Posts Tagged ‘Abercrombie & Fitch’

Sex, Lies, and Cheap Cologne: An Oral History of Abecrombie & Fitche’s Softcore Porn Mag

August 31, 2020After that, I was like, “Holy shit, there are no limits.”

I contributed to an oral history of the Abercrombie & Fitch Quarterly by MEL Magazine’s Isabelle Kohn. Weird job, great times, fun article!

Phoebe Gloeckner Interviewed, 2003

March 19, 2013On April 24, 2003 I interviewed Phoebe Gloeckner, cartoonist and author of A Child’s Life and Other Stories and The Diary of a Teenage Girl, for Abercrombie & Fitch’s “lifestyle publication” A&F Quarterly. Within a few months the mag was shuttered and the interview never ran. I just noticed that it also didn’t survive the move from my old blog to this one. Now that word is out that playwright Marielle Heller is directing a film adaptation of the book, I thought it would be a good time to repost it.

This is a pretty raw, conversational thing — it would have been edited very heavily for space, but back then I always asked a ton of questions I knew wouldn’t end up running in the finished piece, just because I was curious about the answers. I broke it up into sections for ease of reading.

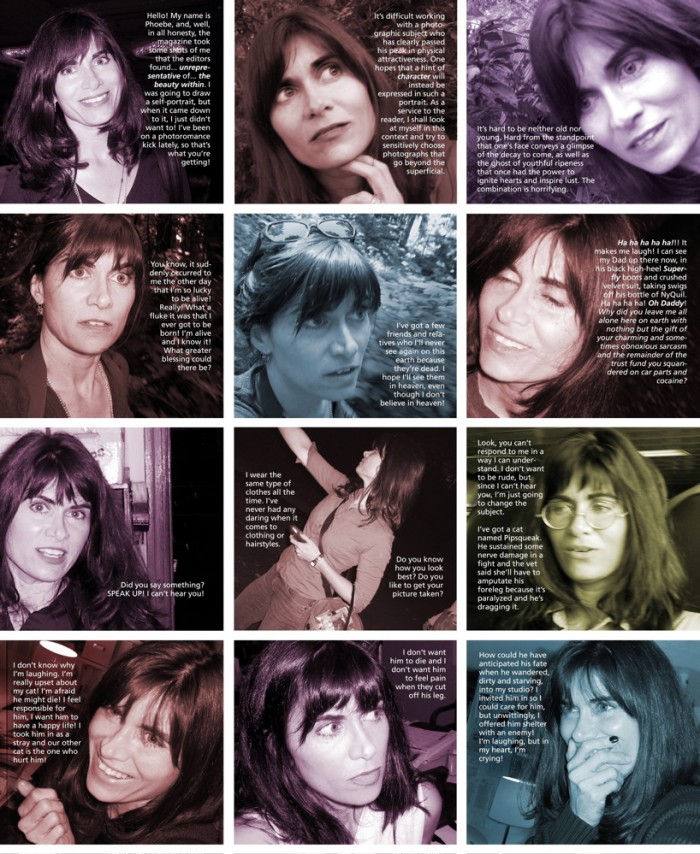

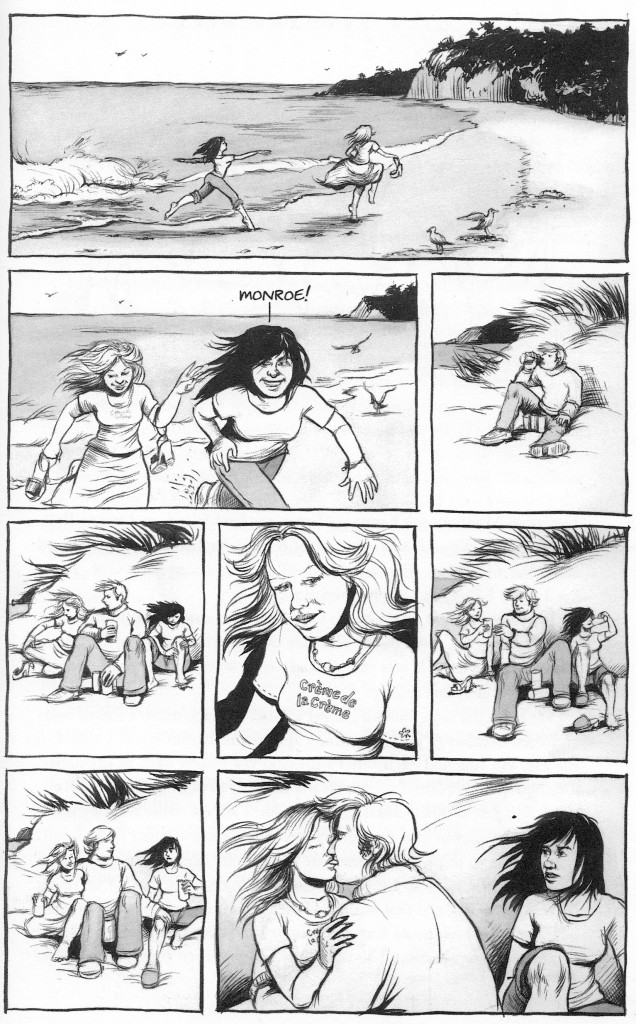

It’s bookended with a photoessay Phoebe made to accompany the piece after none of us liked the photos we had taken of her (“I felt like a drag queen” was her take on them) and a page from Diary that may be my single favorite comics page of all time.

Autobiography?

SEAN T. COLLINS:I’ll start with this question, because I know you’ve answered it a million times–

PHOEBE GLOECKNER: It’s not about me. Is that what you were gonna say?

There you go! Well, you’re reluctant to classify your work as autobiographical. I know you’ve talked about it a billion times, but I figured I’d ask for our readers who may not know your work already: Why is that?

I am an empty shell of a person, I don’t have any personality, and I can fake it in my character. Okay? It’s not me. I don’t know what to say. I don’t think my work is any more autobiographical than anyone else’s work. I think–really, for the human being, there is no such thing as truth. I mean, there is no such thing as veracity. It just sounds like existential bullshit that I’m saying, but I really think it’s true. I would never claim to understand anything, much less be able to recite the truth about anything or any event that I witnessed. So what does autobiography mean? I think it’s a misnomer. I don’t think there is any such thing. I mean–history: What is history? You know? It’s one person’s or a group of persons’ perspective on things that happen. You know, I’ve talked about this so much–

I know. You’ve gotta be sick of it by now, too, huh?

Yeah, yeah. (sighing)

Do you think you get asked it more because you’re a woman?

I don’t know. Why are you asking me?

I figured it would be interesting to–

–to hear the same answer again?

Well, because the people who read the A&F Quarterly probably haven’t heard it before, you know what I mean?

Oh yeah. Well, did you ask that guy David Amsden? (author of Important Things That Don’t Matter, shot earlier in the same studio where we shot Phoebe–ed.) Did you ask him if his story was true?

I didn’t interview him.

Why not?

Because someone else did.

Ok, so did they ask him if his work was —

I don’t know. I’ve been trying to think about this, because–

Ok, your wife. You said she read my book or something?

Yeah.

Ok, did you guys ever talk about whether it was true or not?

Mm-hmm.

And what was your conclusion? Is it true?

I guess that’s what we thought.

Or you assumed?

Right, right. I mean, from your point of view.

Right. So you think I’m Minnie, me?

You look a lot alike.

(laughs) No, but–so that’s what you think? You think I’m Minnie?

I guess so. Man, you are totally turning the tables on me.

(Both laugh)

well, no. but I really don’t understand what other people think. I don’t experience my work the way other people experience it. I mean, I don’t wonder as I’m working on something if this is about me or not. It doesn’t enter my head.

Obviously, people say that everything that a given artist does is autobiographical in some way.

Right.

You know–you don’t just pull it out of the sky.

That’s what always say. That’s my word.

It’s always relevant to you in some way. And people who write fiction that’s never mistaken for anything but fiction work in scenes from their own life or conversations that they had.

Woody Allen. I mean, is everything true? It’s not a matter of true or not. Any way it’s so bull–Look, if I said it were true, my mother would put me in jail, so even if it is true I can’t say so. My mother–yeah–um– in that sense, yeah, I am Minnie. I’m this little teenager, middle-aged teenager under the thumb of my mother. And I’m scared.

Well, that’s not what I meant.

Oh, okay.

I just meant you were that at one point. Maybe.

Oh, yeah.

I think part of what makes people ask is that it’s rough stuff. I think people glom on to stories about prisoners of war, or people who survive bad car accidents or natural disasters or shoot-outs and bank robbery or whatever. Survivor stories.

Yeah.

And you want to know what’s going on, since a lot of the material is upsetting.

Look, give me anybody’s life, I can make a car wreck out of it. I mean, who doesn’t have a car wreck? Does it seem sensational or something?

No, it’s doesn’t sensationalize. It’s doesn’t have this “Oh, woe is me feel” nor “you bastards who did mean things to Minnie.” It doesn’t have a lot of self-pity, and not a lot of condemnation either. Is that how you would look at it?

(pause) Sorry, I’m just thinking. No, I’m a person who is generally full of hatred and venom. Honestly. And vindictiveness. And full of resentments of all sorts. But yet, I feel like it’s always giving me power. That’s a source of energy for me. I like feeling mad. And if it doesn’t come out in my books, I don’t know why.

When you’re writing or drawing, are you pissed off?

Yeah, sometimes. But I’m also–I’ve never felt sorry for myself, though. But now I’m talking about myself as though I’m that character, which of course I’m not. I think anybody in their life is drawn to experience. Some people are afraid of it, but they wanna go close to it. Maybe that’s what the fascination is with reading books like this or about car wrecks or prisoners of war–because people are drawn towards experience. And so anyway the teenager in this book, in a sense, is very innocent. And she’s just in a situation where the adults around her aren’t really looking out for her best interests. But she goes along with it because basically she doesn’t know any better, and like any teenager she wants experience. But unfortunately she’s not with a group of other teenagers her age, and they’re not doing normal kid things. But I think it’s basically situational, because I think in a lot of ways she’s just a typical teenager in that sense. They don’t think they’re ever gonna die, they wanna try everything, find out who they are, see where they fit in the world.

Do you hear from people who are in similar situations?

Yeah. And people who aren’t too.

Was than an intention of yours when you set about doing this?

No. I don’t know why I feel like such a, um, bad person to interview. I mean, my experience, when I’m doing a comic or a book or something, is totally solitary. I hate telling people what I’m working on. I hate sharing it and running it by people. I’m just not that type of artist. A lot of people, cartoonists I know, they are collaborative and they like to talk about their work and run things by other people. I’m just not like that. My experience of it–I get totally–I mean in a way Minnie is me, because when I’m drawing a character or writing a character’s part I totally feel it. I get real upset. I get angry (laughs). If I’m drawing somebody else–there’s a character named Monroe, and if I’m drawing him, I find myself making the expressions that I’m drawing. I’m trying to feel like this sloppy drunk. Whatever I’m doing, whatever person I’m trying to give a voice to, I get really into it. I don’t know–I always assumed that everyone had that experience when they’re creating art. But when I describe my process or when I describe how I think Minnie is not really me and this thing about the truth–either I’m explaining myself very poorly or I have a very different experience of creating a story than other people do, and I just don’t get that. But that’s happened to me a lot. I know a lot of times I feel a certain way, and people are surprised, and I don’t understand what the hell they’re surprised about. So, I’m never quite sure, you know?

The politics of comics; Girls on film

(pause –Phoebe looks at Sean’s notes)

What’s this about a ghetto?

Ah, there we go! Thank you for giving me a transition! The “Women in Comics” Ghetto.

(pause)

Who are they?

No –it’s just that–

I told you, I don’t wanna be a girl, I don’t wanna be female. Just think of me as one of the guys. You can be a chick.

But that’s what I’m saying. My hunch is that people often approach your work as, “We’re gonna do an article and it’s gonna be Phoebe Gloeckner and Debbie Dreschler and Trina Robbins, etc.” And it’s, like, “Women in Comics,” whereas it’s not gonna be “Men in Comics” with Dan Clowes–

Right. I think, in my heart of hearts –I might sound like an asshole–but I think that my drawing or my stories are as good as many male cartoonists.

They are.

However, I’m never included in anything–

I’ll put it to you this way. The reason I started reading your stuff is because I was working on a comic about a teenage girl, and I was like, “Let’s see what other people have done about it.” And I was pissed that it had taken me so long to find your work. I was pissed that people aren’t talking about you.

I’m totally ignored.

Yeah, and I really–Now I’m gonna sound like an ass-kisser, which I’m not trying to be. But if you’re weren’t as good as you were, I wouldn’t be as pissed. I think this (taps on copy of Diary of a Teenage Girl) is every bit as good as Acme orEightball or whatever. And why isn’t this, y’know– I was really irritated.

No, I’m really irritated too, to tell you the truth, but I’m an irritable person, like I said. So I don’t know how much of it is me doing the sour grapes thing. I’m a very hard worker and I feel like I generally try to do my best. I’m just talking about my work ethic. Yeah, I’m largely ignored. Totally ignored. I had this big break: Someone interviewed me for the New York Times Magazine. Two years ago. And it was someone outside of comics who just happened to find my work. Okay, basically, that was it. It was a fluke, an accident. And I feel really fortunate though, because–(pause) Now I’m at a loss for words. I think it’s so complicated. I do feel kinda –wait. Don’t listen to me–What am I saying? How do I feel? I wonder. I don’t know. I wish you could tell me. How much of is it because I’m a woman that I’m ignored? Or maybe people just don’t like the stories. Maybe they don’t like the subject matter. Maybe they just don’t like it. Maybe they don’t like my drawings. I mean, The Comics Journal’s never interviewed me.

There’s only so much I could go into the politics of comics.

But I wish you could tell me, not even in print. ‘Cause I don’t get it. ‘Cause they interviewed everybody, people who have hardly done anything, and I’ve been around for a long time.

I really don’t understand it. I feel like a project like Diary of a Teenage Girl, because there’s prose in it–where do they put it in a bookstore? Like a regular bookstore. That seems like the kind of thing that the mainstream companies are dying to do: to get stuff into bookstores. They make a big deal when something breaks outside of the insular world of comics. And this, by its very nature, is outside of comics. And that seems like the kind of thing that the comics press would want to investigate and talk about, even aside from the fact that it’s awesome, which it really is.

Thanks.

And that’s why I wanted to interview you.

Well, ever since I was a kid–you know, I’ve been doing comics for a long time. And very often they’ve had sexual content in them, which always felt perfectly natural and not particularly gratuitous to me. And it always seemed to me when I was making my comics–(sighs) I feel so stupid after that photo shoot.

They (the crew) were having a great time. I can tell you they enjoyed –

–watching me jump around like an idiot?

No, not watching you jump around like an idiot. They thought they were getting something good.

Yeah, they were fun. Okay, what do I want to say? I’ll ask you: What do you think my stuff is about? Fuck, I don’t know what to say, because I have no idea how other people look at my work, okay? And I think part of my confusion is because I’m not really a cartoonist, because I’ve been largely ignored by the cartooning world.

Were you involved when Raw was going on?

No.

And you’re not published by Fantagraphics. I feel like both of that explains a lot.

Yeah, I guess so.

I guess Drawn and Quarterly is a big deal, too.

No, they never published me, either. In fact they asked me to do a story once, and they said they’d have to see roughs.

Are you shitting me?

And I told them, “Sorry. I can’t do it.”

So how do I look at your stuff? I do look at it as autobiographical, but it’s better than most autobiographical comics for a variety of reasons. First of all, if it is autobiographical, you’ve had a very interesting life. It’s not just like, “Oh, I’m in high school or college, and I really like music, and this other girl kinda likes music, and we start listening to records together, and it looks like it’s going somewhere, and then things kinda get weird, and we go our separate ways, and I look back on it years later.” (apologies to whichever denizen of the Comics Journal message board I stole that summary of autobio comix from –ed.)

That’s kinda the story, though! (laughs)

Well, it’s sort of, but that seems to be the bread-and-butter twentysomething autobio, which is dull and done to death, and there’s more interesting things going on. So in terms of the kind of plot you can get out of an autobiographical comic, it’s interesting. Secondly, you also can draw really, really well in a variety of styles.

Thanks.

It’s my pleasure. And that makes it really, really compelling. The overall voice that emerges is so different than what I call “Sensitive 19-Year-Old Comics”: the usual guy-written autobiographical comic, characterized by a scene where the protagonist is hanging out with some girl, and she’s sitting somewhere looking uncomfortable in panties. She won’t be naked, but she’ll be topless.

This is what you do?

No, this is not what I do. This is what I think a lot of autobio comics do. I call it Sensitive 19-Year-Old Comics because it happened when they were 19, and they’re too sensitive to show the girl naked, because that would make them some troglodyte. They’re not a troglodyte–of course not! They’re really sensitive to her needs and feelings–but they still wanna see their titties. Hence the topless girl sitting around in panties.

And me, on the other hand: I like to draw pictures of guys from behind with their balls hanging out, because I think it’s kinda funny. (laughs) No. I want to make a movie. And I keep talking about it, but I really really wanna do it. And I see so many things that piss me off. Things like Lolita really piss me off. And this movie I want to make, it’s gonna be so much from a girl’s point of view, like I wanted the book to be. It’s hard, because we’re trained to see things from a man’s point of view. Even women expect the woman to take her shirt off in the movie. Those images become sexualized to women, too. Because that’s what means sex in this society: the naked woman picture. I mean, maybe that’s changing. I really like this (taps on issue of A&F Quarterly) because you’ve got lots of men, which is just as erotic as the girls and naked women, let’s face it–and women respond to it. They’re just not accustomed to it, that’s all. You’re so used to being bombarded with these female images.

And I think guys respond to it too. We have a big gay audience, but we also have football players and frat boys and lacrosse players. They love the clothes and the whole aesthetic, and they don’t even pick up on, perhaps, what they’re responding to.

Look, isn’t there something sensual about that? I say there is. And it’s also a matter of we’re all human and we have a certain amount of self-love, right? And it’s this narcissism that’s natural and keeps us alive. And so looking at pictures of people of our own sex, it’s sexual. But I think that the laws about pornography–I mean, you can show a woman with her legs spread and some spray on her to make her look like she’s all hot and bothered, right? And then you can’t show an erect penis. I mean, tell me why? I’ve said this before, but, a man can pick up a Playboy and see a beaver shot and jerk off on it thinking, “Oh, she wants to get fucked”. But Playgirl magazine has flaccid penises. I mean, who’s gonna pick that up and think, “He wants to fuck me”? You’re not. I think those laws were made because men are homophobic and also afraid of women’s sexuality. It’s men who make those laws. It’s really totally arbitrary and doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. And so the sexuality has been kinda trained out of women and homosexual men in our society. It’s not expressed. Maybe it’s beginning to be expressed. Anyway, this pisses me off. That’s why (slamming hand on book) I’m fighting against it, and (sighs) I hope I’m not the only one. But I’m glad to see this, I’m glad to see this (patting the Quarterly).

So, you’re trying to make a movie out of Diary of a Teenage Girl?

Yeah. I’m not really adapting it so much. It’s gonna be a movie with a similar tale.

I feel like people might hear that and they’ll think like a Larry Clark or Harmony Korine thing.

Who are they?

They did Kids.

Oh, no no no. I want to make it more like a Steven Spielberg film.

Really?

Big! Beautiful! (laughs)

That’s great.

This is my dream, ok? Also, did you see Irreversible? Gaspar Noé?

No, but I know who you’re talking about.

Yeah, that was kinda cool too. If you can imagine Gaspar Noé mixed with Steven Spielberg. A few little button-pushing emotional things that make you cry, but big, beautiful scenes of San Francisco and shots in a helicopter. And, you know, just… big.

That’s the opposite of what people would expect.

I know. I tell my husband that, and he’s disgusted, too. He’d prefer something like Kids, but I’m like, “Nooo!”

I’ve got you under my skin

In addition to comics and now film, you also do medical illustration. The first things I ever saw of yours were the illustrations that you did for J.G. Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition, and I was thinking what a weird melding of right- and left-brain thinking–to do those very particular illustrations, but then make art happen. How do you go about doing that?

I don’t know. In my comics or my novel or whatever, I’m really trying to understand something which to me is new and incomprehensible and really deep about a personality or people’s motivations. It’s more of a psychological thing. But in the medical art I’m looking for the same thing. It’s this–have you read that book Nausea? You know, Jean-Paul Sartre?

No, I haven’t read Nausea either. You’re making me feel very culturally illiterate.

Just with that one mention? Okay. No. It’s this feeling when you finally, suddenly in a moment, unexpectedly realize your humanity. You realize the physicality of your being. We walk around all the time forgetting that we’ve got this body. And when you suddenly at any particular moment are able to really feel that–that you really are a body–it’s almost sickening to realize that. And when you go deeper, like when you’re having sex, you want to know, what does that look like inside? What’s going on? I wanted to study medical art so I could go look at surgery, so I could see autopsies, so I could touch the inside of people’s bodies. But I didn’t wanna be a doctor. Unless you take anatomy for artists, you never really get the privilege of seeing living people operated on, or seeing people who are freshly dead. Something about it brings you so close to what it is to be human: always so precariously nearly dead, and so lucky to be alive. I mean, it’s such an accident that any of us are born. Anyway, that’s what motivates me either way. To me they seem almost the same: wanting to know and understand the psychological motivation and then wanting to understand, more deeply, what’s inside.

So you’re saying you just wanted to see, you just wanted to feel. It’s almost satisfying a curiosity. It’s not making any big claims about what it is to be human: whether it’s good or bad.

No, it’s not good or bad. I mean, nothing is good or bad. We only see it that way. Thinking makes it so. Honi soit qui mal y pense.Our system of morality is something we’ve built to keep us safe, because human beings have learned that certain things work for us and certain things don’t, but that doesn’t make them good or bad. That thing where they say you can tell if someone’s crazy by whether or not they know right from wrong–to me that sounds absolutely ridiculous, because what is right and what is wrong?

Like Charles Manson or Jeffrey Dahmer. Yes, they knew that killing was wrong, so they were legally sane. But Jeffrey Dahmer made an altar out of body parts and was praying it to get powers like the Emperor had in Return of the Jedi.That’s not sane.

That’s not sane. But is it any less sane than me sitting there thinking about what blowjobs look like in cross-section? Why am I thinking about that? You could say I’m crazy, you could say he… I mean, I don’t know.

Well, maybe it has something to do with the outlet. You drew it, and he would actually chop someone’s head off.

Yeah–and I would do it too if I thought I could get away with it. And if I thought it wouldn’t hurt them. But see, that’s what I know. I know it would hurt them and I wouldn’t want to hurt them. So is that knowing right from wrong? Maybe. It’s compassion. I can feel compassion.

Right.

Teenage rampage; Life, the universe, and everything

That actually brings me to another question. When you do work that can be seen as autobiographical, you’re also writing about, not just yourself, but the other people that you come in contact with. How does that affect people that you know, who may see themselves in a given character?

Since those people don’t exist, I don’t know.

Very nice.

Again, it’s my perspective. And I’m sure it’s very far from how they would see themselves. No one is there to say anything to me. I don’t think they even see the work, but I don’t know.

When you write about a teenager, I feel like there’s a natural tendency to condescension, because you’re older and you’re writing it, ostensibly, for older people. There’s a tendency to be like, “Oh, look at this silly girl. Aren’t you glad that you and I know better now?” But I think you avoided that. How did you do that?

I never thought teenagers were silly. Never did. Even when I was a teenager. I mean, I know from experience and you probably do as well. Actually, when you’re a teenager, you feel things very, very strongly. Everything is new and everything is very, very important. Why would that be silly? Because later on you become so inured to it, that you’re just kinda dulled? That’s the sad thing. That’s thing to laugh about.

One thing that’s always bothered me is when people pick on a particular type of story like that’s an “adolescent thing.” And comics in particular. I’m a superhero guy, and I don’t care that that’s not a cool thing to be or whatever, because I also read alternative stuff, and it’s all the same to me as long as it’s good. And it bothers the hell out of me the way people reflexively say, “It’s an adolescent male power fantasy. It’s teenage boys looking for something jerk off to.” What is so bad about being a teenage boy? Why is that the ultimate put-down? If you really wanna diss something and make the creator feel awful and shit on a book, you say it’s for adolescent boys. It bothers me, because they can’t help that they’re adolescent boys. And I remember when I was an adolescent boy and I read The Dark Knight Returns for the first time, or Watchmen, the stuff meant so much to me. And I know people who are gay who have X-Men tattoos, who love that shit, so it’s not really an adolescent-male-power-fantasy-over-women thing. For the girls, it’s “teeny boppers are the worst things in the world and they’re ruining music.” Whether it’s teenage boys with metal or teenage girls with pop, people act like it’s the teenage audience that’s ruining music. I’m just like, “fuck you.”

Right. What does it matter? The funny thing is, my husband really likes music so he feels he has a really sophisticated taste in music. Whereas I like pop music, and I like metal, and I tend to make lots of stupid butt jokes and fart jokes. He always says that I have the mentality of a 12-year-old boy. I make dirty jokes that I think are hilarious and he’s too sophisticated to think they’re funny. But he always says that to me, and it’s like the ultimate put-down he can always tell me. And I like to fight too. I don’t know why. I was born like that. My dad fought. And my husband always says, again, that I’m acting like a 12-year-old boy. And it’s too bad. I’ve never even known many teenage boys –ever, really –because I was scared of them. But I don’t think there’s anything wrong with them. And you’re still something of a teenage boy at heart.

Sure.

Yeah, I mean, definitely.

Well, I like the same things that I liked when I was a teenager.

I do too. And maybe that’s one of the reasons why I wouldn’t think that I would condescend to a teenager. I think some of the things that I discovered when I was a teenager were so powerful to me. They still are. They still sustain me in many ways. I don’t think it’s silly. I wouldn’t say, “Oh, it’s so stupid, I liked it when I was a teenager.”

Well, speaking on my own behalf, I’m married to the girl I was going out with when I was 16. I have this job that is just, like, arrested-development city. I interview the comic people that I like, the authors that I like, the musicians that I like, many of whom I liked when I was in adolescence. I still spend all my money on books and cds and comics and dvds, the same stuff I was buying when I was a teenager. And my wife’s a teacher, and she comes home everyday with stories, everyday (voice cracks)–Oh, gee, my voice is cracking like a teenager. And she comes home with stories about how insightful or inspiring her teenage students are. And what is appealing to me and my wife about your book was that it didn’t feel condescending at all.

And I hope it didn’t feel condescending to anybody. Because the matter of fact is, I love all the characters. This sounds so stupid, but a lot of my motivation for doing things is that I’m just a confused person. I love and hate things so strongly and often at the same time. And when I’m making a book or something–drawing the people, writing the book- it’s almost like I’m playing with dolls. I can feel them and hold them and move them around. It’s such pleasure to me. And you’re right, I don’t judge them, simply because I don’t think that I understand right from wrong. (laughs) Mark me as crazy! Actually, I do watch Court TV all the time when I’m drawing. And it scares me. It’s so fascinating to see the defense lawyers. And I saw this fascinating trial of David Westerfield, the guy who killed his neighbor, murdered the little girl. And he seemed like such a straight engineer, living in this wealthy more or less upper-middle-class neighborhood. And his defense lawyer knew all along that he probably did it, because they were doing some plea bargain with him before the trial. He was about to admit he knew where the body was and they would give him some lesser sentence, but then they found the body on their own and they took it all away. But his defense lawyer obviously knew that this man was guilty of killing a child and doing God knows what else. And yet the defense lawyer’s job was to defend this man. And at that point this question of right or wrong totally deteriorates. It’s our system of justice, based on the fact that everyone needs a defense and deserves a defense. Evil things, things like murder, are done, and somebody did them. And you may very well know that you’re defending someone who is guilty, but yet your belief in the system that says everyone needs a defense is stronger than your belief that this person needs to be punished. It’s got to be. And so it’s an idealistic thing. You’re fighting not so much for this person but you’re fighting for a belief in the system. And to me that’s like totally schizophrenic. But at the same time it’s fascinating. And it’s also fascinating to try to understand why someone would do something like that. And I don’t understand it at all. And why am I getting on this track? It’s just this idea of being judgmental. Sometimes I think I am, because so many things just–it doesn’t boil down to logic. It boils down to this bubbling seething mass of possibility and things go one way or another and… I don’t know. Things don’t make perfect sense. And religion and art are two things that are abstract that we try to explain life with, and we don’t know if we have any answers. There was something I really wanted to say, but I can’t get at it… What I’m getting down to is that you can understand anybody’s motivation if you want to. I could go talk to David Westerfield. I could take his face in my hands. Look him in the eye. Feel his scalp. Feel his pulse on his neck. I could do this and talk to him until I felt like I understand why he did what he did. And at some point I could understand it. It doesn’t mean I would do it. But I could understand it and feel how he felt he could do that and was allowed to do that at that moment. And I mean, when you’re able to say you can understand anybody, or it’s possible to whether you’re capable of it or not, then how can you judge anybody? It’s kinda scary actually. Because if everyone was like that and they were thinking in this way, then we’d just have anarchy.

To me, political good, moral good, the goal of all of that, is to maximize the amount of choice that everyone has to do what they want and be what they want. And the way you determine if something is bad is if it’s adversely affecting someone else’s ability to be free and to choose freely. I don’t know if it’s from being a Tolkien fan or a Star Wars fan, or if it’s just a kinder, gentler, bastardized version of Aleister Crowley, but I do believe in right and wrong very strongly. And to me what it is right is making sure people are free to do the good that’s in their heart to do.

That’s also very Quaker. I grew up Quaker, going to Quaker schools. And it was always like, “You don’t need an intermediary between you and God. God’s inside of everybody. And you only need look inside yourself and find this inner light and that will inform you and you will know who God is, what God is.”

When I developed this code, I was in a sense bypassing God and going to the spirit of man and the spirit of humanity. Kinda like the Force (laughs). Actually, I do believe in the mystical/supernatural/spiritual kind of side of things. In the end, I think that inside each of us is something to be true to–something that people were put on this earth to be true to.

I believe that too. But it does have something to do with letting other people believe it exists at the same time, and they may even be wrong. Which is easy in retrospect. It’s not easy in real life every day. Because things bug you that people do, even your wife or husband or whatever.

Pascal

I wanted to ask you about Pascal, Minnie’s former quasi-stepdad in Diary of a Teenage Girl. Probably one of my favorite parts of the book, in a weird way, is how you really believe just from his letters to Minnie that he’s not perfect, he’s a little weird, he doesn’t really know how to relate to people, but he has Minnie’s best interest at heart. He really is looking out for her, he cares about her in some way, he’s trying to keep her away from this other guy –and then you find out he was fucking this other teenage girl. In other words, it took one to know one essentially, and that’s where he was coming from with his “concern.”

But he probably did still really care about her.

Then why did he do what he did?

To the other girl?

Yeah.

It wasn’t her.

I guess it was just a heart-breaking part of the novel, because I read A Child’s Life one day and then DOATG over the next three days, and my wife was two days behind me each time. She got to a certain point in the book and she was like, “This Pascal guy who’s writing her, is he the same guy who’s really mean to her in A Child’s Life?” And I was like, “Yeah, no, he seems like a pretty good guy, ultimately.”

But it’s always this twisted thing.

Exactly–then I got to the point where you find out what he was up to with this other girl, and I couldn’t believe it, because I fell hook line and sinker for it.

The character is that type. He’s a man who did want to love and care for other people, but he was also really selfish and insecure, but he was very intelligent. Like in A Child’s Life, he really did want to make this a family. He was a Scotsman. He wanted to make this nuclear family out of these broken parts and adopt Minnie and her sister. He wanted to. But something in him was so threatened by it that he had to break everything. And he did that repeatedly in A Child’s Life, when he finally said, “After you questioned me all those times, I can’t possibly even consider adopting you.” And he did the same thing when he was sleeping with her friend. In a sense, it’s weird, because sleeping with her friend is almost a surrogate for sleeping with her. He seemed to have this very caring relationship with her, writing her these letters and everything else. But it wasn’t the physical thing. But at the same time it was like a betrayal because he wasn’t sleeping with her. So did that mean he loved this other girl more? I mean, it’s like a sick thing for Minnie, who was so accustomed to being sexualized inappropriately. She might even feel betrayed because it was this other girl and not her. But at the same time she feels sick because she knows it would be wrong. So essentially she had to cut herself off not only from his sickness but from his care for her. Because I do think he did care for her. And in a way that was actually helpful. He was telling her she was smart, and no one else was. So she was getting that from him. But that had to end after this thing with her friend. I mean, everything had to end. And that is very sad, because she had to lose everything. I don’t know if it’s painted this way, but I think Pascal was a kinda fucked up person. But it wasn’t to his advantage. He was hurting himself too. You don’t ever see him in that book; it’s just the letters. Does that make sense? Because it is the feeling that he was hope for her. Yeah.

Music; The big finish

Anything else?

This question is sort of just for me, but I really liked Minnie’s taste in music, because it was so ecumenical. She’d be like, “I went to the store and I got Bowie, Pink Floyd and Donna Summer,” and I was like, “Oh my God, that’s so awesome,” because that’s my iPod. What kind of music do you listen to now?

I like anything. I seem to like anything with a beat and a rise and a swell that kinda takes my heart along with it. I don’t know how to describe that. It doesn’t have to be rock and roll, it doesn’t have to be anything. It’s just gotta be something that… I like voices with a lot of feeling in them. How do you describe it? I don’t know. You might argue that Bowie’s kinda cold or something, but he’snot.

What I liked about it in the book was that I used to hate disco. I used to hate a lot of things, actually, but I just don’t have the energy to hate any type of music at this point. I may hate a particular artist because I just think they’re full of shit. But anyway, someone had a Barry White collection my sophomore year in college. And I appreciated it for kitsch value. But when I read the liner notes, which were written during the grunge era when disco was really being shit on, Barry was like, “Disco was about people going out and feeling beautiful –”

People feeling themselves–

And the music was beautiful, and having a good time, and feeling good about yourself. And I had never heard it put that way, because I always just thought of John Travolta in a white suit. And I was like, “Jesus!” You know?

And you can feel that. And some of my best experiences growing up as a teenager in the 70s, walking down the street at night and just passing bar after bar that I couldn’t go into because I was a teenager and seeing disco lights in the street and hearing disco music. I just loved it. Nothing better than walking at night and listening to that in all these places. But you made me think of something. I’ve always loved disco music. And in the late 70s I became a punk rocker and cut off all my hair and safety pins and all that crap and went to London –you know, all that shit. But I was one of the only punks who loved disco. I loved it. But I have to admit. I always hated hippies.

Well, I think there’s something a little bit self-righteous about a lot of hippies. I can’t even imagine being in San Fransisco in the 70s.

Yeah, they disgusted me. I can remember feeling repulsed by the hippies. Deadheads.

I really do have a hard time now getting worked up about genres of music, though. It just seems silly.

But some of my favorite musicians –like Janis Joplin, I just love. But to me she was never a hippie. She was sweet and generous. She was something different.

Even as into glam as I am–which sometimes you’ll see described as a reaction to Creedence Clearwater–I love CCR.

But nothing is a reaction, because what self-respecting musician or artist would just do something in reaction to someone else?

Even Bowie –in “All the Young Dudes” he was dissing the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and then he’s like recording with John Lennon and hanging out with Mick Jagger within two years of that. Anyway, after that I got into funk music–

Parliament–

James Brown, Sly and the Family Stone, Head Hunters. Then I would listen to K.C. and the Sunshine Band or the stuff that Donna Summer did, and I was like, “I understand this now!” The beat, the syncopation–

It was beautiful. Like, “I Feel Love”–it takes up your whole heart!

And you can hear where bands like Underworld where are coming from, this huge emotional–

Yeah. And the beat is the heartbeat. Do you know Lucinda Williams at all?

Yeah, but I haven’t really heard much by her.

I really liked her at one point. I don’t know if you’re this type, but I get stuck on one record and I keep listening to it again and again. Just pushing the same buttons in my brain or something. And then I get sick of and come back to it later. Anyway, I was listening to that, and then I got Led Zeppelin. And see, I hated Led Zeppelin when I was a teenager. But I listened to Led Zeppelin and it’s really good! That record, you know, “Stairway to Heaven,” that’s a great record! But it was so funny because she takes some of these same riffs, directly plops them into her music, but if you listen to her music as a whole you’re not gonna say she sounds like Led Zeppelin. But it’s like an homage to Led Zeppelin. She’s just taking it and using it in a different way. But it’s just so fascinating. I’m not a musician, so I just, I love music. Yeah, see, I will listen to Led Zeppelin really loud in the car.

Yeah, fuckin’ A!

Yeah, fuckin’ A! See, that’s why my husband says I’m like a 12-year-old boy. But–

Led Zeppelin specifically, I don’t know if I could imagine what my life would be like without them. That 10 CD box set of theirs was like the Rosetta Stone for me when I was younger. And I think we’re fortunate to live in a time where you can download individual songs, and have on your iPod 500 songs or whatever. Today on the walk over here, I was listening to “Automatic” by the Pointer Sisters and “Rocky Mountain Way” by Joe Walsh. You can’t think of two songs written by two more different people for more different purposes, and neither is critically acclaimed, but those songs will be working in some unidentifiable way in my head.

Being able to not limit yourself. There are so many great things you can draw from this. When you said your boss didn’t want interview cartoonists because you’ve done too many already –see, I don’t think of myself as a cartoonist. And I don’t know if it’s because I don’t feel accepted by people who read cartoons, or because I do so many different things. I think I would be bored if I said, “I’m gonna do this this way, make a series in this same format.” Maybe that’s why my stuff’s not popular–because it’s not coming out predictably. Who knows? Look, my stuff is about me as much as it is about you. You wouldn’t be able to relate to my stuff at all if it wasn’t about you, too. I want it to be more universal than that. I’m a medium through which–I use myself as raw material. But I’m like anyone else. I don’t care if it’s about me. I really believe it’s about you. Or anybody. People ask me if I’m embarrassed: “Isn’t this personal?” Of course I’m not embarrassed! What makes me different than anyone else? It would be hubris to censor myself. Do you know what I’m saying? I’m not trying to protect myself in any way. That would be dishonest. What do I have to protect?

I think that’s pretty brave.

But once you start protecting things it’s no longer true. You would no longer understand what I’m writing. You would think, “This is a weird voice, this sounds condescending,” or “I’m not getting anything from it.” You wanna touch people. Whether it does or not you don’t know, but you wanna be touched. Fuck, you know what I’m talking about–I don’t know. The weirdest thing about making a book is that you can’t just tell a story from your life. No one is ever gonna want to read it. You have to give it a narrative thread. It’s all artifice. You have to do that. Make it entertaining. And if you don’t make something entertaining, it’s not gonna get to anybody, because there’s a certain way people communicate. Even the things that are least accessible, like J.G. Ballard–it’s not accessible at all, it’s far from entertaining, you have to teach yourself to be entertained by that. But I don’t wanna be that obscure. You have to try hard to be entertaining. Shit, you write….