When I was younger, I practiced vipassana meditation. Unlike my current zen habit of ‘just-sitting’, vipassana asked me to contemplate the true nature of reality by focusing on certain images that would help bring me closer to truth. One of the pertinent images that drove the Buddha towards the path of enlightenment was that of a corpse. But when you haven’t really seen a corpse that wasn’t pumped full of embalming fluid and dressed up for you, there is some serious detachment from what it really means to see inside of Death. Still, I think those hours spent drumming up morbid-but-hollow imagery were the closest I had ever gotten to actually thinking about The Abject. And I would argue it is only about as close as a S.I. swimsuit cover could take you to thinking about the truly erotic.

Bubblegum enlightenment.

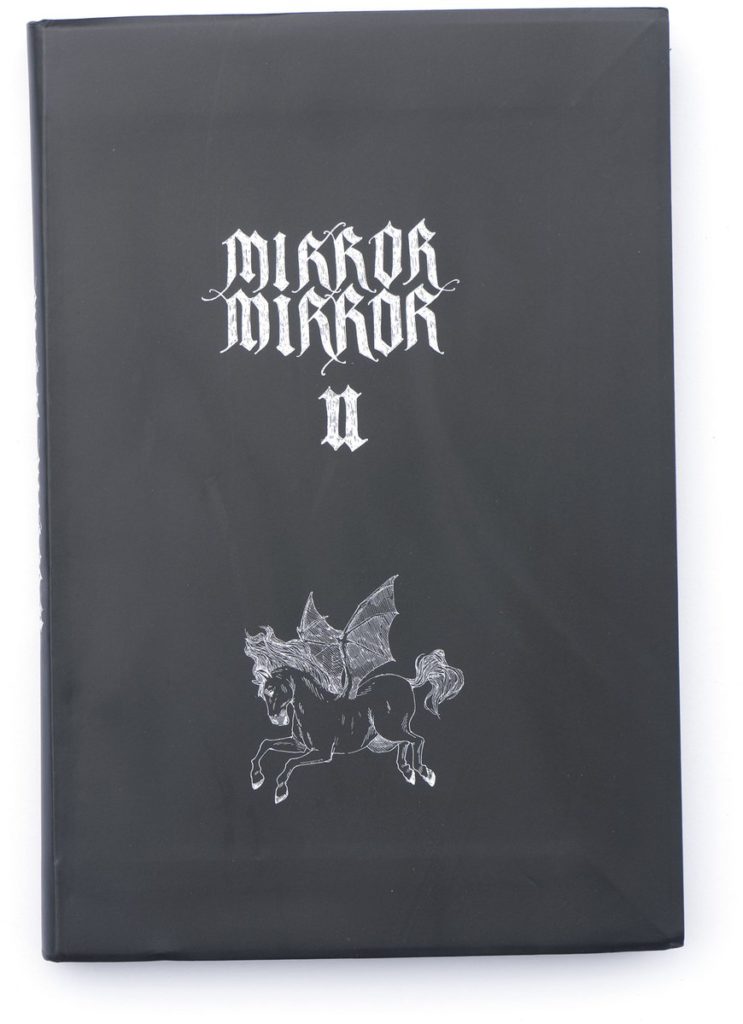

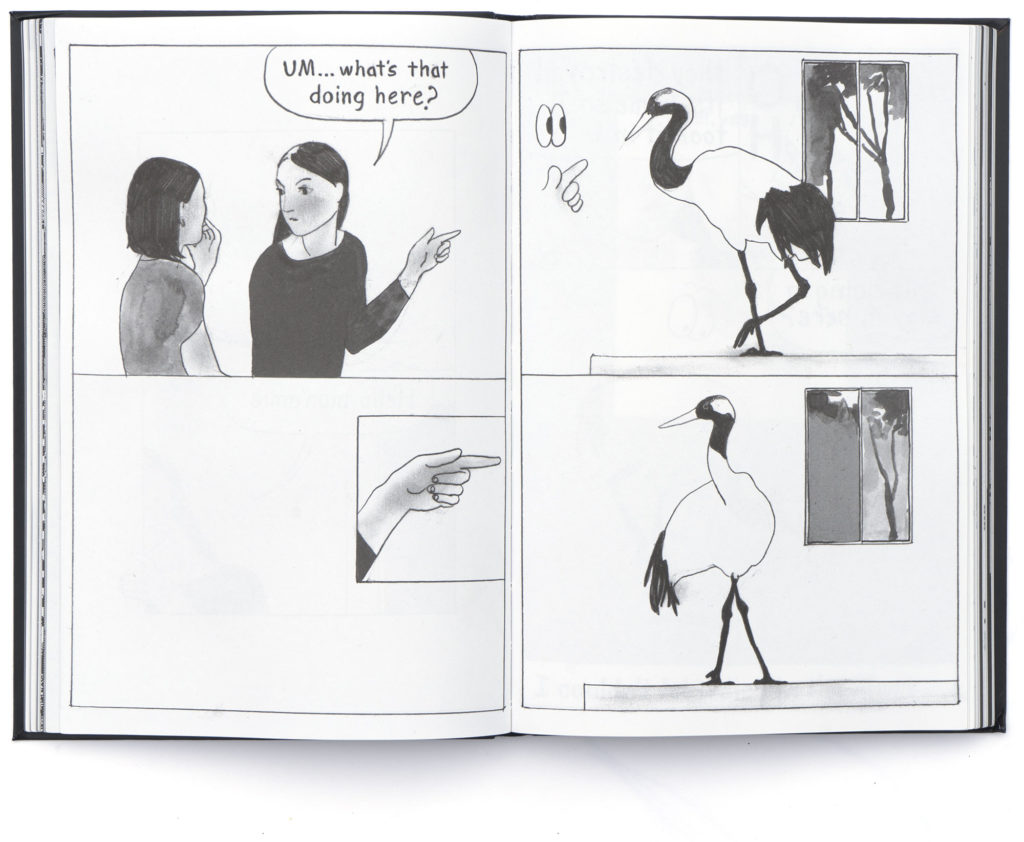

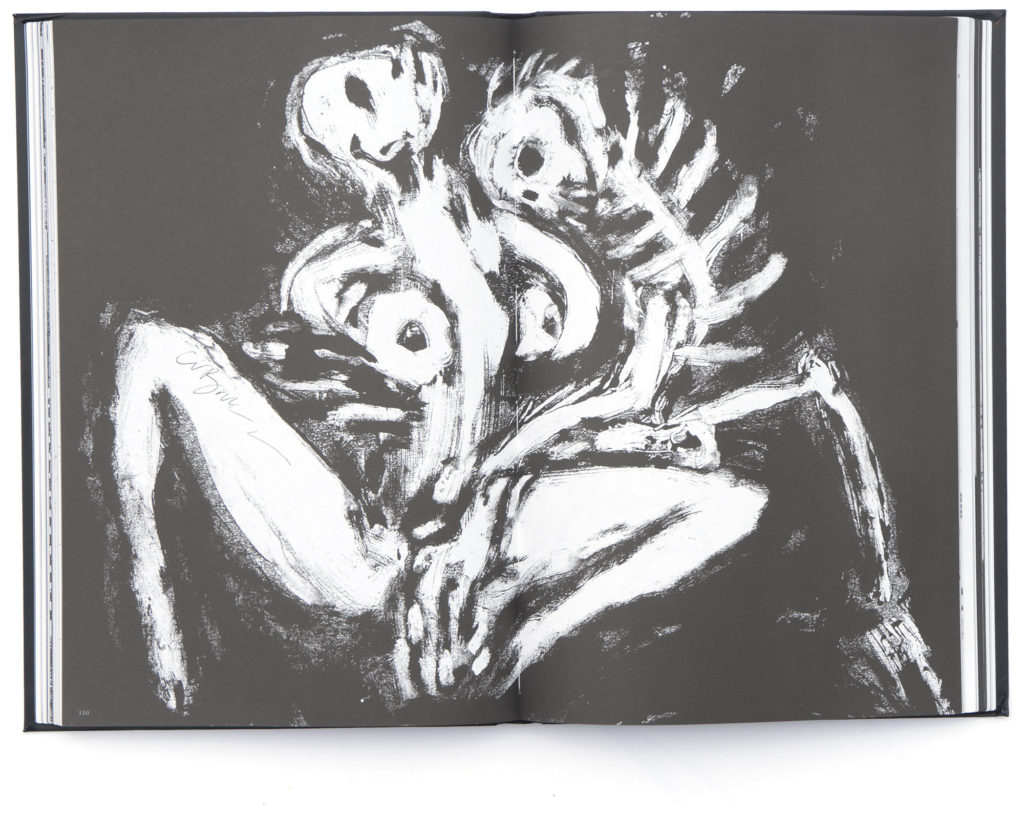

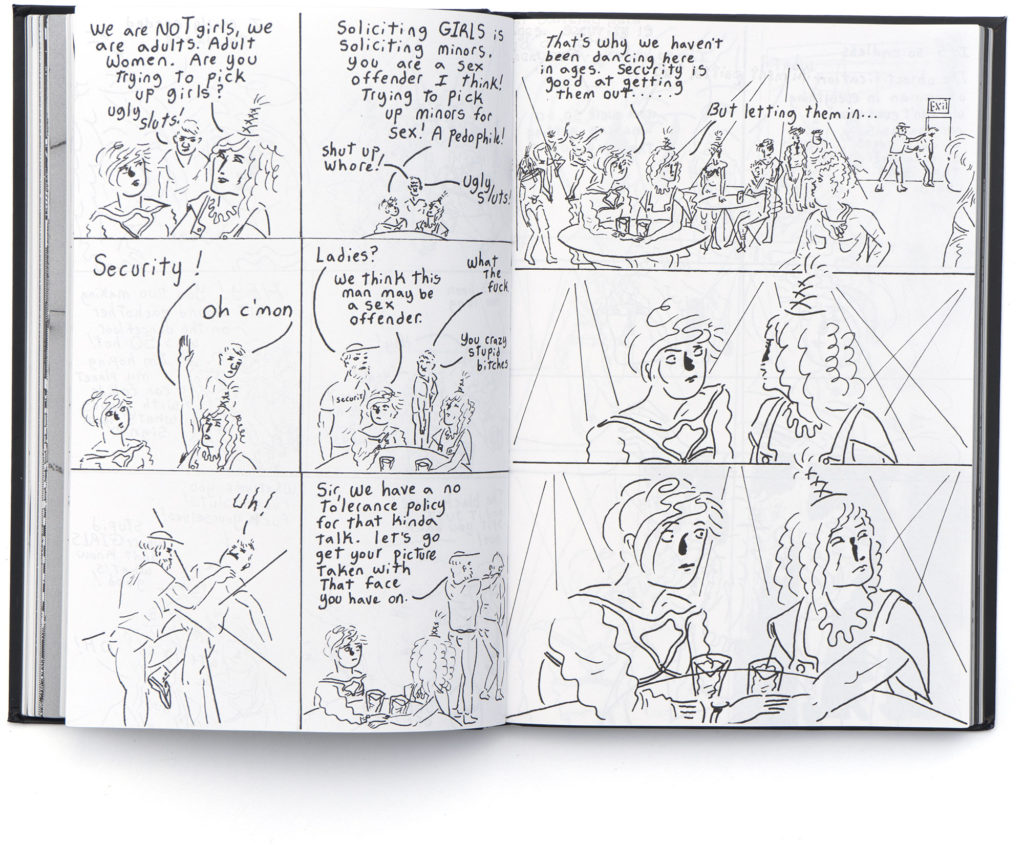

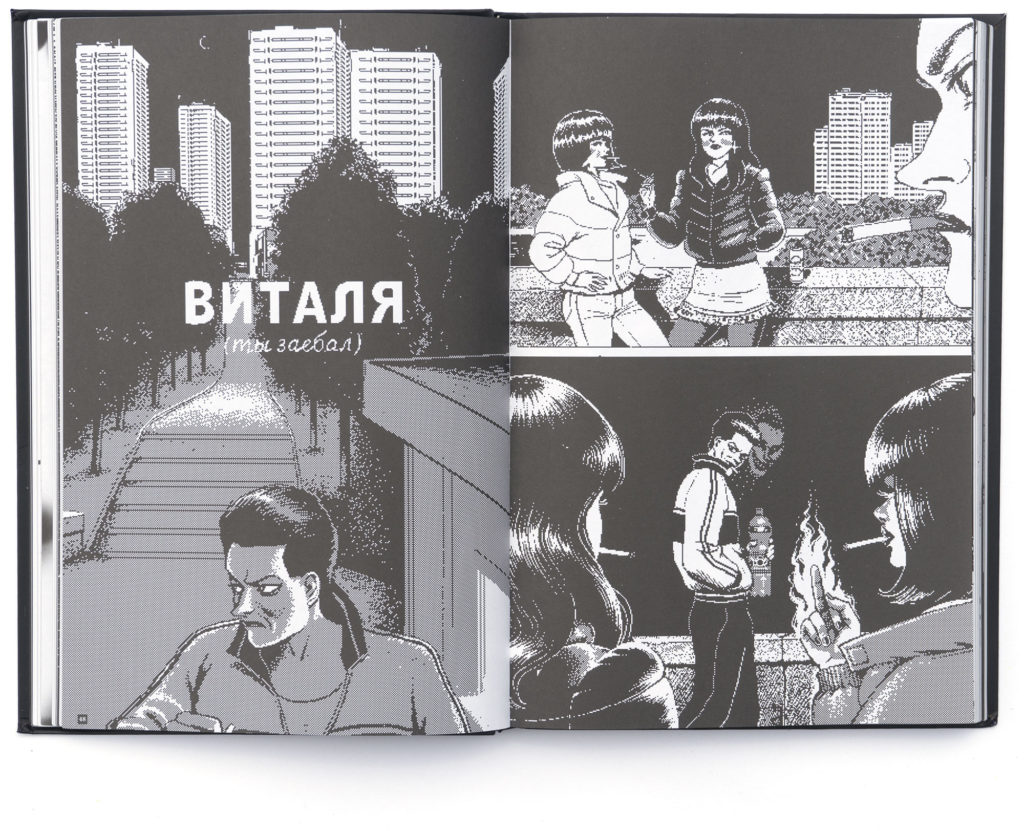

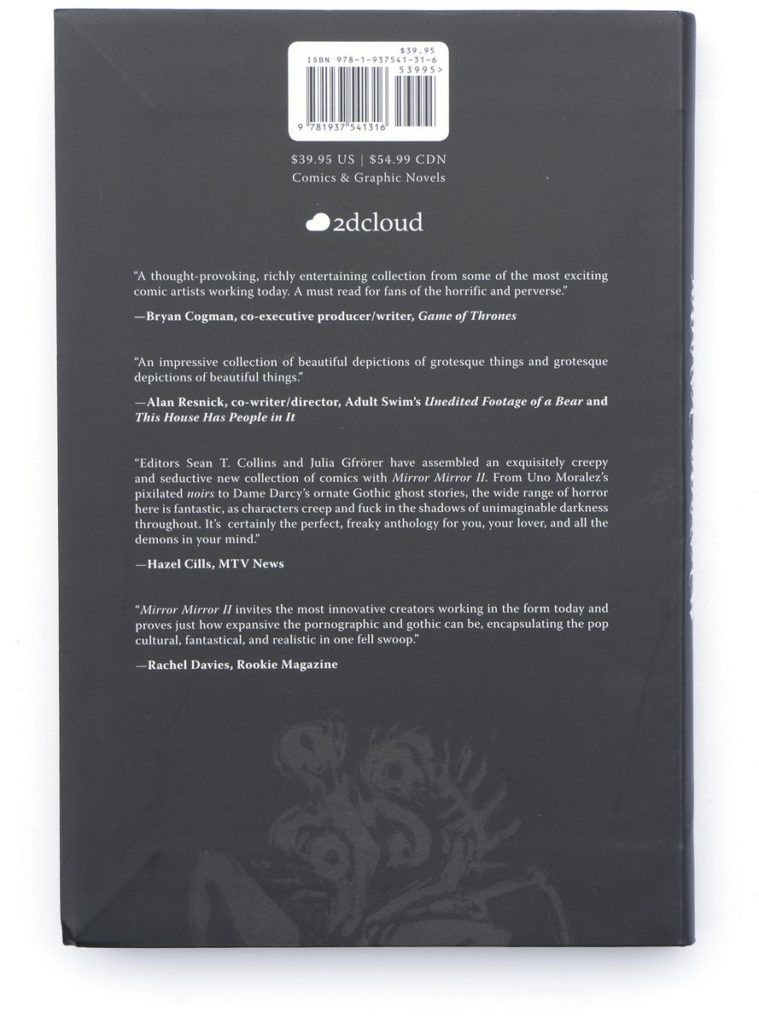

In her foreword to Mirror Mirror II, Felker-Martin asks readers like me to consider horror on a continuum with the erotic; this realm—the realm of The Abject—weaves through our humanity; from our sexuality, to the desires we bury, and back through to the very fragility of our flesh and what that means for us as everyday creatures. More than bubblegum enlightenment, this sets up a spectrum of artwork that acts as what anthology editor and contributor Julia Gfrörer calls on a recent Process Party podcast, a “sublime ritual of degradation.”

And while my girlfriend probably isn’t thrilled about the idea of watching Hellraiser, Mirror Mirror II brought at least one more person to the altar of fiction which rends flesh. Prior to this anthology, my interest in horror media generally was almost exactly ZERO. Felker-Martin’s prognosis for the reader gave me pause: “What you’re about to read will hurt you.” Why in the fuck would I want that?

[…]

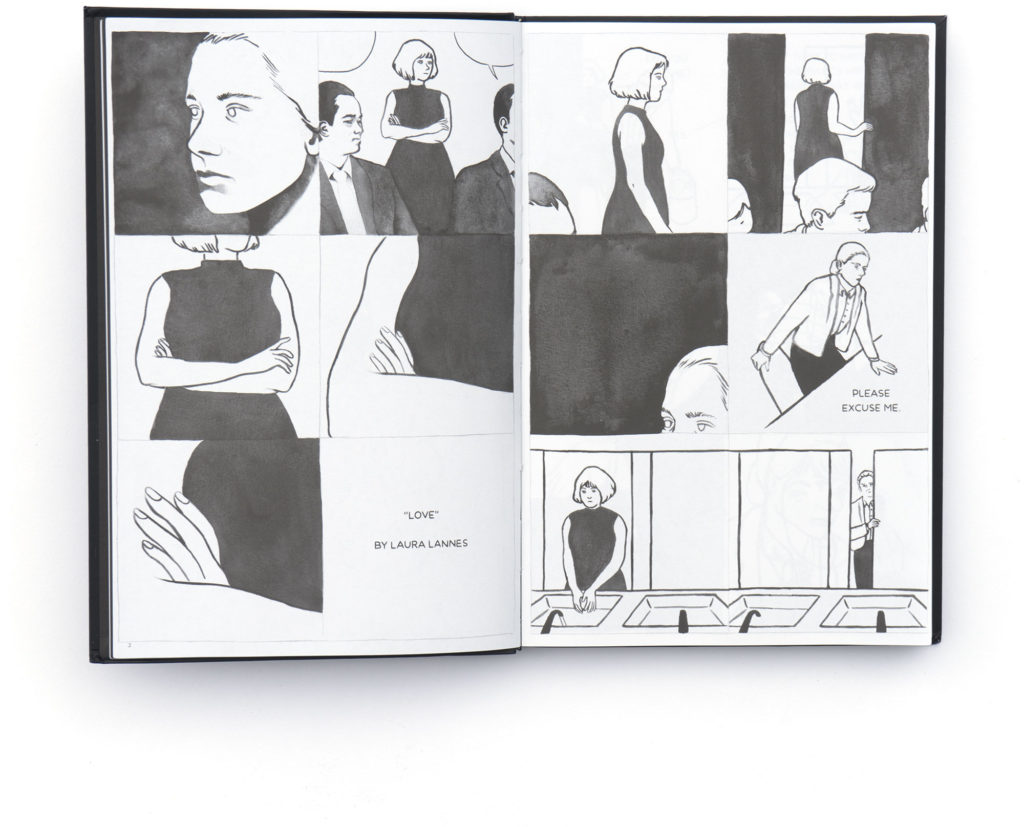

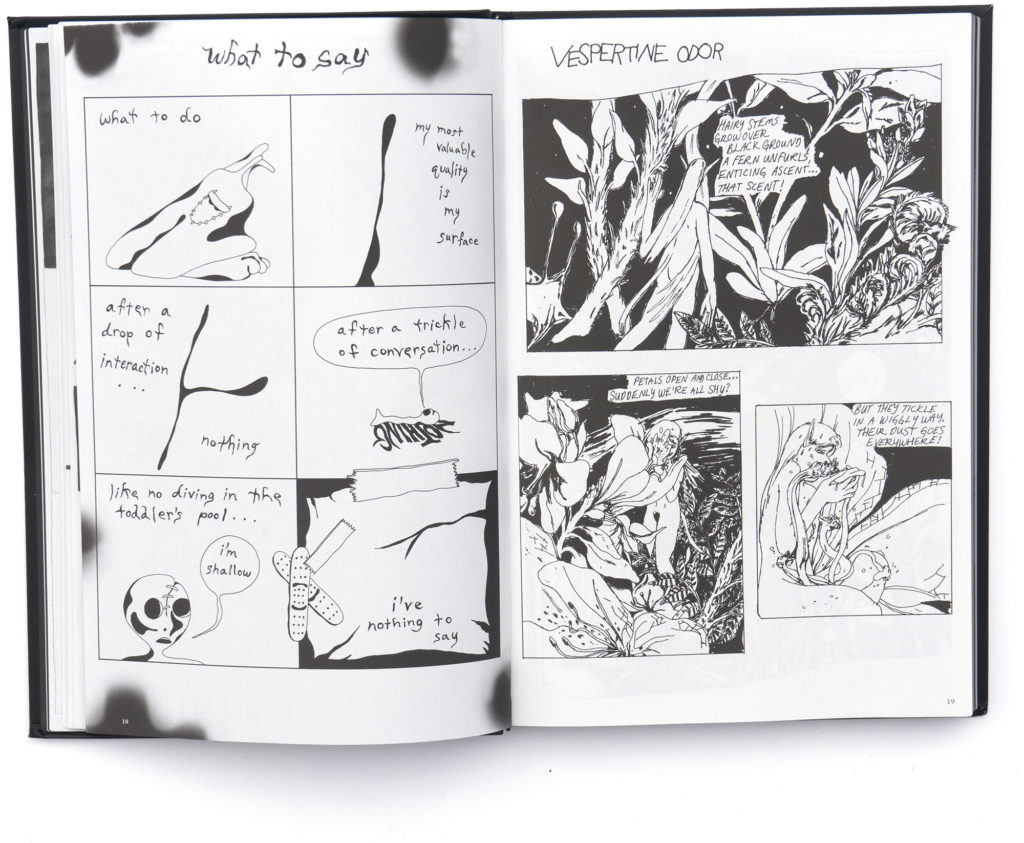

In writing this review, I first attempted to sum things up as best I could about the kind of work Mirror Mirror II is; but so many of the individual works themselves reached out and grabbed me in particular ways that I felt compelled to say something about each one.And this just kept happening.

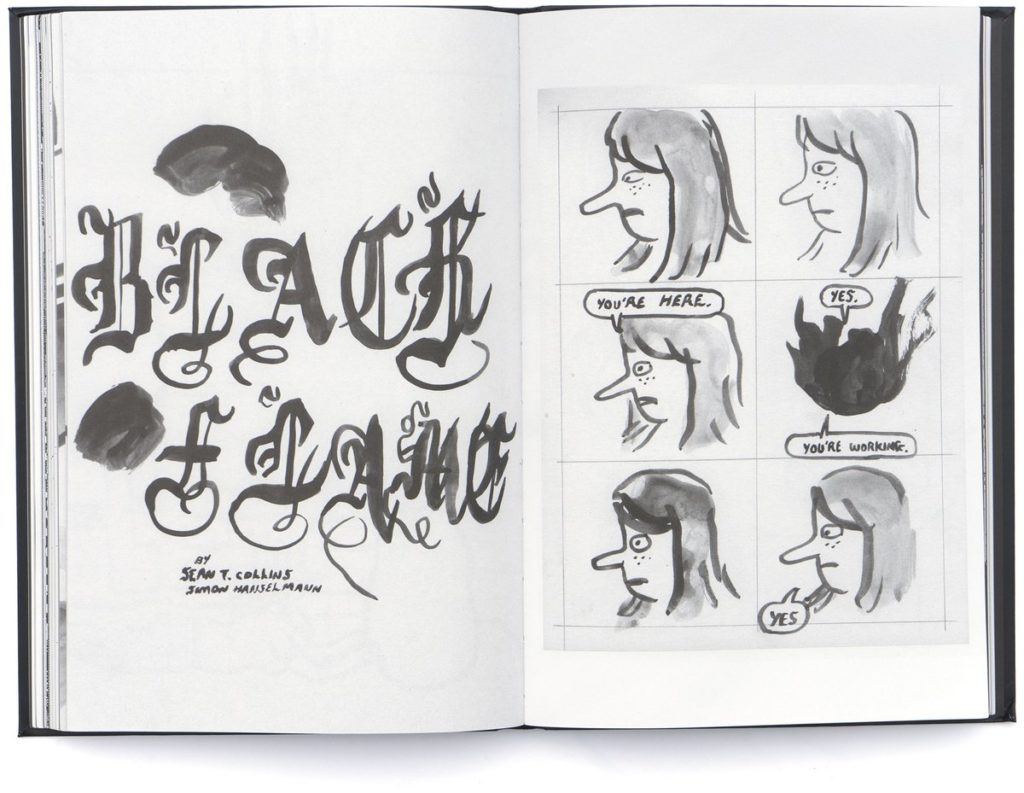

There’s still more work to talk about, from Carol Swain (shit, one of my favorite comics in the book was hers!), Al Columbia(!), Noel Freibert, Dame Darcy(!!), Mou, Uno Moralez, a murderer’s row of Clive Barker illustrations(!!!!!), a piece authored by co-editor Collins, and more. But any omissions certainly won’t haunt me as much as the work itself.

While words like “degradation” and “abject” don’t follow a straight line to “empathy” either in a thesaurus or in the minds of many people, there is obviously a broadening of perspective that comes when you are rendered vulnerable. And you cannot will yourself into vulnerability. Alone, you can only conjure decay once you are already no longer living and breathing. While you can still feel and fuck and fear, you must be led by a dark muse to a fetid clearing where a more communal sense of perversion and violation crawls between your toes. You must peer at what lies just beyond.

You must hurt.

This is the beginning and end of an absolutely extraordinary review of our book MIRROR MIRROR II by Comics Bulletin’s Austin Lanari. In between he goes in-depth on contributions by Laura Lannes, Sean Christensen, Aidan Koch, Josh Simmons, Trungles, Julia Gfrörer, and Meaghan Garvey, and basically exceeds my wildest expectations about readers getting it. I’m so grateful.