. I think O’Neil was right in that this has led to an enormous amount of self-indulgent, hero-worshipping crap. It’s also led to some good stuff–I think Geoff Johns, at his best, does this stuff really well. (One moment I often think of in this regard was the bit in Green Lantern: Rebirth where Green Arrow used Green Lantern’s ring for a second and it totally kicked his ass, giving us new respect for GA and GL all at once.)

Kirkman, by contrast, doesn’t do Momentism at all. Maybe it’s just because these are creator-owned characters he just made up and they don’t have a lengthy history to play off of in constructing iconic moments. But, consciously or no, I think he actually hit upon the fact that iconic moments are a mug’s game for non-legendary superheroes, something pretty much every other indie superhero book misses entirely. Instead, he lets the ideas and the storylines drive the book, usually presenting the action in as flat a fashion as possible, so that he doesn’t distract from the loooooooong game he’s playing. In fact, outside the initial “learning to fly”-type stuff, the book’s big “moments” are almost invariably Invincible being stunned or pwned or both. There are plenty of “BURN.”-style moments where Invincible Finally Lashes Out Against His Enemy, but they almost invariably end in moral or physical disaster for the poor kid. It’s very much not a book about how awesome Invincible is, whereas 90% of corporate superhero comics these days are about how awesome Copyright Man or Team Trademark is. (The problem there is that very few characters actually merit such treatment and very few writers and artists can pull it off.)

Which reminds me: Invincible becomes much more interesting as a character the more he gets his ass kicked. I once wrote, back when the book was young, that the difference between Invincible and other teen superheroes like Spider-Man or the original X-Men or most of the Runaways is that while those kids were all geeks or outcasts, Invincible seemed like the kind of kid who’d pull into the high-school parking lot in his SUV blasting Joe Walsh’s “Life’s Been Good.” But that was actually giving the character too much credit–he wasn’t a Popular Kid anymore than he was a freak or a geek. He starts out as just sort of Generic Teen: He’s good-looking but apparently never seriously considered approaching girls and never seriously approached by them, he’s smart but doesn’t seem to be considered a geek by anyone, he’s got a crappy job but only because his dad insists he take one to gain a work ethic, he has no brothers or sisters, he reads comics but probably only because he’s a character in a comic book, he’s got one friend who’s sort of like a more high-strung duplicate of him, etc. Even when he finally starts developing the powers he’s waited most of his young adulthood to have, there’s zero angst about it, and nothing illicit either–he knew it was coming, he doesn’t hide it from his mom and dad, he instantly starts fighting crime. The wildest he gets with them is taking his buddy for a flight or two.

Then that series-defining confrontation occurs, and suddenly the superhero aspect of his life is the source of immense emotional pain, while at the same time he realizes that his name is far from accurate. The rest of the series, which by and large corresponds with Mark’s graduation from high school and entry into college, is basically about how fast he’s forced to grow up, the way the stress and danger of superhero life slowly chips away at his attempts to have a normal life, the high stakes of emotional involvement between godlike super-people, and so on. Oddly enough, Invincible is benefited in this regard by an art switch a lot like the one that happened in The Walking Dead. In that book, the clean cartoon line of co-creator Tony Moore gave way after an arc or two to the scratchier, edgier work of Charlie Adlard, just in time for the series to take a definitive turn for the darker. Here, the comparatively minimal. angular look of co-creator Cory Walker’s art is swapped out for the fuller, livelier stylings of Ryan Ottley. Ottley’s stuff is cartoony in a way you just don’t see from the Big Two and their SERIOUS BUSINESS books anymore, outside of books like The Incredible Hercules that manage to dance between the raindrops of the Momentist events and the realists and Image Seven disciples who draw them. But more importantly, it livened the book up in a big way, just as Invincible developed more of an inner life to display.

I think this change really hit home in that aforementioned series-defining confrontation (no, I’m not going to spoil it even though I can’t imagine anyone reading this deep into this review who hasn’t already read the damn book). What had been the sort of light-hearted “let’s make superheroes FUN again!!!” romp you see so many creators attempt, so many bloggers applaud, and so many readers ignore suddenly got ultraviolent. It was a huge tonal shift, one that the series occasionally reproduces, though it does so infrequently enough for the move to retain its ability to shock. (The book even has some meta-style fun with it in one issue, prudely cutting away from multiple sex scenes only to end the ish by depicting a horrendous beating and dismemberment in full, bloody, intestine-ripping detail.)

In these moments Ottley’s good-natured art suddenly feels like it’s being used as a weapon, while Kirkman demonstrates that he’s ready, willing, and able to completely upend the book’s status quo. Following his mutually unsatisfactory sojourn at Marvel, Kirkman would be the first to tell you it’s his total control over the book and its characters that enables him to pull off stuff like that, that enables him to tell you “anything can happen” and mean it and convince you that it’s true. That’s probably the greatest pleasure of reading nearly 50 issues of Invincible in a row: You’ve watched Kirkman grow as a writer, Ottley grow as an artist, and Invincible grow as a character (though you haven’t watched Bill Crabtree grow as a colorist, because he started off awesome and stayed that way–pastels! Brilliant!), so by the time you get to one of those anything-can-happen moments, you’re so attached to the character and the book he stars in that you just race through the pages hoping that whatever happens isn’t so bad.

Comics Time: Forbidden Worlds #114: “A Little Fat Nothing Named Herbie!”

May 1, 2009Forbidden Worlds #114: “A Little Fat Nothing Named Herbie!”

Shane O’Shea (Richard E. Hughes), writer

Ogden Whitney, artist

American Comics Group, 1963

14 pages

Read it at Pappy’s Golden Age Comics Blogzine

Buy it (I think) in Dark Horse’s Herbie Archives Vol. 1 from Amazon.com

Not to be a vulgarian, but holy fucking shit, this is what Herbie comics are like? I mean, I knew the basic look and set-up, taciturn fat kid with a lollipop is actually a terrifying war machine with godlike powers of destruction, it’s from the ’60s and it’s a funny in a weird art-out-of-time way. But my God! The comedy in this thing is a solid 40, 45 years ahead of its time. You could animate this thing and it’d feel right at home on Adult Swim between Aqua Teen Hunger Force and Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!, or make it a webcomic and stick it in your RSS feed along with The Perry Bible Fellowship,, or buy it from Buenaventura Press in a two-pack with the next issue of Boy’s Club. The two-panel tier, six-panel grid pages are really just perfect for a “set-up/punchline” gag structure with zero room for milking the humor out of things by taking too long with them, and for increasing the randomness of the juxtapositions. One panel, Jackie Kennedy is swooning with unrequited ardor for a morbidly obese child as JFK fumes in the background; the next, Herbie is soaring through the air on the back of a giant parrot. You know what I mean? The actual plot-based gags are similarly non sequitur–Herbie defeating an army of ghosts by suddenly being able to call the animals of the jungle to his defense by bellowing like Tarzan is the kind of thing you’d see in one of those two-minute sequences in The Family Guy where Stewie is suddenly reenacting William Shatner’s “Rocket Man” performance or Peter performs “Shipoopi” from The Music Man in its entirety. (I like The Family Guy; let’s not have that debate here.) Then there’s Ogden Whitney’s art, which is about 12 times as strong as it needs to be to make this work and 40,000 times more realistic. But it’s not just the contrast between the visuals and the subject matter that he has to recommend him; it’s also the angles he chooses for the planes of action within his panels, and his choices for the strip’s “actors”–the way the proud dads directly address the audience at the beginning just kills me. So does the visual shorthand he uses to depict Herbie planning his vengeance: a series of blackened thought balloons with bright red question marks in the middle. That’s exactly how I’m going to picture my own rage from here on out. For me it really all comes together in the final four panels, which silently culminate in a panel so deadpan it anticipates the awkward-pause comedy of everything from Space Ghost Coast to Coast to Curb Your Enthusiasm. Hilarious. I want these books now, badly.

(via Tom Spurgeon)

Comics Time: The Diary of a Teenage Girl

April 27, 2009The Diary of a Teenage Girl

Phoebe Gloeckner, writer/artist

Frog, Ltd., 2002

312 pages

$22.95

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Savage Critic(s).

Comics Time: Batman: Knightfall Part One: Broken Bat

April 17, 2009Batman: Knightfall Part One: Broken Bat

Chuck Dixon, Doug Moench, writers

Jim Aparo, Jim Balent, Norm Breyfogle, Graham Nolan, artists

DC, 1993

272 pages

$17.99

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Savage Critic(s).

Comics Time: Bonus ? Comics

April 15, 2009Bonus ? Comics

Kevin Huizenga, writer/artist

USS Catastrophe, 2009

4 pages

free with a copy of Rumbling Chapter Two, as far as I can gather

Buy it from the Catastrophe Shop

SPOILER ALERT

This thing’s cute: Two guys (previously seen at the end of Or Else #5, having a conversation told in illegible scrawls of differing lengths) sit across from each other, pondering a big question–or at least a big question mark, which hovers in between them. The man on the left pulls it down onto the table, cuts it into tiny pieces that are the shape of miniature question marks, tries to answer each constituent part with the help of some books, until finally all the little question marks snap right back into the big question mark. The guy on the right just grabs the little dot from the bottom of the question mark and shoves it into the hole formed by the circular part of the question mark. This apparently answers the question, which disappears. The guy on the right smokes a cigarette in celebration. “End.” The formal stuff is fun, the punchline panel made me chuckle, and I think maybe there’s even a lesson to be learned about not making simple problems more complex by way of trying to solve them. I think in an ideal world all our great cartoonists would knock out little unimpeachable one-sheeters like this all the time during their morning coffee.

Comics Time: Rumbling Chapter Two

April 13, 2009Rumbling Chapter Two

Kevin Huizenga, writer/artist

USS Catastrophe, 2009

36 pages

$3

Buy it from the Catastrophe Shop

What impressed me most about Rumbling, Kevin Huizenga’s adaptation of a dystopian/post-apocalyptic short story by Italian writer Giorgio Manganelli, is how effectively it conveys that whole Handmaid’s Tale/The Road things-fall-apart vibe while still residing squarely in Huizenga’s wheelhouse of formal play and finely observed transcendence-through-the-mundane detail. So you get a very effective vignette in which this alternate-future Glenn Ganges, an irreligious foreigner stranded in a country torn apart by a religious civil war, overhears a mother tell her kid it’s impolite to stare at Glenn, that the reason he wasn’t praying when the bells rang is because God doesn’t talk to him like He does to us; or, following that, a sequence where Glenn is picked up by a local to be driven to his boss the ambassador’s safehouse in the country and starts wondering if the man is going to do him harm, but then is slowly lulled to sleep by the rhythm of the passing countryside. Excellent dystopian stuff in both cases, but moreover, they both end up showcasing Huizenga’s preexisting strengths: I loved how the little boy’s confused/fascinated torrent of thoughts upon being introduced to the idea of an irreligious man were conveyed by an explosion of thought balloons cut off by the panel borders, and how Glenn’s long ride into the country was depicted by two panels featuring the pick-up truck’s sideview mirror jutting into the passing scenery, reflecting Glenn’s weary and then sleeping face. Meanwhile the wide array of warring factions gives Huizenga ample opportunity to design more of the kinds of symbols and logos that seem to burst out of his comics like automatic writing, and there’s a funny recurring bit that takes a Chris Ware-style enlargement of key words in a narrative caption to splash-page extremes. In other words it’s a comic that succeeds on a lot of levels all at once.

I actually think this material comes across better in the story’s current delivery mode, a standalone self-published minicomic, than it did in Or Else #5, the final issue of Huizenga’s Drawn & Quarterly one-man anthology, in which Rumbling‘s first chapter appeared. There it was surrounded by short pieces that were in some cases related enough to the main story to feel like a full-fledged part of it but in other cases really had nothing to do with it; the lingering feeling that all this stuff was connected served to mute the first chapter’s impact and hinder its momentum. In Rumbling Chapter Two, Rumbling‘s all you get, and the comic’s the better for it.

Comics Time: Cockbone

April 10, 2009Cockbone

Josh Simmons, writer/artist

self-published, 2009

26 pages

Buy it in Sleazy Slice #3 for $8 from Robin Bougie

There’s just no way to properly talk about this book without explicitly describing some of the things that happen in it so take that as a spoiler alert please

You know how in Martin Scorsese’s GoodFellas, we get introduced to Joe Pesci’s character with that whole hilarious “What do you mean I’m funny?” exchange, but in Casino, we get introduced to Joe Pesci’s character with him stabbing some guy repeatedly in the neck with a pen and then mocking him as he lies on the ground whimpering? You know how that difference kind of gets across the overall variation in tone between the two films? Josh Simmons’s In the Land of Magic has a bright yellow cover and starts with a fantasy parody sequence. Cockbone has a crumpled, grease-stained brown paper bag for a cover and stars like this.

“You pansy little bitch.”

“Kill the dog.”

“Kill the dog, faggot.”

Then–spoiler alert–the faggot kills the dog.

It’s safe to say that this comic contains the most extreme material I’ve ever actually come across in a comic. Imagine if the rape-murder sequence in Poison River were the length of an entire story and depicted with all the graphicness of Phoebe Gloeckner’s diagrammatic blowjob illustrations (where do you think the title comes from?), but with none of the clean, cool reserve of either. Even the blood splatter is angular and angry.

Cockbone is a non-stop litany of incest, animal cruelty, genital mutilation, murder, saturation bombing, homophobia, racism, and sexual depravity designed to make you as uncomfortable as possible, over and over again. The second you get over seeing a howling dog getting shot repeatedly until its ribcage explodes outward in jagged shards, you’ve got the main character’s brothers and mother repeatedly sucking him off to extract his hallucinogenic semen. Get a handle on the sight of a man’s wart-covered penis splitting apart and revealing a fishbone-like spine, and you’ve immediately got to deal with three guys peeling each other’s skin off as the beat each other to death, and then jetplanes bombing a city with little stick-figure people literally exploding from the heat. There’s just no respite, ever. And in the comic’s most memorable, haunting effect, it doesn’t so much end as give up–rather than actually showing what happens in the last two panels, Simmons superimposes simple caption boxes over the visuals that sum up their hidden contents in one or two words, as though the main character, Simmons, the world couldn’t bear to endure the real thing.

Simmons looks into the heart of humanity and what he sees comes wrapped in a grease-stained brown paper bag.

Comics Time: In a Land of Magic

April 8, 2009In a Land of Magic

Josh Simmons, writer/artist

self-published, 2009

20 pages

In my experience most cartoonists trafficking in this kind of material (most filmmakers and writers too) can’t help but convey that as awful as it is, it’s also kinda hilarious. The gore, violence, sexual brutality, humiliation, torture, animal cruelty–there could be some kind of serious point being made somewhere in there, but just as importantly, that shit is kinda cool! It’s fun to scare the straights, it’s a hoot to “go there.” And indeed there are elements in Simmons’s fantasy-world minicomic In the Land of Magic that could, at first glance, make you think that’s what he’s doing as well. His characters have always been on the cartoony, comical side, and when you’re drawing stereotypical elf-folk and wizards straight out of Patton Oswalt’s RPGer parody character on Reno 911, it’s not like they’re going to get less silly. Silliness is in fact the point when it comes to their Stan Lee’s Thor faux-olde fashioned dialogue (“Lothar–What fore dost thou lookest at, my love?”). And when the elf couple Lothar and Hester journey beyond the borders of their magic land to start exploring the Dark Forest beyond, there’s a page consisting almost solely visual double entendres that make it look like they’re 69ing or fisting each other. It’s funny!

SPOILER ALERT

Then Lothar does battle with Arachnad the Terrible, a battle that ends with Lothar saying the following to his fallen foe:

Poor little baby…Baby done got a broken neck, isn’t he? Can’t move, can you? Awww….poor little guy JESUS CHRIST I HAVE THE BIGGEST FUCKING HARD-ON!!

From there, Lothar strips naked, cuts a hole through the underside of Arachnad’s chin, bashes out Arachnad’s teeth, and fucks the wound so that the head of his penis repeatedly thrusts out through Arachnad’s gaping mouth until he ejaculates.

Yeah.

You know, even then, you could probably think that maybe this is all an exercise in seeing just how far we can go with this sort of thing. But I think the end of the book tells the tale, when Lothar forces the horrified Hester to hold his hands and endure his lovey-dovey blandishments, insisting that she have sex with him even as his once-again hardening cock drips Arachnad’s blood. “I-I’ve never seen you like this before,” she stammers before he forces her out of the hiding place she’d retreated to. I think that’s what Simmons’s work is about: terror that this is inside him, and an inability to do anything about it other than put it on display.

What makes Simmons’s brand of taboo-shattering impossible to write off, or shake off, is that behind the transgression there’s no smile. No smile at all.

Comics Time: Batman Year 100

April 6, 2009Batman Year 100

Paul Pope, writer/artist

DC Comics, 2007

230 pages

$19.99

Originally written on April 8, 2007 for publication in The Comics Journal

Over the past decade, the most innovative and entertaining examples of action cinema have gone in one of two directions. Some have used a stylized combination of wire work and digital tomfoolery to make it all look easy–wuxia movies, The Matrix (wuxia gone Western), 300 (wuxia‘s Western equivalent), Kill Bill Volume One. Others have gone for a lived-in, beat-down, de-glamorized vibe that makes it look damn hard–Casino Royale, the battle scenes in The Lord of the Rings, Kill Bill Volume Two.

Given Paul Pope’s futurist bent and Japanese influences, you might think his epic science-fiction alternate-future Bat-book would head in the former direction. Not so! From the thrilling opening sequence of Batman Year 100 onward, Pope makes it clear that he’s going to make his hero seem super by making everything he does seem as down-to-earth, and difficult, as possible. Frank Miller’s interior-monologue litanies of broken ribs and paralyzed nerve clusters notwithstanding, there’s never been a better depiction of the extremely physical nature of dressing up like a bat, running around city rooftops and picking fights with people. And in the hands of an action choreographer and stylist like Pope, that alone makes for a hell of a comic.

Pope’s obsession with the man half of the Batman–evident even in the antiquated, hyphenated way he frequently spells “the Bat-Man of Gotham”‘s moniker itself–was apparently a preeminent concern of the writer/artist’s from the get-go. The book’s copious extra features include an initial sketch sent to editor Bob Schreck, accompanied by a laundry list of handwritten questions pertaining not to where the character keeps his kryptonite ring or whether he and Catwoman are still an item, but his height, his build, what material his mask is made of, whether he can wear “square trunks like an Olympic swimmer” and which joints his costume might gather at. In notes written for the collection, Pope explains his fixation:

“My preference is to work on stories where I am free to completely design a fictional world–literally from the ground up. Take Batman’s boots for example. This guy would need a good, sturdy pair of boots…It’s long been a pet peeve of mine when you come across comic book artists who insist on drawing generic, featureless boot-like shapes beneath the ankles of their superheroes, as if boots were just vague, foot-shaped stumps molded out of colorful plastic blobs, resembling something you’d get out of a toy box at a dentist’s office…”

There’s a lot more where that came from–and that’s just the costume design. Perhaps that’s to be expected from Pope, who as an artist has frequently dallied in the world of fashion and is attuned to the dovetailing of form and function, style and substance with any well-dressed individual, superheroes included. But the “concealed human vulnerability” conveyed in his clunky clodhoppers and wrinkly elbows is concealed no longer the second Pope puts him through his action-adventure paces. The book opens with Batman being doggedly pursued by, well, dogs, across the familiar rooftop landscape of Gotham’s vigilante clique. This Batman doesn’t just toss a few Batarangs, launch a grappling hook and swing away to brood atop a gargoyle another day. When he jumps a 25-foot gap between roofs, trailing blood from a wound in his side, he actually has to pause to catch his breath and give his aching bones and muscles a chance to recuperate. (And to smirk at his frustrated canine pursuers, admittedly.) When he hides from a SWAT team in a child’s apartment, it’s with a sense of genuine peril should the kid rat him out–in his weakened state, he’d clearly get his ass handed to him. And when he finally turns the tables on the federal goons by attacking them in a stairwell, it’s clear he’s relying far more on the element of surprise and pure costumed bluster than on flawless martial artistry. This Batman could lose, and that’s what makes his adventures so much fun to follow.

The choice even makes thematic sense. The semi-dystopian setting of Year 100 is one of Pope’s now-trademark libertarian nightmare scenarios, a world where surveillance cameras are surgically grafted into the eyeballs of police dogs and the fact that Batman wears a mask and therefore can’t be identified presents a far more visceral threat to his governmental enemies than the fact that he’s suspected of murdering a federal agent. In the same way that Orwell’s free-thinking Winston is told by his torturers that he is the last human being, Pope’s Batman is memorable not because of any dazzling gadgets or superhuman displays of physical prowess, but because he eats, sleeps, keeps protein bars in his utility belt, wears a shirt that’s a size too small, talks with a speech impediment when he wears scary fake fangs to freak out federal goons, gets his ass thoroughly kicked every time he sees action, and requires a small support team consisting of a doctor, a tech expert and a motorcycle mechanic to help him get anything done at all. With each of the aforementioned acts he reasserts his irreducible humanity in a world classified and documented and categorized and bureaucratized to within an inch of its life. It’s all enhanced by Pope’s familiar stylistic tics–meaty and careworn faces, bee-stung lips, heavy brows, hair that hasn’t seen shampoo for a fortnight, clothes that bulge and bag and buckle, characters who clamber and carom down creaky stairs and through grimy alleys and around telephone wires. He’s not a number, he’s a free man. The physical is political.

And much to this fanboy’s delight, the Bat-portion of “Bat-Man” doesn’t go ignored. I wish I could remember the name of the online wit who pointed out the true ridiculousness of Batman’s outfit: Like an old Star Wars Halloween costume with the character’s picture plastered on the chest, the Bat-costume’s central motif is a freaking drawing of the animal it’s supposed to transform its wearer into. What kind of sissy-ass criminal would be scared of that? But to this Batman of the year 2039, the key to striking terror isn’t the animal itself, but the unfamiliarity it represents. Fighting against platoons of jackbooted federales with animalistic nicknames like the Wolves and the Panthers, Batman takes advantage of his sui generis state–none of these professional ass-kickers have ever seen anything like him–and uses it to scare the crap out of them. His mask is designed to distort his facial features into inhuman unrecognizability. He uses sonic enhancements to emit growls. He wears a set of porcelain vampire teeth. Put it all together and, as captured in a searingly intense panel depicting a motion-captured close-up from a surveillance camera, it’s the scariest Batman has ever looked and acted, even if his sleeves are too short. (Colorist Jose Villarubia nails that Blair Witch by way of One Night in Paris screen; he’s at his best with the neons and glows of the tech-y end of Pope’s world, rather than the Vertigo-style greens that sully the down-and-dirty stuff.)

If I’m lingering on business rather than story, that’s because the story itself doesn’t cohere nearly as well as the ideas and images behind its lead character. In a plot drawing heavily from post-9/11 fears of governmental intrusion and terrorist brutality–Pope being perhaps the only major comics artist (not counting Red-Meat Miller) to give the taboo against taking the latter as seriously as the former the middle finger it deserves–Batman, his little band of helpers, and Capt. Jim Gordon (presented here as a quid pro quo political appointee) uncover a small but serious conspiracy within the federal ranks to hijack a terrorist-developed doomsday virus for their own ends. Or something. To be honest, it’s kind of hard to follow, existing mainly as a platform upon which Pope’s characters declaim didactically about the wisdom of trusting the government, the depths of depravity to which terrorists have no problem sinking, the healing power of open-source information streams, and so on. It makes for a cute ending–one where Batman and crew avert the apocalypse not by kicking the Joker’s ass but by the counterintelligence equivalent of uploading a video to YouTube–and insofar as it relies on fulfilling relatable tasks (climbing up ropes, locating lost computer disks, remembering stuff), it’s refreshing. But in terms of presenting readers with a compelling and solvable mystery, one wishes Pope had taken as much time making it as solid and singular as Batman’s trunks. Toward the end, even the action starts to slip away, with a motorcycle chase that’s tough to parse and too death-defying by half. How about giving the Bat-cycle a flat tire?

But the book is redeemed by its final pages, where Pope makes the seemingly counterintuitive, extremely unorthodox choice to keep Batman’s secret identity a secret from both his enemies–and us. Is he, somehow, the same Bruce Wayne who cooked up the heroic identity way back in 1939? Is he a descendent who took up the mantle? Is he (most likely) just some guy who thinks privacy and decency need a human avatar in this crazy mixed-up world? He’s not telling, and neither is Pope, who leaves us with a final panel that brings us full circle by showing Batman frantically running away from pursuers who will never catch him. The specifics may get a little wonky, but that indelible wish to remain unfettered, unclassifiable and untouchable–even if you get the snot beat out of you from time to time for your troubles–is as good a reason as any to dress up in a costume, or read a book about a guy who does so.

Comics Time: Supermen! The First Wave of Comic Book Heroes 1936-1941

April 3, 2009Supermen! The First Wave of Comic Book Heroes 1936-1941

Greg Sadowski, editor

Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster, George E. Brenner, Ken Fitch, Fred Guardineer, Bill Everett, Will Eisner, Lou Fine, Dick Briefer, Jack Kirby, Fletcher Hanks, Irv Novick, Jack Cole, Al Bryant, Ogden Whitney, Gardner Fox, Mart Bailey, Basil Wolverton, Joe Simon, writers/artists

192 pages

$24.99

Looked at strictly as an archival project, this Greg Sadowski-edited and designed anthology of early superhero comics is, like Paul Karasik’s Fletcher Hanks collection and DC’s Jack Kirby omnibuses before it, a real “here’s how it’s done” moment. Entertaining, left-field subject matter; eye-pleasing design; tactile paper stock; color technique and reproduction values that neither hide the material behind the haze of nostalgia nor try to mask its primitive origins with out-of-place high-gloss modernity; manageable length and heft; art presented at a powerful but not brobdingnagian size. The ongoing efforts of the aforementioned editors and publishers, along with the likes of Dan Nadel and Craig Yoe, truly have us living in the Golden Age of Reprints.

But how does the thing read? Well, generally speaking. I have to admit I don’t feel that the book is quite the revelation that, say, Jog argues it to be. Taken as a whole the early superhero comics reproduced here lack both the transcendent artistry and metaphorical/philosophical vision of Kirby’s Fourth World Omnibus and the eerie, obsessive-compulsive, barely checked madness of Hanks’s I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets! Meanwhile, though the wordy foreword by Jonathan Lethem makes much of how these protean efforts present an array of paths not taken by the more codified superhero stories that followed, those of us who’ve put a lot of time into reading modern superhero comics and nearly as much into arguing on their behalf are used to hunting down fruitfully unusual avenues of expression in that genre from past and present alike. Moreover, for all their occasional flashes of genuine sophistication or bracing weirdness, most of these stories are overwhelmed by their rudimentary plots, wooden dialogue, omnipresent narration, and the sense that for all their high-pitched violence, the actual emotional and physical stakes for the one-dimensional “characters” involved are vanishingly small. Read a couple at a time, the stories are entertainingly zesty; stretched one after the other, you’re gonna need to put the book down.

But even if the book isn’t the “reverse-neutron bomb” Lethem makes it out to be, who said it needed to be one? There’s enough pleasure to be had in recognizing the plug-ugly goons, heavy-lidded dames, and even the earliest traces of Kirbytech in the former Jacob Kurtzberg’s contributions; or seeing just how much sharper was Jack Cole than his contemporaries in terms of comedy and layout. I’ll take any excuse to look at comics by Fletcher Hanks, with his neurotically repeated figures and forms; placing them in close proximity with, say, Al Bryant’s “Fero the Planet Detective” sharpens our appreciation for the latter’s comically capricious violence and memorably hideous villains. Soon to be a star outside the genre, Basil Wolverton crafts a sci-fi adventure with character and costume designs that alternately prefigure the undergrounds and Chris Ware and a comparatively complex story that evokes the macho codes of honor and friendship often found in its pulp-prose forebears. Will Einser and Lou Fine turn in a tremendous, print-it-as-a-poster-and-hang-it-up cover for “Samson,” and give us one of the great simple pleasures in superhero comics–a bold, attractively streamlined costume–in the red-and-yellow person of the Flame.

As you might expect, any number of panels and word balloons are internet-meme-worthy–just flipping through at random I came across one of my favorite, a scene from a Bill Everett “Sub-Zero” comic in which the villain takes the time to fix up some foamy shaving cream, the better to fit the captured hero’s head for the electric chair’s skullcap. But there are moments of weird beauty, too: Eisner and Fine’s Flame standing like a Greek god as he speaks with a beautiful woman; Wolverton’s armored spacemen colliding in battle; Fred Guardineer bringing a statue of George Washington to uncanny life; Kirby’s proto-Roger Dean Martian landscape. And while the variety of approaches on display here may not necessarily blow minds, they should at least open some eyes. In a time when the major superhero companies seem dead-set on creating the most uniform tone possible across their lines–black-ops badasses in spandex at Marvel, a hyperviolent pantheon at DC–evidence that superheroes can behave in any number of ways against any number of threats is indeed liberating, perhaps even necessary. Forget the turgid prose–focus on the weird beauty. That’s what I did.

Comics Time: Dragon Head Vols. 1-5

April 1, 2009Dragon Head Vols. 1-5

Minetaro Mochizuki, writer/artist

Tokyopop, 2005-2007

232-248 pages each

$9.99 each

Originally written on February 21, 2007 for publication in The Comics Journal

First, an admission: If it’s the post-apocalypse, I’ll eat it.

Second, an assertion: Even discounting my bias, Dragon Head is one of the most compulsively readable manga to reach an appreciable non-otaku audience (or at least this member thereof) in quite some time.

I found this somewhat surprising given DH‘s shaky start. Its first two volumes focus on an overbaked, if gut-level-gripping, high concept: Three high-school students are the sole survivors of a catastrophic train wreck in a collapsed tunnel deep underground. At this early stage the characters come out of Battle Royale central casting: Older boy Teru tries to do the right thing despite his mounting panic, younger nerd Nobuo bugs out and start doing things with knives and dead bodies, damsel in distress Ako is disarmingly wounded and pretty and ultimately more sensible than her two male companions combined, that sort of thing. Nobuo in particular is played to the cheap seats, going from zero to Lord of the Flies in the space of the first volume. Smart, detail-driven moment, like Ako awakening from a two-day coma to discover she’d gotten her period while she was unconscious and nearly going to pieces because her tampons were lost in the rubble, are few and far between.

By contrast, Mochizuki’s cartooning is vivid, memorable, even sensual, and seems to be where he’s deriving most of his pleasure here. However weak the psychological underpinnings of Nobuo’s freakout may be, Mochizuki renders its end result, the demonic face and body markings the kid gives himself using dead girls’ makeup, with graphic glee. Nearly wordless sequences throughout the second volume in which he chases Ako and later strips and paints her unconscious body utilize predatory pacing and intelligent image choices (a sharply turned head, a hand on a breast) to portray adolescent pre-sexuality gone vicious and sour. Mochizuki also evokes the impenetrable with evident relish, be it the walls of stone that hem the survivors in, the darkness that the kids are always trying to stave off with flashlights, lighters, and torched bottles of booze, or the mass of upturned seats, broken glass, torn-up backpacks and mangled limbs that fills the wreckage of the train.

Indeed, Mochizuki’s zeal for colossal depictions of the man-versus-nature conflict (a surprisingly rare sight in comics, for some reason) gives rise to a fairly major problem with Tokyopop’s translation work: In a world where so much action is the result of massive, indistinguishable walls of steam, stone, water, flame, earth, mud, and/or ash threatening to consume our protagonists, would it really be too much to ask for the publisher to translate the damn sound effects? They don’t even have to replace the Japanese characters–just run an English translation in smaller print alongside them and you’d be good to go. As it stands, without a telltale “RRRRUMBLE” or “HISSSSSSSSSSS” or “FWOOOOOSH,” the book’s many otherwise-silent sequences of natural disaster are extremely difficult to parse. Is that an ominous groan or an imminent collapse we’re hearing? Are Ako and Teru being overwhelmed by water or smoke or heat or their own overactive imaginations? All too frequently, if you don’t understand the kanji, your guess is as good as mine.

But all is forgiven once the inevitable showdown between sanity and face-painting, darkness-worshipping lunacy is over and the surviving kids finally make it to the surface world. We’re not entirely safe from wonky mental breakdowns yet; both Ako and Teru will, at varying points throughout the remaining volumes, weave in and out of catatonia or psychosis without much rhyme or reason. But as soon as they discover that whatever happened to their train tunnel happened to pretty much the entire rest of the world, the backdrop of their story expands exponentially, and their characters feel similarly enlarged. Their existential horror upon realizing that the atmosphere is full of enough soot to choke out the midday sun, their subsequent dazed, fumbling search for food, water, and news of the world, and Mochizuki’s you-can-taste-the-ash-in-your-mouth art for the sequence, are just the first signs that the book’s comparatively shallow action-thriller days are behind it. Had the book continued in that vein you might have expected the pair to become a cutesy, thrown-together-by-circumstance couple; instead their bond seems deeper and truer, driven by an instinctual need to survive and see that the other survives as well.

Sure enough, the greatest obstacle to their mutual survival turns out to be other people. Once again this could have been a minefield of cliche, but Teru and Ako’s dreamily horrifying journey among the human detritus of their dead world is where the book really takes off. A group of similar kids appears friendly, if slightly off, only for our heroes to discover that they blithely worship the “demon” they blame for the apocalypse they’ve experienced in a hard-to-shake ceremony involving gas masks and fireworks. A middle-aged woman in a motorcycle helmet takes them in, carving out a quiet, stately interlude for characters and reader alike in a refreshingly un-motherly way. Even the inevitable soldiers gone feral largely steer clear of the same old poses–granted, that’s how they start out, but soon a pair of them are joined with Ako and Teru more or less as equals, behaving and interacting as unpredictably as one suspects people in the real world would.

Through it all, the spectre of Nobuo hangs over Teru in particular, sometimes all but subliminally (one tremendous four-panel sequence shows Teru lying unconscious in the distance of identical shots of a rubble-filled scene, changing only in the fourth panel when Nobuo appears out of nowhere, mockingly squatting beside the body of his rival). He’s far more convincing and frightening an enemy when he’s treated as a source of guilt (why couldn’t Teru get his act together and save the poor kid, he wonders) than as a source of law-of-the-jungle fear. Mochizuki’s attention to detail regarding the headgear of the characters whom Teru and Ako stumble across later (they always seem to be sporting earphones or gas masks or baseball caps or motorcycle helmets or something) echoes Nobuo’s self-transformed skull and hints at whatever the title may really mean (by the end of Vol. 5, the only explicit reference is in the mutterings of an apparent lobotomy victim).

The overall effect is a nightmarish picaresque, like a cross between Children of Men and Apocalypse Now. With each volume better than the one before it, the perambulating structure pays off in spades. Get through the tunnel and you’ll want to see where the journey ends up.

Comics Time: Jin & Jam #1

March 30, 2009Jin & Jam #1

Hellen Jo, writer/artist

Sparkplug Comic Books, 2008

36 pages

$5

The first thing I thought during my initial flip-through of Jin & Jam was “Boy, this person sure likes Taiyo Matsumoto.” Then I started reading from the beginning and the first thing I saw was an epigraph from Black & White, aka Tekkon Kinkreet, by Taiyo Matsumoto. So it’s not like Hellen Jo is trying to hide the influence, which emerges not just in the wiry art and leering character designs but in the plot itself, involving various paired-off tweenage characters gettin’ in trouble and stickin’ it to the man. But we’re not in Matsumoto’s sprawling dystopian future cityscape, we’re in a cramped, just-left-of-normal version of San Jose, California. And that’s where I start to detect another, subtler influence: Jaime Hernandez and the Locas of Love & Rockets. As we watch Jam, Hank, Jin, Ting, and Terng do the shiftless-layabout teenage-wasteland thing, we observe little details about their California culture: the junk-food diets, the bike-riding cops with bike helmets and short-shorts, the angry Korean Presbyterian preachers and so on. Meanwhile, the fact that the title of the book is Jin & Jam even though when we meet Jam she’s already paired off with Hank indicates that there will be some kind of emotional shift taking place, breaking up or truncating one friendship as another blossoms. We even start to see it happen by the end of the book: As Jin and Jam take a fantastical ride on a swing set under the stars, the faces of their “friends” literally vanish, leaving Jin & Jam as the only real people in the book’s final splash page. Is this Tekkon Kinkreet or Wigwam Bam or just a jack of both trades but master of neither? Too soon to tell, but are you not entertained regardless?

Comics Time: First Time

March 27, 2009 First Time

First Time

Sibylline, writer

Alfred, Capucine, Jerome d’Aviau, Virginie Augustin, Vince, Rica, Olivier Vatine, Cyril Pedrosa, Dominique Bertail, Dave McKean, artists

NBM/Eurotica, 2009

108 pages, hardcover

$19.95

Gloria Leonard said that the difference between pornography and erotica is lighting; it stands to reason that in comics, the difference between pornography and erotica is linework. First Time, then, is definitely erotica. This collection of sexually graphic vignettes features high-class, high-quality European artists whose styles will be instantly familiar to readers of alt/art/lit comics here in the States, even if the artists themselves (most of them pseudonymous, I think) are not. But best of all, a couple of them are familiar. Yep, “Cyril Pedrosa” is indeed Three Shadows Cyril Pedrosa! And Dave McKean is indeed “Neil Gaiman” Dave McKean! Maybe it’s just me, but I think seeing cartoonists whose mainstream work you know and admire get smutty is one of life’s simple pleasures, like discovering the lovely but respectable actor you’re crushing on did an extensive nude scene back when everything was at its youngest and most pert.

Indeed, the reclamation of the erotic as something respectable comics creators can depict and respectable comics readers can discuss is something of a hobbyhorse of mine. Shouldn’t sex be something we tackle at least as often and as directly and with at least as much sophistication as we deal with violence and misery? Heck, shouldn’t it be something we tackle independently from violence in misery? This is a pretty terrific step in all those directions. In addition to bonafide critics’ darlings Pedrosa and McKean, every artist looks like they could have stepped out of a Petit Livre from Drawn & Quarterly or one of Fantagraphics’ Blab! storybooks or MOME guest spots.

Writer Sibylline seems to have either tailored the material to her collaborators or picked them to suit the material. “First Time,” a sweet story of a girl’s deflowering that comes with a funny twist ending, has an appropriately Top Shelf-ish vibe courtesy of the angular cartooning of artist Alfred, while the more self-indulgent topic matter of “Sex Shop” and “Fantasy” earn the more voluptuous, outwardly sexy curved lines of Capucine and Jerome d’Aviau respectively. “1+1″‘s story of a first-time girl-on-girl hook-up and the subsequent disappointment it engenders in one of its participants gets an animated look from artist Virginie Augustin, which nicely supports its initial whimsy and free-spiritedness and eventual heartbreak. “2+1”, with its tangle of bodies in a cramped apartment, slowly evolves from Tim Sale to Aeon Flux courtesy of artist Vince. Rica’s “Nobody,” the most Robin Bougie-ish of the stories what with its sex-doll subject matter, also boasts the most Robin Bougie-ish art, while Olivier Vatine’s “Club,” appropriately enough, reminds me of that New X-Men issue where Chris Bachalo helped reimagine the Hellfire Club as a strip joint in a tip of the hat to its NYC namesake. For those who’ve read the sweet, sensitive Three Paradoxes, Pedrosa’s aptly titled “Submission” may come as a shock, what with all the deep-throating and spanking and following orders to go look in the mirror with a mouth full of semen, but then again I think it was clear from that graphic novel’s bold visuals that Pedrosa could pull off pretty much anything. Dominique Bertail’s “Sodomy” has the most traditional sex comix look, I think, but its gender-reversal subject matter is strong enough that matter-of-factness is an apt stylilstic choice. Finally, McKean’s “X-Rated” combines manipulated film stills with cubist kama-sutra positioning for something that wouldn’t have looked out of place in a deleted Arkham Asylum scene where the Joker watched Batman get it on with Poison Ivy over the closed-circuit cameras. The whole project is a bit undercut by slightly wooden translation work from Joe Johnson, but only a bit. Overall it made me wish that more work like this was being produced. If you like your smut smart and your art sexy, seek this out.

Comics Time: Asterios Polyp

March 25, 2009Asterios Polyp

David Mazzucchelli, writer/artist

Pantheon, June 2009

344 pages, hardcover

$29.95

An extraordinarily easy book to read, Asterios Polyp is, I’m finding, a nearly equally extraordinarily difficult book to talk about. Frankly I think I just feel out of my depth. For example, cartoonist David Mazzucchelli has a long history of making art comics in Europe, and I’ve flipped through a few in the store or off my buddy Josiah’s shelf, but the only Mazzucchelli comics I’ve read from start to finish prior to this book are Batman Year One, Daredevil: Born Again, and that little comic with the spilled jar of ink he did for The Comics Journal Special Edition: Cartoonists on Cartooning. But hey, fine, I can fake it, I can certainly locate Asterios Polyp within the tradition of alternative comics. For exaple, it uses color and, to a certain extent, character design like a Dash Shaw webcomic or MOME contribution; it mixes imagery with external narrating text like Chris Ware, only with several orders of magnitude more room to breathe on the page, like Ware filmed in slow motion. That, I get.

What I’m having harder time with, where I feel really out of my depth, is in trying to locate the book’s story content. Asterios Polyp is a highly lauded, award-winning “paper architect,” i.e. a guy whose designs are awesome but have never actually been built, who divides his time between Manhattan and the Ithaca, NY university where he is a professor. We join his story already in progress, as a fire consumes his ratty, messy, porn(?)-soundtracked bachelor pad. Asterios does not pass Go, does not collect $200, proceeds directly from fleeing his apartment in the rain with his wallet and a handful of knicknacks and watching the fire department fight the fire down into the subway and back up and out at the Port Authority, where he takes a bus to the middle of nowhere and gets the first job he can find (as an auto mechanic) and crashpad he can find (renting a room from his boss at the auto shop). From there we bounce back and forth between revelatory events in the present day and key events in the life that led him there, mostly having to do with his ill-fated relationship with the talented but somewhat timid sculptor he was once married to.

In other words, it’s very Woody Allen, very Philip Roth, very New Yorker. A sophisticated urban aesthete unsuccessfully balances the life of the mind with the life of his weiner and then wonders where it all went wrong; his life is contrasted with that of the spirited younger woman he can never quite get a handle on and various other sophisticated urban aesthetes whose arrogance and eccentricity he deplores yet cannot see within himself. And there’s my problem: I know enough about that stuff to recognize the template, but I don’t know enough of it to know if it goes beyond using the template into wholesale swiping and/or rote recapitulation. The best I can do is say “Well, this reminds me somewhat of the Woody/Alan Alda bits in Crimes & Misdemeanors.” I’m simply not well-read enough in this area to comment beyond that. Ask me to speak authoritatively about the next Neil Marshall movie and I can probably handle that, but this? Donnie, you’re out of your element.

What I can say with confidence, however, is that I enjoyed that story immensely. And a big part of that is because this isn’t a Woody Allen film or a Philip Roth novel–it’s a comic, and there’s no mistaking it. Yeah, the basic story could be told in other ways, but if you wanted an illustration of that old saw that you should be able to look at a comic and determine why it’s a comic and not a movie pitch or a short story, look no further. Mazzucchelli clearly had a blast drawing this thing.

My favorite ambitious graphic novels of recent vintage have been pretty manic and information-heavy in terms of the visual approach–Theo Ellsworth’s Capacity and Josh Cotter’s Skyscrapers of the Midwest spring to mind, and even Dash Shaw’s Bottomless Belly Button feels dense and claustrophobic compared much of his other recent work, if only for the lack of color. Asterios Polyp, on the other hand, is airy and light from start to finish, like giving your eyeballs a breath of fresh air. There are all kinds of panel layouts, splash pages, and stand-alone images here, popping right off the big white pages, and the CMYK colors are just a pleasure to look at.

Meanwhile, it’s almost unspeakably clever. Mazzucchelli gives each major character and setting its own color scheme, that’s apparent from the start–Asterios is bright blue, while his wife Hana is bright pink. But oh, the places Mazzucchelli goes with that! By the time Asterios takes Hana to meet his mother and invalid father, he’s wearing a pink checkered jacket, while she has on a blue shirt. In a passage meant to illustrate how our memories slowly refine our original experiences “because every memory is a re-creation, not a playback,” Asterios’s remembered Hana slowly morphs from having a pink shirt on against a white background to wearing a blue shirt against a blue background. And in a much later scene which I’m going to try hard not to spoil, where the two encounter each other long after their divorce and after myriad transformative experiences, the color scheme is totally different–all oranges and greens. Meanwhile, “neutral zones” in both dreaming and waking life are yellow and purple. And let me assure you that as far as the use of color goes, that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Then there are the countless clever references to the history and art of cartooning. Given our hero’s occupation and preoccupations, there are quite a few mini-essays on architecture, philosophy, design, music…and they’re drawn and lettered like something out of Understanding Comics. A Latina chef swats flies on the ceiling and looks like she could have gotten off the plane from Palomar yesterday, while her band’s drummer sports a “Los Bros” sticker on his drumkit. Asterios’s dapper in-his-youth father looks like he stepped out of a Seth comic. The Midwesterners who take Asterios in–Stiff Major and his zaftig wife Ursula, and no, Mazzucchelli is clearly not above having some Vonneguttian fun with names–could be thrown up on the screen in a Disney/Pixar production tomorrow. Hana I can’t quite put my finger on, but she’s got a distinct ’50s/’60s illustration vibe, part Charles Addams part something else I’m too slow to pick up. Asterios himself is given to standing in profile and holding a cigarette like Eustace Tilley holds his monocle. His teaching career reads like Art School Confidential from the professor’s perspective. (Student: “I’m thinking about adding fenestration to this planar surface…?” Asterios: “How about just putting a couple of windows in that wall?”)

None of this would matter, or at least it would matter very little, if the comic weren’t a series of emotional hooks and twists and high points and explosions, which it is. The dream sequences are uniformly strong, with one involving a flooded subway station-cum-dock so evocatively drawn–thick washes of purple ink, rough crosshatching for one of the first times in the whole book–that I could practically hear the echoing slosh of the water in the tunnels. Asterios’s unique, virtually constant headshape (how have I not talked about this until now?) essentially requires him to be drawn in profile, so the few times we see him turn toward us (again in a dream sequence, notably!) are stop-and-pay-attention moments. The book’s bravura sequence (you’ll hear about this a lot) condenses the couple’s entire life together into a series of snapshot images of Hana’s various movements and bodily secretions; here’s one case where my familiarity with this technique bred nothing but admiration for seeing it so well done. The ending…I’ll say I imagine it will be controversial and leave it at that, but I got a kick out of it.

The real knockout moment for me, though, came during the pivotal argument that stories like this inevitably include, the storm that built for years yet ultimately came out of nowhere and nothing was the same after that. You spend the build-up to it noticing that something is awry, something in the way Hana has been drawn, something in the way there seem to be two or three things going on at once in the interactions between Hana, Asterios, and the other characters involved (including a memorable little imp named Willy Ilium in the book’s Clare Quilty role). Once it gets going, once the pink-and-blue color scheme starts shifting appropriately and the linework and coloring get scratchier and choppier and angrier, you’re rooting for Hana all the way, you think that finally the beef you’ve been accumulating on her behalf is going to get the apocalyptic airing it deserves. And then…and then…BAM, a line you just did not see coming at all, making it all the more devastating, because after all, neither did Asterios. I think this particular exchange may open the book up to charges that it embraces the same sexism it nominally deplores in its characters, but to me it’s the human element that comes through, not the gendered one. I read this scene and said “My God” out loud on the train. (You really need to read the book to get what I’m talking about, I suppose, and it doesn’t come out until June so unless you somehow ended up with a review copy months ago like I did I guess that’s difficult, but do me a favor, bookmark this and come back later and see if you think I’m right, okay?)

I may not know ahhht, is I suppose what I’m saying, but I know what I like. And I like Asterios Polyp a lot. It’s certainly a book to savor. I suspect it’s a book to treasure. I guess it wasn’t that hard to talk about after all.

Comics Time: Ojingogo

March 23, 2009Ojingogo

Matthew Forsythe, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, September 2008

152 pages

$14.95

Ojingogo reminds me of the immersive, action-intensive creature comics of Fort Thunder alums Brian Ralph and Mat Brinkman released by Highwater Books earlier this decade, books like Cave-In and Teratoid Heights. Heck, you could lump Brian Chippendale’s Maggots in there too if you wanted. Little critter guys wander around meeting other weird critters who grow or shrink or try to eat them in various configurations. There’s some video game logic to it, some children’s book overtones too. It’s a fun template.

But where Matthew Forsythe falls short of the Fort Thunder gang is in creating interpretable, continuous environments in which these adventures take place. Teratoid Heights, for example, was rigorously laid out from panel to panel; no matter how odd the protagonists or how nightmarish or isolated the space in which they moved, you could easily see the continuity from one panel to the next, to the point where he could cut to another character for panels or pages at a time and the second he returned you to the original character you still knew where you were. In Cave-In, Ralph’s sumptuous, textural backgrounds provided a sense that you were moving through a concrete, cohesive space. Maggots‘s frequently blacked-out backgrounds removed that tool from Chippendale’s continuity-of-action arsenal but provided a strange sense of unity all their own, while his intuitive Chutes ‘n’ Ladders layouts literally forced you to increase your concentration on continuity.

Ojingogo offers no such aid. Cuts between characters are frequent and sudden, with little to indicate why we’re switching viewpoints or where we’re switching our viewpoint to. This in turn makes it difficult to string together behavioral causes-and-effects for the characters and what they do. I was frequently at a loss as to why characters who seemed friendly were now fighting or vice versa, or why characters who were together were now separate, and so on. And when you have that much trouble figuring out basic things like the relationships between the protagonists, the creature-feature flights of fancy–growing, shrinking, transforming, etc.–become even more difficult to contextualize. By the end of the book I was just kind of turning the pages and looking at the pictures as much as I was reading the comic. There are certainly pleasures to be had in reading the book that way: Forsythe’s Koreana (is there such a word?) character designs are delightful, his line and use of graytones are pretty much perfect for this kind of comic, he has a real knack for body language (there was one sequence in which a Brinkman-esque giant squatted down to take a look at something that really strcuk me), and there are occasional moments of humor that made me chuckle (like when a pair of characters set up one of those box/stick/string traps to try and capture another creature, but it turns out he’s now like five times as big as they are, and he bounds past them, and as they stand there stunned, the box-trap falls shut on nothing). But with so little in the way of continuity of action or imagery, it’s a lot like reading little vignettes at random–you just couldn’t immerse yourself in it if you wanted to. Maybe this is a function of the book’s original life as a webcomic, but it makes for a frustrating read as a graphic novel, because you know how well it could work.

Comics Time: Cold Heat #2 & 4

March 20, 2009Cold Heat #2 & 4

BJ and Frank Santoro, writers/artists

PictureBox, Inc., 2006/2007

24 pages each

$5 each

Read it for free at ColdHeatComics.com

Originally written I don’t remember when for WizardUniverse.com’s Thursday Morning Quarterback feature

COLD HEAT #2