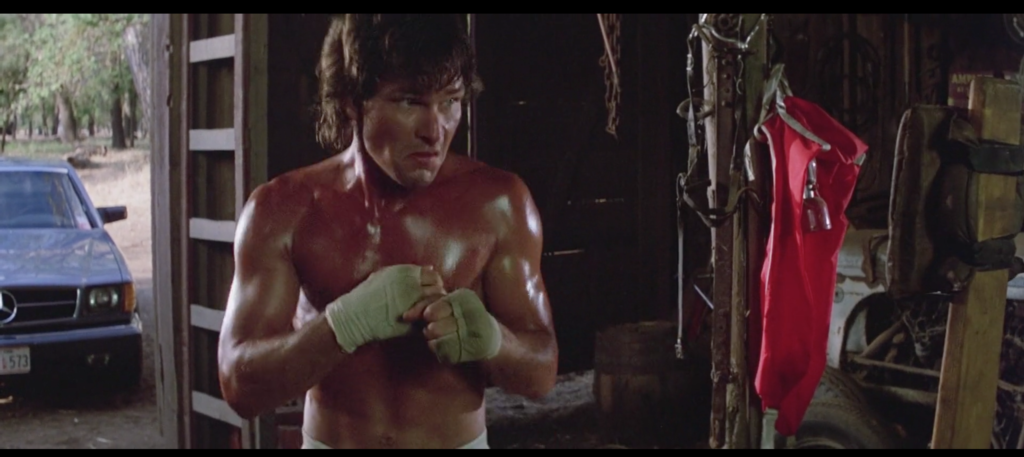

One of the reasons it’s easy to tell that Dalton isn’t holding a cigarette at the start of his confrontation with Dr. Elizabeth Clay, despite the appearance of one in his hand by the end of it, is the positioning of his arms. They’re crossed above his stomach, and stay that way as he turns toward her, ranting and raving about how he’s seen the likes of Brad Wesley many, many times. I can’t say that I’ve seen the likes of Dalton many, many times, at least insofar as I’ve never argued with a shirtless man who walks around with his arms crossed like he’s in a straitjacket. It looks very, very weird, especially when combined with his petulant tone of voice and jut-jawed, neck-straining body language.

One of the reasons it’s easy to tell that Dalton isn’t holding a cigarette at the start of his confrontation with Dr. Elizabeth Clay, despite the appearance of one in his hand by the end of it, is the positioning of his arms. They’re crossed above his stomach, and stay that way as he turns toward her, ranting and raving about how he’s seen the likes of Brad Wesley many, many times. I can’t say that I’ve seen the likes of Dalton many, many times, at least insofar as I’ve never argued with a shirtless man who walks around with his arms crossed like he’s in a straitjacket. It looks very, very weird, especially when combined with his petulant tone of voice and jut-jawed, neck-straining body language.

But Dalton is in a straightjacket, isn’t he? One of his own making. He refuses to quit the town because of his feelings for the Doc and his anger towards Brad Wesley. But he also refuses to listen to the Doc, who’s telling him to forget his anger towards Brad Wesley and just get the hell out of there. He’s staying behind for the sake of someone who wants him to leave. His motives are crisscrossed, just like his arms.