Archive for the ‘Pain Don’t Hurt’ Category

079. Son

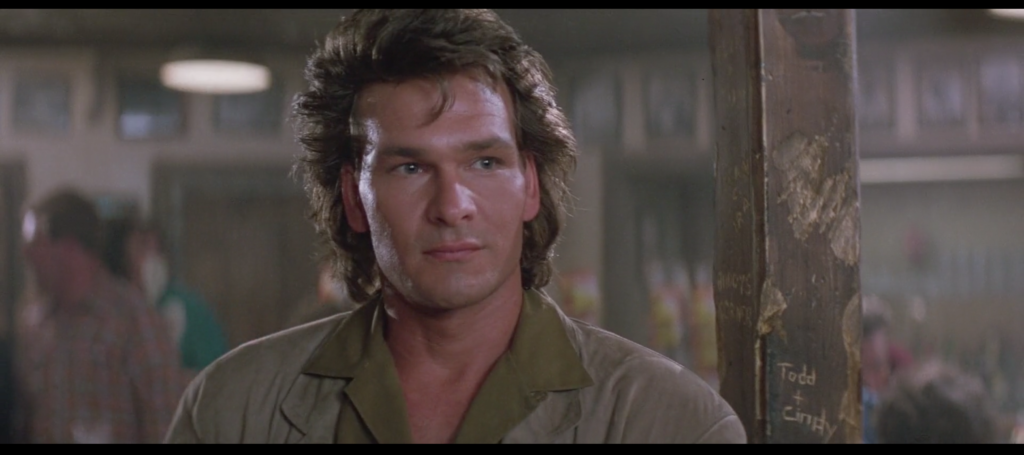

March 20, 2019O’Connor is the cornucopia of plenty of goons. Like Barry White, He’s Got So Much To Give, and like Barry White he gives it in basso profundo to boot. In addition to delivering the purest expression of contempt I’ve ever heard in cinema, in addition to getting beaten unconscious when his boss finds his excessive bleeding to be an indicator of cowardice, in addition to dressing business-cazh to every ass-kicking he attempts to give and/or winds up receiving, this poor dumb bastard somehow drills right down into the subtext of Road House and strikes black gold without even trying. My partner, the cartoonist Julia Gfrörer, told me earlier on in this process that Road House is a movie about fatherless sons and sonless fathers. And what do you know—O’Connor addresses Dalton accordingly. When he appears in the Double Deuce with Tinker and Pat McGurn to force Tilghman to re-hire the mustachioed failnephew as a bartender or face the cessation of liquor shipments, Dalton is naturally initially curious as to their intentions. After shutting up the shithead, O’Connor grins broadly and tells Dalton “Mr. Tilghman has changed his mind,” then lowers his head and looks the cooler dead in the eye and gets all serious and adds “And that’s all you need to know, son.”

Son! For context, please note that Michael Rider, the actor who plays O’Connor, is just over four months older than Patrick Swayze. Not even years, which would be goofy enough—April 1952 vs. August 1952 is what we’re talking about here. “Son” is an attempt to bigfoot Dalton by a man who believes himself to be an authority figure. It’s likely meant to belittle him, and I mean literally: Dalton is just knee-high to this towering would-be father. It’s meant to son him, in the Nicki Minaj “all these bitches is my sons” sense.

Naturally, it works out about as well for O’Connor as anything else he tries in this movie. But it does earn him this distinction: He is the only man murdered by Dalton who casts his own eventual demise in Oedipal terms. No doubt Laius was a bleeder too.

080. Dodge

March 21, 2019

If there’s anything else in the history of action cinema I’ve studied with the same open-hearted intensity I’ve applied to Road House, it’s the Tomb of Balin/Bridge of Khazad-dûm sequence from Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring. Back in the summer of 2001, in the Before Times, I was invited by New Line Cinema in my capacity as assistant editor of the Abercrombie & Fitch Quarterly, my first real job out of college (see what I mean about the Before Times?) to watch the 20 minutes or so of footage from Jackson’s first Lord of the Rings movie that had been publicly screened, initially some weeks prior at the Cannes Film Festival. Wisely the studio had selected the film’s first real action setpiece, the slobberknocker with the orcs and the cave troll in Balin’s Tomb and the flight down the crumbling staircase afterwards. Any doubts I might have harbored about the ability of Jackson, a filmmaker whom I loved for Heavenly Creatures but wasn’t sure could tamp down his manic style for Tolkien’s world, evaporated the moment the fighting began. This was a director who understood that effective action is shaped by the environment in which it’s staged, with easily understandable physical stakes for the success and failure of each blow and maneuver, relayed through camerawork that allows the eye to parse the spatial relationships between the combatants.

What’s more, and the friend I brought along with me as my plus-one to the screening room is the one who pointed this out, Jackson understood that the key to fantasy as a genre is scale, intuiting George R.R. Martin’s much-quoted dictum that we turn to fantasy “to find the colors again,” to transcend drab reality on (paraphrasing here) the wings of Icarus rather than Southwest Airlines. Neither Jackson nor Martin (nor Tolkien, nor Benioff & Weiss for that matter) felt this meant completely detaching the material from reality; on the contrary, the punishing realism of Martin’s setting and the painstaking detail of the Weta Workshop’s worldbuilding made the truly massive scope of the landmarks and lives of Westeros and Middle-earth all the more convincing.

I’ve told this story many times now, but it was specifically one of the Moria sequence’s action beats that brought this home to me. As the Fellowship flees down those gigantic, precarious stairs, orcs begin pelting them with arrows. Legolas, the Elven archer, turns and fires back at one of the distant foes. The camera travels as if mounted on the shaft, giving us an arrow’s eye view of the cave and the evil creature on the opposite end towards whom it is racing. A cut at the moment of impact switches us to a view of the same cavern from just behind and above the orc (by now struck right between the eyes and plummeting into the abyss below), angled downward toward the Fellowship on the stairs hundreds of yards away. The arrow’s flight, and our flight along with it, describes that vast space in a way a more traditional establishing shot could not. If we’d started with that over-the-shoulder shot looking down at the Fellowship we’d have gotten the picture I suppose, but we wouldn’t have been made to feel the space, the scale, the awe.

Whether to reserve the sight of the Balrog for the eventual filmgoing public or because that sight had not yet been completed I can’t recall, but the preview cut off with our final glimpse of the Fellowship escaping the stairs. The chase across the Bridge, the standoff between Gandalf and the Balrog, Gandalf’s triumph and fall, and the Fellowship’s mournful escape had to wait until the premiere. But there’s another moment with an arrow that stuck with me then and still does today. As Aragorn, the last one out of the Mines, looks back at the chasm, the rain of arrows from the orcs, who’d given the Balrog a wide berth, resumes. Viggo Mortensen, an amazing proficient action performer for a guy who had about a week of instruction before his first on-camera swordfight compared to the rest of the cast’s extensive training camp, had clearly been instructed by Jackson to act as though he was dodging arrows that were added digitally after the fact. Like a particularly generous pro wrestler he sold the hell out of it, at one point ducking so dramatically it’s like he was avoiding some big galoot’s haymaker. The desultory choreography of the move jumps out at me because Mortensen’s Aragorn is otherwise a model of physical efficiency in his fighting style, as befits a man who’s been hunted all his life and has learned that excess movement can mean the difference from ending a fight merely exhausted and ending a fight dead. It’s taken me time to come around to it but I now recognize it as the right approach for a character who’s been momentarily poleaxed by a grief he never believed he’d experience.

Anyway, at one point during the big bar-destroying fight that breaks out in Road House when a man squeezes another man’s wife’s tits without paying to kiss them as he’d appeared to agree to do, a stray bottle comes flying in Dalton’s direction and shatters against the post next to which he’s been standing and taking in the scene, and he dodges it and resumes watching in less time than it took either of the arrows described above to do their thing. This doesn’t tell us anything about the scale of the Double Deuce, the spatial relationship between Dalton and the unseen bottle-thrower, the nature of the world in which the film takes place, the emotional state of the characters, or the approach of director Rowdy Herrington toward the material. It just tells us that Dalton is so good at dodging broken glass that it doesn’t even disturb his spit-curl. And that’s all you need to know, son.

081. Don’t Throw Stones

March 22, 2019The most important thing the opening sequence of Road House wants to convey to you is not to throw stones. “Don’t throw stones,” says the man on stage at the Bandstand. “You don’t know,” he continues. “It’s not what you say, it’s what you do,” he elaborates. He then repeats for emphasis “Don’t throw stones” to conclude his statement.

Why this happens is…ah, one of the great mysteries of Road House, right up there with beginning the film in a bar that is not the titular road house, or even a road house at all.

It’s not like the man singing “Don’t Throw Stones” is Jeff Healey, lead singer of the Jeff Healey Band, who provide the live music in every subsequent scene with live music. He’s Tito Larriva, lead singer of Cruzados, the band playing here, and he’s a pretty interesting cat in and of himself, a human Wikipedia k-hole. He started his musical career as lead singer of the Plugz, an LA punk band from the general Decline of Western Civilization/Love and Rockets milieu who did the original score for Repo Man. Much of the band subsequently morphed into Cruzados, which played up their Latino roots and made a kind of Eighties coke-bloat blooz-rock thing out of it. After their breakup, Larriva eventually formed Tito & Tarantula, who provided the musical accompaniment to the Salma Hayek snake dance in From Dusk Till Dawn. Various members of the Plugz/Cruzados continuum also played with Bob Dylan on Letterman in ’84, the drummer played for Izzy Stradlin & the JuJu Hounds, Social Distortion, and Mike Ness’s solo band, and the bassist has worked with Matthew Sweet for years as well as doing various things with sundry rock and roll legends. How they wound up here has, I assume, something to do with the golden ears of music-industry macher Jimmy Iovine, founder of Interscope, co-founder of Beats by Dre, dater of Stevie Nicks, partial inspiration for “Edge of Seventeen” via his intense grief over the murder of his friend John Lennon, and billionaire, married to Liberty Ross, who’s the sister of Atticus Ross, who’s the songwriting partner of and second-ever official member of Nine Inch Nails with Trent Reznor, who once opened for Izzy Stradlin’s other band Guns n’ Roses and who co-starred with Repo Man‘s Harry Dean Stanton in Twin Peaks: The Return and spent years recording for Iovine’s label Interscope before eventually being named chief creative officer of Beats Music, which became Apple Music after Iovine and Dr. Dre sold it to Apple and became billionaires. It’s a small world after all.

<Al Swearengen voice> Anyways, </> Larriva’s face is the second face you see in close-up in Road House, beaten to the punch only by Kevin Tighe. This is an interesting first foot to put forward, not only because Tighe and Larriva’s looks are <Fifty Shades of Grey meme voice> unconventional </a>, but because Larriva isn’t even in the movie after this first scene. But Road House is a film that plays its cards close to its chest in the early going, primarily because despite the skill of the team of action-movie aces employed to make it look good, it’s written (in part by Academy Award nominee Hilary Henkin) as if the writers were randomly but repeatedly struck on the head during the process, resulting in wild miscalculations of the relative weight of what is shown on screen. The Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri are one result. Using Frank Tilghman as our entry-point character even though he’s a grinning ghoul in a bolo tie who could only read as more villainous if huffed fumes and said “baby wants to fuck” is another. Centering the whole opening sequence on a band that you’ll never see again is another.

And there is simply no way to overlook or underplay the presence of the band in this sequence, no. They won’t let you. Our first good look at Larriva, in a vest and pirate-look shirt that are striking even given the Road House fashion baseline, involves him screeching, and I mean it sounds like someone just low-blowed him, “IF YOU LOVE ME BUY ME A BIG TEE VEEEEEE” at the top of his lungs and the top of his register. He goes so hard and so high on this he literally stands on tiptoes and sings down into the mic. He coils his face back into his neck like a snake whose strike is sonic rather than physical. This requires effort, and it does not look like a pleasant effort either. So you know, kudos to Larriva and Cruzados. They left it all out on the stage, a stage they were placed on for some reason.

Now when you first watch Road House you may not realize it, but the message espoused by this song will get under your skin. I’ve found myself singing “Don’t throw stones” around the house. I’ve heard my partner doing the same. We’ve used it as shorthand for watching Road House at all, the way couples text “COAT” at each other to find out if they’re going to get laid if they come home instead of staying out with their friends.

What I’m getting at as this: This sequence is superfluous, its content is a non sequitur (not throwing stones is part of neither the Dalton Path nor the Wade Garret Way), the time spent with it is unpleasant, and the lingering impression is endearing. And here’s the thing about that as it applies to Road House, according to J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings:

“I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history – true or feigned– with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed dominion of the author.”

082. Intimacy

March 23, 2019If there’s one thing the Marvel/Netflix shows, even the ones I’m not crazy about, have been good at, it’s tying their superhero/vigilante violence to moments of physical intimacy. Sometimes this involves the main characters having sex, and from Jessica Jones and Luke Cage to Luke Cage and Misty Knight to Matt Murdock and Elektra Natchios, those scenes have been hot across the board. That’s certainly true on this show as well, from Agent Madani and Billy Russo to David “Micro” Lieberman and his wife Sarah to [the Punisher] and Beth the bartender just last episode.

At other times the violence itself is intimate. This naturally tends to be the case more for the characters who lack super-strength than for those who do, but it’s true. Watching mortal men like Matt Murdock and Frank Castle be made vulnerable by the infliction of violence on their bodies is a display of intimacy. To quote myself quoting Barbara Kruger regarding another show, “You construct intricate rituals which allow you to touch the skin of other men.” Hallway fights are an intricate ritual indeed.

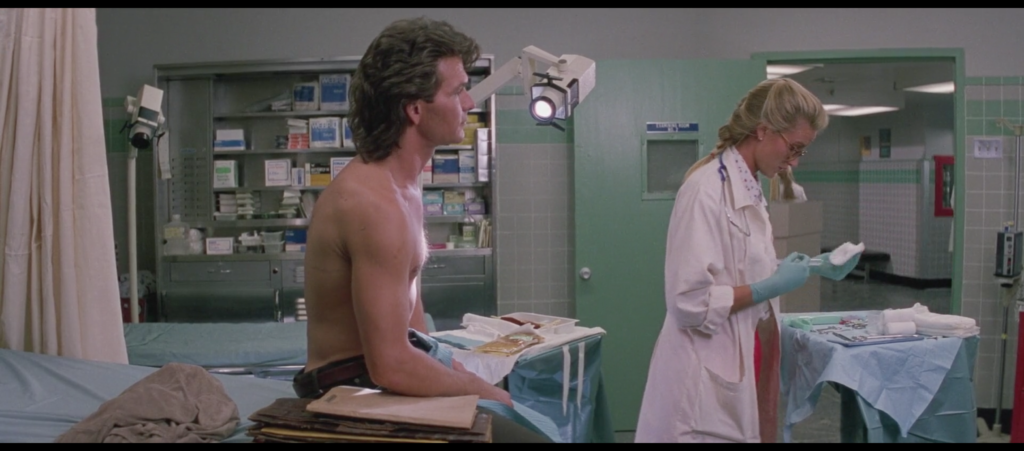

And then there are the moments of triage that occur after the battle is over. I’m thinking Luke Cage tending to Misty Knight’s mangled arm for damn near an entire episode (overlong thanks to Netflix Bloat, but still notable), or Frank Castle and Karen Page leaning into each other in an elevator after spending an entire episode trying to avoid being murdered by a mentally ill gunman. In this case it’s “Rachel” (if that is her real name), the shifty fugitive Frank’s been protecting for two episodes, removing a slug from Frank’s right buttcheek. Earlier in the episode, it’s her taking his boot off for him when he proves unable to do it himself. You see the same principle at work when Daniel Craig hugs a crying Eva Green in the shower after a killing spree in Casino Royale, or when Bruce Willis has a heart to heart with Reginald Vel Johnson while he picks shards of glass out of his bare feet in Die Hard, or even when Patrick Swayze and Kelly Lynch meet cute while she staples a knife wound in his side in my beloved Road House. Sylvester Stallone, the actor who at his best most reminds me of what Jon Bernthal does, constructed two entire franchises around the idea that there’s something interesting about watching his perfect body get beaten to shit. Moments like this make the violence real and draw those of us who’ve never experienced such combat into the moment by reminding us we all share the same basic physical vehicle for navigating the world around us.

When I went searching for this quote I’d forgotten all about including Road House as an example of the tendency I’m discussing, but there you have it. The first thing Dr. Elizabeth Clay does with Dalton, after ribbing him for having gotten the shit kicked out of him over and over for years, is staple shut the gash in his side. She’s up close and personal for this, face inches away from armpit and chest hair and nipple. Often she looks up and grins at him, and if you’ve ever seen the phrase “slow smile” used in reference to a sexy person in a book and want an illustration of the concept, you’ve got one. I’m sure I don’t need to underline what the relative positioning of their heads suggests. I mean, this is a person who meets the man she will fall in love with for the first time when he’s shirtless and waiting for her to touch and heal his body. At this point she’s never seen him with a shirt. (Start as you mean to go on, I suppose.) And in the reverse, Dalton first sees the woman he’ll fall in love with when she’s approaching him to inject him with a needle and fire metal staples into his knife wound, a fate to which he stoically submits, other than that he rejects the needle and the dose of anesthesia that comes with it for reasons described in the title of this essay series.

To say that all of this supercharges their subsequent interactions with erotic intimacy is to understate the case considerably. I know people have mixed feelings about their sex scene but if you can watch their first couple of dates without wanting them to bang instantly you’re a stronger person than I am. It all begins here. So does the sexualization of Dalton’s mentor Wade Garrett, whose chemistry with the Doc is phosphorescent and who exposes his pubic hair to her in the course of revealing a scar given to him by a woman as part of their getting-to-know-you evening out as a threesome. I think there are even echoes, faint but audible, of the way Elizabeth looks at Dalton during this scene in how various men who either want to or will commit violence against Dalton look at him as well. When they finally do battle, Jimmy in particular will sexualize that violence.

Considering how resolutely un-sexy most of the bouncer-goon combat is in this film, to inject this pain-pleasure connection into the proceedings and have it pay off frequently moving forward is a minor miracle. Most action movies of the period were content with the corniest, fanserviciest, most sexist, least interesting ways of depicting sex. Road House has some thoughts in its head after all, and they’re kind of dirty.

083. Table spot

March 24, 2019DALTON: Morgan, you’re outta here.

MORGAN: …what the fuck you talking about?

DALTON: You don’t have the right temperament for the trade.

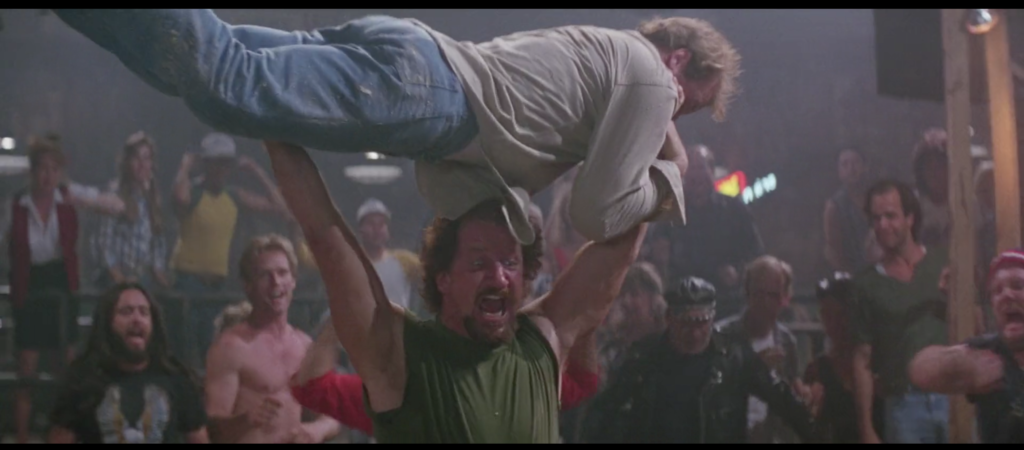

Hard to argue with that, huh? As a bouncer, Morgan does not seem to have specialized or differentiated his skill set from that which he applies to his parallel career as a Brad Wesley goon. The nominal purpose shifts from “protect the business interests of Brad Wesley” to “protect the peaceful atmosphere of the Double Deuce,” but insfoar as he simply ports the methods of the former to the latter, he’s doing far more harm than good. The table we see him shatter with another human beings body by throwing that body through that table from a height isn’t even the first table we’ve seen him fuck up in this basic way that evening, having ejected the Nipple to Nipple guy by wallopping him into a bunch of paying customers seated around one a few minutes earlier. (One of those customers was Foxworthy, so it’s hard to feel too bad about it, but still.) Not only is Morgan likely the most dangerous person in the bar to patrons of the bar, he’s also one of the most destructive to its property—and to their drink orders, at least one of which the guy above plummets through on his way to the ground. If Morgan’s job truly is to keep the peace in the Double Deuce, he really should start by bouncing himself.

That said, there is a pot/kettle element to Dalton’s callout of Morgan’s mien and methods. You’ll recall, of course, that Dalton’s first order of business upon officially assuming the position of cooler is firing Morgan during an all-hands meeting, as quoted above. But what is his first order of business upon officially assuming the position of cooler once the bar opens for business later that day? Breaking a table with a human face. Hypocrisy much?!?!?!

I doubt it. That’s not really Dalton’s style. As our examination of the Rules has made clear, apparent paradox and contradiction is virtually always a method of education via self-enlightenment. From this we can conclude that Dalton’s objection is not to breaking tables with human beings per se, but the mindset, method, and result of same. The Rules are instructive here, as they always are. “Never underestimate your opponent—expect the unexpected”? Look at Morgan’s face and tell me he’s not feeling the outrage of man who cannot believe what others have dared to do to him. “Take it outside—never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary”? Morgan is deeply inside his feelings; he has the object permanence of a furious toddler and fails to understand that no problem truly starts inside the bar, and thus can not properly assess the necessity of responding inside the bar in turn. “Be nice—until it’s time to not be nice”? I feel it’s safe to say that if you materially contributed to escalating a couple of punches thrown at Gawker by Sharing Husband into a rumble involving two dozen combatants capable of leveling the entire seating area, the time to not be nice had not yet arrived. Only the mind of a cooler knows the day and the hour. Morgan, you’re outta here.

084. Honesty

March 25, 2019Emmett is Dalton’s landlord. He rents him an apartment constructed out of the loft in his barn. It’s open to the outside and has no TV or telephone or “conditioned air,” which Emmett explains is why no one wanted to rent it from him, not even for the price of $100 a month, which he seems willing to be talked down from anyway. It is a preposterously well-designed living space to be owned and operated by Emmett. If he can afford to have it built and to rent it for a song, he probably has enough money socked away somewhere to give his neighbor Brad Wesley a run for his money in the real estate, liquor distribution, mall development, JC Penney franchising, and goonery businesses alike. But we’ll take his self-presentation as a crusty but kindly old coot at face value for the purposes of this essay, which concerns an entirely different (I think) curio about the character.

When Dalton first arrives at his ranch to inquire about the “room to rent,” Emmett’s affect is wary and his response monosyllabic. He’s a far cry from the guy who, about a minute and a half later, will kvetch about Brad Wesley to this total stranger and then tell him “callin’ me ‘sir’ is like puttin’ an elevator in an outhouse—it don’t belong.” Farther still from that affable man with his colorfully dumb similes is the Emmett we witness on the stairs up to the apartment in between.

“You honest?” he asks Dalton.

“Yessir,” Dalton responds like the good boy he is.

“You expect me to believe that?” Emmett replies. Get it? Because he asked him if he was honest, but if he doesn’t know the answer to that already he wouldn’t know if he was lying in reply, hence the follow-up inquiry, haha, how droll.

Dalton thinks it’s funny too. “No sir,” he says, smiling and laughing and warming to the old man.

Only here’s the thing: There’s no indication from Emmett’s tone of voice, facial expression, or body language that he’s kidding at all. He pretty much freezes and LOOKS DALTON DEAD IN THE EYE during the ostensible punchline part of the exchange. Without knowing anything else about Emmett, you’d think he’s dead fucking serious about wanting to know if Dalton is really being honest when he says he’s honest. He could launch into a “What do you mean I’m funny” routine right there, that’s how intense it sounds.

Then Brad Wesley buzzes his horses with a helicopter and the thaw begins. Before long we have the Emmett we’ll have for the rest of the film—a guy who drops corny jus’ folks wisecracks and aphorisms with a straight face and then immediately loosens up, letting Dalton and company in on the joke. He ribs Dalton immediately after Dalton saves him from the burning wreckage of his own firebombed house by movie’s end.

What’s going on here, then? I have a theory, and don’t I always. Emmett is a servant of the Secret Fire, Wielder of the Flame of Anor. He’s Major Briggs, he’s the Log Lady, he is of the White. Not himself a spirit, he is nonetheless their tool, their agent, sent to Jasper and instructed, Noah-like, to build a fancy schmancy loft and wait for the indwelling. To him shall come a stranger, one who will make the wrong things right. How will I know him, Emmett asks the glowing voice, and that voice replies You will test him with paradox, the language of the righteous. Then and only then will you recognize him as a traveler on the Dalton Path.

You honest/you expect me to believe that. Be nice/until it’s time to not be nice. Yin/yang. The White Lodge and the Black.

085. The Baseball Player

March 26, 2019On a warm summer’s eve

In a bar down in Jasper

I saw “The Baseball Player”

Ersatz vintage, prob’ly cheap

Frank Tilghman was a-starin’

Out the window at the rumble

When Morgan overdid it

Then he began to speak

He said, “Son, I’ve made a life

Out of hurtin’ people’s livers

Knowin’ not to card ’em

By the way they held their eyes

And I heard that you’ll be stayin’

Out with Emmett by the river

Have a taste of my whiskey

And give me some advice”

So he handed me a bottle

And he ogled as I swallowed

Then I smoked a cigarette

And glistened in the light

And the night got deathly quiet

And his face made weird expressions

I said, “If I’m gonna be your cooler

I’m gonna be your cooler right

You’ve got to know when to hold it

Know your opponent

Know when it’s time for nice

And know when it’s not

You’re gonna pay me money

To drive a man’s face through a table

Cuz it’s my way or the highway

I’m extremely hot

Every cooler knows

That the secret to survivin’

Is knowin’ which guy’s throats to rip

And knowin’ who to kick

‘Cause no one is a winner

And every fight’s a loser

Go ahead and call me dickless

But I sure won’t show my dick”

And when I finished speakin’

I turned back toward the window

Crushed out my cigarette

And wandered to my Benz

And somewhere in his office

Frank Tilghman stood there grinnin’

Then doctored dirty words

In the graffiti in the Men’s

You’ve got to know when to hold it

Know your opponent

Know when it’s time for nice

And know when it’s not

You’re gonna pay me money

To drive a man’s face through a table

Cuz it’s my way or the highway

I’m extremely hot

You’ve got to know when to hold it (when to hold it)

Know your opponent (your opponent)

Know when it’s time for nice

And know when it’s not

You’re gonna pay me money

To drive a man’s face through a table

Cuz it’s my way or the highway

I’m extremely hot

You’ve got to know when to hold it

Know your opponent

Know when it’s time for nice

And know when it’s not

You’re gonna pay me money

To drive a man’s face through a table

Cuz it’s my way or the highway

I’m extremely hot

086. The Sex Scene from Road House Is Hot (A Note from the Author)

March 27, 2019The sex scene from Road House is hot. I think so. Presumably at least some of the cast and crew who made Road House think so. Most importantly, the people think so. It was a squeaker, but “The sex scene in Road House is hot” beat “The sex scene in Road House is not hot” 51% to 49% in a poll I threw up on my twitter feed late some night. That’s a presidential election margin, but without the racist electoral college to fuck it up, so much like the participants in the sex scene in Road House, the motion stands.

We’re not going to be talking about the sex scene from Road House just yet, mind you. That’s sometime off in the distance. If you were wondering, I think of rolling out these essays like one of those super slowed-down remixes, the ones that make Justin Bieber sound like Oneohtrix Point Never, or the score for a vaguely arty science fiction movie that gets great critical notices and does dece numbers at the box office because Emma Stone is in it or something. It’s like building the movie with stop-motion animation, one essay at a time. Much unlike the participants in the sex scene in Road House, I’m taking my time.

But I wanted to get this out there as groundwork. I wanted to prep you for what’s to… *LOWERS SHADES TO LOOK YOU DEAD IN THE EYE* …come. As a practical matter I want to give those of you who feel strongly in the other direction a chance to take the train. It’s my way or the highway. What I say? Goes. I say that the sex scene from Road House is hot. And that’s all you need to know, son.

087. Jack

March 28, 2019As we near the century mark here at Pain Don’t Hurt, faithful readers will not be surprised to hear me sing the praises of Jack once again. It’s my growing conviction that Road House may be viewed as the origin story of the heir to the cooler’s mantle possessed by Wade Garrett and passed on to Dalton, and that heir is the man above. Why? Because in less than a second after that image, he is also the man below.

Jack goes 0 to 100 real quick.

As well he should! Here, he is reacting to Sharing Husband’s punch and shove of Gawker into Morgan and the entire crowded bar full of patrons. Jack knows the Double Deuce generally and Morgan specifically well enough to know that all hell is about to break loose, and he knows his own trade well enough to know it’s on him to stem the blood-drenched tide. He does so with sufficient alacrity to send the stool on which he’d been sitting skittering halfway down the hall behind him. The dude’s like the Flash, for real. He’s even wearing red. This is the first time we see him spring into action, but as we’ve learned, it is not the last.

The bouncers of the Double Deuce are not a promising lot when Dalton first arrives to take charge of them. Hank is too timid. Steve is too horny. Morgan should by rights be not the bouncer but the bounced. Younger is…present. Jack, though? In A Song of Ice and Fire he would be referred to as the true steel, supple as needed, able to be honed, unbreakable when it matters. Jesus Christ would recognize him as the good ground, bringing forth fruit an hundredfold. It is toward that good ground that the Way of Wade Garrett and the Dalton Path lead. Beyond? The undiscovered country.

088. Hobbyhorse

March 29, 2019Few of Road House‘s many would-be idioms and aphorisms are afforded as grand a debut as, arguably, the dumbest of them all. You can thank Red West, the actor who plays Red Webster (you can’t spell “Red Webster” without “R-E-D-W-E-S-T”), for that. The man sells every line of down-home wisdom and ain’t-that-a-kick-in-the-head fatalism like Pete Stroudenmire sells roomy family-friendly vehicles during Wagon Days. You can of course also thank Rowdy Herrington, the film’s director, and John F. Link and Frank J. Urioste, the film’s editors, who grind everything to a halt so Red can deliver it almost right into the camera before a hard cut to the topless bar where we first meet Wade Garrett. The line all but takes off its own top and dances around on stage in a g-string, that’s how much attention it gets.

Ah, what line, you ask, and I’m glad you did.

Picture it: Jasper, Missouri, 1989. A young cooler, new in town, visits the small business owned by Red Webster, uncle of the most beautiful woman he’s ever seen. Red keeps a black and white glamour shot of his niece on the wall of his workplace, piercing the young cooler’s heart, and raising more questions than it answers. On the way into the store the cooler passes by two extremely handsome goons, who stare at him and smile, like crocodiles eyeing a wildebeest at the watering hole, or like Brad Wesley looking at literally anything at any point in the whole movie. The cooler discovers that the store has been ransacked. Frightened, he turns to the uncle of the woman he loves and says…

DALTON: What happened? Did you get robbed?

RED: Every week.

Dalton pauses to contemplate the sultry black and white photo of Red’s niece hanging on the wall next to his business license, the two cornerstones of any successful enterprise.

DALTON: So what does he take?

RED: Who?

DALTON: Brad Wesley.

RED: Ten percent—to start. Oh it’s it’s all legal-like. He formed “The Jasper Improvement Society.” All the businesses in town belong to it.

DALTON: Everybody pay?

RED: [LOWERS SHADES TO LOOK YOU DEAD IN THE EYE] Does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick?

Oh it’s all aphorism-like. “Does a bear shit in the woods?” “Is the Pope Catholic?” This is supposed to be a question like that, one that all but answers itself in the affirmative and in so doing illustrates how obvious the answer was to begin with. But, and perhaps you’ve already seen the issue here, there’s one important difference between those sayings and this one.

Does a bear shit in the woods? Yes, that’s where bears shit.

Is the Pope Catholic? Yes, the Holy Father is a member in good standing of the Roman Catholic Church.

Does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick?

No. [pause for laughter] No!

The answer to “Does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick?” is supposed to be “yes,” clearly. But no, a hobbyhorse does not have a wooden dick. I’m not sure why it would?

Nevertheless the line is uttered with such total conviction that I’ve found myself second-guessing the answer. Does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick? Is there a black market for anatomically correct hobbyhorses of which I am unaware? Do they make the rounds on the auto-supply circuit, as gag gifts perhaps, or as a little something special out back saved for only the best customers? What does Red Webster know that I don’t? A lot, I assume. A whole lot.

089. Whisper

March 30, 2019By this point in the evening the word has begun to spread. Dalton has told Carrie Ann, and she’s made a huge fuss, at least partially within Pat McGurn’s earshot. She’s since gone on to report it to Hank, like a little girl telling her brother on Christmas morning that Santa came. Hank is about to tell Steve the story of the throat-ripping incident, and Steve will pronounce it “bull shit.” For now, Pat must report the news to his partner in Brad Wesley Enterprises, Morgan. He does it in low tones, as befits a bearer of ill news:

“That guy at the end of the bar is fuckin’ Dalton, man.”

Pat’s whisper is as the footsteps of doom: He’s just introduced Morgan to the man who will murder them both, so that Red’s Auto Parts and Stroudenmire Ford might live anew.

But it’s not foreknowledge of their fate that has knit lines of worry across Pat’s brow, or rendered Morgan’s strangely adorable face a soft Winnie-the-Pooh mask of concern. Dalton’s reputation precedes him. Like nearly all of the Double Deuce’s barfolk, they’ve heard the legends; even the slackasses and shitkickers on Frank Tilghman’s payroll would have a hard time looking themselves in the mirror (okay, maybe not Steve) if they had not kept abreast enough with the trade to be aware of the second most famous bouncer in these United States. If your role at an establishment that has hired Dalton is to practice throwing human beings through furniture (as is Morgan’s) or draw a bartender’s paycheck at your uncle’s insistence while stealing, in 2019 dollars, over $300 a night (as is Pat’s), this is bad news indeed.

Pat, at least, has the good sense to brown up a bit, calling Dalton “buddy” and asking his name, though he already knows it, and though Dalton only says “coffee, black” in response because he’s a bit of a prick, at least before he’s officially being paid not to be. Morgan, you’ll recall, barely manages to titter his way through an icebreaker involving the size of Dalton’s balls, which is saying the quiet part loud if you ask me.

These guys are desperate to be noticed, and desperate to not be noticed. They want to make themselves seem too pliant or too tough to actually be crooked, and hope Dalton doesn’t look any closer. Which is to say they may know who Dalton is, but they have no idea who Dalton is. This is the (second) best damn cooler in the business, you fools. You’re already dead.

090. “That guy in the corner’s fuckin’ Dalton, man.”

March 31, 2019[Chorus: Pat McGurn and Morgan]

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

He’s firing somebody real, fired by fuckin’ Dalton

Send your goons to the bar, maybe he’ll assault them

[Verse 1: Tilghman]

Hold up, Jasper simmer down

Hiring the best, bitch, now he’s here in town

Flew to New York, saw him shirtless, lookin’ fine

Ooh, baby check him out, you’ll go Jeffrey Healey blind

(Uhh)

Hey Pat, black coffee

Serve this motherfucker cuz he drinks for free

Tell these motherfuckers who they think they see

Put his feet through your teeth then he’ll break your knee

Cuz he’s the cooler, the cooler cooler, like he’s your ruler

Teaching rules too, he’s gonna school you, don’t suffer fools too

He should carpool, like many fools do he searched for faith down at NYU

Hospitalize you, that’s what he will do

Here’s my money, gonna give you six figures, man

I thought you would be bigger, man

Wesley’s fuckin’ parties make too much fuckin’ noise

Break into Brad’s house, kill his fuckin’ boys

Beast

[Chorus: Pat McGurn and Morgan]

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

He’s firing somebody real, fired by fuckin’ Dalton

Send your goons to the bar, maybe he’ll assault them

[Verse 2: Morgan]

Ooh, I know you love it when I bounce a guy

Make you think about all of the incidents I trounced a guy

Go into the bathroom and ask Judy for an ounce to buy

Think I’ll tell him “You’re a dead man,” mispronounce a guy

Oh word? Ain’t heard of Wesley? He’ll denounce this guy

Beating up O’Connor, make him bleed some fluid ounces guy

Carrie Ann announced this guy, see his mullet flounces guy

Then ju—okay, I got it

Then just watch Jimmy as he pounds this guy

It will get awkward when we watch as Jimmy mounts this guy

I heard that his testes were sufficient for a dump truck

Then he said “Opinions vary” and I felt like such a dumbfuck

Gonna call Wade Garrett “Dad,” comparatively I’m a young buck

Then I’m gonna die offscreen while wearing moonboots, just my dumb luck

Yes, Lord, but for now I’m fit and able

Gonna pick some guy up, throw him through a table

I’m beast

[Chorus: Pat McGurn and Morgan]

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

He’s firing somebody real, fired by fuckin’ Dalton

Send your goons to the bar, maybe he’ll assault them

[Verse 3: Pat McGurn]

Uhh

I’m Pat, this the finale

A big truck at the Wagon Days rally

I’m behind the bar, taking money from the tally now

Told me take the train and told me not to dilly-dally

Mmm

Uncle Brad on the line, mad on the line

He’s opening two Dillard’s at the same damn time

Frank’s eyeing me like he still wants to have sex

Girl, I am John Doe from X

Girl, I’m Patrick McGurn

AKA Brad looks at me with concern

He gives me money that I do not earn

Lists me as a dependent on his tax return

Mmm

Kill ’em all, dead bodies in the hallway

Dalton’s involved, and my chest got in his knife’s way

Mustache thin, Morgan thicker

Sister-son, chickendicker

Beast

[Chorus: Pat McGurn and Morgan]

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

I heard Frank Tilghman hired fuckin’ Dalton

And yeah we’re fuckin’ fucked, that guy is fuckin’ Dalton

He’s firing somebody real, fired by fuckin’ Dalton

Send your goons to the bar, maybe he’ll assault them

091. Hillbilly elegy

April 1, 2019092. “Fuck ’em, they’re brothers.”

April 2, 2019Sibling rivalry. Toys, games, grades, sports, popularity, attention, romantic success, money, status, a parent’s love: There are plenty of reasons to fight with your brothers and sisters, and they evolve over time just like you do. It’s hard to imagine now, as a father and stepfather myself, but time was me and my brother would go at it hard, physically, rumbling around in our basement after some dispute or other. Someone would want to play with something the other one had, or was using, or wasn’t using, or some dumb nonsense. I didn’t like how he’d make fun of me sometimes, and I assume the feeling was mutual. We made up mean nicknames for each other. We’d get each other in headlocks and someone would cry and our mom would tell us to knock it off. During any kind of tussle with my siblings—we have a sister too and if she’d join in with my brother I’d like physically back her away by putting my head against hers, which I did to my brother all the time too, like I was moving them with my mind—I’d kind of stick my tongue out of my mouth and bite down on it in determination, which they referred to mockingly as “tongue power!”, which I absolutely hated. It’s wild, that we fought, partially because I’d flip the fuck out if my kids started laying hands on one another, and partially because we always got along. When I think back on my relationships with my siblings (I am the oldest of three) I can’t think of a single time any of us argued or fought about anything in any serious way. The physical spats had no meaning. I think in my last fight with my brother he bloodied my nose, and after that we both realized without saying so that physically fighting each other was a bad idea.

Family relationships take very sharp turns sometimes. Certainly ours has, both within our original unit and in our own lives with our own families. Time and circumstance have shown me, though I didn’t consciously realize it at the time, that I would I would die without hesitation for these people whom I love so much, without any hesitation at all. I’d imagine they’d say the same if I asked them, which I won’t. I’d rather them never need to know.

Anyway, here are two grown men in denim, throwing haymakers and decking each other onto and off of a pool table in the middle of a crowded bar. Who knows why. Who knows why anyone in the Double Deuce during its Mos Eisley Cantina phase does absolutely anything, or why they choose to do it there of all places. “Fuck ’em,” says Horny Steve the bouncer when Hank interrupts his crude attempt to pick up a teenager to point out the altercation. “They’re brothers.” Once they were children who played together, like my brother and I did. Maybe they fought occasionally like we did. Maybe they spent the preponderance of their time, like the vast overwhelming majority of it, playing whatever the period-appropriate equivalent of He-Man and G.I. Joe was, or watching Star Wars or wrestling or The Goonies or Clue, like my brother and I did. And then they grew up and assaulted each other in the worst bar in Missouri. I know roads like that exist for people. I never ever want to go down one.

093. When Tinker Attacks

April 3, 2019This, as you know, is Tinker. Broadly speaking he is the comic relief in Brad Wesley’s brute squad, which if you’re familiar with people like Pat McGurn and O’Connor is really saying something. He lurks in the margins of Dalton’s first visit to the Double Deuce, making time with some lady while sitting next to where Morgan’s posted up at the bar. We get our first good look at him approximately five seconds before the Bleeder reads him to filth, to the point where it would probably be better for him if he hadn’t show up at all. His goonsmanship after this scene is largely undistinguished; like most Wesleyans he exists primarily to get his ass kicked, but unlike, say, Jimmy or Ketchum or Morgan you never see him wreck shop in any way. He is the sole survivor among the goons, that’s how little Dalton considers him to be a threat. He gets knocked out of the final fight when Dalton dumps a stuffed polar bear on top of him, during which maneuver Tinker carries on like he thinks the bear has come to life and is about to maul him, like Tuunbaq has come to Jasper to exact further revenge against the colonizers. He is even granted a sort of clemency by the cabal of old men who show up to save Dalton’s ass by Sonny Corleone-ing Brad Wesley: Instead of killing him too, they ask him to participate in the cover-up, which in his own moronic way he does.

But look at this shit up above. Look at it! We’re in Tilghman’s office, where Tinker and O’Connor are muscling him into rehiring Pat. At this particular moment, Dalton is tussling with O’Connor after having broken Pat’s nose and roundhouse-kicked him through a plate-glass window. What did Pat do to occasion this treatment? Whip out a gigantic knife with no provocation and attempt to murder Dalton with it. Having observed all this firsthand, what does Tinker do? You guessed it!

Things wind up going for Tinker much the same as they did for Pat. Dalton kicks him with both feet, forcefully enough to push himself and O’Connor through the shattered window as well. Tinker gets knocked onto the couch, where the other bouncers find him and proceed to immobilize and pummel him. Like one of them holds his arms and the other punches him in the gut. It’s heel tag-team shit, but frankly he deserves it.

Why? Because as we’ve mentioned before, here’s the thing about Tinker: He comes closer to actually killing Dalton than anyone does until the climax of the movie. That knife he whips out and holds aloft like Anduril, Flame of the West? He slashes Dalton in the side with it while Dalton’s in the middle of fending off O’Connor, and if Dalton’s turn toward his new oncoming attacker had been timed just slightly differently his intestines would be hanging out. Dr. Elizabeth Clay would be calling his time of death, not asking what particular philosophical discipline he studied at NYU.

Maybe there’s a lesson in this for us, if we care to look for it. We are all occasionally much better at being ourselves than is our standard. Tinker is, for this brief moment, very good at his job of being a goon—too good, almost, insofar as he came within a hair’s breadth of murdering a man in front of about a hundred witnesses, but good regardless. Most other moments I wouldn’t hire Tinker to whack a piñata, much less the (second) best damn cooler in the business. There’s a Tinker in all of us—a killing machine and a stammering goofus bested by taxidermy. Sometimes you eat the bar, and sometimes the bar, well, he eats you.

094. Trustees of modern chemistry

April 4, 2019“Bad element over there,” says Brad Wesley of the Double Deuce when he and Dalton first meet. Brad Wesley should know, of course, because Brad Wesley has several of the protons and electrons comprising that bad element on his payroll. That’s the way we tend to think of the Double Deuce’s lowlife patrons, the people Frank Tilghman hired Dalton to clear out. Pat McGurn and Morgan, members in good standing of Wesley’s goon squad, in Pat’s case a thief and in Morgan’s case a rageaholic sadist. Stella, the coke-dealer waitress, and Steve, the bouncer who likes the bar’s patrons and his sexual partners the way Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen like giant gorillas named Mighty Joe: young. Sharing Husband and Well-Endowed Wife, who’ve decided to turn the Double Deuce into a theater for their loveplay. Gawker, who ain’t got twenty bucks. Foxworthy, who sexually harasses Carrie Ann. Nipple to Nipple Guy, who sexually harasses Denise. Men who throw bottles at the faces of blind guitar players when they announce they’re taking a break from the set to use the bathroom. A Knife Nerd in a Hawaiian shirt. Mr. Clean. The Fuckemtheyre Brothers. Tinker. You get the picture.

But look at these two lost souls. No, not Younger and Jack, though I can’t imagine they’re feeling like they’ve found their calling at this particular moment in time. The woman in the upper left is seated alone at a relatively isolated table, where she is having an agitated conversation with no one. She’s screwed up her face angrily, and makes the occasional wild gesticulation. Is she drunk? Yes, probably. Is she also severely mentally ill? Almost certainly. She’s one of Dalton’s infamous “trustees of modern chemistry” insofar as the chemistry in question is lithium.

And that old man passed out on the floor? He’s the one person we see Frank Tilghman involve himself personally in ejecting from the bar, when he orders Younger to give the guy the heave-ho. He’s not propositioning women with his hands, or stabbing anyone, or throwing anyone through a table. He’s an elderly alcoholic who, if he doesn’t sleep there, is going to sleep on the street. “Get him outta here,” Tilghman says. Tilghman, who employs Pat and Morgan and Stella and Steve and has a bar full of the worst motherfuckers on the planet, is effectively installing one of those benches rich areas of big cities use where there’s curves or bars or jagged spikes at regular intervals to prevent any homeless people from getting too comfortable.

What we’re seeing here is the Reagan/Bush-era destruction of the social safety net in microcosm. With mental institutions shuttered due to lack of funds, people wind up out on their own with no one and nothing to help them. Some wind up in the Double Deuce, waving off imaginary interlocutors underneath Tilghman’s office window, or passed out on the steps along the way. Later on in the film Dalton will spare a similar old man—the same old man, quite possibly, though it will require further review—the fate of expulsion from a diner whose owner is pissed that he’s nodding off at the counter. But no such luck here. No one takes this woman or this man and powerbombs them through a table, but they’ve fallen through the cracks nonetheless.

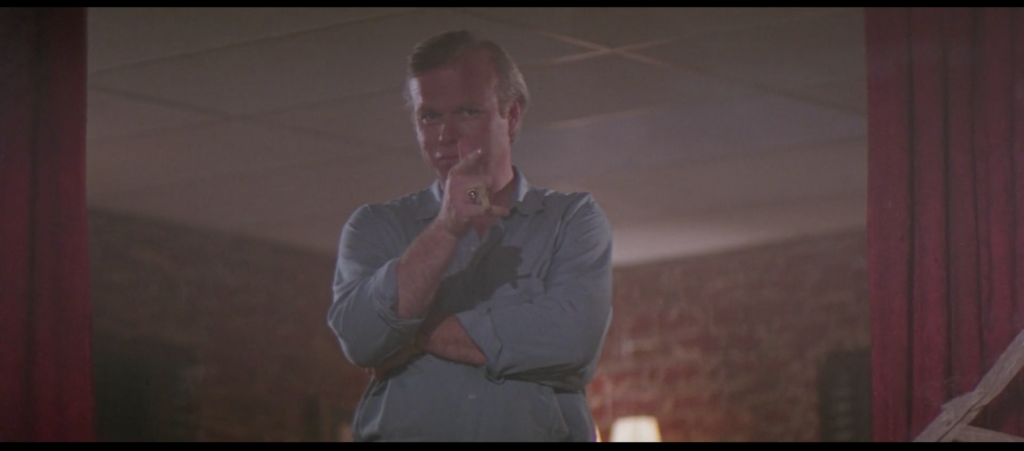

095. Tilghman’s Affect

April 5, 2019Frank Tilghman has affect issues. That’s one way to describe it, and probably a mild way. At virtually no point during the entirety of Road House does the demeanor selected by actor Kevin Tighe track with the reality of his character’s surroundings. It’s why he spends the opening sequence grinning like the Joker even though from a narrative standpoint he’s more like Commissioner Gordon. It’s why he reacts to firing his piece-of-shit bartender (my own headcanon notwithstanding) like he’s getting divorced. And it’s why, when the Double Deuce is in the throes of a full-scale riot launched when a husband with a cuckold fetish decks a dude for refusing to pay to kiss his wife’s tits and his own bouncer goes berserk in response, he signals to Dalton with a smile and a “hey hotshot, come on up and see me sometime” finger point gesture. At that very moment he can see every piece of furniture in his seating area getting smashed into splinters, he can see human beings flying over the bar and into the bottles and glasses behind it, he’s watching people commit felony assault and attempted murder, he’s seeing people incur injuries that will potentially last a lifetime, and his face and body are doing the equivalent of that “chk-chk” sound you make when you wink at someone. It’s possible he’s the weirdest man in Jasper. It’s possible he has less concern for the lives of others than Brad Wesley. The greatest trick the devil ever pulled…

096. Estimate

April 6, 2019“Well, Mr. Dalton, you may add nine staples to your dossier of 31 broken bones, two bullet wounds, nine puncture wounds, and four stainless steel screws. That’s an estimate, of course.”

Is it, Doc? Is it really? Because it sounds to me like you’re at first reading, then reciting from memory, actual statistics from the medical file that Dalton carries around with him. (“Saves time.”) Thirty-one broken bones, two bullet wounds, nine puncture wounds, and four stainless steel screws—that’s pretty specific. Not a lot of guesswork involved, I shouldn’t think. Unless you mean the nine staples you’re about to administer may wind up being ten staples, or eight stapes, and you can’t tell until you start. Or unless previous doctors whose notes are contained in that file threw up their hands and were like “I dunno man, this guy’s fucked up what can I say,” and that this is recorded in the file somewhere, perhaps in the place where it says what college he graduated from, which is admittedly a thing that it says and thus an indicator that this is a potentially very unorthodox medical file.

But if none of this applies, the smart money is on “the writers wanted Doc to say something that sounded smart, like ‘that’s an estimate of course.'” It isn’t smart at all of course. But I’ll say this for Kelly Lynch: She makes rattling off a bunch of specific injuries and then saying “just blue-skying it here” come across like you’re in the presence of a Dead Ringers–level eccentric medical genius. That would explain some of her wardrobe choices, and her taste in men. That’s an estimate of course.

097. “Anyway, I’ve come into a little bit of money.”

April 7, 2019Frank Tilghman has just met Dalton for the first time, after what one assume is years of hearing tell of his exploits from other barfolk. He explains he runs a little nightclub called the Double Deuce just outside of St. Louis. It used to be a sweet deal, he says. Now it’s the kind of place where they sweep up the eyeballs after closing, he laments. His face falls, ashen. He looks out over the bustling crowd at the Bandstand, the club where Dalton currently works, but it’s as if he doesn’t see it at all. Then he turns back toward Dalton and, with the most normal facial expression imaginable, he says “Anyway, I’ve come into a little bit of money.”

Oh, is that a fact?

In the past, when fleshing out the romantic backstory between Tilghman and Pat McGurn, I’ve theorized that one of Tilghman’s ex-wives’ doting mother left him a small fortune, having turned out to be much fonder of her daughter’s former husband than the daughter ever was. Perfectly harmless. I’ve also speculated that he was involved in one of those “seduce an old lady, get written into her will, and dump her overboard during a cruise” schemes, like Not Great Bob’s boyfriend did (allegedly) in Mad Men. You have to admit it’s possible.

But look at that grin again. Look at that rictus of arrogance and cruelty. This is the face he’s choosing to display to a man he’s going to spend top dollar on, a man who will turn the struggling Double Deuce into the hottest nightspot in a hundred miles, a man who will run the bad element out of the bar, a man who will almost singlehandedly destroy the organized crime ring run by the richest man in Jasper. Until he dies, that is, slain in the course of the battle with Dalton.

Slain by Tilghman.

The new richest man in Jasper.

You know the 7-Eleven, the Fotomat, the mall, christ, the JC Penney? Brad Wesley brought them to town, he says, and no one contradicts him. But if I were Dalton, I’d spend some of my mid-six-figure yearly salary on a forensic accountant. Shell corporations within shell corporations within shell corporations are involved, I’d imagine. And what address is listed for those corporations, in the end? Whose name is on the dotted line?

Cui bono?

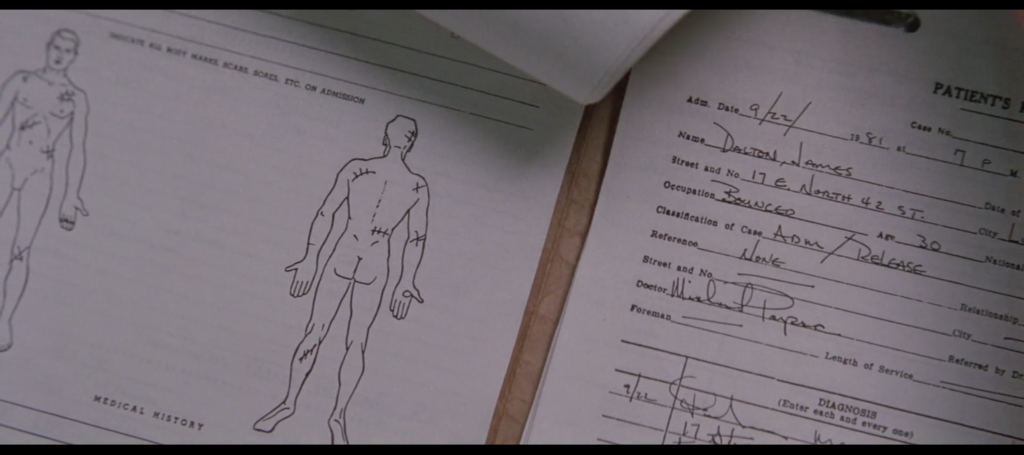

098. James

April 8, 2019Dalton’s first name is James. There it is, in black and white, in his medical file, next to a drawing of his bare ass. (Not technically true, but you have to admit the resemblance is remarkable.) I forget this, frequently. I forgot it for the entirety of this project, until I happened across this frame while searching for something else in this scene, the one where he meets the Doc. Nothing’s gained by knowing Dalton is more than a mononym. For one thing, it costs him a certain air of humility. Jack, Hank, Younger, Ketcham, Karpis, Stella, Judy, the Uncredited Bartender—half the cast is not afforded the dignity of a name uttered onscreen. Why should Dalton be any different? Because he’s the cooler? That presupposes that, like Superman, he is like them but he is not one of them. That’s not a presupposition I’m willing to make. The Dalton Path is a path of humility, and you must trade in your Mercedes for a hooptie in order to travel it. I wonder if Dalton eschews the use of his first name, to the point where no one, not even his lovers and closest oldest friends, even use it, in order to annihilate the self in this way—like a maester dropping his house name, like a nun adopting the name of a saint, like Jack Napier calling himself Joker to represent his broader brighter outlook on life. Maybe that’s why my brain purges itself of this knowledge regularly, and then purges itself of the knowledge of the purging. It’s not like I could tell you when I learned Dalton’s name, but I know that I did, and I know I forgot it, and I know that I’m remembering it rather than discovering it for the first time, and I couldn’t tell you when any of those events originally took place. There’s a bit in Batman: Year One, by Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli, where the young Batman must dive off a bridge to save the infant of the young James Gordon. In the process he removes his mask, or his mask is removed, or he was dressed as Bruce Wayne all along and had to blow cover to make the save, which was to him more important than preserving his secret identity. Gordon gratefully accepts his still-living child from this strange man, then graciously lies that he’s misplaced his glasses in the confusion, and couldn’t recognize a face glimpsed without them if he tried. I’m sorry; what were we talking about?