The same year he starred as Morgan, the man who tells Patrick Swayze he’d heard he has balls big enough to fit in a dump truck, in Road House, Terry Funk was a peripheral participant in what is widely considered to be the greatest series of wrestling matches of all time.

In 1989, “Nature Boy” Ric Flair and Ricky “The Dragon” Steamboat battled back and forth for the NWA World Heavyweight Championship in three major televised events: Chi-Town Rumble, Chicago, February 20; Clash of the Champions VI, New Orleans, April 2; and the inaugural Wrestlewar, Nashville, May 7. Each match ran over half an hour of continuous wrestling, significantly more so in the case of the Clash of the Champions fight, which was a best-2-out-of-3 falls encounter. Flair was a flamboyant bleached-blonde self-styled playboy and the greatest heel in wrestling; the contrast with Steamboat, with his raven hair, his presentation as a serious martial artist and working-class family man, and the purity of his babyface goodness, sold itself.

But the wrestling formed the real narrative and set a new standard. Naitch and the Dragon chopped, stretched, tossed, and slammed the holy hell out of each other in epic back-and-forths in which each individual body part being worked on felt like a pivotal supporting character. The trilogy charted Steamboat’s upset capture of the title from longtime champion Flair in Chicago, his successful defense of the belt in a controversial finish at the Superdome, and his almost anticlimactic defeat by Flair to regain the championship in Tennessee. (They fought each other at off-air “house shows” dozens, perhaps hundreds, of times; some of these fights, by their own account as well as those of contemporary observers, were even better than the big three canonical bouts.)

These matches are available on WWE’s proprietary streaming service, and may also be located with minimal google-fu on YouTube or one of its knockoffs. You can sit and watch all three matches back to back and feel as if you’re watching an intimate epic, The Return of the King crammed into the deliberation room from 12 Angry Men. If you want to be entertained and awed by the world’s most lucrative outsider artform, I can’t recommend “the trilogy” highly enough.

I bring this up not only because I just watched the trilogy for the first time, but because Terry Funk’s presence was such a treat for a Road House mark like myself. While absent for the Chi-Town Rumble fight, he was one of two ringside commentators during CotC, as well as a judge and…let’s say “audience participant” at Wrestlewar. I’ll tell you this, fight fans: Anyone who thinks Terry Funk isn’t one hell of an actor needs to listen to and watch those last two matches.

In the first, Funk is largely an offscreen presence, and an ebullient, gracious, and sweet-natured one at that. His distinctive, soft tenor rasp provides a sense of almost childlike delight at the herculean feats of Steamboat and Flair in the ring; if “I’m just happy to be here” had a voice, it would be Terry Funk’s during this match. Where is the man who called Dalton an asshole and a dead man?

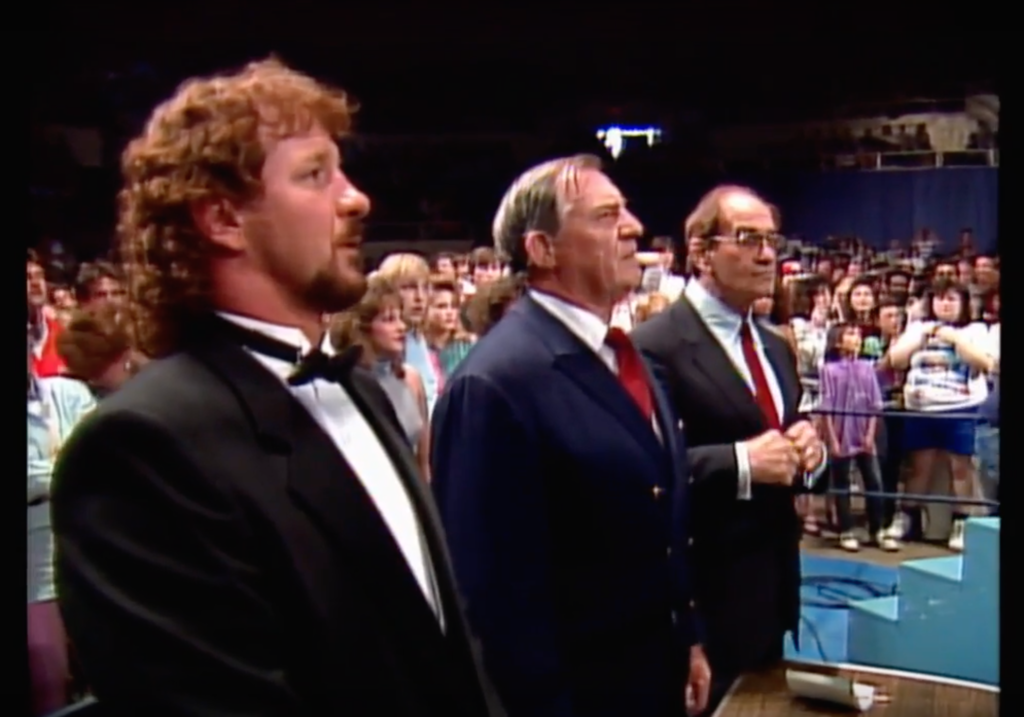

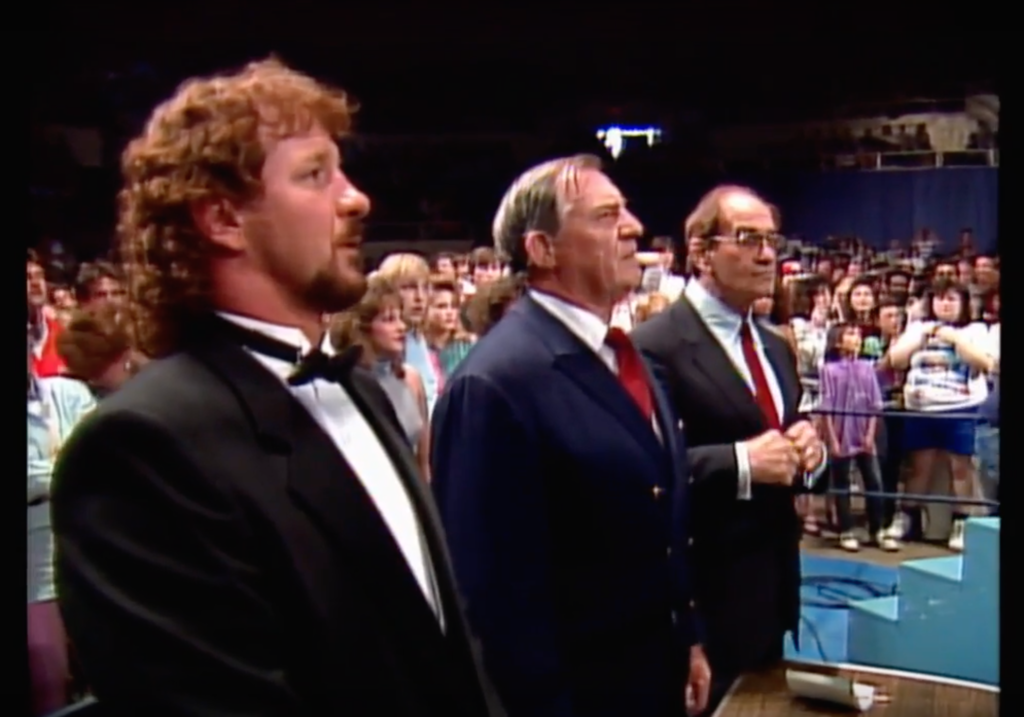

He’s biding his time until the following month, that’s where he is. That is when, while Steamboat is still exiting the arena and his prior commentary colleague Jim Ross attempts to interview the triumphant Flair in the ring, Funk awkwardly inserts himself, repeatedly congratulating the new champ. It gets weirder and rings phonier as the segment goes on, and Flair, whose display of stamina and guts during the whole titanic series of matches had largely won over the crowd at a time when the line of demarcation between heel and face was much firmer than it is today, gets pricklier. When Funk says he’d like to be the first to challenge Flair for the title, it feels inevitable, and Flair’s pushback—that there’s an entire ranking system of top contenders, all of whom were around while Funk was off hobnobbing with Sylvester Stallone in Hollywood—feels justified.

Funk, as you might have guessed, disagrees, and goes absolutely apeshit.

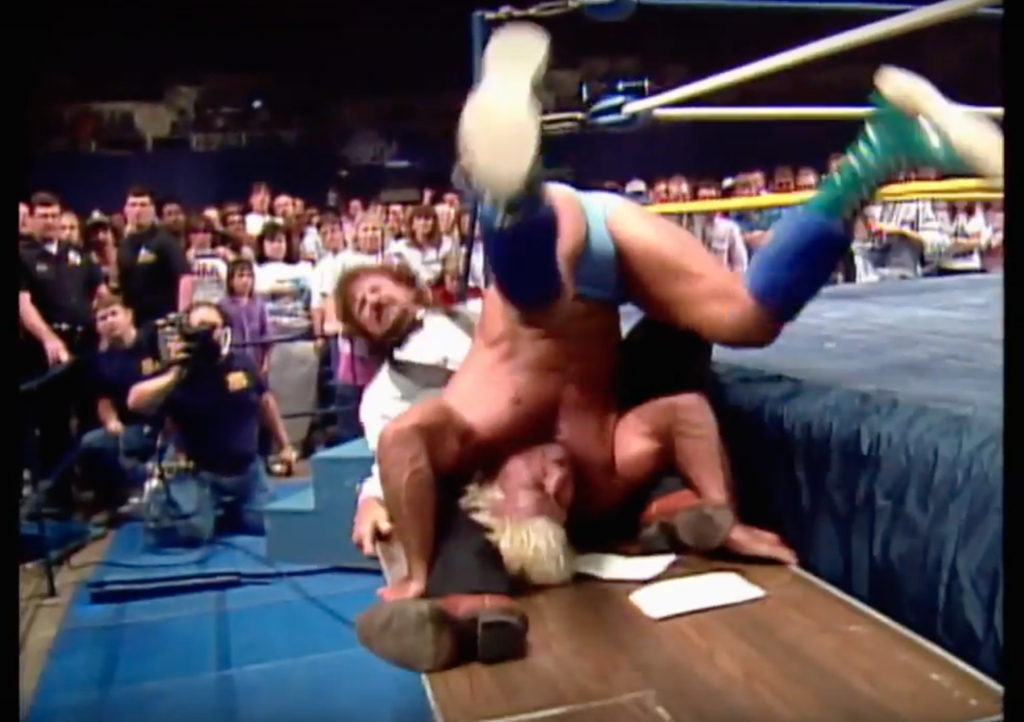

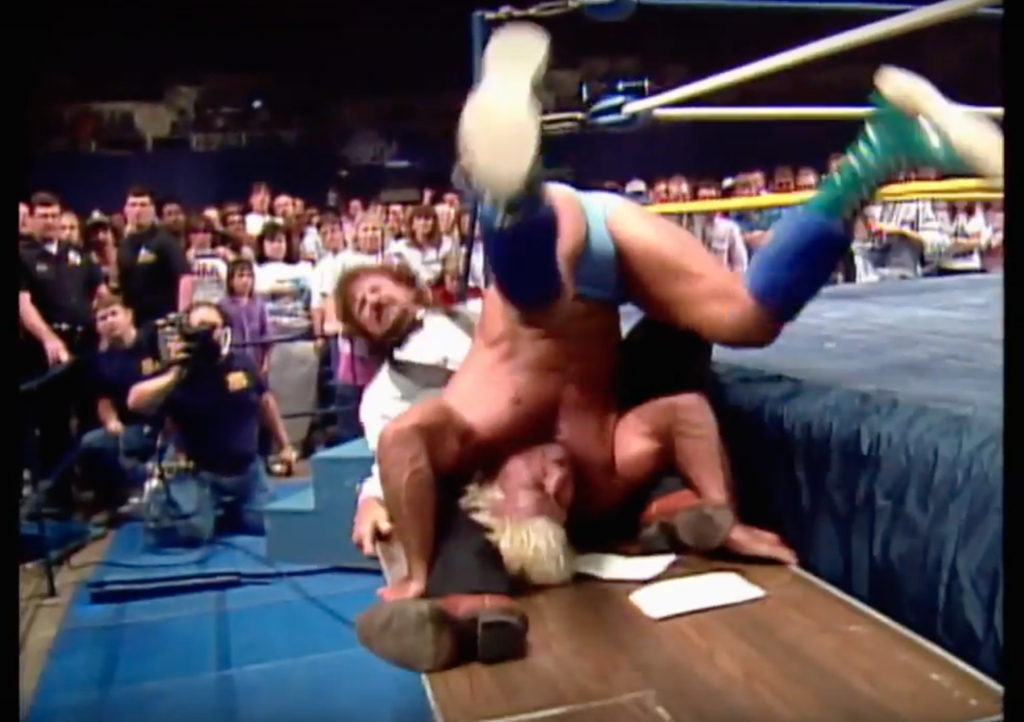

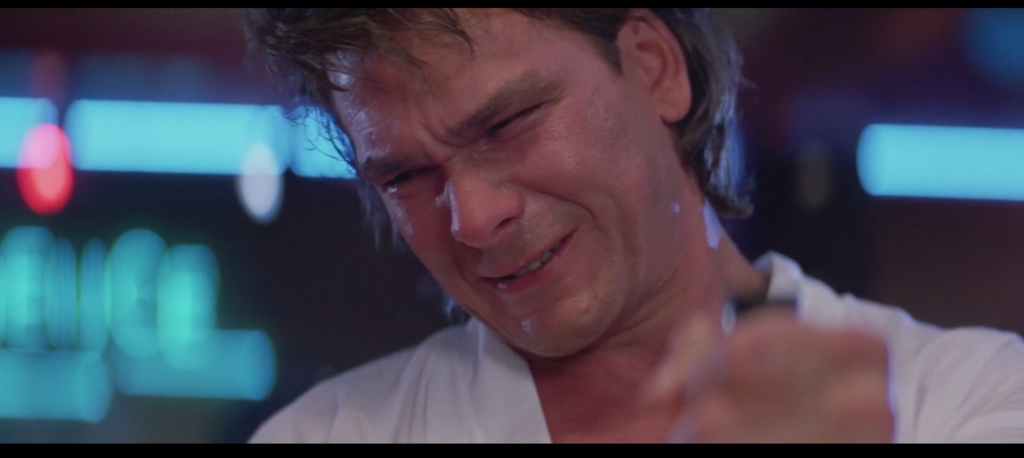

He suckerpunches Flair, blasts him right out of the ring, and goes to town on him with the security railing, with a table, with a chair. In one spot that’s particularly frightening now, after a few intervening decades of broken necks and CTE, he piledrives Flair’s skull directly into the tabletop, toppling the whole edifice to the ground as they collapse onto it afterwards. Throughout, Funk is so furious he actually appears to start crying, tearing off his tuxedo jacket and screaming “You think you’re better than me???” at the defenseless champion while shrieking at the aghast and angry crowd.

Less than two weeks later, on May 19, Road House debuted. Along with the Clash and Wrestlewar matches, it comprises a Terry Funk trilogy of its own.

I feel I understand Morgan the bouncer a bit better now after watching Steamboat/Flair II and Steamboat/Flair III. After his genial turn as an announcer I can see how he might have sweet-talked Frank Tilghman into hiring him, and perhaps even initially persuaded his coworkers to like him. After his psychotic rampage, I can see why no one dared to fire him despite his manifest unfitness for the job, and why Brad Wesley kept him on the payroll to protect his nephew and his investments. After both, I see why Rowdy Herrington cast the person he cast for the role. You could say that Terry Funk brought a lot to the table.