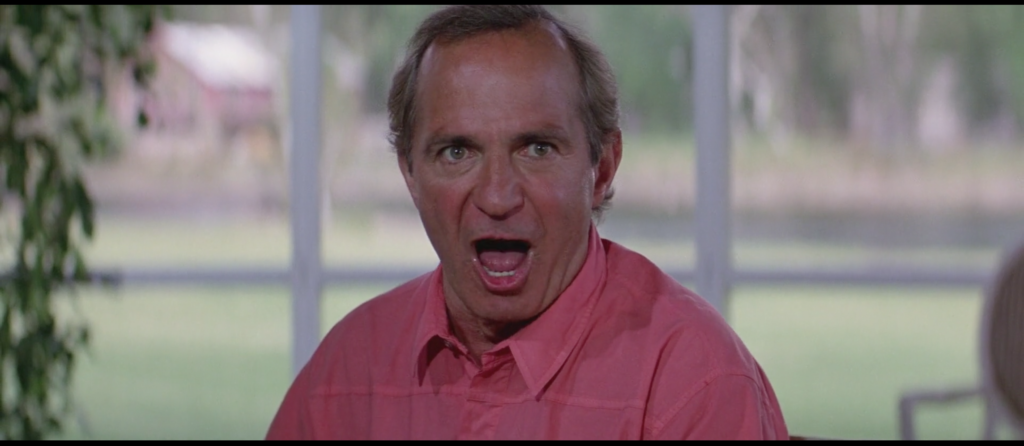

At least I assume it’s Grandpa Wesley; it’s hard to imagine Brad Wesley celebrating his matrilineal anything, even his kindly Pep-Pep. What’s for certain is that the black and white portrait on a table in his breakfast room (at least I assume it’s his breakfast room; a man of Wesley’s pretensions to feudalism almost certainly has a long oak table with high-backed chairs somewhere around that hideous house) is a portrait of his grandfather, as he announces without looking up from his breakfast when Dalton pauses in front of it.

“Looks like an important man,” Dalton says.

“He was an asshole,” Wesley replies.

This is one of my favorite stupid exchanges in the movie for a variety of reasons. Judging from the not just conciliatory but outright deferential tone Dalton adopts when he proclaims Grandfather’s importance—the “looks like” is just a turn of phrase, you can hear in his voice he’s quite certain it must be so—it’s quite possible that this was the last opportunity for peace in our time between the two most lethal men in Jasper, Missouri.

Despite enduring multiple physical assaults and murder attempts, despite seeing what Brad Wesley does to the woman in his life, this is Dalton attempting to meet Wesley where he lives, no longer just literally but emotionally as well. Surely, surely he can get this crazy old bastard to wax nostalgic about the lessons Papaw taught him, tough but fair no doubt, thunder in his voice but warmth in his heart, taught me the value of a dollar, when you forgive your enemies you create friends, you and me Dalton we’re not so very different are we?, you can hear it all play out in your mind just as clearly as Dalton could. Who would expect Wesley to grab hold of the proffered conversational life preserver long enough only to stick his ass into the middle and use it as a makeshift floating toilet before sending it bobbing on back? Not even the second greatest cooler in North America, I’ll wager.

Which is why I believe this to be one of the few occasions in which Dalton’s cooler-sense fails him.

Consider: His powers of observation, of sight and sound, of the sixth sense that can tell when trouble has walked through your door in knife-augmented boots, are unmatched at this point in the film.

Then consider: Here is the room he walked through in order to reach Brad Wesley.

What about this picture suggests to you that Brad Wesley uses the dead for decoration because he misses the time when they were alive?