[Chorus: Pat McGurn and Morgan]

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

He’s firing somebody real, fired by fuckin’ Dalton

Send your goons to the bar, maybe he’ll assault them

[Verse 1: Tilghman]

Hold up, Jasper simmer down

Hiring the best, bitch, now he’s here in town

Flew to New York, saw him shirtless, lookin’ fine

Ooh, baby check him out, you’ll go Jeffrey Healey blind

(Uhh)

Hey Pat, black coffee

Serve this motherfucker cuz he drinks for free

Tell these motherfuckers who they think they see

Put his feet through your teeth then he’ll break your knee

Cuz he’s the cooler, the cooler cooler, like he’s your ruler

Teaching rules too, he’s gonna school you, don’t suffer fools too

He should carpool, like many fools do he searched for faith down at NYU

Hospitalize you, that’s what he will do

Here’s my money, gonna give you six figures, man

I thought you would be bigger, man

Wesley’s fuckin’ parties make too much fuckin’ noise

Break into Brad’s house, kill his fuckin’ boys

Beast

[Chorus: Pat McGurn and Morgan]

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

He’s firing somebody real, fired by fuckin’ Dalton

Send your goons to the bar, maybe he’ll assault them

[Verse 2: Morgan]

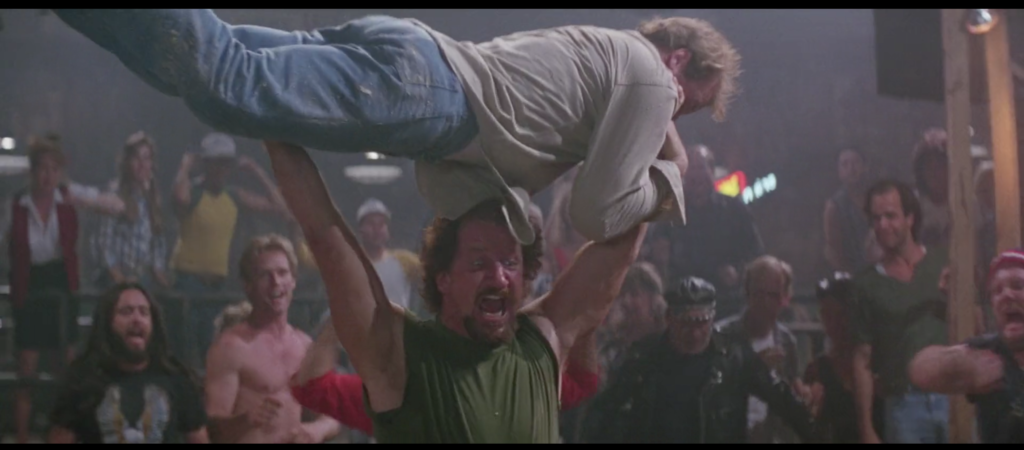

Ooh, I know you love it when I bounce a guy

Make you think about all of the incidents I trounced a guy

Go into the bathroom and ask Judy for an ounce to buy

Think I’ll tell him “You’re a dead man,” mispronounce a guy

Oh word? Ain’t heard of Wesley? He’ll denounce this guy

Beating up O’Connor, make him bleed some fluid ounces guy

Carrie Ann announced this guy, see his mullet flounces guy

Then ju—okay, I got it

Then just watch Jimmy as he pounds this guy

It will get awkward when we watch as Jimmy mounts this guy

I heard that his testes were sufficient for a dump truck

Then he said “Opinions vary” and I felt like such a dumbfuck

Gonna call Wade Garrett “Dad,” comparatively I’m a young buck

Then I’m gonna die offscreen while wearing moonboots, just my dumb luck

Yes, Lord, but for now I’m fit and able

Gonna pick some guy up, throw him through a table

I’m beast

[Chorus: Pat McGurn and Morgan]

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

He’s firing somebody real, fired by fuckin’ Dalton

Send your goons to the bar, maybe he’ll assault them

[Verse 3: Pat McGurn]

Uhh

I’m Pat, this the finale

A big truck at the Wagon Days rally

I’m behind the bar, taking money from the tally now

Told me take the train and told me not to dilly-dally

Mmm

Uncle Brad on the line, mad on the line

He’s opening two Dillard’s at the same damn time

Frank’s eyeing me like he still wants to have sex

Girl, I am John Doe from X

Girl, I’m Patrick McGurn

AKA Brad looks at me with concern

He gives me money that I do not earn

Lists me as a dependent on his tax return

Mmm

Kill ’em all, dead bodies in the hallway

Dalton’s involved, and my chest got in his knife’s way

Mustache thin, Morgan thicker

Sister-son, chickendicker

Beast

[Chorus: Pat McGurn and Morgan]

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

He’s firing somebody real, fired by fuckin’ Dalton

Send your goons to the bar, maybe he’ll assault them