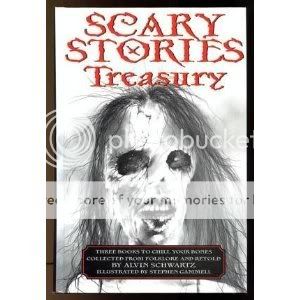

Scary Stories Treasury

Alvin Schwartz, writer

Stephen Gammell, artist

HarperCollins, 1995

115 pages, hardcover

$9.95

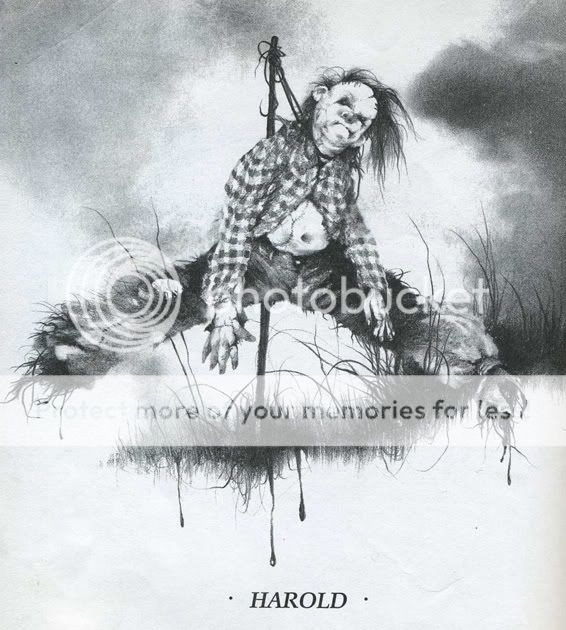

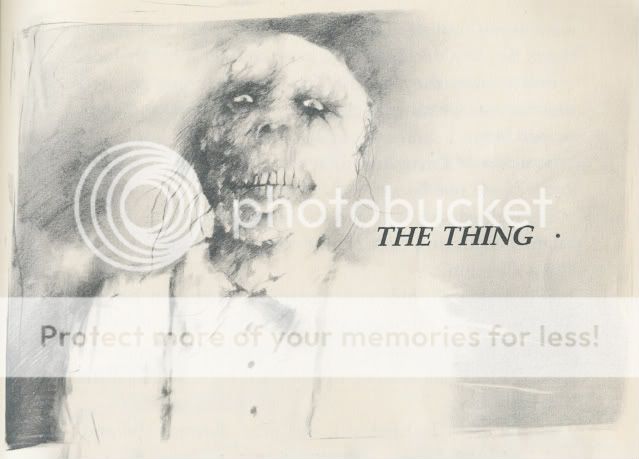

It was a red-letter day when I snagged this omnibus edition of the three collections of scary stories from folklore assembled and retold by Alvin Schwartz and illustrated by Stephen Gammell: 1981’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, 1984’s More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, and 1991’s Scary Stories 3: More Tales to Chill Your Bones. Honestly, I could skip this review and just post the collection of Gammell’s world-beating brain-searing images I gathered up from the Internet, and any point I’d have tried to make would probably be made at least as effectively. If you ever came across these books as a kid, you probably, and this is no joke, remember some of these illustrations better than the faces of your best friends. Like a proto-Al Columbia, veteran illustrator and Caldecott Medal winner Gammell found a way to depict a kind of evil that seems to have seeped into and corrupted those depictions themselves. Instead of deconstructing these images like Columbia does–using sketches, abandoned work, damaged or destroyed pages and so on to suggest that these things almost too horrible to truly commit to paper–Gammell uses washed-out black and gray inks to suggest forms slowly coalescing into being from…someplace else, someplace we can’t fully see and wouldn’t want to. On the memorable occasions when he comes right out and draws these things where you can’t help but look at them, and seemingly they at you, it can quite literally be difficult to sustain that gaze. I defy you to stare at this image, for example–astutely chosen as this omnibus collection’s cover; no effing around here!–without eventually just shaking your head and saying “Jesus.”

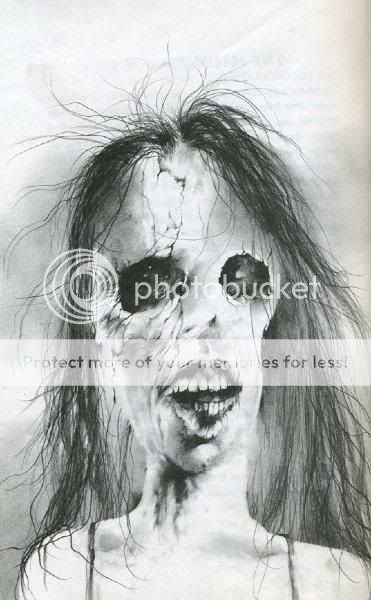

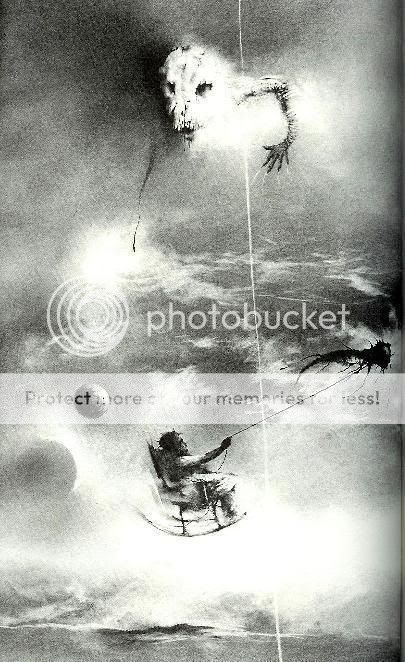

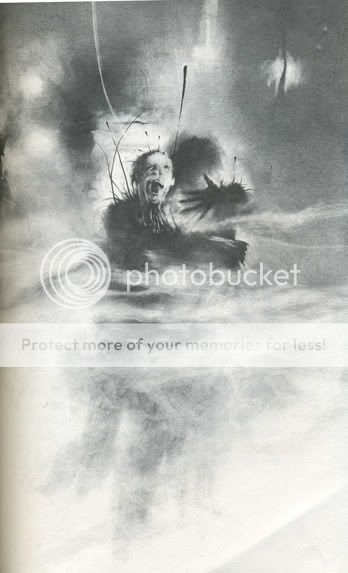

But Gammell is equally adept, and just as haunting, when he’s not depicting anything in particular. In a few memorable pieces–sometimes in illustrations for the front matter, sometimes for the stories themselves–he goes full-on black-psychedelic, creating images that suggest surrealism but which replace the traditional visual punning of that movement with disconcertingly decontextualized tendrils and splatters and parts of leering, screaming faces. My favorite of these is the below illustration, for the story “Oh, Susannah!”

Which leads me to the storyteller, Alvin Schwartz. A folklorist with dozens of collections under his belt, Schwartz displays here what I imagine to be a hugely underrated and underremembered proficiency with his prose. These are books for children and young adults, but Schwartz uses that to his advantage. In his best moments, he takes the economical prose typically used to communicate to these age groups–that “So-and-so was a person and this is what happened to him” factuality–and employs it to tell stories of not just the unexplained, but the unexplainable. Again, “Oh, Susannah!” is my favorite. A college student names Susannah comes home late at night and tries to go to sleep, only to be awoken by her roommate, already in bed, singing the old Stephen Foster song. When she switches on the light to confront the roommate, she discovers that the roommate’s head is missing. The story ends with Susannah telling herself “I’m having a nightmare. When I wake up, everything will be all right….” Who murdered the roommate? How long ago did it happen? If the roommate is dead, who was singing the song? Is Susannah having a nightmare? Will everything be all right? What does any of this have to do with the cosmic hellscape with which Gammell has adorned this story? We don’t know, and Schwartz’s all-business prose offers us no comforting room for interpretation. It is what it is, and what it is is horrifying.

Schwartz’s technique can make even the collections’ most familiar stories freshly disturbing. Consider his take on the old “the call is coming from inside the house” urban legend that gave rise to When a Stranger Calls. Here’s how he ends it:

Just then a door upstairs opened. A man they had never seen before started down the stairs toward them. As they ran from the house, he was smiling in a very strange way. A few minutes later, the police found him there and arrested him.

As adults, we know what might cause a stranger who’s spent the evening hiding in a house, menacing a babysitter and the three little children she’s been watching, to smile in a very strange way. Indeed, Schwartz states repeatedly, in introductions to the volumes and chapters and in the notes and sources sections at the back of each volume, that scary stories about the non-supernatural are a way for young people to warn each other of the dangers the real world contains once they leave the protection of their parents–a homeopathic remedy for all-too-real fears, if you will. But within the context of the story itself, the man’s motives and bizarre behavior–that strange smile, his apparent lingering long enough for the police to “find him there and arrest him”–is a mystery, both tantalizing and repellent. It’s up to the young reader to fill in the blanks, and nothing good’s going in them.

But it’s also worth noting that Gammell and Schwartz display a sly sense of humor in a lot of their work here as well, befitting the funny-scary tone of a lot of these summer-camp and tall-tale-derived stories. I’m thinking of the subtly grinning alligator with the human hand who accompanies a story of shapeshifting swimming fanatics that ends with the sentence “Everybody knows there aren’t any alligators around here.” Or of the juxtaposition of the extravagantly bloody, elegantly gesturing hand that accompanies “The Ghost with the Bloody Fingers” with the downright goofy story itself, which ends with a guitar-playing hippie obliviously telling the sanguine specter to “Cool it, man! Get yourself a Band-Aid.” This stuff works as a relief valve for the out-and-out scary stuff, obviously. But it also shows just how deft both writer and artist are in treading that liminal area–between funny-weird and funny-haha, between fact and fiction, between popcorn-spilling scary and afraid to get up and go to the bathroom at night scary–where all these folk tales dwell.

One last thing: Schwartz comes up with the best titles! Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark itself is brilliantly matter-of-fact, but the section and story titles really get good in vol. 2: “When She Saw Him, She Screamed and Ran,” “Something Was Wrong,” “A Weird Blue Light,” “Somebody Fell from Aloft,” “She Was Spittin’ and Yowlin’ Just Like a Cat,” “When I Wake Up, Everything Will Be All Right”…More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark is the best collection of titles this side of early Gang of Four–just one more delight to be found in this treasure of a book.

Tags: comics, comics reviews, Comics Time, reviews

3 Responses to Not Comics Time: Scary Stories Treasury