We joke here at Pain Don’t Hurt. We do. And we laugh, don’t we? We laugh, and we kid. We kid the movie. But I have not decided to spend three hundred sixty-five days of my life—a significant fraction of my life no matter how long I live, a fraction my kids can mention at my funeral for some chuckles—to write about a film I find funny on account of it’s impossible to recognize myself in it. On the contrary. As I’ve said in the past, Road House endears itself to me. Dalton endears itself to me. Patrick Swayze endears himself to me. I like these people, and I like the way they enact…I dunno, the things that people care about. They like to drink and dance and sing and fuck. They have to navigate moving to a new town, meeting new people, taking a new job. They keep in touch with friends. They try to fight against assholes who are ruining it for everyone. Does it matter that they get paid six-figure salaries to toss professional wrestlers out of a bar with a dirt parking lot? Only insofar as that makes it funny. There has to be something underneath to be made funny if the thing’s worth writing about it all.

This is my seventh consecutive day writing about a phone call between Dalton and Wade Garrett that lasts for one minute, to the second depending on what you count as the start or finish. It’s a funny conversation because Sam Elliott pronounces things in an unusual way, because there’s a continuity error I can spin into a CLUE, because at times it seems to undermine the system of bar-fame upon which the rest of the movie depends, because Wade calls Dalton mijo and thus invites an entire range of gutter-minded speculation.

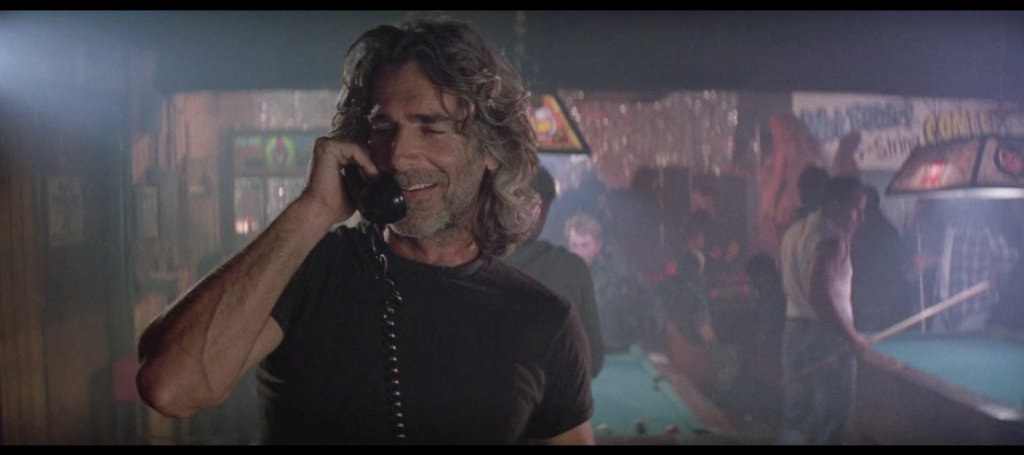

But as Wade’s mile-wide grin when he hears who’s on the phone shows us, these men are friends, and their friendship is, I think, why I’ve gotten stuck on this single minute of film for an entire week. The friendship is what makes it a rich text, not just something you can say a lot of silly shit about. It’s the reason I like it, because it makes me like the men involved.

Wade, for instance. Wade characterizes his current place of work as such a haven for drooling cretins that “This place has a sign over the urinal that says ‘Don’t Eat the Big White Mint.'” Yet earlier—less than a minute earlier, since the whole conversation is over and done in sixty seconds—he tells Dalton that he’s in hog heaven, that “If I was doin’ any better I couldn’t live with myself.” His smile hear shows that he means it: He is thrilled to be working in a place this skeevy and dumb, where the troops charge the stage with water guns and the topless dancers flash him looks of gratitude and attraction along with everything else they flash. He doesn’t need to explain away the apparent contradiction to Dalton, his pal and confidant. He knows the kid’ll understand.

Dalton, then. Dalton seems more at home during his conversation with Wade than at any other point in the film so far other than his chat with Cody, and for the same reason: He’s not trying to impress or intimidate Wade, because Wade is his friend. Moreover, he’s not exhausted, or wounded, or trying to kick someone’s ass. His affect is genial, maybe ever so slightly deferential, the way you sound when you’re talking to a friend you haven’t seen in a while, and you’re just grateful to bask in their presence, so grateful you feel you owe them just the tiniest amount of subordination to whatever would make them happy in the moment. When Wade asks if he’s in any kind of trouble, Dalton tells him it’s nothing he’s not used to; as he does so he kind of tosses his hand up and then down in a hurry, a nervous “aw it’s nothin'” gesture that’s extraordinarily adorable. So is the uncontrollable tinge of chuckle that bubbles up as he says “But it’s amazing what you can used to, isn’t it?” He’s tickled by this, and tickled by his ability to express that feeling, and—again—confident that his friend won’t need this explained, that he’ll just get it. Indeed this occasions the “don’t eat the big white mint” gag, at which Dalton laughs gladly. Just a few seconds earlier he was nervously bringing up the Brad Wesley situation; he’s now able to very sincerely laugh at a very dumb joke simply because Wade’s the one who told it to him.

That Sam Elliott is good in this scene is obvious. He’s playing a sexy funny rough-and-tumble super-bouncer, he sounds like Sam Elliott, he nails it. That Patrick Swayze is good in this scene is crucial. It’s one I’d point people to in order to explain why he and Dalton are so appealing in this picture. There’s an ease to what he does here, a feeling like somewhere out in the multiverse there exists a Patrick Swayze who looks and acts and behaves in this exact way, and they simply traded places for a bit so they could make this movie. “What does this action hero sound like when he calls up one of his buddies” is not a question that gets asked very often, much less answered, much less answered with such charm, and since it’s Patrick Swayze we’re looking at, such beauty.

You leave this phonecall thinking Wade Garrett’s someone you wanna hear some stories from. You leave thinking Dalton’s a guy it’d be fun to grab a beer and shoot the shit with, maybe get a little philosophical in (“It’s amazing what you can get used to”) in the process. You leave thinking these guys are friends. They’re my friends too.

Tags: dalton, road house, the phonecall, wade garrett