Posts Tagged ‘Nine Inch Nails’

Music Time: Nine Inch Nails – Ghosts V: Together & Ghosts VI: Locusts

April 1, 2020The fifth and sixth volumes of Ghosts (subtitled Together and Locusts respectively) return to the atmospheric terrain now familiar from Reznor and Ross’ soundtrack work: buzzy ambience, simple melodic hooks, an emotional palette that vacillates between peace and dread. But rather than soundtracking an on-screen drama, they arise from the very real COVID-19 pandemic and its society-wide remedy, social distancing. The musicians say that the current crisis was the reason they completed the two records in the first place, “as a means of staying somewhat sane.” As such, Ghosts V-VI—released for free less than two months after the World Health Organization declared a global health emergency—are very likely the first major albums to have been inspired by the coronavirus crisis.

The 33 Best Industrial Albums of All Time

June 17, 201929. Lords of Acid – Voodoo-U (1994)

Debuting with 1991’s Lust, Lords of Acid were best known for Belgian new-beat bangers with humorously filthy lyrics, the kind of club floor-fillers that hormonal drama club kids could put on their mixtapes. But the rampaging breakbeats, screeching-siren vocals, and double-barreled guitar and keyboard riffs of Voodoo-U were less funny and more frightening. The needles-in-the-red sound was as loud, lewd, and cavernous as the come-hither cover art by the artist COOP, which depicts a fluorescent-orange orgy in the bowels of Hell. Indeed, standouts like “The Crablouse” (a paean to the orgasmic prowess of pubic lice) and the explicitly witchy title track lent the demonic urgency of a summoning ritual to music for people who just really wanted to fuck other people in black mesh tops and vinyl pants. Go ahead, judge this one by its cover.

Music Time: Trent Reznor/Atticus Ross – Bird Box (Abridged) Original Score

January 16, 2019Starting with 2008’s sprawling collection of instrumental work Ghosts I-IV (released under the Nine Inch Nails aegis) and accelerating with 2010’s Oscar-winning score for David Fincher’s The Social Network, the instrumental side of Trent Reznor has effectively shared equal billing with the more traditional industrial rock that made him a superstar. Never one for half measures, Reznor clearly sees the film-soundtrack work done alongside his longtime composing partner Atticus Ross as a chance to flex. “We aim for these to play like albums that take you on a journey and can exist as companion pieces to the films and as their own separate works,” Reznor wrote recently. He’s not kidding: The duo’s score for Fincher’s 2011 film The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, for instance, is 15 minutes longer than the movie itself.

In announcing the release of Bird Box, the score for Netflix’s treacly Sandra Bullock survival-horror film of the same name, Reznor described it as a way of presenting the audience with “a significant amount of music and conceptual sound” that didn’t make the film’s final cut. Even then, that “Abridged” parenthetical in the title points toward “a more expansive” version of the album due later this year. It’s just as well since what Reznor and Ross have created is better than the movie they created it for. It does exactly what good soundtracks are capable of doing, and what they expressly intend for it to do: Emerge as a rewarding experience in its own right.

I reviewed Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross’s Bird Box score for Pitchfork.

Nine Inch Nails: Add Violence [EP]

July 26, 2017The EP’s final track is both the strongest and strangest. “The Background World” appears to be a slinky electronic groove that might conclude a big-budget Hollywood thriller, serving the same function as Moby’s “Extreme Ways” in the Bourne movies, or Reznor and Ross’ cover of Bryan Ferry’s “Is Your Love Strong Enough?” with their frequent collaborator (and Reznor’s wife) Mariqueen Maandig in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. Yet the lyrics are bluntly bereft of sequel-ready optimism: “There is no moving past/There is no better place/There is no future point in time/We will not get away.” Reznor’s detractors tend to mock this sort of sentiment, but in the year of our Lord 2017, who’s laughing now?

The song’s formal moments are even more intimidating. It repeats the same awkwardly edited instrumental snippet—a brief empty hiccup separating each iteration—over fifty times. Seven minutes and thirty-nine seconds of the song’s eleven minute, forty-four-second runtime are eaten up as the segment plays out over and over, each new version a degraded facsimile of the last, until only static remains of the original riff and rhythm. Like an image run through a Xerox machine until it’s no longer recognizable, this makes Reznor’s Hesitation Marks–era worry that he’s just “a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a” legitimate entity real and audible. Its audaciousness would make David Lynch himself proud. As Reznor promises additional work to come in the near future, it gives his listeners reason to hope, no matter how hopeless he himself becomes.

I reviewed the new Nine Inch Nails record for Pitchfork. Proud to be covering this band for this site in this way.

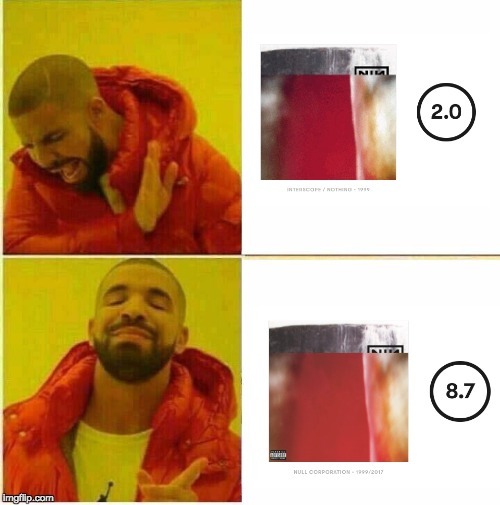

Nine Inch Nails: ‘The Fragile (2017 Definitive Edition)’ / ‘The Fragile: Deviations 1’

January 11, 2017The Fragile arrived a stylistic turning point, emerging at the point where the “alternative” sobriquet fell out of fashion and “indie” achieved dominance. Today, though, reservations about the lyrics’ outré confessionality and the music’s jam-packed, everything-plus-the-kitchen-sink gigantism seem positively quaint. (Don’t care for titanically hyper-produced albums stuffed with uncomfortably intimate and self-mythologizing lyrics about your emotional world falling apart? Tell it to Lemonade.) The Fragile may lack the tightness of Nine Inch Nails’ other highlights: the concise fury of Broken, the inexorable depressive logic of The Downward Spiral, the late-career professionalism of Hesitation Marks. But it takes the emotional distress that gives it its title and transmutes it into something colossal, defiant, and resilient. Listen to it at your strongest or your weakest (and I’ve certainly done both) and it will offer you a sonic signature commensurate with the power of what you feel inside.

tl;dr version:

Music Time: Nine Inch Nails, Barclays Center, October 14 2013

October 15, 2013Nine Inch Nails’ 20th-century iteration was a matter of excess. It was excess of abandon during the Broken and Downward Spiral period — smashed instruments, trashed dressing rooms, primal screams on the records. And it was excess of ambition during that era’s summary statement, The Fragile — live-in recording studios, Bob Ezrin on the boards, a level of sonic perfectionism that literally drove Trent Reznor to drink.

Since the band’s post-sobriety return with 2005’s With Teeth, however, Nine Inch Nails has been about keeping control. With Teeth pared the act down to a tight, pummeling rock-band model, one that remains a centerpiece of its live shows. Year Zero belied its concept-album dystopia with a quick-and-dirty recording process — a couple of laptops on a tour bus, pretty much. Ghosts may have been an instrumental triple album, but each track was more of a sketch than a song. The Slip blended several of these modes.

The pattern culminated in Hesitation Marks. It’s a throwback to The Downward Spiral and The Fragile in terms of its visual and sonic vibe, but lyrically it’s a contemplation and rejection of the Reznor of that period. It’s about an emotional life he now has control over, and his fear of losing his grip the way he once did. All told, the career trajectory that emerges from juxtaposing these eras evinces a great deal of thought about what this band does and what it means to its architect.

Nine Inch Nails’ live show reflects that care and attention. It starts in full muscular rock-band mode, with stark white lighting that’s equally no-nonsense. When the set expands to encompass more expansive material from Hesitation Marks and The Fragile, a pair of backup singers are added — their first vocals got a big audience pop, since that’s pretty much the last thing anyone expects at a Nine Inch Nails show, but for the most part they serve to unobtrusively shore up and support Reznor’s vocals, which often play off subtle but crucial harmonies or calls-and-responses in the songs’ studio version that have traditionally been lost in live translation.

A digital light show of genuinely stunning sophistication and ambition fleshes out the visuals accordingly, rivaling if not surpassing your widescreen rock band of choice for sheer spectacle. But again, the range of effects is carefully considered, primarily involving shifting digital colors, three-dimensional wire frames, and silhouettes. It’s evocative but non-narrative, designed to command audience attention during lesser-known or more difficult songs.

The lighting cues often get very specific, highlighting individual musicians in frequently unorthodox ways: I think pretty much every trick in the book was used to spotlight drummer Ilan Rubin except an actual spotlight, while one memorable solo from guitarist Robin Finck was reverse-spotlighted, a digital projection sort of burning away to blackness as he played. Bassist Pino Palladino, who takes his on-stage comportment cues from the similarly stoic John Entwistle (whom he’s replaced in the Who), is barely ever lit at all.

And for all its high technology, a couple of its strongest moments were callbacks to the band’s rich design history: a Batsignal-like projection of the classic NIN logo ended the main set during the final notes of “Head Like a Hole,” while the encore’s closing performance of “Hurt” was accompanied by the same black-and-white montage of disturbing images that ran when the band played the song during the Downward Spiral’s arena tour nineteen years ago. It’s a clever way to emphasize the time period during which his relationship with the largest segment of his audience was forged, while connecting it visually to his more recent and forward-thinking work — a capstone for a thoughtful, frequently spectacular show that incorporates the person he was then into the artist he is now.

“I was working with Adrian Belew on some musical ideas”

February 25, 2013Music Time

June 8, 2012I felt like I should again note here that I’m writing about music for my new blog Cool Practice, about songs and videos that read as “cool” to me.

* Beastie Boys – “So What’cha Want”

* Public Enemy – “Fight the Power”

* Country Joe McDonald – “The ‘Fish’ Cheer/I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag”

* Nine Inch Nails – “March of the Pigs”

I hope you like it.

Nine Inch Nails, Live at the Roseland Ballroom, New York City, May 14 1994

November 9, 2011Pinion // Terrible Lie // Sin // March of the Pigs/All the Pigs, All Lined Up // Something I Can Never Have // Closer // Reptile // Wish // Suck // The Only Time // Get Down Make Love // Down In It // Big Man with a Gun // Head Like a Hole /// Dead Souls // Help Me I Am in Hell // Happiness in Slavery

This was the very first concert I ever went to. I had turned 16 a little over two weeks before the show; I had met the girl I would go on to marry two and a half months before that. There were two opening acts. The first was the lipstick lesbian dance act Fem2Fem, who brandished strap-ons on stage. The second was Marilyn Manson; when we saw all the t-shirts at the merch booth we wondered who she was. Listening to the recording now, it’s clear that The Downward Spiral was new enough for songs like “Reptile” to be met with a muted reaction upon their opening notes. “Closer” goes over like gangbusters, though, which means that maybe it’s not the newness of the other songs that earned them a softer reaction, maybe the audience was filled with radio fans. I was really pleased that the audience was apparently so familiar with Queen that they all sang along when the band played “Get Down, Make Love,” only for an older kid to inform me that they’d covered the song on the Sin single. I spent the encore in the “mosh pit” and survived. Trent smashed his keyboard and as the crowd dispersed people were hunting for broken keys on the floor. My folks were so nervous about me being in the city that they sent a car to pick me and my friends up rather than let us take the train home. The car radio was set to WDRE, and I heard “Love Will Tear Us Apart” for the first time. Of the group of three kids I went with, I am now a father, the second is a father-to-be, and the third is dead. It feels like a lifetime ago.

Sleigh Bells, Justin Bieber, Ministry, Nine Inch Nails, and the feelings of a real-live emotional teenager

December 17, 2010I read a couple of interesting things about Sleigh Bells and their excellent album Treats today today. My pal Matthew Perpetua is right to note that unlike a lot of the artists and microgenres that are playing around with how their music is recorded, Sleigh Bells isn’t doing so to evoke the past, but to emphasize the intensity of the present. Yet critics often invoke the past when talking about Sleigh Bells anyway — not in terms of era, a la chillwave and the ’80s, but in terms of age groups, an age group all of us used to belong to: teenagers.

In writing up the record for Pitchfork’s Top 50 Albums of 2010 list, Tom Ewing says: “The most convincing take on Treats— the one which makes emotional sense to me– is that it’s a kind of teenpop: the mess, posturing, chaos, and unrelenting immediacy of an adolescent’s headspace crushed into two-minute blurts.” I don’t find this take convincing at all. Mess and chaos? Sure. But posturing? Not so much.

Here’s what I mean: Two nights ago I was driving home from the middle-school chorus Winter Concert my wife, a music teacher, conducted. Every year she takes requests from the kids and writes her own choral arrangements for pop and rock songs they’d like to perform in the spring concert, and this year, naturally, some girls in her classes requested Justin Bieber. She turned them down flat, because she had literally promised the boys she wouldn’t make them do a Justin Bieber song. Middle school boys, it turns out, haaaaaaaaaaaaaate Justin Bieber, the same way middle school boys have always hated pop culture performed by young men but aimed at young women. In my day I hated the New Kids on the Block and Beverly Hills 90210; a few years later I’m sure it was N’Sync and the Backstreet Boys; today it’s Biebs and Twilight; I know that when I was very young in the early ’80s, I could sense how the older boys hated Duran Duran. Fast forward a few years into full-fledged high-school adolescence and the battle of the sexes angle was less important, but the desperate need to define yourself by what you weren’t into as much as what you were was, if anything, even more keenly felt. Fuck jock music like the Dave Matthews Band and the Grateful Dead, fuck poseurs like the Offspring and Stabbing Westward, fuck even too-cool snobs like Pavement and Sonic Youth. As a kid who very much self-identified as Alternative my story’s no doubt a bit different from those with different tastes, but I think “this is good and THAT SUCKS” is universal for teenagers no matter what genre you’re really into. Even the ballyhooed egalitarianism of Top 40 radio, I think, is predicated on the fun of yelling “ewwww!” and changing the station when that song you can’t stand comes on.

It took me until after I graduated college and discovered David Bowie to free myself from all of this, to be willing to break it all down, to realize that my identity wouldn’t be threatened by an easing of definitional barriers but strengthened by it. Now I’ll try anything, and I write off nothing out of hand, on “principle,” to maintain my posture. (To be clear, I realize this is itself a posture of a sort!) I mean, still fuck the Offspring and Stabbing Westward, but fuck them for not being very good, not for failure to be appropriately authentic, you know?

And so I can appreciate and enjoy Sleigh Bells for all they bring to the table and for all the disparate genres from which they bring it — the bluntest, least subtle beats from hip-hop and riffs from metal and hardcore, the Rainbow Brite sing-songy vocals from disposable girl pop, the meta-trickery with recording and dynamics from noise and industrial. And I’d love to live in a world where a broad swathe of teenagers were open enough to all of that to make “teenpop” an accurate characterization. (As opposed to “pop a small handful of teens might like” — there are always gonna be outliers with good ears, even if they’re not consistently put to use. To pat myself on the back for a minute, I remember bumping into an old high-school classmate on the train and getting to talking about music, and he said to me “Jesus, you listened to Aphex Twin in high school!” with something approaching awe. This was true, and good for me, but at the same time I hated Depeche Mode and New Order.) But that’s certainly not the world we live in. The kids who might get into the aggression and power of the gigantic beats and towering riffs would have no idea what to do with Alexis Krauss, and the kids who might enjoy the sweet singing about wondering what your boyfriend thinks about your braces would turn the thing off the second the distortion kicked in. For pete’s sake, the Sleigh Bells album’s title track alone swipes the guitar sound from both “How Soon Is Now?” and “The Thing That Should Not Be” — in teen terms it’s like if the Hetfields Hatfields invited the McCoys to their family reunion!

It’s a very, very rare pair of teenage ears that can even tolerate liminality, let alone appreciate it. And this is not to say that boundaries can never be blurred — I feel like kids my age were on the leading edge of a cohort that completely collapsed the wall between liking rock and liking rap, even aside from Rage Against the Machine and the Beastie Boys and even before you got to the Limp Bizkits and Linkin Parks; I listened to as much A Tribe Called Quest and Public Enemy as Soundgarden and Alice in Chains. Yet these were all their own lines drawn in the sand, too: “Rap is not pop — if you call it that, then stop,” remember? So maybe this is why the Bieber incident leaped to mind when I read Ewing’s “teenpop” comment: My guess is that the hardest boundary to erase would be the one that separates music that teen listeners feel is gendered in some way. Thus I think the best we adults can do is characterize Sleigh Bells as pop that reminds adults who know better of feeling like a teenager. But — well, you know.

Far, far more convincing to me was Mark Richardson’s earlier Pitchfork review of the record, which compared it to Ministry’s The Land of Rape and Honey, among other mostly less vicious records, in terms of how it expanded his conception of what “loud” could mean in music. I made that same comparison myself the other day. And Ewing himself did too, actually, when he compared the record to the likes of Prodigy and Lords of Acid. These were hugely ear-opening comments for me, helping me understand not just what I was reacting to in Sleigh Bells, but also what I was always enjoyed so much when listening to Psalm 69 or Voodoo-U or whatever the case may be: The thrill! As Matthew put it in his post today, it’s about taking some awesome sound and making it not just sound but feel as awesome as possible — like putting a great colorist on a great superhero artist, you know?

This is the territory where I think we can tease out what makes Sleigh Bells pop — adult pop, but pop — when much of what it’s drawing from really isn’t. Take Ministry. Lately I’ve been listening to the live version of their song “Burning Inside” almost constantly. The insanely ominous beginning actually makes me laugh out loud, it’s so thoughtfully put together in how it conveys cartoonish, apocalyptic evil: Massive bowel-shaking low-end rumbles, portentous pauses, ghostly human voices fading in and out, a warning siren, and finally the clicking and clacking rudiments of a rhythm, all before you’ve heard the first pound on the drum or distorted riff. And once those kick in, forget about it: It’s pure anger and disgust. But the key thing is Al Jourgenson’s vocals, which chant every word on the same not-quite-a-note through a vast field of distortion. They’re not spat out or shouted out, they’re emitted, like one of those disconcerting sci-fi/fantasy images in which some entity blasts energy not out of its fingers or hands or even eyes bout out of its mouth. There’s something robotic or demonic about it — not human at all.

Compare that to Nine Inch Nails’s “Wish,” a not at all dissimilar song and one that invited a lot of derisive comparisons at the time it came out. (I remember reading letters to the editor in the local paper about what a Ministry rip-off Broken was.) The stop-start riff and breakneck tempo and overwhelming hatred for everyone and everything are more or less consistent between the two songs, although as usual Al adds a sort of supernatural/mystical/eschatalogical angle, things raining down from the sky and so on, that it would take Reznor a while to get to. But whereas Jourgenson’s vocals are processed into becoming almost an additional buzzsaw guitar, Reznor is clearly a singer. There’s a body and a soul to what he’s doing; I think that’s what made him a sex symbol and what made Nine Inch Nails, for all its nihilistic aggression and self-loathing, fuck music for a lot of people, whereas Jourgensen’s sex references in Ministry, and even far less dark, more smutty side projects like Revolting Cocks, were almost resolutely non-erotic.

Alexis Krauss, in her way, is doing to the Ministry template of power and loudness what Reznor did to it in his way: She’s humanizing it, making it relatable and accessible to people beyond Ministry’s audience of gleeful misanthropes. With Trent and Alexis, women/men want them and men/women want to be them (take your pick!); I worshiped Al, I connected and still connect (intensely!!!! four exclamation points!!!!) with what he was doing, but I never wanted to be him. Reznor brought personal emotional intensity and erotic heat to the equation, Krauss brings joy, play, what Cosmo Kramer might call “unbridled enthusisasm,” but it’s the same principle: taking this sonic juggernaut and putting the spotlight on its pilot, in so doing conveying the notion that you could sit in that pilot seat yourself.