Forecasting The Winds of Winter, Part 1: The North

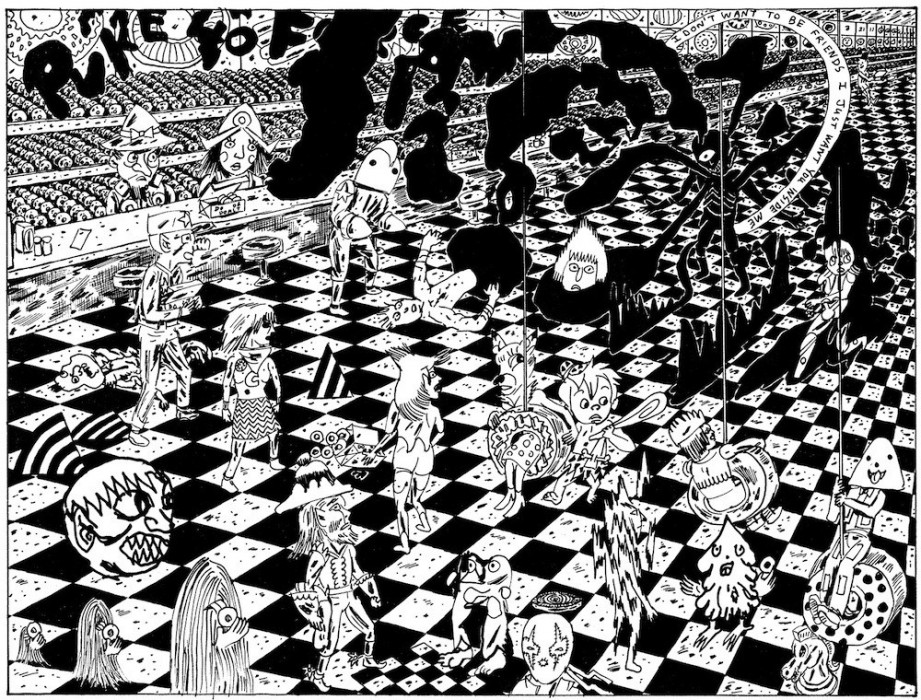

If fools rush in where angels fear to tread, then we’re about to pull a Patchface: We’re foolishly forecasting the events of The Winds of Winter in our new episode! The start of a series, this installment sees us attempting to predict what’s in store for the North in volume six of A Song of Ice and Fire. What fate awaits our POV characters—Bran, Davos, Melisandre, Asha, Theon, and of course Jon Snow? How will things shake out for supporting characters like Rickon, Osha, Hodor, Tormund Giantsbane, Wyman Manderly, the Reeds, and the Boltons? What will happen at Hardhome, Winterfell, the Wall? Like everyone who isn’t George R.R. Martin, we have no freaking idea, but it’s fun to guess, and our best guesses await! (NOTE: We do refer on occasion to the TWoW preview chapters Martin has published or read aloud, so be warned!)

But wait, there’s more! This episode also includes the formal announcement of two new fundraising drives for the podcast. The first is our new Patreon page, where you can pledge to pitch in a few dollars a month to help keep the podcast running. The podcast will always be free, but even a little money per month will make it easier for us to record more frequently and with better equipment. There are also some cool goals and rewards, so please check it out!

Our second fundraiser involves a more urgent concern: Sean’s laptop screen was recently shattered in a mishap involving his kids’ Wii controllers, and replacing it is an expensive proposition on a fulltime-freelancer’s salary. So we’re opening the coffers at our PayPal donation page. A one-time donation of any amount will help Sean revive the computer he uses to work and record—a real necessity. Again, any amount helps. Thank you so much for your generosity, and enjoy the episode!

Additional links:

Our Patreon page at patreon.com/boiledleatheraudiohour

Our PayPal donation page (also accessible via boiledleather.com)