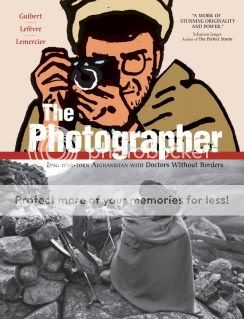

The Photographer

Didier Lefevre, story/photographs

Emmanuel Guibert, writer/artist

Frederic Lemercier, colors/layouts

First Second, 2009

288 pages

$29.95

The high point of The Photographer is literally the geographical high point of The Photographer. After chronicling a Doctors Without Borders mission into the war-torn country–then occupied by the Soviet Union–lensman Didier Lefevre makes the ill-advised decision to leave his more experienced Western colleagues and return through the mountains to Pakistan alone. Abandoned by guides who barely knew the way themselves, Lefevre finds himself stranded at the summit of a mountain pass. In the gloom he desperately tries to make it through by nightfall, and is reduced to beating his exhausted, dying horse until he realizes neither of them can go any further. He bivouacs beneath his horse’s body, melting snow in his mouth in an attempt to stay hydrated, cursing his recklessness and the fecklessness of his escorts. Realizing that he will most likely never make it down the other side of the mountain, he writes a note to his girlfriend and then takes the most beautiful, dramatic, and chilling photographs of his journey, capturing his emaciated horse and the nightmarish wasteland that surrounds them, believing in his heart that they are the last things he will see. In the several pages that chronicle this most dire stretch of Lefevre’s memoir, artist Emmanuel Guibert manages to capture the photographer’s initial panic at being left alone in an unfamiliar place, contrasting his nervous movements and increasingly desperate drive to move on against the cold and motionless stones of the land and small dwelling where he was abandoned. And as Lefevre and his horse reach what he believes to be their final resting place, they are depicted solely in silhouette, black against the icy twilight blues provided by colorist Frederic Lemercier. The effect is a perfect evocation of Lefevre’s Sisyphean plight–frantic effort colliding with unyielding futility and ultimately despair. Gorgeous, frightening, powerful comics.

Alas, it’s one of the only sequences in the whole of The Photographer‘s 288 pages to which any of those four words apply. The story of Lefevre’s trip into and out of Afghanistan is plodding journey through a featureless wash of minutiae about his companions, their hosts, their jobs, and the land. Obviously, the choice to leech the proceedings of nearly any drama–save for Lefevre’s near-death at the mountaintop and a trio of gut-punch accounts of war-wounded children, nothing cuts through the haze of tedious detail–was a conscious one, meant to evoke the reality of life in a desperately poor and brutalized country, and how no grand Orientalist gestures are possible, only the quotidian work of traveling there, setting up shop, and treating those who can be treated. However, a flawless evocation of boredom is still boring.

Meanwhile, memoirists of conflict like Joe Sacco and Art Spiegelman have shown that dull horror can make for compelling comics. But Guibert’s work here is tough to classify as comics at all. Yes, there are panels, word balloons, caption boxes, but his visual contribution is essentially an unending series of stiff minimalist portraits that look like they were produced with a photoshop filter, or one of those dreadful animation projects that take live action footage and boil them down to a “cartooned” style. They demonstrate the story rather than tell it. Even on top of Guibert and layout artist Frederic’s lack of attention to image-to-image flow or to the composition of a page, big blocks of narrative text and the interspersal of Lefevre’s actual photographs all but prevent the effects of accumulative or juxtaposed meaning that are so crucial to the book’s nominal medium of comics. Backgrounds are frequently dropped altogether, replaced with a baffling, uncommunicative palette of pea green and acidic yellow; one rare sequence where backgrounds were present stands out for its wrongheadedness, with rocky terrain all but obliterating the conversation in which Lefevre argues the head of his expedition into letting him return by himself. That Guibert had it in him to produce that knockout climax makes the lack of energy and life in the rest of the book all the more depressing. Nobly intentioned though it may be, bad comics is bad comics.

Tags: comics, comics reviews, Comics Time, reviews

One Response to Comics Time: The Photographer