Posts Tagged ‘Joseph Lambert’

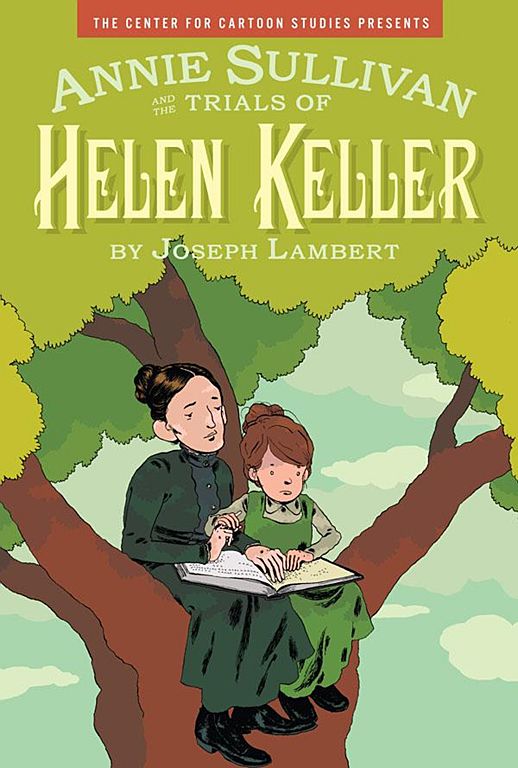

Comics Time: Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller

June 22, 2012Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller

Joseph Lambert, writer/artist

The Center for Cartoon Studies/Disney/Hyperion, March 2012

pages, hardcover

$17.99

Buy it from CCS neighbor the Norwich Bookstore

Buy it from Amazon.com

A dual biography of deaf-blind Helen Keller and her teacher, mentor, guardian, and lifelong companion Annie Sullivan — whose own coming-of-age tale of overcoming near-blindness, abject poverty, orphanhood, loss, lack of education, and a generally piss-poor attitude is depicted in parallel with Annie’s better-known story — Annie Sullivan and the Trials of Helen Keller is the best comics biography since Chester Brown’s Louis Riel. Like Riel, it succeeds, it innovates, as comics as much as it does as biography. It does so with none of the repetitive tics that marred cartoonist Joseph Lambert’s earlier work, here supplanted by the intensity of the story’s central challenge and Lambert’s own clarity of purpose in meeting it. And more than Riel, it’s a work of immense and intimate emotional power, deeply touching and profoundly moving without ever growing maudlin or manipulative.

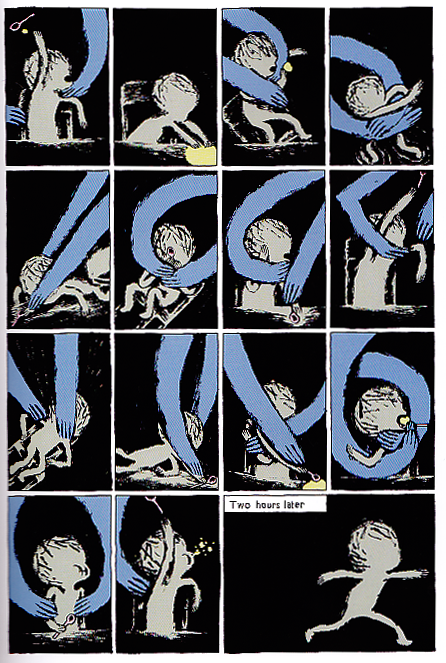

The key visual conceit is Annie’s world: black, comprising her sketchy self-image, objects she encounters rendered in a dull brown, things with which she has any kind of emotionally charged interaction (from her family to food) colored in sidewalk-chalk primaries. Spend more than two seconds thinking about experiencing life like this and it’s harrowing, even horrifying, but Lambert holds back on depicting it as some existential hell, since after all, this is the only life Helen really knows. (She went blind at 19 months of age, and neither she nor her caretakers are sure what, if anything, her brain remembers from its sighted experiences.) Annie’s quest is to get Helen to understand that the hand gestures she forces her to perform when touching new objects or requesting familiar ones aren’t just a game to play, but a way to label these objects, and thus to understand them and their relationships to one another.

Though Lambert’s access via cartooning to Helen’s inner world is unique among depictions of this well-worn story, it’s only through juxtaposition with the more traditionally told tale — the literal wrestling matches bas Annie tries to physically force Helen to learn — that the magnitude of Helen’s struggle becomes clear. Without seeing Helen in all her painfully adorable and vulnerable and angry tousle-haired glory, throwing plates and running into walls and knocking Annie’s teeth out and leaving both teacher and student in (magnificently well-drawn) prostrate exhaustion amid debris-strewn rooms, her famous eureka moment at the well, which we see alternating back and forth between Annie and Helen’s perspectives, would not have the power it does. When big block-lettered NAMES finally emerge into Helen’s mental void, it’s not just WATER or HANDLE or PITCHER or even TEACHER that get their names, it’s the inchoate fury that’s plagued her like an infection all her young life. In this case the diagnosis is the cure. Lambert’s depiction of her almost unbearable excitement at finally getting it, frantically touching and signing out the names of everything at the pump until she reaches “TEACHER” and collapses into an embrace of the woman who effectively gave her a voice and saved her from insanity, is easily the most emotionally moving sequence of comics I’ve read all year. I’m crying just writing about it.

The visual language Lambert develops for Helen’s own developing language isn’t the sum total of his artistic strengths here. Now, for the life of me I’ll never understand how dully acidic, Exorcist-vomit green became the default background color for comics imprints with mainstream aspirations, from Vertigo to First Second, and in this Disney-Hyperion release Lambert overuses that lamentable hue. But it’s more than offset by the stunning Mentos-variety-pack skyscapes and lush green fields and trees of the Keller homestead; the subtle and astute interplay of trademark colors for the two women in Helen’s life, blue Annie and pink Mother; the use of various muted grays, blues, pinks, and yellows to differentiate spacial and temporal settings within Lambert’s not-an-inch-wasted sixteen-panel grids; brief but memorable uses of bright red or high-contrast black and white; and of course the very direct but still very effective depiction of the pre-speech Helen’s world as a black and gray-brown void into which new sensations intrude in synesthetic terror and splendor.

The book culminates in scandal — a minor one in the context of the Sullivan/Keller legend lo these many decades later, but a catastrophic upheaval in the lives of Annie, Helen, and their benefactors at the Perkins Institution for the Blind at the time. The climactic interrogation sequence, in which the school’s instructors grill Helen for hours about a potentially dubious achievement she’s alleged to have made, stands firmly in the grand (inquisitor) tradition ranging from O’Brien and Smith in Ninteen Eighty-Four to the real-life questioning of the West Memphis Three in Paradise Lost. It’s a hugely upsetting and dispiriting scene, one which literally reduces Helen to the sketchy, spectral brown shape running around in the darkness that she was before Annie illuminated her world.

The real trap of it is that it’s precisely that act of illumination that damns Helen in her interrogator’s eyes, and partially in her own. When her life is one great string of discoveries, her joy is unstoppable; when she’s forced to confront how those discoveries were all filtered through one other person, she can no longer trust her own ability to determine where she ends and Teacher begins. Is she the water, or just the pitcher into which someone else’s water was poured? Moreover, the trap is twofold: . Lambert’s third-hand revelation of Annie’s potential deceit is deftly done, and breathtaking in the way it takes what we’d come to see as virtues in “Miss Spitfire” and unveils them as potential faults. Based on everything we’ve seen of her — her desire to get the full credit she deserves, no less but also no more — it’s highly unlikely that she consciously committed the crime of which she stands accused. But also based on everything we’ve seen of her — her defiance, her refusal to be cowed, her sneakiness, her confidence that she’s the smartest person in any given room — her role in the cover-up is all too believable. For Lambert to prove himself capable of character work this subtle and rigorous, character work that complicates and enriches the character rather than reducing them to mere angels or martyrs, in a book that moves from strength to strength visually as well, is almost unfair.

Every year there’s a comic that makes me end my review with the sigh of awestruck resignation: the exclamation “What a comic.” This is my “What a comic” comic of the year to date. It’s stunning. Don’t miss it.

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 22: Fall 2011

December 20, 2011Mome Vol. 22: Fall 2011

Zak Sally, Kurt Wolfgang, Jordan Crane, Chuck Forsman, Steven Weissman, Sara Edward-Corbett, Laura Park, Tom Kaczynski, Joe Kimball, Jesse Moynihan, Josh Simmons, The Partridge in the Pear Tree, Malachi Ward, Eleanor Davis, James Romberger, Derek Van Gieson, Michael Jada, Tim Lane, Nate Neal, Wendy Chin, Anders Nilsen, Tim Hensley, Lilli Carré, T. Edward Bak, Nick Drnaso, Joseph Lambert, Paul Hornschemeier, Sergio Ponchione, Nick Thorburn, Dash Shaw, Ted Stearn, Jim Rugg, Victor Kerlow, Noah Van Sciver, Gabrielle Bell, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds, editor

Fantagraphics, 2011

240 pages

$19.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

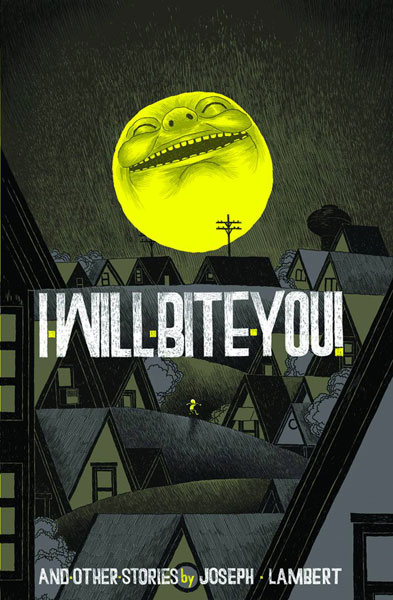

Comics Time: I Will Bite You! and Other Stories

June 20, 2011I Will Bite You! and Other Stories

Joseph Lambert, writer/artist

Secret Acres, April 2011

128 pages

$14

Buy it from Secret Acres

Buy it from Amazon.com

You want to see artists riding their personal visual vocabulary past the realm of utility and into Idiosyncracy Land. From Kirby crackle and Ditko hands to Jim Woodring’s fungoids and Al Columbia’s erasures, signature tropes are frequently a sign that something not so much practical as alchemical is going on in that artist’s brain when he puts lines on paper. Judging from this splash-making debut book from Joseph Lambert, a collection of work previously published in various anthologies and minicomics, Lambert has several such obsessions: Big grinning suns with devious intentions, fumingly angry and violent little children, and using the perspectivally flattening effect of two-dimensional line art to make people and things interact in unexpected ways — characters grabbing their word balloons to use as weapons, people in the foreground jumping onto objects that in “reality” are miles away or literally in outer space. The problem is that none of these visual tricks say much of anything to me. Watching an angry little kid leap into the air and assault the onlooking sun makes for a clever visual, but not a particularly communicative one. Children’s stories have used this kind of device to convey the naivete of their protagonists, and the matter-of-fact wonders of the world when seen through a child’s eyes; mythology uses it to bring a huge and frightening world down to our level, to grant us a degree of control. For Lambert, I think there’s an exploration of rage and frustration under here someplace, but it’s diluted from overuse. If that many characters are angry enough to threaten the sun, then how angry are any of them, really? It’s as though Lambert held his thumb out and blotted out the sun and thought “Wouldn’t it be neat to draw something that did that literally?” And yes, it’s neat, but after a while it’s not much more than that. Too many of the visuals presented here — word-balloon weapons, dancin’ on the ceiling perspective shifts, characters swallowing other characters whole and unharmed — have that feeling. “Why not?” is a terrific question for an artist to ask himself; “why?” is sometimes a better one.