Posts Tagged ‘Pantheon’

The Four Horsemen

September 26, 2012I interviewed Jaime Hernandez, Chris Ware, Daniel Clowes, and Gilbert Hernandez for Rolling Stone. Comics game Mount Rushmore.

(photo by Meredith Rizzo)

The 20 Best Comics of 2011

January 1, 201220. Uncanny X-Force (Rick Remender and Jerome Opeña, Marvel): In a year when the ugliness of the superhero comics business became harder than ever to ignore, it’s fitting that the best superhero comic is about the ugliness of being a superhero. Remender uses the inherent excess of the X-men’s most extreme team to tell a tale of how solving problems through violence in fact solves nothing at all. (It has this in common with most of the best superhero comics of the past decade: Morrison/Quitely/etc. New X-Men, Bendis/Maleev Daredevil, Brubaker/Epting/etc. Captain America, Mignola/Arcudi/Fegredo/Davis Hellboy/BPRD, Kirkman/Walker/Ottley Invincible, Lewis/Leon The Winter Men…) Opeña’s Euro-cosmic art and Dean White’s twilit color palette (the great unifier for fill-in artists on the title) could handle Remender’s apocalyptic continuity mining easily, but it was in silent reflection on the weight of all this death that they were truly uncanny.

19. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 3: Century #2: 1969 (Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill, Top Shelf/Knockabout): I’ll admit I’m somewhat surprised to be listing this here; I’ve always enjoyed this last surviving outpost of Moore’s comics career but never thought I loved it. But in this installment, Moore and O’Neill’s intrepid heroes — who’ve previously overcome Professor Moriarty, Fu Manchu, and the Martian war machine — finally succumb to their own excesses and jealousies in Swinging London, allowing a sneering occult villain to tear them apart with almost casual ease. It’s nasty, ugly, and sad, and it’s sticking with me like Moore’s best work.

18. The comics of Lisa Hanawalt (various publishers): As I put it when I saw her drawing of some kind of tree-dwelling primate wearing a multicolored hat made of three human skulls stacked on top of one another, Lisa Hanawalt has a strange imagination. And it’s a totally unpredictable one, which is what makes her comics – whether they’re reasonably straightforward movie lampoons or the extravagantly bizarre sex comic she contributed to Michael DeForge and Ryan Sands’s Thickness anthology, as dark and damp as the soil in which its earthworm ingénue must live – a highlight of any given day a new one pops up.

17. Daybreak (Brian Ralph, Drawn and Quarterly): Fort Thunder’s single most accessible offspring also proves to be its bleakest, thanks to an extended collected edition that converts a rollicking first-person zombie/post-apocalypse thriller into a troubling meditation on the power of the gaze. Future artcomics takes on this subgenre have a high bar to clear.

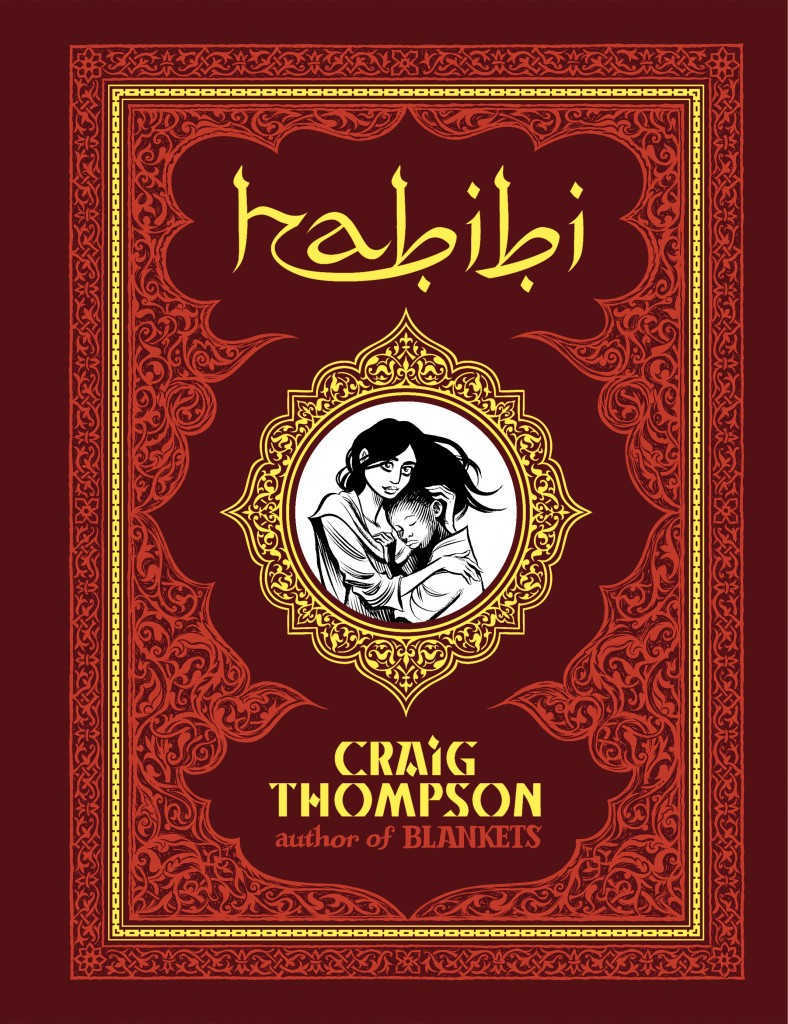

16. Habibi (Craig Thompson, Pantheon): It’s undermined by its central characters, who exist mainly as a hanger on which this violent, erotic, conflicted, curious, complex, endlessly inventive coat of many colors is hung. But as a pure riot of creative energy from an artist unafraid to wrestle with his demons even if the demons end up winning in the end, Habibi lives up to its ambitions as a personal epic. You could dive into its shifting sands and come up with something different every time.

15. Ganges #4 (Kevin Huizenga, Coconino/Fantagraphics): Huizenga wrings a second great book out of his everyman character’s insomnia. It’s quite simple how, really: He makes comics about things you’d never thought comics could be about, by doing things you never thought comics could do to show you them. Best of all, there’s still the sense that his best work is ahead of him, waiting like dawn in the distance.

14. The Congress of the Animals (Jim Woodring, Fantagraphics): The potential for change explored by the hapless Manhog in last year’s Weathercraft is actualized by the meandering mischief-maker Frank this time around. While I didn’t quite connect with Frank’s travails as deeply as I did with Manhog’s, the payoff still feels like a weight has been lifted from Woodring’s strange world, while the route he takes to get there is illustrated so beautifully it’s almost superhuman. It’s the happy ending he’s spent most of his career earning.

13. Mister Wonderful (Daniel Clowes, Pantheon): Speaking of happy endings an altcomix luminary has spent most of his career earning! Clowes’s contribution to the late, largely unlamented Funny Pages section of The New York Times Magazine is briefly expanded and thoroughly improved in this collected edition. Clowes reformats the broadsheet pages into landscape strips, eases off the punchlines and cliffhangers, blows individual images up to heretofore unseen scales, and walks us through a self-sabotaging doofus’s shitty night into a brighter tomorrow.

12. The comics of Gabrielle Bell (various publishers): Bell is mastering the autobiography genre; her deadpan character designs and body language make everything she says so easy to buy – not that that would be a challenge with comics as insightful as her journey into nerd culture’s beating heart, San Diego Diary, just by way of a for instance. But she’s also reinventing the autobiography genre, by sliding seamlessly into fictionalized distortions of it; her black-strewn images give a somber, thoughtful weight to any flight of fancy she throws at us. What a performance, all year long.

11. The Armed Garden and Other Stories (David B., Fantagraphics): Religious fundamentalism is a dreary, oppressive constant in its ability to bend sexuality to mania and hammer lives into weapons devoted to killing. But it has worn a thousand faces in a millennia-long carnevale procession of war and weirdness, and David B. paints portraits of three of its masks with bloody brilliance. Focusing on long-forgotten heresies and treating the most outlandish legends about them as fact, B.’s high-contrast linework sets them all alight with their own incandescent madness.

10. Too Dark to See (Julia Gfrörer, Thuban Press): It was a dark year for comics, at least for the comics that moved me the most. And no one harnessed that darkness to relatable, emotional effect better than Julia Gfrörer. Her very contemporary take on the legend of the succubus was frank and explicit in its treatment of sexuality, rigorously well-observed in its cataloguing of the spirit-sapping modern-day indignities that can feed depression and destroy relationships, and delicately, almost tenderly drawn. It’s like she held her finger to the air, sensed all the things that can make life rotten, and cast them onto the pages. She made something quite beautiful out of all that ugly.

9. The comics and pixel art of Uno Moralez (self-published on the web at unomoralez.com): What if an 8-bit NES cut-scene could kill? The digital artwork of Uno Moralez — some of it standard illustrations, some of it animated gifs, some of it full-fledged comics — shares its aesthetic with The Ring‘s videotape or Al Columbia’s Pim & Francie: a horror so cosmically black, images so unbearably wrong, that they appear to have leaked into and corrupted their very medium of transmission. Moralez fuses crosses the streams of supernatural trash from a variety of cultures — the legends and Soviet art of his native Russia, the horror and porn manga of Japan, the B-movies and horror stories of the States, the formless sensation aesthetic of the Internet itself — into a series of images that is impossible to predict in its weirdness but totally unflagging in its sense that you’d be better off if you’d never laid eyes on it. I can’t wait to see more.

8. The comics of Michael DeForge (various publishers): The last time you saw a cartoonist this good and this unique this young, you were probably reading the UT Austin student newspaper comics section and stumbling across a guy named Chris Ware. All four of DeForge’s best-ever comics — his divorced dad story in Lose #3, his shape-shifting/gender-bending erotica in Thickness #2, his self-published art-world fantasia Open Country, and his gorgeously colored body-horror webcomic Ant Comic — came out this year, none of them looking anything at all like anything you could picture before seeing your first Michael DeForge comic. It’s almost frightening to think where he’ll be five years from now, ten years from now…or even just this time next year.

7. The comics and art of Jonny Negron (various publishers): What if someone took Christina Hendricks’s walk across the parking lot and trip to the bathroom in Drive and made an entire comics career out of them? That is an enormously facile and reductive way to describe the disturbing, stylish, sexy, singular work of Jonny Negron, the breakout cartoonist of the year, but it at least points you in the right direction. No one’s ever thought to combine his muscular yet curiously dispassionate bullet-time approach to action and violence, his Yokoyama-esque spatial geometry, his attention to retrofuturistic fashion and style, his obvious love of the female body in all its shapes and sizes, and his ambient Lynchian terror; even if they had, it’d be tough to conceive of anyone building up his remarkable body of work in such a short period of time. Open up your Tumblr dashboard or crack an anthology (Thickness, Mould Map, Study Group, Smoke Signal, Negron and Jesse Balmer’s own Chameleon), and chances are good that Negron was the weirdest, best, most coldly beautiful thing in it. It’s like a raw, pure transmission from a fascinating brain.

6. The Wolf (Tom Neely, I Will Destroy You): Neely’s wordless, painted, at-times pornographic graphic novel feels like the successful final draft to various other prestigious projects’ false starts. It’s a far less didactic, more genuinely erotic attempt at high-art smut than Dave McKean’s Celluloid; a less self-conscious, more direct attempt at frankly depicting both the destructive and creative effects of sex on a relationship via symbolism than Craig Thompson’s Habibi; a blend of sex and horror and narrative and visual poetry and ugly shit and a happy ending that succeeds in each of these things where many comics choose to focus on only one or two.

5. The Cardboard Valise (Ben Katchor, Pantheon): Prep your time capsules, folks: You’d be hard pressed to find an artifact that better conveys our national predicament than Ben Katchor’s latest comic-strip collection, a series of intertwined vignettes created largely before the Great Recession and our political class’s utter failure to adequately address it, but which nonetheless appears to anticipate it. Its message — that blind nationalism is the prestige of the magic trick used by hucksters to financially and culturally ruin societies for their own profit — is delightfully easy to miss amid Katchor’s remarkable depictions of lost fads, trends, jobs, tourist attractions, and other detritus of the dying American Century. He’s the very most funnest Cassandra around.

4. Love from the Shadows (Gilbert Hernandez, Fantagraphics): I picture Gilbert Hernandez approaching his drawing board these days like Lawrence of Arabia approaching a Turkish convoy: “NO PRISONERS! NO PRISONERS!” In a year suffused with comics funneling pitch-black darkness through a combination of sex and horror, none were blacker, sexier, or more horrific than this gender-bending exploitation flick from Beto’s “Fritz-verse.” None also functioned as a rejection of the work that made its creator famous like this one did, either. Not a crowd-pleaser like his brother, but every bit as brilliant, every bit as fearless.

3. Garden (Yuichi Yokoyama, PictureBox): Like a theme park ride in comics form — with the strange events it chronicles themselves resembling a theme park ride — Yokoyama’s book is a breathtaking, breathless experience. Alongside his anonymous but extravagantly costumed non-characters, we simply go along for the ride, exploring Yokoyama’s prodigious, mysterious imagination as he concocts a seemingly endless stream of increasingly strange interfaces between man and machine, nature and artifice. As a metaphor for our increasingly out-of-control modern life it’s tough to top. As pure thrilling kinetic cartooning it’s equally tough to top.

2. Big Questions (Anders Nilsen, Drawn & Quarterly): Last year, I wrote that if the collected edition of Nilsen’s long-running parable of philosophically minded birds and the plane crash that turns their lives upside-down didn’t top my list whenever it came out, it must have been some kind of miracle year. Turns out that it was. But you’d pretty much have to create a flawless capstone to a thirty-year storyline of neer-peerless intelligence and artistry to top this colossal achievement. Nilsen’s painstaking, pointillist cartooning and ruthless examination of just how little regard the workings of the world have for any given life, human or otherwise, marks him as the best comics artist of his generation, and solidifies Big Questions‘ claim as the finest “funny animal” comic since Maus.

1. Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 (Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, Fantagraphics): Gilbert got his due elsewhere on my list, so let’s ignore his contribution to this issue, which advance the saga of his bosomy, frequently abused protagonist Fritz Martinez both on and off the sleazy silver screen. Instead, let’s add to the chorus praising Jaime’s “The Love Bunglers” as one of the greatest comics of all time, the point toward which one of the greatest comics series of all time has been hurtling for thirty years. In a single two-page spread Jaime nearly crushes both his lovable, walking-disaster main characters Maggie and Ray with the accumulated weight of all their decades of life, before emerging from beneath it like Spider-Man pushing up from out of that Ditko machinery. You can count the number of cartoonists able to wed style to substance, form to function, this seamlessly on one hand with fingers to spare. A masterpiece.

Comics Time: Habibi

September 20, 2011Habibi

Craig Thompson, writer/artist

Pantheon, September 2011

672 pages, hardcover

$35

Buy it from Amazon.com

Fifteen observations about Craig Thompson’s Habibi:

1. This is not a book about Islam. It’s not about any varieties of Islam — contemporary, ancient, fundamentalist, militant, or otherwise. It’s a book infused with Islamic art, culture, thought, and religious beliefs, certainly, but it’s not about Islam. This is another way of saying it’s not about 9/11, al Qaeda, Iraq, Afghanistan, Palestine, Iran, any specific Muslim countries, Muslims in America, uniquely Muslim varieties of misogyny, the Arab Spring, or any other contemporary news-story topic. I first talked to Thompson about his plans for Habibi in the summer of 2003, and in that context and over the course of many of the years to follow it was tough to think about the book without thinking of it one or more of these ways, but no, that’s not what it’s about.

2. This is a book that uses Islam to do other things. On a visual level, it gives Thompson a set of design elements, from calligraphy to ornamentation to architecture to dress to geometrical art, from which he can build a coherent visual world for his vaguely fantastical/post-apocalyptic/dystopian story. Not coincidentally these elements dovetail with his preexisting preoccupations as an artist, from swooping fabrics to obsessive-compulsive design filigrees to religious iconography.

3. It follows that the book is consciously, knowingly Orientalist, as you’d expect and hope of a book that’s using actual Islamic art as bricks in a fantasy world-building project. It’s got an Arabian Nights vibe. Thompson’s invoked Edward Said on this score and everything. To the extent that potentially problematic caricatures of Arab and African race are involved, and they are, they are at least consciously evoked.

4. Islam also provides Thompson with a back door into talking about religion and God — even recognizably Christian elements thereof, thanks to the presence in Islam of Jesus, Solomon, Abraham et al — without needing to rely on the brand of American evangelical Christianity in which he was immersed growing up and which he’s already explored in Blankets. At times the commonality between the issues he discusses in the two books is quite striking. For example, there’s a plotline here about how the bifurcation of Islam and Judaism/Christianity can be traced back to which son you believe Abraham was supposed to sacrifice, Isaac or Ishmael, that’s basically just Blankets‘ bit on scriptural malleability (“The Kingdom of God is within or around you”) blown up to world-historical scale. The impact of religious belief on the development of adolescent sexuality is a centerpiece of both books as well.

5. This is a book about sex. Even if there’s nothing in it that would earn the book anything more than an ‘R’ rating, it works through some violently ambiguous and conflicted feelings about sex in relatively explicit fashion. It took my wife reminding me that Craig first described the book as starring “a eunuch and a prostitute” to help me crystallize that, but there it is. And it makes sense, given the play-it-to-the-balcony tone of Thompson’s previous book, Blankets, and its autobiographical protagonist’s all-or-nothing approach to falling in love and making art, that this book would coalesce around those two poles as well. It is very frankly about the liberating and destructive power of both desire and the denial of desire. (To hearken back to the Arabian Nights element, here’s a tell: Instead of delighting the king with her stories for night after night under penalty of death, the central female character must delight him with sex.)

6. This is a book about many other issues that overlap with or orbit around sex in the popular imagination. They’re not sex, but they’re talked about in the same breath more often than not. They include rape, molestation, prostitution, pregnancy and childbirth, gender, misogyny, a panoply of queer identities, self-injury, puberty, motherhood, male-female friendships, sex and race, sex and organized religion, sex and spirituality, sacrifying sex/orientation/gender, masculinity and femininity…

7. The emotional and physical stakes for the characters are much higher than they are in any of Thompson’s previous works. This is established within the first few pages, in which a child is raped. A bloody sheet is held up to the child and the audience, the blood of her vagina on the blank white fabric equated with the letter-writing in Chunky Rice; the footprints on snow and drawings on paper of Blankets; the act of Creation itself — “From the Divine Pen fell the first drop of ink.” Violence and abuse are the lifeblood of the story.

8. Thompson’s art is much, much denser here than I’ve ever seen it before. It’s still lush and lovely on a surface level, his line still swoops and curves in a fashion he’s explicitly compared to handwriting, but there are more panels on the page, more black in the panels, few of the vast fields of white Blankets was known for, and few of its splash pages too. Decorative patterns of intricate detail are copied from Islamic texts by hand, and drawn repeatedly until they cover almost all the available space on a given page, also by hand. It’s a much tougher book for your eyes to breeze through.

9. Maybe the best way to symbolize that is in the new panorama Thompson has added to his repertoire. He’s said, and promotional art for the book has made use of the fact, that Good-Bye, Chunky Rice had the ocean, Blankets had the snow, and Habibi has the desert. That’s true, but Habibi heavily features vistas of another sprawling, enveloping sea: a man-made sea of garbage. It’s as dense and detailed and chaotic as the water, snow, and sand are unified and simplified.

10. The book is designed. Designed in the Watchmen symmetrical-issue sense. Each of its nine chapters corresponds to a box in the Islamic religious/mathematical talisman known as a magic square — a sort of spiritual sudoku — and its corresponding letter of the alphabet. Each corresponds to a specific topic, and a specific prophet of Islam used to illuminate that topic. But unlike Alan Moore, Thompson doesn’t foreground his machinations. This stuff is present, but in its way it’s beside the point. I didn’t even notice.

11. In much the same way that light, electricity, and information functioned as the stuff of life in Grant Morrison’s Final Crisis, fluid is the stuff of life here. Water is crucial to the various societal strata’s survival within the drought-stricken world of the story. Blood is crucial to nearly all of the book’s depictions of both sex and violence, the fuel of human physicality. Ink is crucial to the characters’ understanding of the nature of God and the world via holy texts and art, and to the author’s understanding of what the hell he’s been doing for the past eight years. There’s less semen or vaginal secretion than you’d think, but otherwise it’s a book about fluids, and fluidity. The greatest sin is staunching the flow, which is done in various ways — a metaphor that extends from environmentalism to art to, of course, spirituality and sexuality.

12. The relative lack of emphasis on sexual fluids is a leading indicator of where the book ultimately pulls an important punch. There’s a revelation, an exposure, toward the end of the book that we readers do not get to see. Since the book confronted virtually everything else it tackled so head-on, since it was so in-your-face about violence and sexuality, you really feel this revelation’s visual absence. Which is maybe appropriate, given what’s being revealed, I dunno. But it left me wondering “Why didn’t he show that?”, in a way that suggests it’s a misstep.

13. The book contains two of the toughest depictions of mental illness I’ve come across in comics. One in particular involved postpartum depression and was deeply sad to me. The other comes hot on the heels of the book’s single most unpleasant depiction of the cruel fate of children in this world. Actually, nearly everything involving children is rough stuff here. There’s not a lot of time for innocence.

14. The book contains two pretty rollicking action sequences. If you’ve read as many lousy action comics as I have, it ought to be a pretty great pleasure for you to watch an artist with Thompson’s attention to environment, layout, movement, and pacing choreograph chase scenes and fight scenes. It definitely was for me. And these sequences had the secondary function of release valve for the dense and emotionally oppressive material they helped break up.

15. Actually, the more I think about it, the more I think Habibi is a book of sequences. Maybe this is reinforced by Thompson’s non-linear storytelling, with his male and female leads’ stories shifting backward and forward in time independent of one another, a technique that emphasizes discreet sequences over the overall flow of the larger narrative. But the bathtub sequence (very successful), the dam sequence (this is perhaps the book’s climax, and I’m not sure it’s successful), the garbage man sequence, the childbirth sequence, the eunuchs sequence, the conflicting stories of Abraham’s aborted sacrifice — these are what stick out to me, embedded in the bigger picture. They’re what will draw me back into the book, moving backward and forward through the work of a cartoonist working out his personal obsessions on the grandest canvas imaginable.

Comics Time: The Cardboard Valise

March 7, 2011The Cardboard Valise

Ben Katchor, writer/artist

Pantheon, March 2011

128 pages, hardcover

$25.95

Buy it for damn near 50% off right now at Amazon.com

Comics Time: Bodyworld

January 12, 2011Bodyworld

Dash Shaw, writer/artist

Pantheon, April 2010

384 pages, hardcover

$27.95

Read it for free at DashShaw.com

Buy it from Amazon.com

Did everyone know this was a comedy but me? I actually put off reading Dash Shaw’s, what is it now, second magnum opus and first full-length science-fiction graphic novel because I find the formal experimentation of his SF stuff intimidatingly difficult to parse even in short-story format — surely a 400-page webcomic turned fat hardcover would fuck my shit up, right? But while Shaw’s shorts frequently swap complexity for clarity, at least for me, Bodyworld is a breeze to read. Part of that’s physical — the fun of its vertical layout, kicking back and flipping the pages upward on your lap or desk. But mostly it’s that the thing reads like a quirky indie-movie genre-comedy — think a mid-00s Charlie Kaufman joint, or Duncan Jones’s Moon with more laffs ‘n’ sex. We follow one helluva protagonist, Professor Paulie Panther, a cigarette-smoking, plain white tee-clad schmuck who wouldn’t look out of place hanging out with Ray D. and Doyle in a Jaime Hernandez comic and who has harnessed his prodigious appetite for doing drugs and not doing work into a career as a field-tester for hallucinogenic plants. Basically, he travels around the world smoking anything that looks unusual. For the purposes of Bodyworld that has taken him to Boney Borough, a Thoreau-like enclave whose planners mixed unfettered nature right into the zoning laws as a response to a horrific decades-long Second Civil War that began ravaging the United States, it seems, following the installation of George W. Bush. There he discovers a smokable plant that gives its users a telepathic bond with anyone in their proximity, leading to disastrous romantic entanglements and disentanglements with the local high school’s hot teacher, its prom king, and his girlfriend. But there’s more to the plant that meets the eye, and a Repo Man-style series of surreal/slapstick/science-fictional escalations leads to a funny but still black and potentially apocalyptic ending, like the Broadway version of Little Shop of Horrors.

Bodyworld‘s webcomic incarnation was famous for its vertical scroll, and for my money it’s recreated enjoyably by the vertical flip in the book format. What surprised me about Shaw’s other formal innovations here is how relatively restrained they are. You don’t really need to keep track of his complex, color-coded grid maps of Boney Borough or the school to understand what’s going on where, and the to the extent that he plays with overlaps and repetition and color and so on it’s mostly done to convey the hallucinogenic mind-melding engendered by the drug, quite effectively, at that. Moreover, I’ve often found his character designs hard to parse and hard to like — something about the way they’re constructed from purposely ugly swirls and swoops just gives me prosopagnosia — but his quartet of leads and dozen or so prominent supporting characters are by far his strongest ever in this area; you really can get who they are and what they’re about just by looking at them, which prospect is not at all unpleasant, either. And while some of the yuks fall flat (particularly with the town sheriff late in the game), it’s for the most part a dryly witty, occasionally laugh-out-loud funny comedy, with finely observed humor about high schoolers, teachers, druggies, hoary sci-fi tropes, and the sort of shiftless ne’er-do-wells you enjoy spending an evening with when your buddy brings them along. In short, it’s a prodigiously ambitious cartoonist plying the various tricks of his trade just to tell a good story you can catch some weekend afternoon and then chat about with friends at the diner afterwards.

Comics Time: X’d Out

December 15, 2010 X’d Out

X’d Out

Charles Burns, writer/artist

Pantheon, October 2010

56 pages, hardcover

$19.95

Buy it from Amazon.com

Even more so than in Black Hole, the images Charles Burns creates here are small, dense, and inescapable. An abundance of tightly gridded pages filled with repetitive head-on close-ups or point-of-view shots. An avoidance of establishing shots unless they’re designed to mimic what our protagonist Doug sees, nine times out of ten with him on the left-hand side of the panel, our eyes’ transit across the image locked to his own. Narrow rectangular panels consisting of nothing but unbroken fields of disembodied color — some conveying something clear, like maroon panels for the drug-induced unconsciousness brought on by maroon pills, others whose meanings are less clear but no less demanding of our attention, denying us access to anything but that particular color for that particular panel. The recurring use of photographs, sealing a single moment in time. The arising of recurring images unbidden into Doug’s head, single glimpses of scars, cigarette burns, black cats, fetuses, a nude, holes. The way those images weave themselves in and out of both his ostensible real life amid art-punks in the late ’70s and his dream-state/hallucination/extradimensional excursion/whatever it is, and the way that implies that they’re some sort of indelible fabric binding his existence together, like his life could be reduced to these eggs and holes in the wall and black-haired women and black-haired cats and drowning animals. The images are stronger for Burns’s more intense focus on the finite and discrete, on individual moments and objects. Their gravitational pull colors and distorts everything else we see. In much the same way that Doug’s plastic Tintin mask carves away extraneous detail until all we’re left with is the idea of a face, X’ed Out is a story of how both memory and dreams boil our lived experience down to the iconic essentials, however unpleasant they may be. This book could just as easily and accurately have been called 0’d In.