* We’ll get to it eventually, don’t worry.

* But first: A weirdly optimistic episode, in its “Other than that, Mrs. Lincoln, how was the play” way, no? As though the whole show had heard “You Really Got Me” as Peggy got on the elevator and reacted accordingly?

* For instance: Apparently SCDP has successfully completed its public-image turnaround. Both the rival ad exec, who has no reason to brownnose Don, and the 4A guy, who has no reason to hire Lane, say how impressed they are. Dunlop basically does the same thing by seeking the agency out rather than vice versa. The mood is reflected among every non-Lane partner.

* What’s more, Don’s got the fire in his belly again, to an alarming, almost monstrous degree. For the first time in ages he seems like the kind of man Connie Hilton would admire, a guy determined to shoot for the moon.

* And he didn’t need to sacrifice his skill with a pitch in this attempt to make big things happen again. Bulldozing Ed Baxter was brilliant lateral thinking, and moreover Don’s position of privilege allows him to pull that kind of thing off where Peggy failed in the Heinz baked beans meeting earlier in the season.

* Nor did he have to ditch his newfound kindness and empathy to make it happen. He may not have been able to pull Lane out of his nosedive, but he gave Lane nearly the exact same advice he gave Peggy in the hospital long long ago — proof he truly did care about the man and didn’t want to see him hurt any worse. He may have given Glen a lift back to school in order to have a nice long car ride to clear his head, but he saw that the kid was hurting and did his best to help. He may not have been able to bring himself to talk to Megan about Lane’s death just yet, but he was as warm and kind to her as he could be without getting into it.

* (And it’s worth noting he’s still legitimately pissed about what happened with Joan. No relief that he didn’t have to make decision himself — just anger at his partners for going against his wishes and putting his friend in such an awful position. And at her, too, it needs to be said.)

* I remain impressed and delighted with the Don/Megan relationship, by the way. He comes home and she blasts him for not calling, reading all sorts of disrespect into it — she drops it right away when he tells her what he’d been through, and from then on out it’s all sweet mutual gestures like holding hands and gently ribbing him for drinking his way through the problem. They’re the best, man!

* Like Don alleges Lane felt when the truth came out, Sally and Glen are relieved to mutually discover they don’t like each other in that way. How much better to admit it than to force yourselves to go through the motions in hopes of making it true. (I also got a nice LOL when Sally asked Glen what he wanted to do now that they had the apartment and the morning to themselves, and his was response was basically “duh–the Museum of Natural History!” I had some empty-house free-morning moments with lady friends myself when I was Glen’s age, and I had no interest going to no motherfucking museum, that’s for sure.)

* Even Betty got a nice warm moment of validation, when Sally ran home to her (despite spending an entire episode basically wishing she didn’t exist) for comfort after her Sansa Stark moment. Of course, being Betty, she converts this into an opportunity to gloat over Megan (something Megan either doesn’t notice or doesn’t give a shit about, to her credit either way), and it’s unclear from her face whether she’s capable of processing momentary closeness with her estranged daughter through any lens other than her own narcissism. But we can hope!

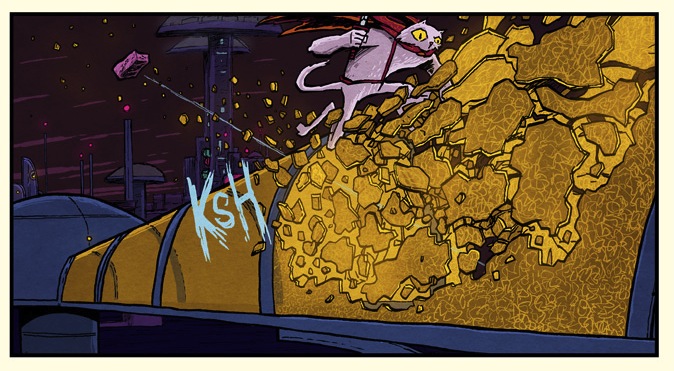

* On a slightly darker but no less delightful note: Ken Cosgrove, thou art avenged! Ken effortlessly kneecaps Pete Campbell after all this time, at last getting his revenge for the way Pete made him eat shit when he first (re)joined the new agency. When you think about it, it makes perfect sense that a guy who writes science fiction short stories under a series of pseudonyms has no problem waiting a long time for his moment in the sun — and when he saw it, he took it, with the same smiling self-confidence and security with which he does everything else. He’s actually succeeded in being what all the other people at SCDP torture themselves into trying to be.

* Great Sally moment #1: Oh, fun, fighting with Mom about food! Am I right, ladies??

* Great Sally moment #2: “I wanted to know if you would have any problem with me strangling Sally.” “Should we be having this conversation on the phone?” I laughed really hard at that one.

* Great Sally moment #3: filling that coffee cup with sugar. Sweets to the sweet.

* “Why do we do this? I don’t like what we’re doing. I’m tired of this piddly shit.” Ha, I thought Don was going existential on us — turns out he just wants bigger accounts. Well, that’s something. As Roger tells us (Great Roger moment #1), enlightenment wears off.

* Great Roger moment #2: “She’d never had room service before. It’s too easy.”

* Great Roger moment #3: Detonating Don’s months-long Ed Baxter-based impasse with a tossed-off insult: “You let that wax figurine discourage you?”

* Great Roger moment #4: “I don’t want it to sound rehearsed.” “No danger of that.”

* Great Roger moment #5: No one does “watching in slightly slackjawed, mildly dazed amazement as someone else walks away after doing something surprising” like John Slattery does.

* Nothing convinced me more of the finality and seriousness of Lane’s suicide attempt than when he broke his glasses in half. As a glasses-wearing person I can’t even think of doing that. That’s just destroying your ability to interface with the entire world.

* Don’s confrontation with Lane was excruciating on any number of levels. He’s firing a man for forging a signature he himself has been forging for decades. He’s firing a man for breach of trust in a company whose trust he breaches every day just by showing up. He’s offering to keep Lane’s secret but threatening to expose it should Lane force him despite having a huge secret of his own. And as we see a few minutes later, he’s reprimanding Lane for not coming forward with the problem despite having kept secret Ed Baxter’s revelation that the Lucky Strike letter sunk the agency with the big boys. The way Jon Hamm plays it, it’s clear Don’s acutely, painfully aware of all of this, but has to do it anyway. I kept waiting to see if this had weaponized Lane in some way, made him capable of destroying Don in return. I’m glad it didn’t. I wish it did.

* The car won’t start. Rimshot! In all seriousness the buildup and follow-through of Lane’s death by Jaguar was the show at its most Sopranos, which is to say the show at its best.

* I want to point out how exquisitely staged the discovery of Lane’s body was. Listen to the already mounting panic in Joan’s words as she goes next door to tell the guys, despite her best efforts to be calm: “I think something’s terribly wrong in Mr. Pryce’s office.” Watch as all the sight gags involving characters peering over glass to spy on other characters get transformed into a way to glimpse something horrible. Look at the empty office in broad daylight. Endure the intensely awful intimacy of Pete, Roger, and Don taking him down off the door. Watch Don’s face as he realizes a second man has now hanged himself because of something Don did, or failed to do — crushing childlike sadness.

* “I suppose you’d rather I imagine you bouncing on the sand in some obscene bikini.” Lane can’t help but befoul even the nicest thing in his worklife on his way out the door. Bon voyage indeed.

* A coldly beautiful snow falls, a figurine of the Statue of Liberty buried the frame. Sure, why not.

* Orange alert: The lining of Glen’s coat. Joan’s collar. The couch on which Pete, Harry, and Ken climb to see inside Lane’s office. Lane’s Mets pennant.

* So here are your Zoroastrian competing philosophies: “The next thing will be better, because it always is” versus “What is happiness? It’s a moment before you need more happiness!” Or to flip it, “Why does everything turn out crappy?” versus getting to drive a grown-up’s fancy car all the way home. Note which one the show ends with (eliciting crazy-person peals of laughter from me, by the way — laughter of relief). The nonsense Don’s been selling for years about a car or a Kodak being the key to a fulfilling life turns out to be true, in this very limited scenario at least. At last, something beautiful you can truly own.