Bottomless Bellybutton

Dash Shaw, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2008

720 pages

$29.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

I finally got around to reading this Blankets-sized graphic novel over the past weekend. (Doing most of your reading on the commuter railroad disincentivizes taking a crack at really big books. Sorry, Bone. What is it with gigantic graphic novels that begin with the letter “B,” anyway?) It has more in common with Blankets than simply the initial and the size. They’re both works of great ambition from young authors–statements as much as stories–that tackle love, family, and the conflict between the two. They’re also both very, very successful.

The story takes place over the course of an awkward weekend-or-so at the home of the Loony family. The parents of adult children Dennis, Claire, and Peter have summoned their kids and their respective families or lack thereof to inform them of their impending divorce, after forty years of marriage. The set-up itself contains a rich vein to mine; as someone whose parents split up when I was an adult, I’ve never seen that uniquely pleasant situation this convincingly depicted, as once-intimate and effortless family dinners become merely cordial, well-worn anecdotes take on the feel of elegies, and being forced to think of your parents as full-fledged sexual, emotional, and psychological beings whose dreams have in some major way not ben fulfilled takes its toll.

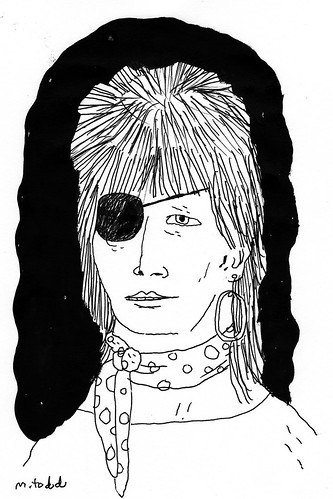

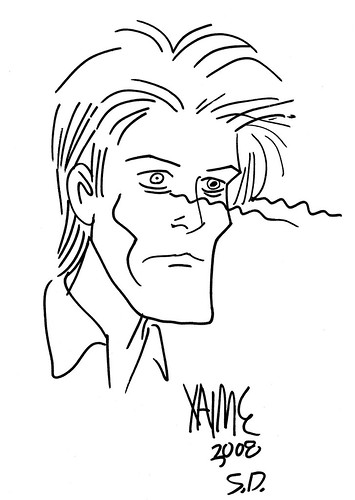

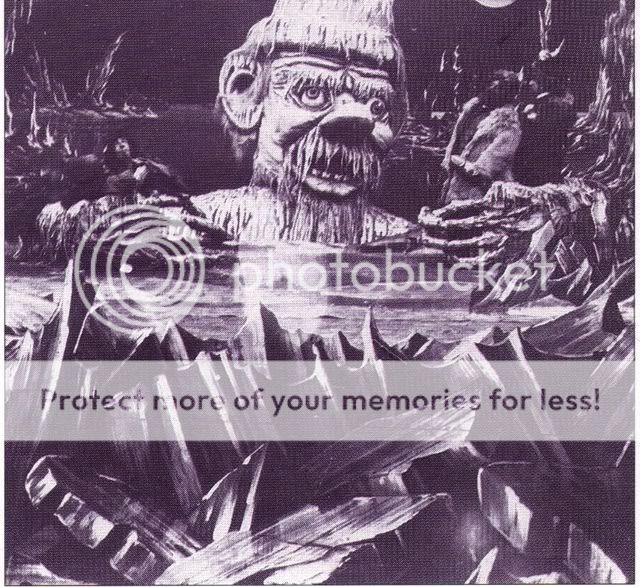

Of course this could all be the territory of standard literary fiction, but to that sturdy framework Shaw harnesses any number of narrative digressions and artistic flights of fancy. A prologue section conveys its general point about the many facets of “family” and its specific expository information about the Loonys in the abstracted fashion of Shaw’s short comics. The book’s only nod to Shaw’s more surface-weird work–drawing youngest son, introverted loser Peter, as an anthropomorphized frog–is basically a multi-hundred-page set-up for a dramatic visual punchline that works so well it literally made me gasp. Meanwhile, each family member is given memorable mini-stories and scenes to play out, from Peter’s meet-cute with local beach bunny Kat to Claire’s drunken night out on the town with Dennis’s wife Aki to Claire’s daughter Jill’s disastrous rendezvous with a friend’s hilariously sleazy soon-to-be-ex-boyfriend (it’s complicated). This also means that Bottomless Bellybutton is several different kinds of comics at once; Peter’s story, for example, is at varying times a romance, a “my first time” erotic work, (briefly) a Christopher Guest-like send-up of indie filmmaking, and in one pulse-pounding sequence toward the end, something approaching Hitchcockian suspense. Yet the book never feels scattershot or random–it all quietly reinforces Shaw’s point that family means many different things to each of the many different people inside that unit, sometimes different things at different times and sometimes different things at once.

Perhaps the best illustration of this concept is the story of Dennis, the beloved eldest child. He takes his parents’ divorce much harder than Claire (herself a divorcée) or Peter (numbed to it by his distant relationship with a father who barely conceals his lack of feeling toward him, not to mention plenty of beer and weed), and begins a pretty literal quest to find the “reason” for the divorce, thereby becoming able to prevent it. This ends up involving secret passages, X-marks-the-spot maps, and notes between his parents’ younger selves, written in elaborate codes. As Dennis grows more and more insistent and angry about the divorce, his conviction that it can be “solved” like a Lost episode mounts as well, with Shaw playfully reinforcing this sense in the reader through those parlor-game clues and boy’s-adventure tropes–and also, though who knows if this is deliberate, making Dennis an insufferable Flat-Earther straight out of a Stephen King story. By the time Dennis’s quest ends in a heatstroke-induced “revelation” that turns out to be anything but the answer he sought, it’s clear that searching for any such answer to why life works the way it does is a mug’s game. That’s not to say that any of the other coping mechanisms adopted by the characters are superior–simply that rambling off into your own directions stands just as much of a chance at finding you what you want.

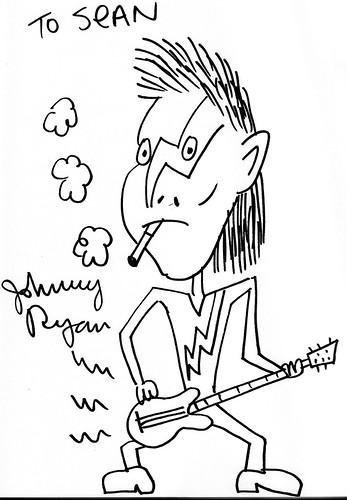

In pitching Bottomless Bellybutton to some friends who aren’t big alternative comics readers but who recently read and enjoyed Blankets, I said that the biggest difference between the two is the lack of Craig Thompson’s surface-pretty art. Shaw’s, by contrast, is deliberately uglified, particularly with those nothing-else-like-’em character designs. But I added that it’s an ugly that’s easily followed, and more to the point, easily understood. Both Blankets and Bottomless Bellybutton are about what happens when the idealized rapture of romance fades, but Bottomless takes place almost solely after the fade-out has already taken place. In this fallen world, Thompson’s vistas of snow and mandalas wouldn’t make a lot of sense. And while we do see one romance blossom, Shaw is intent on milking the tension between idealization and reality, starlit swims on the beach and premature ejaculation if you will. Impressive in the power of its gestalt, able to make judgments without seeming judgmental, and powerfully moving on more than one occasion, it’s a mature work from a young artist who with it comes fully into his own, and a deeply pleasurable, and rewarding, read.