Posts Tagged ‘comics reviews’

Comics Time: Solanin

November 20, 2009

Solanin

Inio Asano, writer/artist

Viz, October 2009

432 pages

$17.99

It’s important not to oversell this book, because author Inio Asano clearly realizes how important it is not to oversell what happens within it. A slice-of-life story involving the amiable but aimless lives of a small group of recently graduated college classmates and the band that alternately provides them with a potential avenue for personal growht and a means of staving off exactly that, Solanin is the Goldilocks of twentysomething pop coming-of-age comics: Not too angsty, not too twee, not too cutesy, not too arch, but just right. The emotions and concerns of its main character, happily unemployed Meiko and her unhappily underemployed boyfriend Taneda, strike me as finely observed and plainly told. The conviction that you must be overestimating your own talent; attempting to fix in someone else a problem present in you as well; the humor-based rhythms of a long-term relationship; the automatic bump upward in feelings of maturity that takes place when living on your own; knowing you must find some direction for your life, yet only really knowing it in the abstract, yet somehow still feeling just as pressured by this as you would if it truly were an immediate matter of life and death; your first real peer-to-peer conversations with your parents; the powerful presence of art and leisure activities, as much of a staple as food and showers; the simultaneously comforting and discomfiting way that life can quickly fill a hole left by trauma or tragedy…it’s all just laid out there, as if all the characters and the author and the audience alike can do is simply take it as it comes. It feels leisurely and true.

Amid the overall high quality proceedings, there are some stand-out moments here, too, from a judicious few playful formal tricks with captions and speech lettering, to a series of kick-ass rocknroll pin-up poses in the Jaime mode that you’ll wanna scan, print, and hang on your wall, to some really fine and sensitive writing surrounding a pivotal plot twist that could easily have thrown the whole project out of whack like an overloaded washing machine. And if the characters are all a bit glamorous-looking compared to their scrupulously realistic plights–beautiful, button-nosed, sloe-eyed women and stylish, bespectacled, well-coiffed men, drawn with the lovely machine-precise slickness I’ve come to associate with the kinds of mainstream manga that find their way to readers like me–well, you know, that’s okay too. It’s fun to watch idealized versions of ourselves beset by the same problems we face. If you liked Gipi’s Garage Band, or the non-fighting parts of Scott Pilgrim, or the non-astronaut parts of Planetes, this one’s for you.

Comics Time: Archaeology

November 18, 2009

Archaeology

James McShane, writer/artist

self-published, September 2009

80 pages

I forget what I paid for it. $10, maybe?

I can’t find anyplace to buy it, but here’s James McShane’s website and blog

Wouldn’t be surprised if it ended up in the Buenaventura Press shop

This thick little minicomic does a lot of things right. First of all there’s the format itself: cardstock pages, folded into a fat little brick, then cut, I believe, with a bandsaw. It’s a delight to hold and let your fingers trace the bumpy edges of the pages; it’s like the anti-newsprint. Then there’s the idea for the concept itself, which won me over the second I figured out what it was: a chronicling of the contents and environs of his childhood home inspired by his mom’s moving out of it. Most of the book is just a shot of a room, a door, a lamp, a tree, a driveway, a hose–one small drawing per page, so intimate I wonder if they were drawn from memory. Flipping through the book’s thick stock ends up feeling like opening a tiny door into this house with each turn of the page. Moreover, McShane glides effortlessly in and out of deviations from the standard operating procedure–there’s a funny sequence of him popping up into the dusty attic and wondering what the heck’s up there (turns out to be nothing); an evocatively minimalist depiction of him and his mom strolling through the neighborhood, juxtaposing little suburban landscapes and still lifes with shots of the pair looking around against a blank background. Finally, McShane sticks the landing with a quietly bravura sequence in which his memories of the house begin to blend together even as he rakes its yard, with a tree suddenly appearing in front of a door and an obviously cherished duck-shaped lamp superimposing itself upon nearly everything, a focal point for years and years of lived experience. McShane’s Porcellino-influenced style is a perfectly breezy and simple complement to this perfectly breezy and simple comic, which nails this specific set of circumstances and sensations just about as well as you could imagine. Very well done.

Comics Time: Follow Me

November 16, 2009

Follow Me (Backwards Folding Mirror #3)

Jesse Moynihan, writer/artist

Bodega, 2009

120 pages

$10

This book’s a tough nut to crack, mostly, I think, because it doesn’t work. There are plenty of familiar altcomix elements present here, from slacker/douchebag observational slice-of-life humor, to gross-out gags and dick jokes and sex comedy, to little fantasy creatures having incongruously realistic and vulgar misadventures, to stream-of-consciousness psychedelic transformations and explorations. All that stuff has been done a million times, and in variations of Moynihan’s knowingly ramshackle black-and-white line to boot–you’ll detect echoes of Matt Furie, Mat Brinkman, Brian Chippendale, Lisa Hanawalt, Alison Cole, Theo Ellsworth, and probably a lot more besides. That said, Follow Me doesn’t feel derivative to me, thanks to Moynihan’s strong, winningly lo-fi character designs and “acting.” His main character, a little dude in a gnome hat, is a pleasure to watch as he’s haplessly buffeted by his own venal impulses and his world’s unpredictable metaphysical freak-outs; he gives Moynihan an opportunity for several standout moments, from his convincingly bewildered look as he gets sucked through a vortex to a goofy little dance he does in which his long shadow effortlessly creates a sense of harsh, bright lighting, a very cool effect.

And yet never does this self-evidently very personal vision burst through the “bubble” of its author’s headspace and communicate its vision of the world to me. I’m sure you don’t need to hear me repeat how much I enjoy comics whose impact is primarily emotional rather than logical, but in such cases I can at least make emotional sense out of what I’m reading due to visual continuity and a tonal through-line, or conversely a tonal juxtaposition,. Here I can do no such thing. Follow Me‘s elements sit awkwardly and uncommunicatively together. I have no idea what the “I can suck my own dick” gags and poop jokes have to do with extended visual riffs on death and multiple planes of existence. And rather than telling an emotional story, the too-frequent, too-abrupt transitions and extended visual extravaganzas just feel like a repeated “and then, and then, and then, and then, and then…” It feels less like daring and more like formlessness. Meanwhile there’s one out-of-nowhere chapter that’s as ill-advised a meditation on race as I’ve seen since David Heatley’s My Brain Is Hanging Upside Down. Much more so than most of the comics that bear the name, this feels like a diary comic, meaning it’s of value primarily to its maker. Which is fine, but caveat lector.

Comics Time: Reykjavik

November 13, 2009

Reykjavik

Henrik Rehr, writer/artist

Fahrenheit, June 2009

48 pages, hardcover

I got it for the low low price of $5 at MoCCA

Buy it from Fahrenheit…? I think?

FOOM! FWOOOSH! KRAKKA-DOOM! Abstract Comics contributor Henrik Rehr’s Fahrenheit is like the purely visual equivalent of a sound effect. Utilizing chops earned through years of more traditional cartooning, Rehr seizes the canvas of abstract comics with a vengeance, crafting a dynamic and frequently stunning–dare I say it?–page-turner, with nary a narrative element to be found.

Rehr is working in pure black and white, reproduced on a slick page stock that gives its expansive visuals a deep and expensive look. His “story” is structured primarily from spread to spread, and in each, one can detect a particular visual inspiration: the whorls of a fingerprint, the activity of unicellular organisms, waves, fire, smoke, a jungle, and in the book’s most memorable moment, a shattered pane of glass. There’s even one spread that looked like ghosts to me, though in that case and all the others, nothing is recognizable as such–Rehr deploys just enough visual cues to get the idea across before riffing off into the stratosphere with them. The emphasis throughout is on motion, with the eye pushed, pulled, and even thrown from one end of the spread to the next by wafting forms, exploding panels, or great ribbonlike curves. At times it looks like nothing so much as the stormy sky of a Dore print blown up to unrecognizable size. The context is gone, but the dynamism removes. This book really puts the “action” back in “abstraction,” and at five bucks–less than most minicomics!–it was an absolute steal. Snag it if you see it at a show.

See a preview below:

Comics Time: Funny Misshapen Body

November 11, 2009

Funny Misshapen Body

Jeffrey Brown, writer/artist

Touchstone, 2009

320 pages

$16

It’s a simple but effective tactic: Jeffrey Brown almost never draws his action straight-on. We see his autobiographical adventures at a three-quarter angle, or from slightly above and behind him, or with cuts to close-ups. When you factor in the seeming rapidity with which his tiny panels flash by, the effect, rather than one of sitting there watching actors, is like peering into a world, the space described with POV shifts and glimpses of corners and floors and rear walls and “extras.” I know I’m sounding like a broken record here–I’ve reviewed a lot of Jeffrey Brown comics and said this sort of thing in most of those reviews–but it just feels necessary to point out as often as possible that there’s a lot more going on, visually, than what’s let on by even the back-cover blurbs of his own books, let alone by people who’ve got a special monogrammed hatchet they break out in his honor.

As is usually the case with Brown’s nonfiction and memoir work, Funny Misshapen Body‘s carefully curated selection of topics and anecdotes belies the surface-level meandering and structurelessness of its narrative. Brown’s basically telling two stories here: the stories of his physical and artistic/intellectual development. That in itself is a revelation, because it’s not like the two intertwine or inform one another in any real way in the segments we see here. But to Brown, clearly his lifelong love of comics, his long and losing struggle to find a fulfilling artistic outlet, and the eureka moment(s) that bridged the two are just as fundamental to his physical existence as his Crohn’s disease, his physical fitness or lack thereof, even going through puberty. (I get the feeling the sex stuff in here would be much more fleshed out if he hadn’t already done several books on the topic.)

Maybe it’s this focus on the basics that enables him to depict the events of his life with such a winning blend of dispassion and good humor. Brown tackles a lot of material here–middle-school bullying, romantic obsessions, creative triumphs and rejections, the onset of sex as a going concern, inebriated and intoxicated collegiate shenanigans–that quite frankly loom on my own personal mental landscape like fucking Stonehenge. It’s almost bizarre to read a memoir that tackles these things from a seemingly undamaged place. But the two parallel narratives complement each other in such a way that it’s quite convincing. Brown’s story is one of seeking a compromise with the demands of his body and seeking no compromise with the demands of his art. He got to the finish line in both cases, and I guess I’d be pretty settled too, then. That it makes for perhaps his best book to date is just gravy.

Comics Time: Refresh, Refresh

November 9, 2009

Refresh, Refresh

Danica Novgorodoff, writer/artist

adapted from the screenplay by James Ponsoldt

based on the short story by Benjamin Pierce

First Second, 2009

144 pages

$17.99

Beware of those epiphanies! They’ll get you every time. Like Novogorodoff’s previous book Slow Storm, Refresh Refresh creaks under the weight of meaning with which every scene is imbued. Every email from its latchkey-kid teenaged protagonist to his soldier father abroad is a poetic reverie about the emptiness of lives touched by war. Every conversation between his friend and his friend’s kid brother is an object lesson in how violence and hierarchical power relationships infect those raised around it. Every bully, every cute girl, every wild animal is a metaphor first and foremost. Once again, there’s a belief-beggaring twist involving violence that dances up to the edge of murderousness in a way that simply doesn’t flow from what has come before, and in this case is actually difficult to parse logistically. And once again, there’s one last desperate night where visions are had and this topsy-turvy world almost makes sense before it all fizzles out and fades away. By the end, I found I didn’t care whether the book’s trio of teen leads ever broke free of the stultifying pressures that were slowly crushing them, but I sure as heck wanted the author to!

That said, one thing that really surprised me about this book was the art. When I saw that Novgorodoff had (with the exception of one key sequence) subbed out her memorable gray watercolor washes for a more traditionally drawn style, complete with acidic colors by hired guns (“Color by Hilary Sycamore and Sky Blue Ink; lead colorist: Alex Campbell”), I shook my head in dismay. Here was the most distinctive thing about Novgorodoff’s earlier book, and now it’s gone? But Novgorodoff’s got the chops for her pencil-and-ink work to stand on its own without the more dramatic painted style supplementing it. It makes for a fluid read, and in such cases as the predatory Army recruiter who intersects with our trio of heroes at several key junctures, it’s a fine conveyor of character information.

I just wish it was being deployed in service of a story a little less beholden to the set-up of literary fiction at its most obligatorily portentous. You know what’s a good point of comparison here? Gipi’s Notes for a War Story. Both are bildungsromane about three teenage boys caught up in the moral, financial, and physical uncertainty of war. Both are drawn in a thin-line style that emphasizes the characters’ awkwardness and vulnerability, but also makes moments of violence that much more impactful. Both are published by First Second. But one feels like a comic, while the other feels like a short story with drawings. Perhaps it’s the “adaptation of an adaptation of a prose short story” set-up that’s the problem, I dunno, but I do know the problem’s there.

Comics Time: Mome Vols. 14-16

November 7, 2009

Mome

Vol. 14: Spring 2009–Kaela Graham, Adam Grano, Derek Van Gieson, Laura Park, Olivier Schrauwen, Gilber Shelton, Pic, Dash Shaw, Ray Fenwick, Ben Jones, Frank Santoro, Jon Vermilyea, Sara Edward-Corbett, Conor O’Keefe, Emile Bravo, Lilli Carre, Hernan Migoya, Juaco Vizuete, Josh Simmons, writers/artists

Vol. 15: Summer 2009–Kaela Graham, Andrice Arp, Tim Hensley, Sara Edward-Corbett, Ray Fenwick, Conor O’Keefe, T. Edward Bak, Gilbert Shelton, Pic, Nathan Neal, Noah Van Sciver, Robert Goodin, Dash Shaw, Paul Hornschemeier, Max, writers/artists

Vol. 16: Fall 2009–Kaela Graham, Archer Prewitt, Ted Stearn, Dash Shaw, Lilli Carre, Conor O’Keefe, Ben Jones, Frank Santoro, Jon Vermilyea, Nicholas Mahler, Laura Park, Nate Neal, Renee French, Sara Edward-Corbett, T. Edward Bak, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds, Gary Groth, editors

Fantagraphics, 2009

Vol. 14: 120 pages

Vols. 15-16: 112 pages each

$14.99 each

Things kinda went off the rails here, no?

Like, looking at that list of contributors, you can see some standouts: The Cold Heat material from Jones, Santoro, and Vermilyea is not the strongest Cold Heat material in the world but it’s imaginative and, particularly with Vermilyea at the drawing table, sharply delineated, as is Vermilyea’s delightfully sick solo material. Josh Simmons impresses with his blackly comic strips, particularly a memorable number involving homunculus-sized versions of Tom Cruise and Michael J. Fox grinning soullessly at the assembled paparazzi. Tim Hensley kills it as always with the concluding chapters in his Wally Gropius saga, featuring peerlessly communicated body language perhaps the greatest anti-climax in comics history. I think this is some of the tightest material we’ve seen yet from Sara Edward-Corbett–I love her white-on-black trees and her Ice Haven-esque children-adults. Lilli Carre is alarmingly good at depicting male lust. Nate Neal’s not-so-instant-karma piece in Vol. 16 is explicit and haunting. Dash Shaw is a restless talent, albeit so restless he never seems to settle down even in the middle of any given strip.

But what is Mome at this point? Gone is the “recurring cast” model. Also gone is the Saturday Night Live style approach that replaced it–recurring cast featuring a couple of breakout stars with a celebrity guest each issue. Now it’s just all over the place. Here’s Gilbert Shelton’s unfunny rock epic, here’s Ray Fenwick and Archer Prewitt and Ted Stearn’s unfunny funny-animal things, here’s an astonishingly hamfisted political comic from Emile Bravo, here’s some comics from Spain that are stiff and disjointed, here’s some Conor O’Keefe stuff that’s gorgeously McKay-ian but sort of amorphous, here’s some awkwardly self-referential stuff from Laura Park and Nicholas Mahler, here’s a T. Edward Bak cover version of Dan Simmons’ The Terror and a Renee French piece that just get buried under the accumulated other, lesser contributions. I’m not sure what Mome is supposed to deliver anymore, and I’m not sure how receptive I am to whatever it is delivering.

Comics Time: Captain America: Reborn #4

November 4, 2009

Captain America: Reborn #4

Ed Brubaker, writer

Bryan Hitch, artist

Marvel, November 2009

40 pages

$3.99

In which we learn that Sharon Carter is not just the Billy Pilgriming Captain America’s “constant” in the Lost sense–she’s literally a Cap magnet, pulling him toward her through the timestream thanks to some nanotech in her blood. Ain’t Marvel Universe pseudoscience grand? That’s really all I need to get me over what reservations I had about injecting a time-displacement angle into Brubaker’s years-long top-drawer super-spy saga. And to be fair, the megastoryline kicked off with the Cosmic Cube, the wonkiest of all Marvel’s made-up tech/mystic mumbo jumbo, while one of its best scenes to date involved Bucky’s dismembered cybernetic arm springing to life and taking out a room full of SHIELD goons, so this is not without precedent. (There were some cool giant robots in there too, iirc.)

One of my favorite things about Brubaker’s run–and in this he’s been indispensably assisted by a solid stable of artists, led by Steve Epting and Mike Perkins and stood in for here by the slicker style and cantilevered action of Bryan Hitch, who in every other way is consistent with the established tone–is just how good he is at grouping various super-people together and having those groupings make visual and practical sense. Several times I’ve touted how he’s established this sort of underbelly to the Marvel Universe involving super-powered espionage-based characters: Steve Rogers, Bucky, Black Widow, Union Jack, Crossbones, Agent 13, Nick Fury and so on all look like people you really could believe take advantage of whatever relatively slight super powers they have, put on some form-fitting garb and skullcaps, and go out and assault people in classified military installations. In this issue you see some new combos in that regard, most notably a Bucky-Cap/Black Widow/Ronin trio, who are put through the paces by Hitch in a memorable hit-and-run attack in Marvel’s oft-destroyed Times Square. Elsewhere, Bru and Hitch take a trio of gaudier, more straightforwardly superheroic characters–Mister Fantastic, Hank Pym or whatever he’s calling himself now, and the Vision–and, despite this being the least naturally resonant area of the Marvel U. for Brubaker’s Cap, somehow make them click in that world as a braintrust tasked with cracking the enemy technology that’s brought Cap low.

But the best such scene–the scene that made me want to write the book in the first place–occurs when Homeland Security Commissar Norman “The Green Goblin” Osborn’s right-hand woman Victoria Hand (yup!) drags Sharon Carter, the brainwashed and disgraced Agent 13, in handcuffs into a secret lair. She looks down, and there looking back at her are Doctor Doom, the Red Skull (who’s now trapped in a robot body with a Red Skull mask and an SS uniform), racist luchadore Crossbones, Skull’s S&M daughter Sin, and the torso-themed robot Nazi mad scientist Doctor Arnim Zola. Sharon’s reaction is more bugged-out disbelief than anything else, and it’s entirely appropriate: As assembled by Brubaker, drawn by Hitch, and staged in a clever two-level set-up by the two of them, man oh man does this come across as a batshit-insane crew of lunatics. You really can’t even begin to imagine what kind of crazy horrorshow they’ve got in store for whoever’s unlucky to be dragged into that lab; it’s like the scene in Blue Velvet where Dennis Hopper forces Kyle MacLachlan into Dean Stockwell’s place, only with Doombots and time machines instead of overweight prostitutes and Roy Orbison songs.

And now that I’m writing about it, the scene reminds me in its weird, you-gotta-be-shitting-me way of a very different “here come the bad guys” reveal: that wonderful spread in the first issue of Geoff Johns and Phil Jimenez’s Infinite Crisis where you realize that Uncle Sam and the Freedom Fighters are about to get their collective bell rung by Bizarro, Zoom, Cheetah, Sinestro, Black Adam, Deathstroke, Dr. Light, Psycho-Pirate, and that DC Magneto guy Dr. Polaris–just about as fearsome an array of opposite-numbers and cool power-sets as DC can offer. But while that was prime momentism, this is like anti-momentism–the staging peels back the “whoa” factor and transforms it into a sort of wordless shudder. This is the kind of thing you want every superhero comic you read to be able to deliver.

Comics Time: Pim & Francie

November 2, 2009

Pim & Francie: The Golden Bear Days

Al Columbia, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2009

240 pages, hardcover

$28.99

At SPX this year, a friend of mine approached Al Columbia for a sketch in his themed sketchbook. Columbia started drawing, didn’t like it, tore out the page, crumpled it up. Started drawing again, didn’t like that one either, tore out the page, crumpled it up. Told my friend he couldn’t do it with all the noise and distractions in the room. Stopped drawing sketches for anyone for the rest of the day, except for a tiny circle-dot-dot-curve smiley face next to his signature for anyone who purchased a copy of this book. After I heard this story I told it to a couple of friends. One remarked that if he’d been forced to concoct a story about what trying to get a sketch from Al Columbia would be like, this would have been it. Another said he’d agree with that assessment, but only if Columbia had been paid for the work first.

Al Columbia may be the closest alternative comics has come to producing a Syd Barrett, an Axl Rose, a Sly Stone, a Kevin Shields, a sandbox-era Brian Wilson, or heck, a Steve Ditko–a prodigious, world-beating talent chased off stage by his own…ugh, I don’t want to say demons, but even if you ascribe Columbia’s Big Numbers flameout and lack of published work post-Biologic Show to perfectionism, surely perfectionism that total and unforgiving is a demon of a kind.

The genius of Pim & Francie is harnessing the power of that demon–whatever it is or was that led Columbia to abandon his impossibly immaculate conceptions of monstrousness and murder half-drawn on the page time and time again–and deploying it as a conscious aesthetic decision. Reproducing unfinished roughs, penciled-in and scribbled-out dialogue, half-inked panels, torn-up and taped-together pages, even cropping what look like finished comics so that you can’t see the whole thing, Columbia and his partners in the production of this book, Paul Baresh and Adam Grano, have produced a fractured masterpiece, a glimpse of the forbidden, an objet d’art noir. As I wrote on Robot 6 the other day:

my favorite thing about Columbia’s comics–many of which can now be found in his new Fantagraphics hardcover Pim and Francie–is how they look like the product of some doomed and demented animation studio. It’s as though a team of expert craftsmen became trapped in their office sometime during the Depression and were forgotten about for decades, reduced to inbreeding, feeding on their own dead, and making human sacrifices to the mimeograph machine, and when the authorities finally stumbled across their charnel-house lair, this stuff is what they were working on in the darkness.

The horror of Columbia’s sickly-cute Pim & Francie vignettes–a zombie story, a serial-killer story, a witch-in-the-woods story, a haunted-forest story, a trio of chase sequences–is extraordinarily effective. And the stand-alone images both inside and outside those stories–the Beast of the Apocalypse as story-book fawn, a field of horrid man-things staring right at you, a broken-down theme park and the phrase “there’s something wrong with grandpa,” a forest of crying trees, some dreadful being of black flame running full-tilt down the basement stairs, zombie Grandma stopping her dishwashing and glancing up toward where the children sleep–are as close as comics have come (hate to keep using that formulation, but there you have it) to the girls at the end of the hall in The Shining, the chalk-white face of the demon flashing at us in Father Karras’s dream in The Exorcist, the inscrutable motionlessness of characters in The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity. The craft involved in their creation is simply remarkable, with Columbia’s assuredness of line, faux-vintage aesthetic, and near-peerless use of blacks all actually gaining from his panels’ frequent extreme-close-up enlargement throughout the collection.

But moreover, these scary stories and disturbing images are all so gorgeously awful that they appear to have corrupted the book itself. They look like they’ve emerged from the ether, seared or stained themselves partly onto the pages, then burned out, or been extinguished when the nominal author shut his sketchbook and hurled it across the room or tore up the pages in terror. It’s comic book as Samara’s video from The Ring, Lemarchand’s box from Hellraiser, Abdul Alhazred’s Necronomicon from Lovecraft, the titular toy from Stephen King’s “The Monkey”–an inherently horrific object. Bravo.

Not Comics Time: Portable Grindhouse: The Lost Art of the VHS Box

October 30, 2009

Portable Grindhouse: The Lost Art of the VHS Box

Jacques Boyreau, editor

Fantagraphics, 2009

200 pages, slipcover

$19.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics, eventually

Buy it from Amazon.com eventually too

My entire circle of friends has been clamoring for this long-delayed collection of video box art for over a year–and could this be any more in my wheelhouse right now? If you made a Venn diagram out of the New Action, the Manly Movie Mamajama, and everything I talk about it that Dark Knight Strikes Again review, you’d find this right in the sweet spot. Even if this book didn’t exist, it would be necessary for me to invent it.

So let’s start by talking about what I didn’t like about it. Well, “didn’t like” is probably too strong–it’s fine, just not what I was looking for–but I couldn’t help but be let down by editor and compiler Jacques Boyreau’s introduction. You get a brief sketch of his personal history with home video, a lengthy technical history of the format, and a diatribe about the evils of digital. Actual discussion of “the lost art of the VHS box” is reserved for an interesting but meager two-paragraph rumination on the way their display in video stores made them the iconic equivalent of the films they contained, but this quickly gives way to one last swipe at DVDs, downloads, and digital projection. Nothing about any of the artists or designers involved, nothing about the evolving aesthetics of box art as home video went became a megabusiness, nothing about any of the covers on the pages that follow. If you’re looking for information about the business and creative decisions that led to the creation of this childhood-memory art form, you’ll come away disappointed.

But if you’re simply looking for a gallery of those memories and beyond, Boyreau did you right. He and designer Jacob Covery wisely chose to present the front cover of every box in the context of a product shot, rather than simply scanning the art and running it full-bleed–he’s absolutely right to argue that these images are inseparable from their status as objects. The box shots of the front cover (and spine) occupy the right-hand side of every spread, while the left-hand side reproduces the back cover. And here they do scan it and run it full-bleed, which actually just makes it funnier. Why? Well, it was clear from the start that what you needed to do with the front of your VHS box was make the image as lurid and eye-catching as possible, so there are surprisingly few variations in that regard beyond obvious budget and talent limitations in some cases. But what to do with the back cover? For a long time, no one seemed to know. The familiar tagline/teaser blurb/stills/credits framework was far from universal, and in its place were long lists of other movies released on home video by the studio (on the back of Vanishing Point, Magnetic Video Corporation listed fully fifty-eight), terse flat-affect plot summaries (The Chamber of Fear‘s blurb begins “The crevice of the volcano is very deep. Scientists are searching for a form of underground life that according to theory still exists.”), poorly written catalogues of the depraved behavior contained inside (Blood Spattered Bride notes “Although not rated this film contains nudity and scenes of graphic violence”), and in one memorable case (The Best of Burlesque–somehow I doubt it!) just a flipped and blown-up segment of the front cover’s airbrushed T&A illustration. Seeing all this proto-professional weirdness on the page normally reserved for placing the image next to it in some sort of factual context is hilarious.

But let’s face it, you’re here for the front covers, and they don’t disappoint. You’ve got titles like Drive-In Massacre, Don’t Go In the House, and Slave Girls from Beyond Infinity. You’ve got taglines like Video Violence‘s “…When renting is not enough!!”, Slashdance‘s “SAVE THE LAST DANCE…FOR HELL!” and The Lift‘s “TAKE THE STAIRS, TAKE THE STAIRS. FOR GOD’S SAKE TAKE THE STAIRS!!!” You’ve got images you likely remember from the scary sections of your local mom-and-pop video shop–the girl-gun of Master Blaster, the knife-through-the mask of Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter (the back-cover blurb appends a question mark to that increasingly inaccurate adjective, by the way), and the genuinely striking redneck cheesecake of ‘Gator Bait. You’ve got bloody knives, Giger knock-offs, urban warriors, and underboob.

As is probably clear by now (if it wasn’t already from the book’s title), the bulk of these boxes are for B-movie genre pictures. The exceptions are therefore often all the more interesting. Go Hog Wild is a glorious example of a truly lost art, the cartooned/painted high-school sex comedy poster. Barbie and the Rockers: Out of this World, with a 1987 copyright date, demonstrates the by-then astonishing moneymaking potential of the medium–a full rental fee for one 25-minute cartoon! The box-art design for Sidney Lumet’s Network, though crude by today’s standards, provides a representative look at the far classier approach to A-list studio affairs.

Most anomalous of all are the non-fiction efforts. A Johnny Bench documentary stands out for its blandness, while the Unknown Comic’s bag-clad noggin and overall awfulness could, with a little tweaking, fit right in with the various monsters and slashers. There’s a Gulf War I cash-in from ABC News, simply repackaging a military briefing from Norman Schwarzkopf. Grossest of all is an obliviously bloodthirsty hunting documentary called Bowhunting Whitetails: Just for Fun!: A grinning hunter holds a dead deer’s head by the antlers on the front, the back-cover copy revels in the hunter’s triumph over the poor stupid unarmed animal he slaughters, and there’s a tagline advertising “5 Vivid Arrow Impacts!” Even more than hilariously inept stuff like the Lon Chaney/John Carradine vehicle Alien Massacre and its crosseyed cover babe, it’s these documentaries and hobbyist videos that show just how widely the doors were thrown open to media producers and consumers of all stripes by the home video revolution.

And believe it or not, a couple of the covers even succeed as art! Boyreau smartly puts the two that do best right next to each other–the jagged ’80s splash-of-paint surrealism for the euro-slasher Eyeball (featuring an extremely rare artist credit, for illustrator Dick Bouchard) and the striking still of a loincloth-clad Cornel Wilde running from his life from spear-chucking African natives that bedecked the colonialist adventure The Naked Pray. Elsewhere, the bold two-color art for Walter Hill’s rock’n’roll fantasia Streets of Fire is ripe for reinterpretation today, I’d say; it’s easy to picture a Scott Pilgrim promotional piece riffing on its look and pose. And did I mention ‘Gator Bait? Step it up, Terry Richardson!

Now here’s the thing: A little Google Fu and you could probably come up with jpgs of nearly all the titles I’ve mentioned, and more besides. Boyreau laments how digital phased out analog when it comes to our movie viewing; has the Internet done the same with his book commemorating the losing side of that battle? I say no. It’s not just because of the tremendous job Boyreau and Covey did with the cover reproductions, or the lovely, solid paper stock, or the cutesy slipcase. It’s because Boyreau is right: the aura of the object is irreplaceable. A book collection of VHS box art contains preserves what was special about them in a way a Flickr gallery just can’t. Next time you have a trashy movie marathon, pass this around between movies–unlike your laptop, you won’t even need to worry that much about spilling beer on it.

Comics Time: The Dark Knight Strikes Again

October 29, 2009

The Dark Knight Strikes Again

Frank Miller, writer

Frank Miller & Lynn Varley, artists

DC, 2003

256 pages

$19.99

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Savage Critic(s).

Comics Time: Dark Reign: The List #7–Wolverine

October 28, 2009

Dark Reign: The List #7–Wolverine

Jason Aaron, writer

Esad Ribic, artist

Marvel, October 2009

48 pages

$3.99

Well well well, looks like Marvel decided maybe they should have strained that Grant Morrison bathwater for babies before they threw it all out. Yeah, Joss Whedon (and, in those nobly intentioned but ill-conceived Phoenix minis, Greg Pak) got to nod in New X-Men‘s direction now and then–Cassandra Nova, a one-line reference to Magneto’s trashing of Manhattan, even the Bug Room. But other than wiping out Genosha, killing Jean Grey, and establishing Emma Frost as the X-Men’s new HBIC, Marvel basically ran, not walked, away from Morrison’s ideas and tone alike. (Exhibit A: that Xorn arc from New Avengers.) So writer Jason Aaron’s full-fledged Morrison Marvel Team-Up in this very very central event title, pitting Wolverine, Marvel Boy (!), and Fantomex (!!!) against Norman Osborn for the fate of The World (i.e. the Morrison-created birthplace of the Weapon Plus program that spawned everyone from Captain America to the ol’ Canucklehead), is something of a turning point. Certainly I didn’t expect to see a French-accented international man of mystery playing a role in Dark Reign, except perhaps as someone for Ares to chop in half in a throwaway sequence in Dark Avengers.

What’s impressive about this is that rather than try to ape high Morrisonian “mad ideas” (except for a played-for-laughs viral-religion thing), Aaron riffs on an entirely different Morrison tone: cheeky high-concept comedy. Instead of writing Marvel Boy as some sort of brooding military brat, Aaron returns him to the quasi-Clockwork Orange blend of arrogance, ultraviolence, and killer good looks that made his original Morrison miniseries such a hoot. He’s like Chuck Bass with insect DNA. (Okay, more insect DNA.) Similarly, Fantomex is treated as a charming rogue with a cool white uniform rather than Aaron simply waving his hands in the face of his weird power set and Frenchness and giving up or phoning in some black-ops boilerplate. Wolverine actually plays a supporting role more than anything else, but when he’s unleashed, it’s in a splatstick fashion consistent with the joli-laid physicality Morrison’s collaborator Frank Quitely imbued him with. Ribic’s art goes a long way in this regard–I’d previously known him only for his admittedly dynamic Alex Ross-indebted painted work, but his pencils have a cartoony zest that would be right at home on some three-issue Vertigo miniseries.

What does it all mean in the context of Dark Reign and The List and so on? As best I can tell, not much. But reintegrating Morrison’s many toys into the mainstream Marvel Universe, as opposed to the province of editorially hands-off limited series, is pretty momentous in and of itself. Fingers crossed we’ll see the Phoenix Corps again when all is said and done.

Comics Time: nothin’

October 26, 2009Today’s Comics Time review has been canceled because I accidentally read and reviewed a book that’s embargoed until Wednesday. I am a doofus. Comics Time will resume on Wednesday, and I may throw in an extra review at some point this week just to make up for this. You never know.

Comics Time: Invincible Iron Man #19

October 23, 2009

Invincible Iron Man #19

Matt Fraction, writer

Salvador Larroca, artist

Marvel, October 2009

40 pages

$3.99

It’s been a long time since I read superhero comic that wasn’t by Grant Morrison more than once out of enthusiasm rather than confusion. But golly, I enjoyed this one, and I enjoyed it just as much the second time around.

Subtitled (somewhat pretentiously) “Into the White (Einstein on the Beach),” this is the conclusion of the year-long “World’s Most Wanted” arc of Fraction and Larroca’s movie-toned Iron Man book, in which the disgraced and deposed Tony Stark runs around the world trying to destroy both his tech and his own mind lest both fall into the hands of new King Shit of Turd Mountain Norman Osborn. In the past I’ve found this set-up very hard to swallow because of how dependent it is on other, lesser comics like Civil War and Secret Invasion. For example, I don’t care what universe you live in, if Bernard Kerik can go from Homeland Security chief nominee to getting his mugshot taken, it strains credulity that a guy who used to dress up as a goblin and throw pumpkin bombs at people is gonna get put in charge of jack shit.

But Fraction compensates for this inherited conceptual sloppiness simply by making the plot mechanics for this story as tight as he possibly can. He cuts relentlessly back and forth between the protagonists and antagonists: the Charlie’s Angels trio of Black Widow, Maria Hill, and Pepper Potts attempting to escape from Osborn’s lair; Osborn’s second-in-command Victoria Hand trying to prevent this and quaking in terror of what will happen if she doesn’t; Osborn himself cockily closing in on his quarry; the intelligence-officer grunt who’s secretly feeding Osborn bad information and the colleague who smells something fishy about him; and Iron Man himself, experiencing an Algernon-like loss of his faculties as he hurls himself in his dilapidated old armor toward his final destination. If you’ve ever tried to write an action sequence, let alone cross-cut between several of them, you know how hard it is to get what needs to happen to happen for any reason other than your need for it to happen, right? Well, never once do the A-B-C sequencings of Fraction’s various plots feel like they’ve skipped a letter just to get to point Z quicker. From the captured spies moving up and down and in an out of an elevator, to the precise interpersonal dynamics between all the personnel involved in Norman’s pursuit of Tony Stark, each moment proceeds directly from the last, whether physically or emotionally.

How many fight scenes have you read lately where a character will get smacked several dozen yards by some giant powerhouse only to be up and about a few pages later? How many times have creators had to go online to clarify the physical fate of a character whose beating they wrote into incomprehensibility? How many times has a climactic battle been undercut completely by glib banter, almost completely disconnected from the circumstances of that place, that moment, those characters? You’re not gonna get any of that shit here. Each scene and sequence feels like it’s taking place in a physical space you and the characters could navigate, with physical maneuvers having readily understandable physical consequences. Each move toward and away from the characters’ goals comes with a sense of the stakes involved–the grand illusion of serialized shared-universe superhero storytelling, that there really can be winners and losers, has rarely been so astutely conveyed.

This is all the result of what feels like a real partnership. This issue’s success is equally due to Fraction’s just-right dialogue and direction and Larroca’s deft work with body language and fight choreography. (His days as a Greg Land-style spot-the-photoref novelty act are loooooong behind him.) Both shine brightest in the climax, making Osborn’s slide from glee to rage to frustration to confusion to defeat snatched from the jaws of victory as clear as day and almost frightening. It’s capped off with a one-liner in which the totality of Tony’s pwnage of Norma is made hilariously clear (provided you’re a Marvel nerd), and a one-page coda that manages to set up the coming mega-crossover without losing a sense of beatific victory and loss.

Did I mention that they managed to rehabilitate Iron Man’s badly damaged character in my head, despite the fact that even now none of his actions during Civil War have turned out to make any kind of practical or moral sense within the world of the story in any way? And that they managed to establish Spider-Man villain the Green Goblin as a for-the-ages Iron Man enemy as surely as Frank Miller made Kingpin the archnemesis for Daredevil? I dunno, man, this is some mightily effective work in this genre. I feel like it should be taken apart and studied at story summits for a long, long time: If this is what you want to do, this is how you want to do it. Aw, hell, I’m gonna read it again.

Comics Time: Slow Storm

October 21, 2009

Slow Storm

Danica Novgorodoff, writer/artist

First Second, 2008

176 pages

$17.95

This is like half of a good book. The visual half, for the most part. Danica Novgorodoff’s story of a Kentucky firefighter and the undocumented Mexican worker she kinda sorta befriends after a fire claims the stable he tended is a stunning-looking thing. She has a wiry line that often suggests handwriting, with all its idiosyncracies, so that the occasional wonky scale or perspective seems like (or can be passed off as) a deliberate choice. Individual moments beam out a little Taiyo Matsumoto, a little Ralph Steadman, a little Gerald Scarfe, only with the dial turned from savage to lilting. And her watercolor coloring takes a limited palette of greens, browns, grays, and oranges and fleshes out the artwork so lushly I barely even realized just how few colors she limited herself to in the first place. It’s in the moments where she really draws with the colors–a creek, a tornado, the omnipresent cloud and fire motifs–that the book comes alive.

But its in moments where the dialogue takes the lead where it sputters. Frequently too portentous–every conversation creaks under the weight of capital-M Meaning–it fails to convince us of firefighter Ursa’s shattered psyche, so that when she perform’s the book’s central act it feels like a horrifying, selfish overreaction. Which, granted, it’s supposed to feel like, but you’re also supposed to think “okay, I could see where that came from,” whereas I just thought “Christ, what a fucking maniac.” Ditto her behavior during the event’s fallout, which adds “asshole” to the equation. Meanwhile, Rafi, the Mexican immigrant, is laden with poetic visions of saints and white horses–it’s just laid on too thick. The key for Novgorodoff (an Isotope winner and Eisner nominee who clearly doesn’t need any advice from me but what the hey) will be to scale back her swing as a writer and tell a story as understated as her art is sweeping.

Comics Time: Driven by Lemons

October 19, 2009

Driven by Lemons

Joshua W. Cotter, writer/artist

AdHouse, September 2009

104 pages, hardcover

$19.95

Buy it from AdHouse, eventually

So yeah, this is pretty much the ideal Josh Cotter comic for me. Didja like the bizarre, symbol-laden wordless reveries of Skyscrapers of the Midwest? Here’s a whole book full of them! This shit makes the locust/migraine sequence from Skyscrapers #2 look like Dilbert! What’s it about? In large part, who cares? Like (in my experience) most great comics, it’s about how, and what, it makes you feel. It makes me feel like one of those ’80s special-effects sequence where some being’s exterior shell is chipping away and beneath each chunk that falls off a blindingly bright white light shines out like a beam–like that’s basically what Cotter did to his own brain to produce this thing, and like that’s what you run the risk of if you stare too long.

That’s essentially what Cotter does, visually, over and over again throughout the book: Something will cause one of Cotter’s nominal protagonists (anthropomorphized Life in Hell bunnies, pretty much) to spew forth from his person an amount of visual information that totally overwhelms them and the page itself, scribbled and scribed like a Charles Crumb notebook, and at one memorable point caked/painted with watercolors squeezed straight from the tube. In that light, and considering the first section’s apparent Chicago setting and slow evolution into comics from a straightforward-ish stream-of-consciousness prose-plus-doodles diary format, it’s tempting to read the book as some sort of autobiography: a story of the onset of, treatment of, and recovery from mental illness. For what it’s worth, I interviewed Cotter about his life and work at length for The Comics Journal and such an incident never came up, though I could have just whiffed on it. If I’m wrong, so much the better for Cotter, because having dealt with the mental-health institutionalization of two people very very close to me, this is about as accurate a representation of what I always pictured going on in their heads as you’re gonna find. Noise, blotting out signals and forming its own.

Glorious noise, too. For all of the books insular inscrutability, several passages here stand out with an effect as awe-inspiring as a great visual effects sequence in a blockbuster by some genuine Hollywood visionary. The paint explosion. The great cloud of scribble, with sensuously tangled lines looking like they’ve somehow been carved through other lines. The marvelously reproduced, bright reds and blues representing warring states of mind, popping off the off-white pages like 3-D. (The whole book, a facsimile of Cotter’s sketchbook, is really an astonishing work of design by Cotter and Chris Pitzer.) The forward momentum of the chase sequence, with two bunnies battling for supremacy in frame after Haring/Muybridge mash-up frame. An eruption of a column of red that rockets into the sky so powerfully you can practically hear the noise. And a creepy cameo by the mad god Dionysus, quoting the soundtrack from the animated Transformers movie, rings out as a reminder of madness after all is said and done like that dissonant shot of the cab’s rear view mirror at the end of Taxi Driver.

Outstanding work. Where the hell does he go from here?

Comics Time: Abstract Comics

October 16, 2009

Abstract Comics

Andrei Molotiu, editor

R. Crumb, Victor Moscoso, Spyros Horemis, Jeff Zenick, Bill Shutt, Patrick McDonnell, Mark Badger, Benoit Joly, Bill Boichel, Gary Panter, Damien Jay, Ibn al Rabin, Lewis Trondheim, Andy Bleck, Mark Staff Brandl, Andrei Molotiu, Anders Pearson, Derik Badman, Grant Thomas, Casey Camp, Henrik Rehr, James Kochalka, John Hankiewciz, Mike Gestiv, J.R. Williams, Blaise Larmee, Warren Craghead III, Janusz Jaworski, Richard Hahn, Geoff Grogan, Panayiotis Terzis, Mark Gonyea, Greg Shaw, Alexey Sokolin, Jason Overby, Bruno Schaub, Draw, Jason T. Miles, Elijah Brubaker, Noah Berlatsky, Tim Gaze, Troylloyd, Billy Mavreas, writers/artists

Fantagraphics, 2009

232 pages, hardcover

$39.99

Visit the Abstract Comics blog

One of the pleasures inherent in anthologies is the way proximity draws out the contrast between successful and unsuccessful work. One of the unique pleasures of this anthology is how that success or lack thereof can be determined not just by the subjective standards of the reader but also by the ostensibly objective standards of the anthology itself. In his introduction, editor Andrei Molotiu defines abstract comics thusly:

What does not fit under this definition are comics that tell straightforward stories in captions and speech balloons while abstracting their imagery either into vaguely human shapes, or even into triangles and squares. In such cases, the images are not different in kind, but only in degree, from the cartoony simplification of, say, Carl Barks’ ducks….While in painting the term [“abstract”] applies to the lack of represented objects in favor of an emphasis on form, we can say that in comics it additionally applies to the lack of a narrative excuse to string panels together, in favor of an increased emphasis on the formal elements of comics that, even in the absence of a (verbal) story, can create a feeling of sequential drive, the sheer rhythm of narrative, or the rise and fall of a story arc.

True, none of the comics featured here use (legible) captions or speech balloons. But as Molotiu’s subsequent emphasis on “images” implies, the lack of text is incidental to the more fundamental lack of narrative or story. It’s by that petard that several of the strips Molotiu selects are hoisted. The contributions from Ibn Al Rabin, Lewis Trondheim, Andy Bleck, and to an extent Mike Gestiv and Bill Shut all rely precisely the sort of “difference in degree” Molotiu warns about–in their comics, abstracted shapes perform actions based on recognizable, and in some cases quite clearly depicted, physical motivations and even emotions, just like the “triangles and squares” we’re told may as well be Uncle Scrooge. These strips are cute, but not exactly challenging, and far from abstract.

But the successful strips in Abstract Comics prove that comics need not depict emotions to pack an emotional wallop. Indeed, part of my long-held enthusiasm for this project stemmed from my suspicion, based on steps (small and giant alike) in the direction of abstraction during this decade by such alternative comics artists as Kevin Huizenga, John Hankiewicz, Anders Nilsen, Josh Cotter, and Frank Santoro, that abstract comics stripped completely away from their narrative moorings–abstract comics “in the wild,” as it were–had the potential to generate emotional content of enormous power. What I didn’t expect was just how…I don’t know, idiosyncratic my reaction to such comics would be.

For example, I’ve already described how the more openly narrative works contained here elicited a chuckle but not much else. What’s interesting to me is how the sorts of shapes used by those artists–outlined blobs, for the most part–left me cold even in purely abstracted form. The squiggles of Elijah Brubaker, the whorls of James Kochalka, suggest a warmth and an airiness I’m just not tuned into at all. I’m not a curve man, it turns out. Meanwhile, I’m equally unaffected by strips that eschew drawing sharp contrasts from image to image and panel to panel, either by muting the differences between juxtaposed visuals (Warren Craghead, Richard Hahn, Janusa Jaworski) or by weakening or eliminating the parametric framing and structure provided by panels (Noah Berlatsky, Billy Mavreas, Troylloyd, Tim Gaze, Bruno Schaub).

What I am interested in, it appears, are angles. boxes, cold geometry. Jason Overby’s “Apophenia” is perhaps my favorite comic in the whole book: Beginning with a grid of penciled-in panel borders containing nothing at all, it proceeds to flash various sharply carved shapes into panels at random intervals like sudden words emerging from a haze of silent static, or subliminal messages erupting from a blank screen. Mark Goneya’s “Squares in Squares” is just that, panel after panel of brightly colored squares surrounding one another like an infinite regression, their position within the panel shifting slightly to slow our eye’s descent into the abyss. Mutts creator Patrick McDonnell’s untitled, college-vintage contribution uses a repeated bisected-circle motif in black, white, and watercolor-blood red to suggest cold sunrises and magisterial eclipses. And Spyros Horemis black-and-white concentric circles and swirls practically glow off the page with the force of an optical illusion.

I’m also interested in a sense of awe and scale. Molotiu’s own excerpts from The Cave overwhelm with bright colors and massive slopes that dwarf panel borders and seem to escape his control, like a microscopic process blown up to IMAX size or a projected filmstrip set on fire. Henrik Rehr’s “The Storm” is as aptly named as was “Squares in Squares”: Great waves or windgusts toss us to and fro across black backgrounds, sending tiny offset panels scattering like leaves. Alexey Sokolin’s “Life, Interwoven” sees its panels slowly overwhelmed by furious black scribbling, like a diary of a madman, until it not only totally blots out the grid but appears to topple it over.

And sometimes I’m like John Cleese’s pope: I may not know art, but I know what I like. I like the loneliness of Blaise Larmee’s tiny, shaky, frail, incomplete rectangles against their off-white background in his Nilsenesque “I Would Like to Live There.” I like the humor of Geoff Grogan repeating a bullseye motif until the laugh-out-loud punchline photo of a woman’s nipple in “Bullseye.” I like Jason T. Miles creating shapes out of chunky, semi-monstrous black and white lattices–Brinkman Blocks, if you will–then signing it with a great big clumsy JASON T. MILES in “Mainstream Blackout.” I like the implied sequentiality of Mark Badger following up a pencil-sketched “Kung Fu” strip from 1980 with a boldly colored remake of the same strip from 2008. And I like the pure psychedelia–in the information-overload sense–in R. Crumb’s “Abstract Expressionist Ultra Super Modernistic Comics,” drawn, laid out, and even titled as though attempting to get it down on paper winded him.

So. By my count I liked, mmm, about half the book, give or take a couple strips. And there are potentially fruitful paths that remain largely untrodden. For example, I know Molotiu has been doing yeoman’s work on carving out a space for nonnarrative comics for years because I remember jostling with him a bit about on the Comics Journal messageboard following the release of Kramers Ergot 4 in 2003; however, the work of Fort Thunder and its fellow travelers, showcased so memorably in Sammy Harkham’s anthology, isn’t represented here (unless you count their spiritual godfather Gary Panter). Meanwhile, Crumb and Larry Zenick excepted, the use of representative figures in an abstract way is elided here; I wish Molotiu had selected one of John Hankiewicz’s enormously effective strips in this style rather than the comparatively staid and painterly contribution we see here. And for my money, the sequencing peters out toward the end–I’m not sure what I was supposed to take away from the final strips, rather formless black and white affairs. An editorial focus not so much tighter as tweaked, I suppose, is what I’m looking for.

But what I liked! What I liked, I liked for more than just the strips themselves–I liked them for the proof they offer that comics really is still a Wild West medium in which one’s bliss can be followed even beyond the boundaries of what many or even most readers would care to define as “comics.” That an entire deluxe hardcover collection of such comics now exists is, I think, one of the great triumphs for the medium in a decade full to bursting with them. And even if the book’s existence is ultimately more impressive than the sum total of its contents, it strikes me as churlish to complain.

Comics Time: Sulk Vol. 3: The Kind of Strength That Comes from Madness

October 14, 2009

Sulk Vol. 3: The Kind of Strength That Comes from Madness

Jeffrey Brown, writer/artist

Top Shelf, September 2009

64 pages

$6

I still don’t get where this whole “Jeffrey Brown can’t draw” thing comes from. I mean sure, if your standard for artistic excellence is Neal Adams or something, you’re gonna be like WTF, but as always I’m ignoring those people and talking about altcomix fans who should know better. I’ve said this before, but compare the work of Brown (full disclosure: I like him a lot personally) to that of any of the ultra-lo-fi slice-of-life humor/pathos diarists who’ve emerged in his wake and he’s just doing so much more–with how he arranges space in his panels; with how he adds line upon line for shading, depth, and detail; with the expressiveness of his characters; with how even his action pastiches are genuinely dynamic and fun to follow; with how he bounces from genre to genre with the same “here’s something I thought was funny about this topic” good humor. Especially in the outright humor stuff, he’s like your funny friend bullshitting.

That’s not necessarily to say that everything he does is for everyone. As in previous genre-parody works like Incredible Change-Bots, the sci-fi/action/fantasy hodgepodge of Sulk #3 presupposes simultaneous knowledge of, affection for, and skepticism of the kinds of stuff he’s swiping from/at, plus (obviously) an appreciation of Brown’s visual approach to the material. It’s an acquired taste: The ribbing might be too gentle for people who wanna see an indie stalwart get some yuks at the expense of elves and unicorns, while the irony might be tough to stomach for po-faced “new action” fans. Indeed I think the reason why Brown’s Bighead books (including Sulk #1) are the strongest of his work in this area is because this kind of parody is more familiar with superheroes than with any other subgenre; you can “get it” easier than you can when you’re dealing with pirates or D&D or Godzilla or boy geniuses as you are here. Meanwhile the MMA-based Sulk #2’s 80-page fight scene was easy to grok as an exercise in ways drawing combat and writing the combatants’ interior monologues. The anchor point in The Kind of Strength That Comes from Madness is much harder to locate.

I suppose it just comes down to what you think you might want to see in a comic. Do you want to see an adorable, realistically depicted stag smack his antlers against a tree and then stare at the reader, demanding to know “DO YOU STILL WANT TO TANGLE WITH ME?” in giant capital letters? Do you want a ground-eye-view parallel to Brown’s memorably poetic giant-monster rampage comic from Mome in which a couple of moron brothers take the opportunity to make a “looting list” out of their weekly grocery list and then smack the dying reptile around with a baseball bat? Do you want to read lines like “A vampyre! It’s exactly like a vampire, but far more dangerous,” or hear small-city residents thank goodness that the giant monster is attacking their town instead of big important places like New York or L.A.? Do you want the occasional visual digression about boobs or beards or babies? I know my answers at least.

Comics Time: Cold Heat #7/8

October 12, 2009

Cold Heat #7/8

BJ & Frank Santoro, writers

Frank Santoro, artist

PictureBox, September 2009

48 pages

$20 (hey, it’s a limited edition of 100)

Radiohead threw me not when they made their shift into electronic music with Kid A–I’d been listening to Aphex Twin since I was a sophomore in high school, yeah that’s right, I’m an IDM OG, or at least as close as we got to one on L.I.–but with the two albums after that, Amnesiac and Hail to the Thief. I now listen the heck out of those records (okay, more Hail than Amnesiac), but the band’s sudden lack of interest in providing the big, sweeping, soaring moments of catharsis they were still doing as late as “How to Disappear Completely” and “Morning Bell” struck me then and now as a willful avoidance of their own strengths. Now they’re doing that sort of stuff again on In Rainbows and all is well with the world, but I do wish that more people would acknowledge that guitar rock or no guitar rock, that was the big, not-entirely-successful risk they took this decade.

Something similar is going on in Cold Heat #7/8. For about 4/5ths of this limited-edition double-issue installment of Santoro & Jones’s punk-rock sci-fi saga, the psychedelic vistas and geometric reveries that were the series’ aesthetic calling card are largely abandoned. In their place is a comparatively straightforward, albeit tongue-in-cheek, international espionage quasi-parody involving cynical jetsetting journalists, deadpan quip-dropping CIA agents, sinister pharmaceutical conglomerates, crooked conspiring politicians, and Castle, the small-town American fuck-up who’s unwittingly unravelling the plot. Silence is rare, with more voluminous dialogue and lots of those little labels Santoro likes to drop in. It’s the sort of thing some combination of Stephen Soderbergh, George Clooney, and Matt Damon might release in a limited September theatrical run, or what you might see in one of the Coen Brothers’ seriocomic conspiracy-caper flicks if they were given an effects budget and asked to throw something spacey in there now and then. There’s even some broad comedy about the U.K. rock press and a celestial poker game involving not-exactly-dead rock star Joel Cannon being invited to play a hand with Jimi, Janis, Jim, and John. (Jerry opted to kick it in the hot tub.)

This ain’t your father’s Cold Heat, long story short. Honestly it’s so different in tone it feels more like a particularly off-model Cold Heat Special than a Cold Heat proper. And it may not be the droids you’re looking for–at least until the very end, where Castle searches for her kidnapped journalist lover, running through the streets of Rio in a wet bathing suit, fleeing the psychic and physical attacks of the evil Senator Wastmor’s puppetmasters. That’s the sort of dreamlike/nightmarish imagery you’ve come to expect from Cold Heat, and it’ll be interesting to see if there’s more of that in the offing, perhaps wedded to the new potboiler-parody structure we’re seeing here. Here’s hopin’.

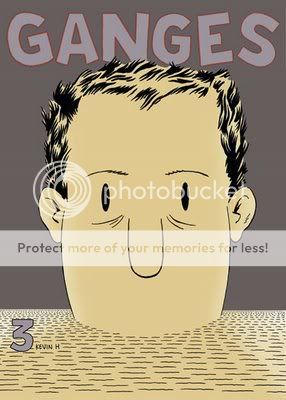

Comics Time: Ganges #3

October 9, 2009

Ganges #3

Kevin Huizenga, writer/artist

Fantagraphics/Coconino, September 2009

32 pages

$7.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics, eventually

You wanna talk about a gateway comic? How ’bout handing this sucker to anyone who’s ever had trouble falling asleep? The whole thing is dedicated to nothing more or less than reproducing the mental and physical sensations of insomnia. Ironically it’s Huizenga’s most action-driven comic this side of Fight or Run or the video-game bits in Ganges #2. In order to evoke the insomniac mind’s uncontrollable wanderings, Huizenga takes Glenn Ganges’s mental avatar and sends him on a series of Cave-In-like explorations–dipping him into water, sucking him down the drain, walking him up a tree, bouncing him off thought balloons, floating him along on sleep bubbles. At one point he mentally fends off invisible burglars; at another he’s armed with a bow and arrow, or a machine gun, taking aim at his own wiredness. Combine it with one of the most effective uses yet of the Ignatz series’ two-tone color palette–here a cool small-hours blue–and the experience is almost tactile, as though you’re physically tunneling through the mysteries of your own mind. It’s only when Glenn finally gives up and gets out of bed that the gutters switch from black to white and everything instantly feels less dense, less close; naturally, removed from the million-miles-a-second flow of his Glenn’s thoughts and reset in the real world, the action switches from complex reverie to straightforward cutesy business involving playing music late at night and freaking out when the cops show up about the noise. The mastery of tone is deeply impressive.

Look, I’m always gonna be up front about how I think the “Gloriana” issue of Or Else, #2, is the best thing Huizenga’s ever done. That thing hit me with the force of a revelation, and so I tend to be deaf to the claim that he keeps getting better and better. (Particularly regarding Ganges #1 and its disastrously wrong take on the Beatles’ “She’s Leaving Home”!!!!!!1!!111!) That’s as good as he’s gotten. But it’s obviously true that each new release proves just how much he’s mastered the stuff of comics, and how thoroughly he’s staked his claim on chronicling areas of contemporary American human experience few if any other cartoonists are going anywhere near. It’s pretty darned exciting.