Archive for the ‘Pain Don’t Hurt’ Category

159. The future’s so bright, I gotta wear shades

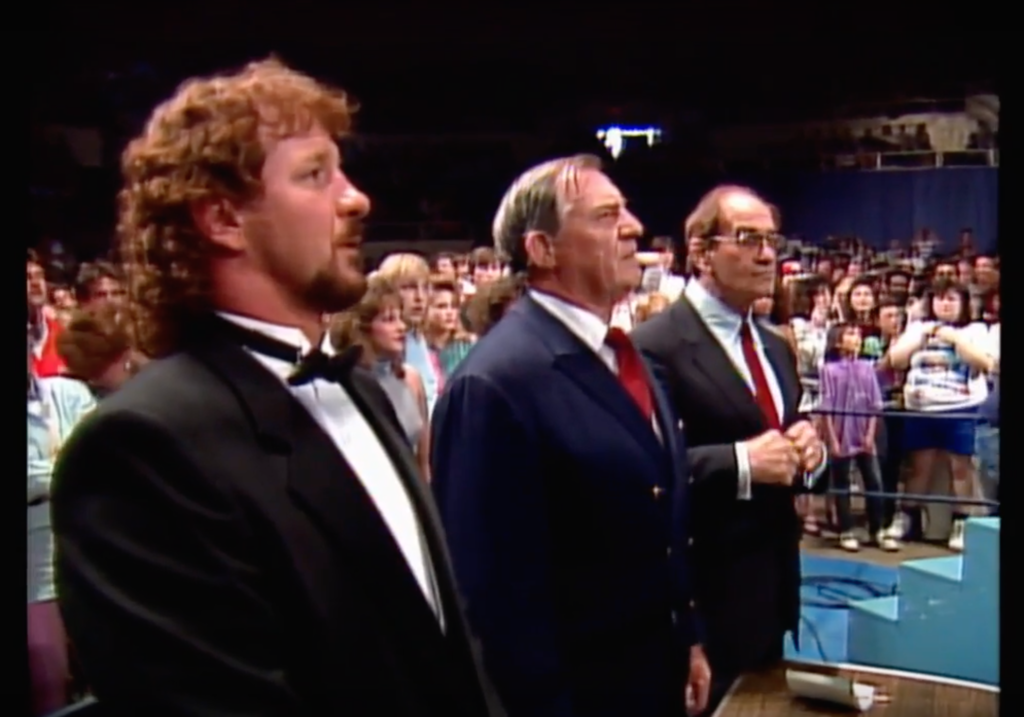

June 8, 2019When Tinker and the Bleeder are sent to collect Dalton for an audience with Brad Wesley, they do so wearing bigass aviator sunglasses. It’s sunny out, I get that. But both these men have been badly beaten recently: Tinker by the bouncers at the Double Deuce, O’Connor by Dalton at the Double Deuce, and O’Connor again by his own boss, Brad Wesley, in the driveway of the very house to which he’s delivered his quarry. You can see a bandage sticking out from under the shades, in fact. Sadly he’s not the sort to wear concealer to cover up the bruise above his lip, but he’s trying his best to look healthy, together, and intimidating in front of two men who literally beat him unconscious on consecutive days. I get why: Abusers see weakness, and they hate it, and they exploit it, and it reminds them of the anger they felt when they inflicted the damage that caused the weakness and it makes them angry all over again, and god forbid word of what’s going on gets out.

I don’t mean to take this in such a heavy direction, but consider who else is in this scene.

That’s Denise, charming horny vivacious together Denise. The night before, she hit on Dalton with no regard for subtlety whatsoever: She saw what she wanted and went for it. From a personal emotional perspective it’s one of the most impressive things anyone does with anyone else in this farkakte movie, which frequently bears the same relationship to actual human interaction that Lego minifigures have to actual human hands. But it takes place in front of Jimmy, Brad’s bastard son [citation needed], who drags her strugging out of the bar, through the parking lot, and into a nearby vehicle. Jimmy gives the high sign to Ketchum and his squad of men who’ve ordered the Rooty Tooty Fresh ‘n’ Fruity at IHOP after church on Sunday move in to attempt to assassinate the man she just hit on by kicking his skull with a knife. Denise, it appears safe to assume, is brought back to Brad Wesley’s house, where he and perhaps Jimmy beat the living fucking shit out of her.

I’ll give Dalton this much regarding his conduct toward Denise, a definite character lowlight in many other regards: Seeing what Brad Wesley did to her seems to factor into his last-straw decision to react to Wesley’s overtures with open hostility. I say “seems” because he’s most visibly pissed off when Wesley brings up the fact that Dalton killed a man who’d discovered he was fucking his wife, and that could be enough. I’m just giving him the benefit of the doubt is all.

Anyway, you’ll notice no sunglasses have been afforded to Denise. No warning that Brad would be receiving company, either. She’s in the middle of an aerobics routine with music blasting when Tinker and O’Connor roll in with Dalton in tow, because getting beaten bloody by your boyfriend is no justification for an off day.

In conclusion, O’Connor and Tinker get off easy, and O’Connor gets murdered by the end of the movie. Throw some sunglasses on his corpse.

160. How to Build a Better Goon

June 9, 2019Ketchum is a forgettable goon. That’s just facts. I know who he is because I’ve watched Road House a million times, and you know who he is because you’re reading this series of daily essays about Road House. But it took me a long, long time, and many, many viewings, to put Ketchum together, as it were: that he drives the monster truck any time it shows up; that he’s the guy who tries to kick Dalton in the head with the knife in his boot and gets his ass kicked instead; that he’s the man who kills Wade Garrett, as evidenced by his retrieval of the knife used to kill him and insertion of that knife into a custom sheath on his hip; that he’s the last goon to tangle with Dalton hand to hand; that his name is Ketchum.

Alone among the goons present for the climax of the film, no one even says his name in the movie, a privilege afforded to Pat McGurn, Morgan, O’Connor, Tinker, and Jimmy. I’ve made a fuss about this over the past few months, alleging that it’s one of the reasons he’s so forgettable. But I’ve been thinking about that assertion lately, because I don’t think it has to be that way.

Consider the orcs.

Remember these handsome fellas? Sure you do. That’s Lurtz, Grishnakh, and Gothmog, from Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. No one says their names in the movies. No one says any orc’s name in the movies. For that matter, Lurtz is a made-up name for a brand-new character the filmmakers introduced, and Gothmog is simply their best guess as to what a Mordor commander from the books whose species isn’t even specified by Tolkien might be like.

But if you’ve watched those movies recently, or if you find them memorable at all, you probably recall them as the uruk-hai leader with the Ariana Grande hairstyle whose head gets chopped off by Aragorn after a big fight, the raspy-voiced weasel who tries to hunt and kill Merry and Pippin before Treebeard squishes him, and the leader of the orc assault on Minas Tirith with the big puffy pink face. You remember how they look, how they sound, and what they do, because Jackson and company made a big point of giving them memorable introductions, isolating them with distinct camerawork (closeups, angles, whatever the case), and having them do their most memorable stuff right there for all to see. Lurtz was created to give the uruk-hai chasing the Fellowship a distinctive leadership figure so the film’s climax would work as such. It’s a far cry from the aggressively nondescript Ketchum first showing up as a non-speaking background character wearing face-masking sunglasses during the Bleeder scene and eventually killing Road House‘s secondary protagonist off-screen.

For that matter, it’s a far cry from these fellows.

Karpis and Mountain are also never named. They’re only shown in close-up in couple of scenes apiece; in Mountain’s case, one of those scenes is a pool party (in which Karpis appears in the background). Neither of them make it to the film’s final reel but it’s not because they get killed—they simply stop showing up, because that’s how Road House rolls.

But you remember them, right? They each have a distinctive look, with Karpis’s clothes from the Bun E. Carlos collection and Mountain’s sheer size. They each do something interesting: Karpis stares down Dalton, and Mountain dances like an idiot and later Sam Elliott tells him “I sure ain’t gonna show you my dick” before taking him down. The camera makes a point of both of them: Karpis stares right into it in closeup, while Mountain becomes the focal point as it follows Wesley and Denise into the pool party.

When it comes to differentiating your goons, bothering to say their name during the film helps, especially if you name half a dozen comparable characters during the film and run the risk of drowning the unnamed one out. (That doesn’t apply to LotR.) But you need the look, you need a distinctive action, and you need a memorable trick with the camera to make the look and the action click in the viewer’s mind. It’s a bit unfair to compare Rowdy Herrington’s work with Ketchum to Peter Jackson’s work in The Lord of the Rings, which is better at this than any other film I’ve ever seen. My point is simply, what’s in a name?

161. Terry Funk Trilogy

June 10, 2019The same year he starred as Morgan, the man who tells Patrick Swayze he’d heard he has balls big enough to fit in a dump truck, in Road House, Terry Funk was a peripheral participant in what is widely considered to be the greatest series of wrestling matches of all time.

In 1989, “Nature Boy” Ric Flair and Ricky “The Dragon” Steamboat battled back and forth for the NWA World Heavyweight Championship in three major televised events: Chi-Town Rumble, Chicago, February 20; Clash of the Champions VI, New Orleans, April 2; and the inaugural Wrestlewar, Nashville, May 7. Each match ran over half an hour of continuous wrestling, significantly more so in the case of the Clash of the Champions fight, which was a best-2-out-of-3 falls encounter. Flair was a flamboyant bleached-blonde self-styled playboy and the greatest heel in wrestling; the contrast with Steamboat, with his raven hair, his presentation as a serious martial artist and working-class family man, and the purity of his babyface goodness, sold itself.

But the wrestling formed the real narrative and set a new standard. Naitch and the Dragon chopped, stretched, tossed, and slammed the holy hell out of each other in epic back-and-forths in which each individual body part being worked on felt like a pivotal supporting character. The trilogy charted Steamboat’s upset capture of the title from longtime champion Flair in Chicago, his successful defense of the belt in a controversial finish at the Superdome, and his almost anticlimactic defeat by Flair to regain the championship in Tennessee. (They fought each other at off-air “house shows” dozens, perhaps hundreds, of times; some of these fights, by their own account as well as those of contemporary observers, were even better than the big three canonical bouts.)

These matches are available on WWE’s proprietary streaming service, and may also be located with minimal google-fu on YouTube or one of its knockoffs. You can sit and watch all three matches back to back and feel as if you’re watching an intimate epic, The Return of the King crammed into the deliberation room from 12 Angry Men. If you want to be entertained and awed by the world’s most lucrative outsider artform, I can’t recommend “the trilogy” highly enough.

I bring this up not only because I just watched the trilogy for the first time, but because Terry Funk’s presence was such a treat for a Road House mark like myself. While absent for the Chi-Town Rumble fight, he was one of two ringside commentators during CotC, as well as a judge and…let’s say “audience participant” at Wrestlewar. I’ll tell you this, fight fans: Anyone who thinks Terry Funk isn’t one hell of an actor needs to listen to and watch those last two matches.

In the first, Funk is largely an offscreen presence, and an ebullient, gracious, and sweet-natured one at that. His distinctive, soft tenor rasp provides a sense of almost childlike delight at the herculean feats of Steamboat and Flair in the ring; if “I’m just happy to be here” had a voice, it would be Terry Funk’s during this match. Where is the man who called Dalton an asshole and a dead man?

He’s biding his time until the following month, that’s where he is. That is when, while Steamboat is still exiting the arena and his prior commentary colleague Jim Ross attempts to interview the triumphant Flair in the ring, Funk awkwardly inserts himself, repeatedly congratulating the new champ. It gets weirder and rings phonier as the segment goes on, and Flair, whose display of stamina and guts during the whole titanic series of matches had largely won over the crowd at a time when the line of demarcation between heel and face was much firmer than it is today, gets pricklier. When Funk says he’d like to be the first to challenge Flair for the title, it feels inevitable, and Flair’s pushback—that there’s an entire ranking system of top contenders, all of whom were around while Funk was off hobnobbing with Sylvester Stallone in Hollywood—feels justified.

Funk, as you might have guessed, disagrees, and goes absolutely apeshit.

He suckerpunches Flair, blasts him right out of the ring, and goes to town on him with the security railing, with a table, with a chair. In one spot that’s particularly frightening now, after a few intervening decades of broken necks and CTE, he piledrives Flair’s skull directly into the tabletop, toppling the whole edifice to the ground as they collapse onto it afterwards. Throughout, Funk is so furious he actually appears to start crying, tearing off his tuxedo jacket and screaming “You think you’re better than me???” at the defenseless champion while shrieking at the aghast and angry crowd.

Less than two weeks later, on May 19, Road House debuted. Along with the Clash and Wrestlewar matches, it comprises a Terry Funk trilogy of its own.

I feel I understand Morgan the bouncer a bit better now after watching Steamboat/Flair II and Steamboat/Flair III. After his genial turn as an announcer I can see how he might have sweet-talked Frank Tilghman into hiring him, and perhaps even initially persuaded his coworkers to like him. After his psychotic rampage, I can see why no one dared to fire him despite his manifest unfitness for the job, and why Brad Wesley kept him on the payroll to protect his nephew and his investments. After both, I see why Rowdy Herrington cast the person he cast for the role. You could say that Terry Funk brought a lot to the table.

162. Kiss

June 11, 2019Dalton and Elizabeth’s first kiss is as much a kiss of acceptance as of romance. Their awkward, oddly hostile first date concluded, they have returned to the parking lot of the Double Deuce so Dalton can pick up his car to drive it back to Emmett’s ranch. They find its tires flattened and its window impaled with an uprooted stop sign. Doc, quick-witted as ever, quips “Your fan club?”

“They are devoted,” Dalton chuckles.

“You live some kind of life, Dalton.” This is delivered as a summation of the night’s conversation. Whether he’s ever been bested, ever been put down, ever wondered why, ever thought about the morality of accepting money to beat people, ever considered whether or not his nice guy act works—in seeing that ruined car Elizabeth appears to realize that these questions are moot. Dalton is a man willing to martyr himself so the kinds of people who’ll fuck up some guy’s car just for doing his job don’t get to do it to other people more vulnerable, less capable of fighting back. She heeds the stop sign, in other words, and lays her doubts to rest, for now anyway.

Dalton doesn’t know this yet. He sees his ruined car and sees, well, a ruined car. Now that part of his life has been displayed to the Doc, along with his battered body. It isn’t a pretty picture. (Not even his perfect physique is necessarily that impressive to someone who’s stapled it shut.)

“Too ugly for you,” he says. In classic Road House fashion this is a statement, not a question. He’s offering an answer of his own.

Then comes the happy surprise, the eucatastrophe, from the mouth of the Doc: “I didn’t say that.”

The kiss that follows (after some awkward seatbelt fumbling) is soft, nearly chaste, one sustained contact with the lips and then a release. It’s a benediction. So much is said with this one kiss that when the time comes for Dalton and Elizabeth to make love, neither feels the need to kiss again until the act has been consummated. To the extent that a kiss is the physical expression of intimacy, what can be more intimate than “I understand”?

163. Bad goons

June 12, 2019Call me old fashioned, but I believe that when the insane 7-Eleven franchisee who pays you to beat people up sends you to pick someone up and bring that person to him for a conversation, and that person gets up to go with you, you shouldn’t flinch like he just pulled out a gun. Yet that is certainly the reaction of Tinker and the Bleeder when, after Tinker says “Mr. Wesley wants to see you. Let’s go,” Dalton…gets up to go see Mr. Wesley.

This is the one time in the entire film when Tinker and O’Connor do a job that does not immediately go amiss, but their loser mindset has conditioned them to expect a beating no matter what. If they’d offered Dalton a handshake and he reached out to shake hands in response they’d burst out in flopsweat while pulling out a bowie knife. If they’d asked Dalton out on a date and he showed up to the date they’d shoot at him through the window of the diner.

You could chalk this up to Dalton’s martial prowess, with some justification. I mean, you can see what happened to them the last time they tangled with the cooler the moment you look at them. But I think that when it comes right down to it, Brad Wesley does not have a good eye for talent. Does he not say so himself when, following the defeat of Tinker and O’Connor and Pat McGurn in their attempt to restore the sister-son to his job at the Double Deuce, he ruefully acknowledges he should have sent Jimmy, one of two or three goons in his employ who’s actually good at his job? (Karpis very effectively trashed Red Webster’s auto shop in his sole observable mission, and while Ketchum lost in humiliating fashion in the parking-lot brawl, he winds up running over a car dealership with a monster truck and murdering Sam Elliott.)

Small wonder the purpose of this go-see is to try and hire Dalton away from the Double Deuce. Wesley can read the bruises and gashes all over his employees just as well as Dalton can, though admittedly in O’Connor’s case he’s responsible for at least as much damage himself.

But that ship has sailed. By hiring Dalton as his first act in the creation of the new Double Deuce, and also by establishing a bridge to Wade Garrett via Dalton, Frank Tilghman once again proves himself the town’s true visionary. He is a man who builds power; Wesley, who parasitically feeds off the town just as he coasts on the hard work of the founders of JC Penney and Fotomat, can only buy it piecemeal. In the time it would take him to accrue enough Tinkers and O’Connors to take down the likes of Dalton, the fight would already be lost.

165. No hay banda

June 14, 2019Essays connect. That is the fundamental aspiration of my writing in the form. Analogy, applicability, juxtaposition, recontextualization, “yes, and…”: When I’ve succeeded as an essayist it’s in using these techniques to draw meaning from the spaces between elements according to the order into which, after plucking them from their preexisting positions, I have arranged them. Essays are cohesive statements, derived from montage.

Every Road House/Mulholland Drive post I’ve put together since the idea first came to me has taken at least as much effort as writing a post does, sometimes more. I say this because I don’t want you to think these are a shortcut or a cheat, though you may anyway, or a joke, which if you know me seems somewhat less likely than the shortcut/cheat possibility. But it’s semantics, really. Even when I’m joking around in here I’m serious.

It may seem, it may be, funny to compare one of the great films ever made to one of the great bad films ever made. But even if it is, my brain doesn’t know it. After the connection first occurred to me I haven’t been able to get it out of my mind. When this kind of fire starts, it is very hard to put out.

Both movies are about a beautiful person who is new in town, who discovers love and sex with a beautiful woman with a dangerous past, who unearths corruption and violence under the surface of their new home, who dazzles onlookers with their talent, whose performance in their chosen role are echoed by the performers at the blue-neon nightclub they visit, who are threatened with annihilation by their inability to align the person they purport to be with the person they are. They retell the same myth about self-discovery and self-actualization, the great myth of the West.

Mulholland Drive destroys that myth in the end. Road House does not. Yet Mulholland Drive also lives the myth for the bulk of its length before shattering it. Perhaps Road House is best understood, then, as the adventures Betty and Rita to the Diane and Camilla death dance of our own real lives. It is the eject button, the escape hatch, the panic room for which an overwhelmed mind can reach before it destroys itself. No hay banda! It’s all a tape. Il n’est pas de orquestra! It is an illusion. Listen…

166. Details

June 15, 2019As a visual text, Road House is a chest of wonders. Look at this shot from early on in the film, on the night when Dalton first visits the Double Deuce. There he is at his familiar post, in his familiar shapeless beige jacket. There’s Pat McGurn and The Bartender Who Must Not Be Named behind him, conferring about whatever a sister-son and a working stiff who both happen to have the same job at the same place might confer about. (“So what’s it like working with Exene after the divorce? And this Mortensen kid she’s with, is he cool? Because he seems cool.”)

To the left is a power drinker, passed out on the bar; from this we can infer that Pat, ever conscious of the needs of his uncles liquor distributorship, refuses to cut off even the most obviously inebriated patrons, and most likely pressures the Nameless One into doing the same. Given the behavior of the comparatively sober customers, what does he have to lose, really.

To the right is a detail I’m just now noticing: the dry spongy exposed foam of the bar’s padding, chipped and peeled and torn away by the half-hearted vandalism of the drunk and the fixated. Back in the “everything is padded” days of restaurateurship, such artifacts of idle destructiveness were visible everywhere. I haven’t sat on an upholstered seat at an upholstered table in many a long year, but I can feel the satisfaction of ripping away a chip of covering and pulling at the porous brown stuffing underneath like my hands are doing it right now instead of typing this sentence. For all that Road House is rightfully dinged about its lack of realism, even as regards bar furniture specifically (the price of replacement tables alone from the fight about to ensue would put a normal establishment out of business), that’s some real shit.

And to the right of that? Why, that familiar fellow is none other than Brad Welsey’s own Tinker. Has he come to chat with fellow Wesleyans Pat and Morgan about the art of the goon over a few drinks when they have a moment to spare during their busy evenings of stealing from the cash register and erupting into violence over the slightest provocation? Is he additional muscle to make sure Mr. Wesley’s liquor flows without impediment? Is he simply a fan of the Jeff Healey Band? At another time during this sequence he’s seen chatting up some lovely lady; is the Double Deuce his fern bar, his Regal Beagle? Is this Tinker Tinder?

I’m reminded here of the extensive making-of documentaries included in the Lord of the Rings extended edition sets. I don’t remember the exact wording offered by the heads of the various costume and design and set departments regarding their lunatic attention to detail. I do remember the gist of it, though: They would produce intricate designs for the insides of garments and scabbards or for swords that would only be seen from a distance or for rooms no one would even enter or what have you not because the audience would see them, which they knew they wouldn’t. They did so because they were creating a world for the entire production to inhabit, not just the viewer. A cast or crew member who spent a few seconds admiring the embroidery of their breeches would be that much closer to convincingly conveying the reality of a world of orcs and elves and hobbits and magic rings. Look at the shot above, really look at it, and tell me if he war between the world’s most famous bouncers and the maniac mall devleoper who keeps their bar in Jim Beam seems as much of a stretch as it did before.

167. Two pool tables

June 16, 2019There are two pool tables in the Double Deuce. There are two pool tables in Wade Garrett’s topless bar. There are two pool tables in Brad Wesley’s foyer. Yes, it seems like you can’t swing an uprooted stop sign in this movie without hitting one of every location’s two matching pool tables.

You have to respect the preparedness here, particularly on the part of Brad Wesley. Frank Tilghman and the unseen owner of the strip club might reasonably expect that patrons looking to unwind with a game of skill and chance might want to play pool in numbers sufficient to require parallel pool tables.

Wesley, though? That’s his home. His home! In his foyer where his mistress jazzercises, and his goons come to escort his nemesis. His home. The man has pool parties yes, but of an entirely different variety. And to go back to The Godfather, I can’t figure out a secondary meaning to their presence. Ceci n’est pas une orange.

Yet there they stand, the Jasper Argonath, the Pillars of the Fotomat Kings. They let all who pass between them know they have entered the realm the giver of gifts, the bestower of levity and liquor, the gamesmaster, building his parody of the recreations of every day folk, a grotesque satire, now perfected, the uruk-hai of billiards. Hither came Wesley, gray-haired, sullen-eyed, cigar in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the JC Penneys of the Earth under his sandalled feet.

168. At the center of it all

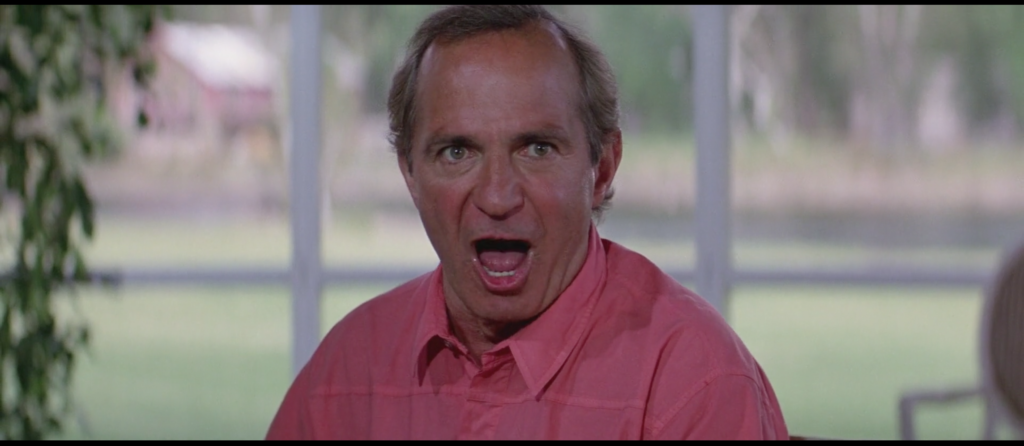

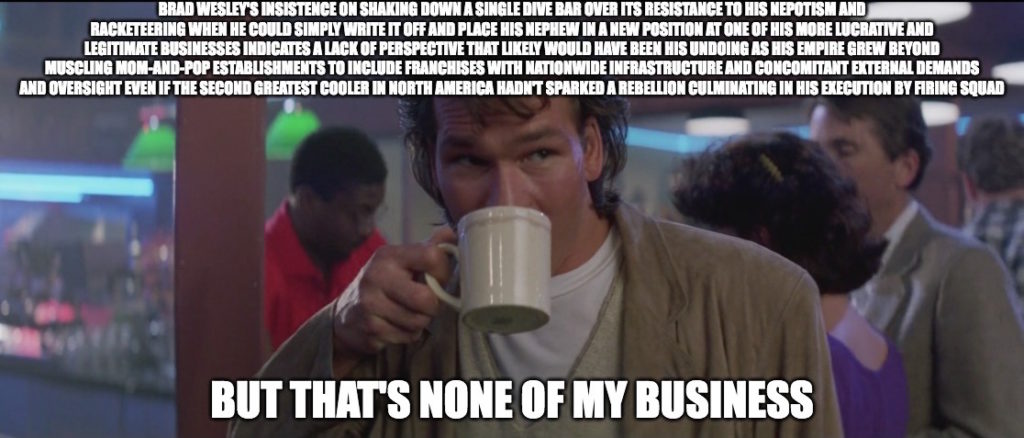

June 17, 2019The speech in which Brad Wesley touts his accomplishments as a captain of industry to Dalton over breakfast and a Bloody Mary, revealing all of those accomplishments to involve the local establishment of downscale retail chains, is memorable for the obvious reason that this film’s chief antagonist says the sentence “Christ, JC Penney is comin’ here because of me!”

But that is not the only reason it stands out. Watch how cinematographer Dean Cundey (Jurassic Park, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Back to the Future, The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China, The Fog, Escape from New York) established Brad Wesley’s centrality to his own narrative by making him the center of the shot in which he spells out that narrative.

As Wesley rattles off his life story—coming up the hard way on the streets of Chicago, arriving in this nothing of a town after Korea, building it up into an empire of Fotomats, amassing both popular acclaim and a fortune in cash—the camera follows Dalton as he walks around Wesley at the perimeter of the round room in which he sits eating at a round table. It focuses on Dalton at the beginning of the journey, shifts to Wesley near the midpoint, and pulls back to Dalton at journey’s end. Their relative positions in the frame shift as well: Wesley starts at the left and winds up at the right, while Dalton does the opposite.

What is the purpose of this perspectival pas de deux, this theater in the roundhouse? To visually convey Wesley’s narcissism and his delusions of grandeur (which in the world of the film can be passed off for actual grandeur in a pinch). To emphasize the wary, hunter/hunted relationship between Dalton and Wesley, with their shifting focus and placement in the frame making it difficult to ascertain who is the predator and who is the prey. To show off the fancy house the locations team secured for the production. To give Ben Gazzara a platform on which to declaim without so much as having to stop eating his scrambled eggs. It is a truly accomplished shot, in the sense that it accomplishes a great deal. Is it any surprise that, depending on how one counts the opening and closing credits rolling over live band performances, it is at or near the exact center of the film?

169. No Country for Poptimism

June 18, 2019“Will you shut that shit off?!” Brad Wesley yells. The “you” is unidentified, although Tinker and O’Connor snap to and head in the direction of the source of the problem. The problem is the upbeat ’80s dance-pop Wesley’s abused girlfriend Denise is blasting while she exercises, which she does with Fondaesque brio despite the bruises covering her face, neck, and chest, and the ensuing shame that causes her to cover up when Dalton sees. The source of the problem is therefore Denise, who’s playing the music in the first place. “I can’t listen to that crap,” Wesley explains to Dalton as his goons force his girlfriend to turn the brisk, bright, twitterpated tune off. “It’s got no heart!” Or balls, if you prefer, since that’s the body part to which Wesley later refers when he orders a command performance from Cody at the Double Deuce. During that performance, Denise is prompted to get on stage and strip, which she does with talent and enthusiasm. Then it’s Dalton’s turn to complain about Denise’s homage to Euterpe and Terpsichore. He refers to her as a dog who should be kept on a leash.

To the characteristically awful Wesley and the uncharacteristically mean-spirited Dalton, there’s nothing more aggravating than a woman enjoying art on anything approaching her own terms, even if it’s while working out to shake off the beating she received the night before, even if it’s taking off her clothes in front of a room full of baying strangers not for her own sake or her own financial health but to aid her abuser in his weird power trip. Music that lacks roots-rock authenticity, dancing that sexualizes the woman dancing with insufficient deference to the concerns of the man watching—these grave injustices must be stopped.

If Brad Wesley and James Dalton weren’t locked in a life-and-death struggle over a bar, they’d write one hell of a Black Mirror episode.

170. Grandpa Wesley

June 19, 2019At least I assume it’s Grandpa Wesley; it’s hard to imagine Brad Wesley celebrating his matrilineal anything, even his kindly Pep-Pep. What’s for certain is that the black and white portrait on a table in his breakfast room (at least I assume it’s his breakfast room; a man of Wesley’s pretensions to feudalism almost certainly has a long oak table with high-backed chairs somewhere around that hideous house) is a portrait of his grandfather, as he announces without looking up from his breakfast when Dalton pauses in front of it.

“Looks like an important man,” Dalton says.

“He was an asshole,” Wesley replies.

This is one of my favorite stupid exchanges in the movie for a variety of reasons. Judging from the not just conciliatory but outright deferential tone Dalton adopts when he proclaims Grandfather’s importance—the “looks like” is just a turn of phrase, you can hear in his voice he’s quite certain it must be so—it’s quite possible that this was the last opportunity for peace in our time between the two most lethal men in Jasper, Missouri.

Despite enduring multiple physical assaults and murder attempts, despite seeing what Brad Wesley does to the woman in his life, this is Dalton attempting to meet Wesley where he lives, no longer just literally but emotionally as well. Surely, surely he can get this crazy old bastard to wax nostalgic about the lessons Papaw taught him, tough but fair no doubt, thunder in his voice but warmth in his heart, taught me the value of a dollar, when you forgive your enemies you create friends, you and me Dalton we’re not so very different are we?, you can hear it all play out in your mind just as clearly as Dalton could. Who would expect Wesley to grab hold of the proffered conversational life preserver long enough only to stick his ass into the middle and use it as a makeshift floating toilet before sending it bobbing on back? Not even the second greatest cooler in North America, I’ll wager.

Which is why I believe this to be one of the few occasions in which Dalton’s cooler-sense fails him.

Consider: His powers of observation, of sight and sound, of the sixth sense that can tell when trouble has walked through your door in knife-augmented boots, are unmatched at this point in the film.

Then consider: Here is the room he walked through in order to reach Brad Wesley.

What about this picture suggests to you that Brad Wesley uses the dead for decoration because he misses the time when they were alive?

171. The difference

June 20, 2019I love Road House, I really do. I don’t think that could be any more obvious at this point. But there’s a difference between a movie like Road House and a movie we’d traditionally describe as a great movie. “Famous bouncer” is a difference. “Four different car/car parts salesmen” is a difference. “Major antagonists killed off-screen” is a difference. “Does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick” is a difference.

But the biggest difference, the difference that matters, is this: In a great movie, the shot of Denise putting her hand to her face to hide her bruises from her abuser’s employees and enemy would be a cornerstone, not a throwaway.

172. Lebowski (III): Korea

June 21, 2019Brad Wesley may bear a closer to resemblance to a very different captain of a very different industry from The Big Lewbowski, but in recasting the Korean War as a crucible for personal growth rather than the grotesque slaughter of a country by warring empires he has more in common with Jeffrey Lebowski than with Jackie Treehorn. (As far as we know, anyway; it’s entirely possible Jackie Treehorn froze his dick off in early 1951, leading to his belief that the brain is the biggest erogenous zone.)

When Wesley came to Jasper after Korea, he tells Dalton, there was nothing. His ambition stems, then, from a kind of horror vacui; this would account for his work in the area as a developer, entrepreneur, and establisher of the area’s first Slurpee machine, and it may stem from his experience with privation during that grim time overseas. For the Big Lebowski, Korea afforded him the chance to tell a non-sob-story sob story, about how a gentleman from the People’s Republic cost him his legs, but excuse me sir, spare me the pity and hold back the handouts, everything he’s done since is a testament to his indomitable will to achieve, legs or no.

In both cases the Korean Character-Building Exercise did precisely nothing to make either of these men worth more than a pisshole in a snowbank. Lebowski married into money, and his avant-garde artist daughter Maude allows him the fig leaf of a charitable foundation and a trophy wife to keep him from blowing her late mother’s fortune. Wesley built a mall and some strip-mall stores and hires semi-competent legbreakers to bust up auto-repair shops and dive bars to keep the locals in line. Both men wind up lying on the floor of their own palatial homes in humiliation and defeat by the end of their respective films, though Lebowski at least is still a going concern afterwards, which is more than we can say for Jasper’s JC Penney baron. The paths of glory lead but to Frank Tilghman’s shotgun and Walter Sobchak’s misdiagnosis of paraplegia.

173. And that’s tea

June 22, 2019174. Ozymandias

June 23, 2019

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

‘I brought the mall here, I got the 7-Eleven, I got the Fotomat here;

Christ, JC Penney is coming here because of me! You ask anybody, they’ll tell you!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

175. “You bet your ass I have”

June 24, 2019 About the only time I find Brad Wesley appealing as a person, not just entertaining but “ha, this guy’s alright,” is when he laughs and admits he’s robbing the town of Jasper blind. By now you know his litany of achievement: In the name of the 7-Eleven, the Fotomat, and the JC Penney, Amen. After he runs through the catechism, Dalton observes that he’s gotten rich off the locals, intending it to be a charge of parasitism delivered as a balls-and-strikes observation. Wesley doesn’t give half a shit how Dalton intended it, since it’s true, and he can afford to admit it. He grins and chuckles and says in Ben Gazzara’s bullfrog rumble “You bet your ass I have.” He goes on from there, announcing he’s going to get richer, that acquisitive wealth is his destiny, that he’s gathering unto him—he says “gather unto me” in so many words, amazingly—what is his. But that’s the whip cream and the sprinkles and the hot fudge and the maraschino cherry on top. The real banana split of the thing here is straight-up laughing at a guy’s attempt to own him for making money by taking it from other people and going “yeah, and?” You don’t need to admire what he’s doing to appreciate the well-deserved self-confidence with which he’s doing it. I hear Dalton’s braggadocio when he talks to his assembled bouncers about how it’s his way or the high way, with none of the “well gee I suspect it’s always been that way, when a feller earns hisself a degree from NYU and needs to make a livin'” faux humility he serves up elsewhere. I hear my talented and brilliant friends when they’re like “Fuck off, I’m talented and brilliant and deserve to be recognized as such,” one of my favorite things that any of my talented and brilliant friends ever do. They are, and they do, and others should indeed fuck off. Unfortunately for all concerned Brad Wesley isn’t a TV critic or a cartoonist, he’s a gangster who’s willing to lie, steal, and even kill if it means Jasper gets a Sam Goody. But in this way, and possibly only this way, I like the cut of the man’s jib. Alright, this way and the way in which he swerves all over the road while singing “Sh-Boom.” Those two ways.

About the only time I find Brad Wesley appealing as a person, not just entertaining but “ha, this guy’s alright,” is when he laughs and admits he’s robbing the town of Jasper blind. By now you know his litany of achievement: In the name of the 7-Eleven, the Fotomat, and the JC Penney, Amen. After he runs through the catechism, Dalton observes that he’s gotten rich off the locals, intending it to be a charge of parasitism delivered as a balls-and-strikes observation. Wesley doesn’t give half a shit how Dalton intended it, since it’s true, and he can afford to admit it. He grins and chuckles and says in Ben Gazzara’s bullfrog rumble “You bet your ass I have.” He goes on from there, announcing he’s going to get richer, that acquisitive wealth is his destiny, that he’s gathering unto him—he says “gather unto me” in so many words, amazingly—what is his. But that’s the whip cream and the sprinkles and the hot fudge and the maraschino cherry on top. The real banana split of the thing here is straight-up laughing at a guy’s attempt to own him for making money by taking it from other people and going “yeah, and?” You don’t need to admire what he’s doing to appreciate the well-deserved self-confidence with which he’s doing it. I hear Dalton’s braggadocio when he talks to his assembled bouncers about how it’s his way or the high way, with none of the “well gee I suspect it’s always been that way, when a feller earns hisself a degree from NYU and needs to make a livin'” faux humility he serves up elsewhere. I hear my talented and brilliant friends when they’re like “Fuck off, I’m talented and brilliant and deserve to be recognized as such,” one of my favorite things that any of my talented and brilliant friends ever do. They are, and they do, and others should indeed fuck off. Unfortunately for all concerned Brad Wesley isn’t a TV critic or a cartoonist, he’s a gangster who’s willing to lie, steal, and even kill if it means Jasper gets a Sam Goody. But in this way, and possibly only this way, I like the cut of the man’s jib. Alright, this way and the way in which he swerves all over the road while singing “Sh-Boom.” Those two ways.

176. Human

June 25, 2019“Oh Christ,” says Brad Wesley to Dalton, “you get paid for beating people up! Tell me you don’t love it. Of course you do! You wouldn’t be human if you didn’t!” It’s a revealing moment for two reasons. First, it’s the third time in this scene alone that Wesley has employed his favorite blasphemous expletive. I’m going to assume that “Ben, you said ‘Christ’ three times that take, do you think we can go again” was not going to cut any ice on that particular set, so there’s that, but recall which character spreads a gospel with a wound in his side. Second, Brad Wesley’s defining characteristic of humanity is the enjoyment of establishing dominance by inflicting pain, particularly in exchange for cash. This squares with everything we know about him: hiring goons to strong-arm the other weird old men who own businesses around town, beating his girlfriend, citing his survival of “Korea” and “the streets of Chicago” as the sole points of interest in his pre-Jasper biography, festooning his home with the stuffed corpses of literally dozens of different slain animals. (Trust me, you haven’t seen the half of it.) If Dalton needed any more evidence that this is a man who cannot be negotiated with, he has it now. But third, when you turn it around in your mind, you can see it as proof that he does care about his “boys,” the goons. If getting paid to beat people up is a way to do what you love and love what you do, if it proves your essential humanity, then what a gift he has bestowed upon Jimmy, Ketchum, Karpis, O’Connor, Tinker, Morgan, Mountain, and his sister-son Pat McGurn, all of whom he pays to beat people up. For Brad so loved the goons, that he gave his only begotten cash, that whosoever worketh for him should not perish, but have everlasting life.

177. “You ask anybody, they’ll tell you!”

June 26, 2019“Christ, JC Penney is coming here because of me!” gets all the attention, and for good reason. In Road House, the archvillain, a man who employs a small army of hired thugs to blow up buildings with recalcitrant old men in them, touts the arrival of The One-Day Sale—Storewide! as his greatest accomplishment. As my own summary goes, “Road House is the story of one bouncer’s quest to free a small town from the iron fist of the guy who is on the verge of opening the area’s first JC Penney. Over half a dozen men will die for this.” So I get it.

I prefer Casino to GoodFellas. Which is not to say I fail to recognize GoodFellas as Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece of mass entertainment, which I intend as a pure compliment. It’s the movie, not the kind of movie but the movie, that makes people fall in love with cinema. It’s like if the philosopher’s stone was rock candy. It’s a towering achievement. But I prefer Casino to GoodFellas because its interests are closer to my own. It’s grandiose, spectacular, it has a machine logic behind its narrative flow, it has pitiable characters and funny characters but no likeable characters, it’s brutally soul-crushingly violent, the music is maybe even cooler than the music in GoodFellas, it reads as a rejoinder to anyone who thought GoodFellas is about how much fun it is to be in the mafia, which may well have included Scorsese himself. It’s not the colossus GoodFellas is, but it stands taller in my heart.

I’m not sure if I’d go that far in describing the line that follows the JC Penney thing, which is “Ask anybody, they’ll tell you!” because let’s be honest, “Christ, JC Penney is coming here because of me” is the sound of my soul. But do not, do not sleep on that follow-up. Travel inside Brad Wesley’s mind and look out through his eyes at the town of Jasper, Missouri, and what will you see? A bustling hive of simple little people, buzzing with excited gratitude for what Brad Wesley has done for them, awed by its magnitude, eager to spread the good news. Brad Wesley envisions Dalton driving down the main drag, stopping in one of the town’s countless hole-in-the-wall bars and greasy spoons (Jasper is where Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives manifests Guy Fieri’s id as a tulpa), sidling up to one of the Four Car Salesmen, stopping people at the doors of the Double Deuce, grabbing any man jack off the street, chatting up any swinging dick he sees and getting the same response: “Oh, the JC Penney? It were Brad Wesley what done it.” Like Boromir or Samwise Gamgee contemplating a world in which the Ring gives them Command, Brad Wesley envisions the masses roiling with department-store ecstasy from sea to shining sea, his name rolling off their tongues like glossolalia. Children by the million sing for Brad Wesley bringing JC Penney to Jasper when he comes round. I’m in love. What’s that store? I’m in love with that store.

178. Phantasmagoria

June 27, 2019“Cinema is a language. It can say things—big, abstract things. And I love that about it. I’m not always good with words. Some people are poets and have a beautiful way of saying things with words. But cinema is its own language. And with it you can say so many things, because you’ve got time and sequences. You’ve got dialogue. You’ve got music. You’ve got sound effects. You have so many tools. And you can express a feeling and a thought that can’t be conveyed any other way. It’s a magical medium. For me, it’s so beautiful to think about these pictures and sounds flowing together in time and in sequence, making something that can be done only through cinema. It’s not just words or music—it’s a whole range of elements coming together and making something that didn’t exist before. It’s telling stories. It’s devising a world, an experience, that people cannot have unless they see that film.” —from Catching the Big Fish by David Lynch