Posts Tagged ‘Fantagraphics’

The 20 Best Comics of 2011

January 1, 201220. Uncanny X-Force (Rick Remender and Jerome Opeña, Marvel): In a year when the ugliness of the superhero comics business became harder than ever to ignore, it’s fitting that the best superhero comic is about the ugliness of being a superhero. Remender uses the inherent excess of the X-men’s most extreme team to tell a tale of how solving problems through violence in fact solves nothing at all. (It has this in common with most of the best superhero comics of the past decade: Morrison/Quitely/etc. New X-Men, Bendis/Maleev Daredevil, Brubaker/Epting/etc. Captain America, Mignola/Arcudi/Fegredo/Davis Hellboy/BPRD, Kirkman/Walker/Ottley Invincible, Lewis/Leon The Winter Men…) Opeña’s Euro-cosmic art and Dean White’s twilit color palette (the great unifier for fill-in artists on the title) could handle Remender’s apocalyptic continuity mining easily, but it was in silent reflection on the weight of all this death that they were truly uncanny.

19. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 3: Century #2: 1969 (Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill, Top Shelf/Knockabout): I’ll admit I’m somewhat surprised to be listing this here; I’ve always enjoyed this last surviving outpost of Moore’s comics career but never thought I loved it. But in this installment, Moore and O’Neill’s intrepid heroes — who’ve previously overcome Professor Moriarty, Fu Manchu, and the Martian war machine — finally succumb to their own excesses and jealousies in Swinging London, allowing a sneering occult villain to tear them apart with almost casual ease. It’s nasty, ugly, and sad, and it’s sticking with me like Moore’s best work.

18. The comics of Lisa Hanawalt (various publishers): As I put it when I saw her drawing of some kind of tree-dwelling primate wearing a multicolored hat made of three human skulls stacked on top of one another, Lisa Hanawalt has a strange imagination. And it’s a totally unpredictable one, which is what makes her comics – whether they’re reasonably straightforward movie lampoons or the extravagantly bizarre sex comic she contributed to Michael DeForge and Ryan Sands’s Thickness anthology, as dark and damp as the soil in which its earthworm ingénue must live – a highlight of any given day a new one pops up.

17. Daybreak (Brian Ralph, Drawn and Quarterly): Fort Thunder’s single most accessible offspring also proves to be its bleakest, thanks to an extended collected edition that converts a rollicking first-person zombie/post-apocalypse thriller into a troubling meditation on the power of the gaze. Future artcomics takes on this subgenre have a high bar to clear.

16. Habibi (Craig Thompson, Pantheon): It’s undermined by its central characters, who exist mainly as a hanger on which this violent, erotic, conflicted, curious, complex, endlessly inventive coat of many colors is hung. But as a pure riot of creative energy from an artist unafraid to wrestle with his demons even if the demons end up winning in the end, Habibi lives up to its ambitions as a personal epic. You could dive into its shifting sands and come up with something different every time.

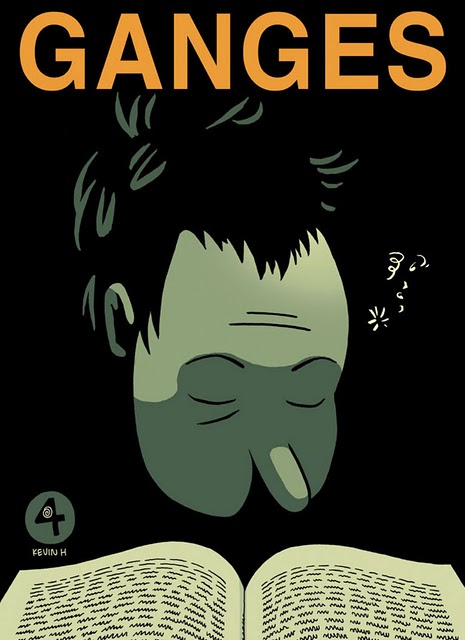

15. Ganges #4 (Kevin Huizenga, Coconino/Fantagraphics): Huizenga wrings a second great book out of his everyman character’s insomnia. It’s quite simple how, really: He makes comics about things you’d never thought comics could be about, by doing things you never thought comics could do to show you them. Best of all, there’s still the sense that his best work is ahead of him, waiting like dawn in the distance.

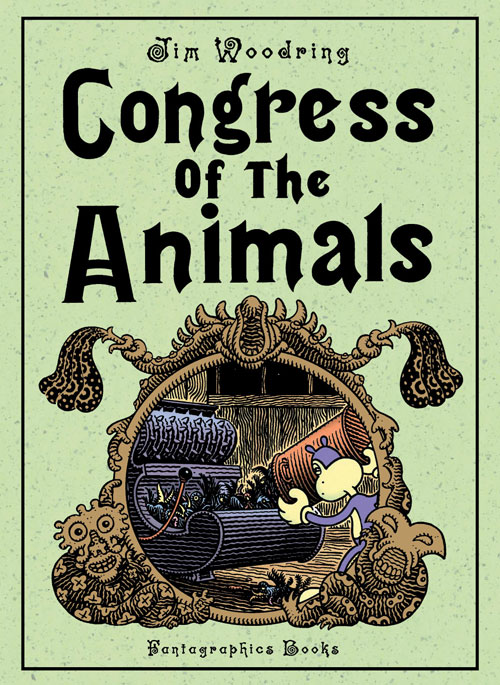

14. The Congress of the Animals (Jim Woodring, Fantagraphics): The potential for change explored by the hapless Manhog in last year’s Weathercraft is actualized by the meandering mischief-maker Frank this time around. While I didn’t quite connect with Frank’s travails as deeply as I did with Manhog’s, the payoff still feels like a weight has been lifted from Woodring’s strange world, while the route he takes to get there is illustrated so beautifully it’s almost superhuman. It’s the happy ending he’s spent most of his career earning.

13. Mister Wonderful (Daniel Clowes, Pantheon): Speaking of happy endings an altcomix luminary has spent most of his career earning! Clowes’s contribution to the late, largely unlamented Funny Pages section of The New York Times Magazine is briefly expanded and thoroughly improved in this collected edition. Clowes reformats the broadsheet pages into landscape strips, eases off the punchlines and cliffhangers, blows individual images up to heretofore unseen scales, and walks us through a self-sabotaging doofus’s shitty night into a brighter tomorrow.

12. The comics of Gabrielle Bell (various publishers): Bell is mastering the autobiography genre; her deadpan character designs and body language make everything she says so easy to buy – not that that would be a challenge with comics as insightful as her journey into nerd culture’s beating heart, San Diego Diary, just by way of a for instance. But she’s also reinventing the autobiography genre, by sliding seamlessly into fictionalized distortions of it; her black-strewn images give a somber, thoughtful weight to any flight of fancy she throws at us. What a performance, all year long.

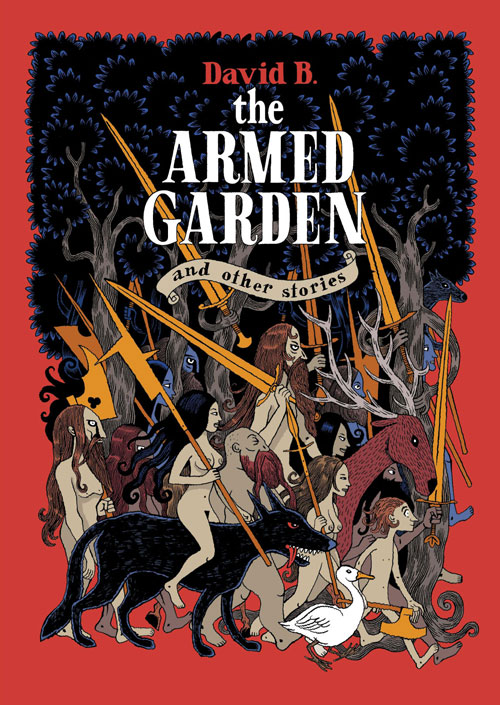

11. The Armed Garden and Other Stories (David B., Fantagraphics): Religious fundamentalism is a dreary, oppressive constant in its ability to bend sexuality to mania and hammer lives into weapons devoted to killing. But it has worn a thousand faces in a millennia-long carnevale procession of war and weirdness, and David B. paints portraits of three of its masks with bloody brilliance. Focusing on long-forgotten heresies and treating the most outlandish legends about them as fact, B.’s high-contrast linework sets them all alight with their own incandescent madness.

10. Too Dark to See (Julia Gfrörer, Thuban Press): It was a dark year for comics, at least for the comics that moved me the most. And no one harnessed that darkness to relatable, emotional effect better than Julia Gfrörer. Her very contemporary take on the legend of the succubus was frank and explicit in its treatment of sexuality, rigorously well-observed in its cataloguing of the spirit-sapping modern-day indignities that can feed depression and destroy relationships, and delicately, almost tenderly drawn. It’s like she held her finger to the air, sensed all the things that can make life rotten, and cast them onto the pages. She made something quite beautiful out of all that ugly.

9. The comics and pixel art of Uno Moralez (self-published on the web at unomoralez.com): What if an 8-bit NES cut-scene could kill? The digital artwork of Uno Moralez — some of it standard illustrations, some of it animated gifs, some of it full-fledged comics — shares its aesthetic with The Ring‘s videotape or Al Columbia’s Pim & Francie: a horror so cosmically black, images so unbearably wrong, that they appear to have leaked into and corrupted their very medium of transmission. Moralez fuses crosses the streams of supernatural trash from a variety of cultures — the legends and Soviet art of his native Russia, the horror and porn manga of Japan, the B-movies and horror stories of the States, the formless sensation aesthetic of the Internet itself — into a series of images that is impossible to predict in its weirdness but totally unflagging in its sense that you’d be better off if you’d never laid eyes on it. I can’t wait to see more.

8. The comics of Michael DeForge (various publishers): The last time you saw a cartoonist this good and this unique this young, you were probably reading the UT Austin student newspaper comics section and stumbling across a guy named Chris Ware. All four of DeForge’s best-ever comics — his divorced dad story in Lose #3, his shape-shifting/gender-bending erotica in Thickness #2, his self-published art-world fantasia Open Country, and his gorgeously colored body-horror webcomic Ant Comic — came out this year, none of them looking anything at all like anything you could picture before seeing your first Michael DeForge comic. It’s almost frightening to think where he’ll be five years from now, ten years from now…or even just this time next year.

7. The comics and art of Jonny Negron (various publishers): What if someone took Christina Hendricks’s walk across the parking lot and trip to the bathroom in Drive and made an entire comics career out of them? That is an enormously facile and reductive way to describe the disturbing, stylish, sexy, singular work of Jonny Negron, the breakout cartoonist of the year, but it at least points you in the right direction. No one’s ever thought to combine his muscular yet curiously dispassionate bullet-time approach to action and violence, his Yokoyama-esque spatial geometry, his attention to retrofuturistic fashion and style, his obvious love of the female body in all its shapes and sizes, and his ambient Lynchian terror; even if they had, it’d be tough to conceive of anyone building up his remarkable body of work in such a short period of time. Open up your Tumblr dashboard or crack an anthology (Thickness, Mould Map, Study Group, Smoke Signal, Negron and Jesse Balmer’s own Chameleon), and chances are good that Negron was the weirdest, best, most coldly beautiful thing in it. It’s like a raw, pure transmission from a fascinating brain.

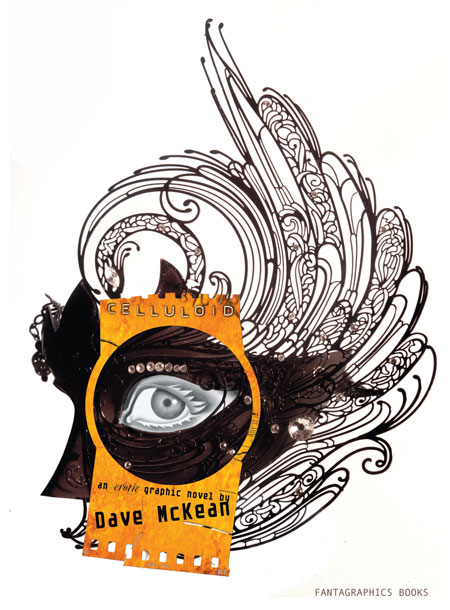

6. The Wolf (Tom Neely, I Will Destroy You): Neely’s wordless, painted, at-times pornographic graphic novel feels like the successful final draft to various other prestigious projects’ false starts. It’s a far less didactic, more genuinely erotic attempt at high-art smut than Dave McKean’s Celluloid; a less self-conscious, more direct attempt at frankly depicting both the destructive and creative effects of sex on a relationship via symbolism than Craig Thompson’s Habibi; a blend of sex and horror and narrative and visual poetry and ugly shit and a happy ending that succeeds in each of these things where many comics choose to focus on only one or two.

5. The Cardboard Valise (Ben Katchor, Pantheon): Prep your time capsules, folks: You’d be hard pressed to find an artifact that better conveys our national predicament than Ben Katchor’s latest comic-strip collection, a series of intertwined vignettes created largely before the Great Recession and our political class’s utter failure to adequately address it, but which nonetheless appears to anticipate it. Its message — that blind nationalism is the prestige of the magic trick used by hucksters to financially and culturally ruin societies for their own profit — is delightfully easy to miss amid Katchor’s remarkable depictions of lost fads, trends, jobs, tourist attractions, and other detritus of the dying American Century. He’s the very most funnest Cassandra around.

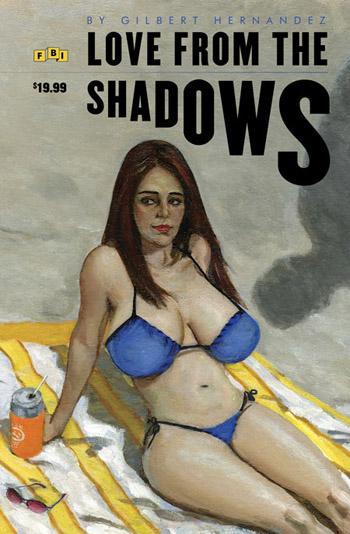

4. Love from the Shadows (Gilbert Hernandez, Fantagraphics): I picture Gilbert Hernandez approaching his drawing board these days like Lawrence of Arabia approaching a Turkish convoy: “NO PRISONERS! NO PRISONERS!” In a year suffused with comics funneling pitch-black darkness through a combination of sex and horror, none were blacker, sexier, or more horrific than this gender-bending exploitation flick from Beto’s “Fritz-verse.” None also functioned as a rejection of the work that made its creator famous like this one did, either. Not a crowd-pleaser like his brother, but every bit as brilliant, every bit as fearless.

3. Garden (Yuichi Yokoyama, PictureBox): Like a theme park ride in comics form — with the strange events it chronicles themselves resembling a theme park ride — Yokoyama’s book is a breathtaking, breathless experience. Alongside his anonymous but extravagantly costumed non-characters, we simply go along for the ride, exploring Yokoyama’s prodigious, mysterious imagination as he concocts a seemingly endless stream of increasingly strange interfaces between man and machine, nature and artifice. As a metaphor for our increasingly out-of-control modern life it’s tough to top. As pure thrilling kinetic cartooning it’s equally tough to top.

2. Big Questions (Anders Nilsen, Drawn & Quarterly): Last year, I wrote that if the collected edition of Nilsen’s long-running parable of philosophically minded birds and the plane crash that turns their lives upside-down didn’t top my list whenever it came out, it must have been some kind of miracle year. Turns out that it was. But you’d pretty much have to create a flawless capstone to a thirty-year storyline of neer-peerless intelligence and artistry to top this colossal achievement. Nilsen’s painstaking, pointillist cartooning and ruthless examination of just how little regard the workings of the world have for any given life, human or otherwise, marks him as the best comics artist of his generation, and solidifies Big Questions‘ claim as the finest “funny animal” comic since Maus.

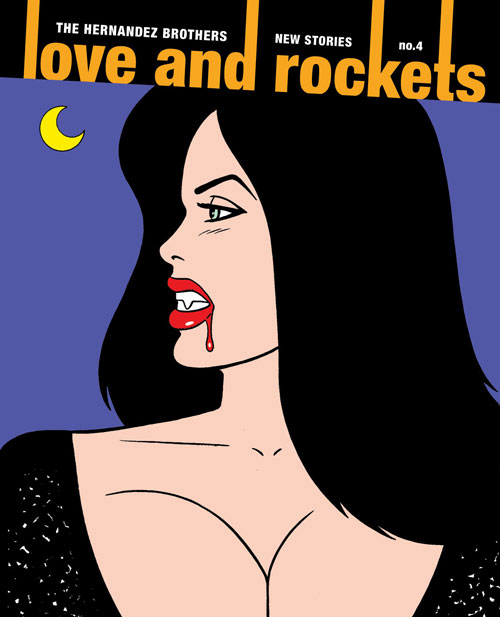

1. Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 (Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, Fantagraphics): Gilbert got his due elsewhere on my list, so let’s ignore his contribution to this issue, which advance the saga of his bosomy, frequently abused protagonist Fritz Martinez both on and off the sleazy silver screen. Instead, let’s add to the chorus praising Jaime’s “The Love Bunglers” as one of the greatest comics of all time, the point toward which one of the greatest comics series of all time has been hurtling for thirty years. In a single two-page spread Jaime nearly crushes both his lovable, walking-disaster main characters Maggie and Ray with the accumulated weight of all their decades of life, before emerging from beneath it like Spider-Man pushing up from out of that Ditko machinery. You can count the number of cartoonists able to wed style to substance, form to function, this seamlessly on one hand with fingers to spare. A masterpiece.

Comics Time: The Armed Garden and Other Stories

December 23, 2011The Armed Garden and Other Stories

David B., writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2011

112 pages, hardcover

$19.99

Read a 10-page preview and buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

About the only things impeding my completely unfettered enjoyment of and admiration for everything David B. achieves in The Armed Garden and Other Stories are familiarity — all three of the stories collected here appeared in the late, lamented Mome anthology at some point; and, because I am a morose and unpleasant person, the happy-ish ending — after a book of unremitting, near-ecstatic horror and slaughter, ending on a wistful up-note felt not so much unearned as simply unwanted.

But that’s it. Other than that, this collection is absolutely marvelous, a gorgeous and searing series of comics from an artist who earns the description “freakishly talented” as completely as anyone this side of his trans-Atlantic fellow in crafting dreamy/nightmarish parables of violent spirituality, Jim Woodring. These comics are just as lovely and just as frightening, and just as singularly the work of their creator and no other.

For one thing, they’re beyond gorgeous. B. has developed a form of expressionism that relies on curves rather than angles; simultaneously he’s fleshed out the stark intensity of his high-contrast black-and-white brush art with a lush duotone gold. The result is battle scenes that have the sharpness and savagery of a woodcut and the graphic simplicity of a Dark Ages tapestry, tied to prophetic visions and hedonistic reveries among the faithful peopled by characters you want to reach out and hug, so sensuous and inviting they seem. It’s almost unfair that the same guy who’s developed a visual language for battle that eloquently reduces its participants to interlocking graphic elements, a nigh-undifferentiated sea of swords, spears, grimaces, and gouts of blood, also maybe draws the sexiest pale naked women I’ve ever seen in a comic. But from a thematic perspective these stories are all about the way that religious fervor lends an air of all-consuming certainty and nobility to mankind’s most animalistic pursuits, from fucking to killing, so I suppose it’s only fitting.

Each of The Armed Garden‘s three stories — “The Veiled Prophet,” the title tale, and “The Drum Who Fell in Love” — is a transmission from the heightened reality of the legends surrounding various medieval religious cults, one from Arab Islam and two warring ones from European Christianity. As I mentioned when the first of these, “The Veiled Prophet,” hit our shores in Mome, they at first appear to all the world like an expressionistically drawn work of historical fiction, until the supernatural elements slowly take over. By focusing on the individual actors in each drama rather than the overall sweep of the history surrounding them, B. allows the reader to experience the awe and terror of divine/demonic intervention as a first-hand phenomenon; within the world of the stories, it’s as easy to swallow as are the more run of the mill sources of conflict with rival Popes and caliphs and so on. We get swept up in the madness and terror along with everyone else. And in all three cases, the fire of divinity burns too bright, consuming those who fan its flames. Provided you don’t buy its actual intervention in actual real life — and by situating each story within rejected, discredited cults, B. effectively removes the need to consider the more popular and lasting religions in this light — the message is clear: Belief in this shit, actualized into violence, will drive you as crazy and destroy you as completely as the real deal will. Gazing beneath the veil of the prophet, building your own paradise on earth, peering into the secrets of creation, communing with the dead, slaughtering out a path for God to tread — these things will kill you, blind you, drive you insane, leave you stranded with only the music of your mind for company. Ugly truths, presented as beautifully as is humanly possible.

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 22: Fall 2011

December 20, 2011Mome Vol. 22: Fall 2011

Zak Sally, Kurt Wolfgang, Jordan Crane, Chuck Forsman, Steven Weissman, Sara Edward-Corbett, Laura Park, Tom Kaczynski, Joe Kimball, Jesse Moynihan, Josh Simmons, The Partridge in the Pear Tree, Malachi Ward, Eleanor Davis, James Romberger, Derek Van Gieson, Michael Jada, Tim Lane, Nate Neal, Wendy Chin, Anders Nilsen, Tim Hensley, Lilli Carré, T. Edward Bak, Nick Drnaso, Joseph Lambert, Paul Hornschemeier, Sergio Ponchione, Nick Thorburn, Dash Shaw, Ted Stearn, Jim Rugg, Victor Kerlow, Noah Van Sciver, Gabrielle Bell, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds, editor

Fantagraphics, 2011

240 pages

$19.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

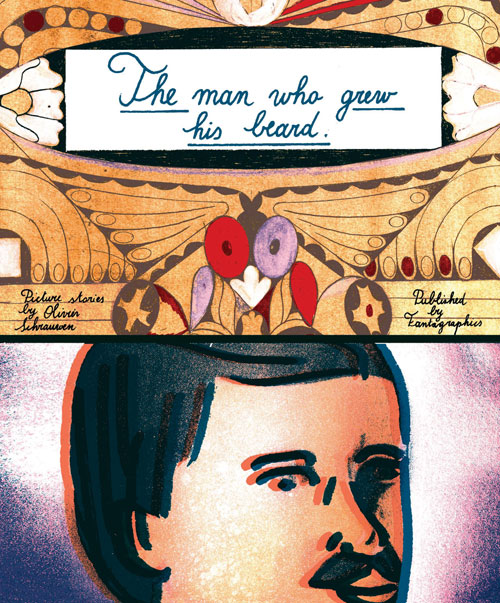

Comics Time: The Man Who Grew His Beard

December 19, 2011The Man Who Grew His Beard

Olivier Schrauwen, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2011

112 pages

$19.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

I love the disconnect between how big and broad this substantial softcover feels in your hands — at 8.5″ x 10.25 ” it’s just wider enough than your average graphic novel for you to notice it — and how tiny the little mustachioed men who people most of its stories feel on those big pages, even when they’re blown up big enough to occupy most of that real estate. It makes it feel even more alien than it already does, like you’re reading a giant’s minicomic.

I don’t know how he does it, whether it’s something to do with how he puts his lines down on paper or some treatment he gives them afterwards, but Flemish cartoonist Olivier Schrauwen makes images that look like…like they’ve been transmitted from a great distance, both temporally and spatially. He’s playing with style and design that looks like it predates the Great War, and his line and coloring has a hazy feel to it that could be a copy of a copy of a copy, or the unlikely discovery of some microscopic cartooning culture blown up to many times its original size. There’s something off about it just as surely as there’s something off about Al Columbia’s rotted vintage visuals, only here that off-ness is used in service of a comic surrealism rather than a horrific one. He can stick it to the foibles of the 19th-century culture whose style he’s swiping quite effectively — savagely satirizing Belgium’s bloody misadventures in Africa, parodying the West’s penchant for physiognometric pseudoscience with a look at what your hairstyle says about your mental capacity, lampooning the world-conquering bravado of transcontinental rail, and so on. But he’s just as likely to seize upon some strange effect or idea and run with it as hard and as fast as he can — nearly literally, in once case, in a strip consisting more or less solely of a guy running to catch a train for as long and as far as the train would have taken him to begin with. Elsewhere, he shatters sexual idylls into a fractal feedback loop or draws its participants as lounging subjects of some kind of weird cubist stained-glass art style; portrays a man who can paint things into existence by trotting him through a series of guffaw-inducing mock-heroic poses, as if his miraculous creative abilities were only secondary proof of his awesomeness compared to his theatrical, bare-chested machismo; and uses bright color and titanically ornate architecture against bland ones to paint a portrait of a catatonic man’s rich and adventurous interior life of fun with a beautiful woman and a beloved child, in a story that ended up being actually quite moving. These are deeply strange short stories, centered on ideas and effects I’m not sure I’d have come up with even with the proverbial infinite number of monkeys at my disposal; even in this short-story-saturated alternative comics climate, there’s nothing else like his gestalt of finely calibrated nonsense. It’s good to see that comics can do things you’d never think to ask of them in the first place.

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 21: Winter 2011

December 16, 2011Mome Vol. 21: Winter 2011

Sergio Ponchione, The Partridge in the Pear Tree, Josh Simmons, Dash Shaw, Steven Weissman, Kurt Wolfgang, Sara Edward-Corbett, Nicolas Mahler, Tom Kaczynski,

Josh Simmons, Jon Adams, Nate Neal, T. Edward Bak, Michael Jada, Derek Van Gieson, Nick Thorburn, Lilli Carré, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds, editor

Fantagraphics, 2011

112 pages

$14.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

It was the best of Momes, it was the worst of Momes. Alright, that’s not quite accurate, and not quite fair, either. But this unwittingly penultimate issue of Fantagraphics’ long-running alternative-comics anthology — page for page the longest-running such enterprise in American history! — is a hit-or-miss affair in the mighty Mome manner. In the miss column you can place Sergio Ponchione’s bombastic, cartoony fantasy about an imaginary childhood friend brought to life; there’s really not much more to it than that description would indicate. Ditto Kurt Wolfgang’s next “Nothing Eve” chapter, which continues to work the “people still act pretty much the same even though the end of the world is coming” buttons it’s been mashing since issue #1. T. Edward Bak’s “Wild Man” remains awkwardly paced due to its split-up narrative captions; Nicolas Mahler’s autobio strip remains of limited interest to people not Nicolas Mahler; Lilli Carré’s contribution is nicely colored in reds and blues but otherwise insubstantial.

A few contributions are both hit and miss at once. Sara Edward-Corbett’s near-wordless reverie involving inanimate objects romping around the outside of a house comes across more inscrutable than mysterious, but at the same time her crosshatching and linework are an absolute marvel, and she’s playing with forms (and with form) in a fashion reminiscent of John Hankiewicz, if not as successful. Steven Weissman’s deadpan “Barack Hussein Obama” strips fall flat when they merely parody the rhythms of four-panel gag comics, but spring to surreal and oddly scathing life when he injects a healthy dose of the sinister supernatural into them. I’ve never quite cottoned to the way Jon Adams’s razor-thin line and labored-over character renderings sit against the large white expanses of his pages, and his writing feels overwrought to me, but he does give his blackly humorous tale of a hunting expedition gone bad a laugh-out-loud visual punchline. And Nate Neal’s caveman morality play makes much better use of his meaty cartooning than his lukewarm slice-of-lifers do, though the conceit of gibberish dialogue from the cavepeople conceals more than it illuminates.

So that leaves the hits, and they’re strong enough to make the book worth checking out. Dash Shaw continues his seemingly ongoing series of adaptations of “reality” programming, this time an excerpt from a making-of documentary about Jurassic Park; he has a really sharp and off-kilter eye for people observing and commenting on their own behavior for a camera, and his transition from talking heads to full documentary “footage” is a gleeful one. Nick Thorburn’s take on Benjamin Franklin, a first-person monologue in which Ben lets us in on a dirty little secret, is anachronistically absurd (“In Seventeen-Sumthin’-Er-Other, right before I invented electricity and just after I’d sired my illegitimate son, I received an e-mail from Lord Sandwich about comin’ to London to take part in this new secret society known as ‘The Hellfire Club.'”) and very funny, with a great undergroundy character design for Franklin himself. Derek Van Gieson’s murky World War II period piece continues to stun from page to page. Tom Kaczynski examines home ownership during terminal-stage capitalism as only he can, casting it as a catalyst for powerful erotic and apocalyptic impulses and proving himself once again to be one of the most stealthily sexy cartoonists working today. “Stealthy” isn’t a word I’d use for Josh Simmons, but he doesn’t need it: His weird psychedelic fantasia on racism “The White Rhinoceros” is as bold and bulldozing as the giant slugs who stampede across its pages, and the elliptically concluded short story “Mutant” ends with an image of an enraged creature in the form of a human female, her nude body shadowed but covered in glistening sweat, that may as well symbolize the workings of Simmons’s entire brain. You gotta take the rough to find the diamonds.

Comics Time: Like a Sniper Lining Up His Shot

December 15, 2011Like a Sniper Lining Up His Shot

Jacques Tardi, writer/artist

Adapted from the novel by Jean-Patrick Manchette

Fantagraphics, 2011

104 pages, hardcover

$18.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

Fantagraphics keeps churning out lovely translated editions of the work of French comics master Jacques Tardi at a truly admirable clip. This is the fourth in what I would consider the “main” Tardi/Fanta line of slim hardcovers, distinguished by no-nonsense Adam Grano cover designs that juxtapose key sequences from Tardi’s ink-soaked black-and-white interior art with bold slashes of color and block-caps for title and credit information. If there’s a better mesh of form and function in comics right now this side of, well, Fanta’s similarly designed Love and Rockets digests, I’d sure love to see it. In much the same vein as Tardi’s previously released adaptation of a crime novel by author Jean-Patrick Manchette, West Coast Blues, Like a Sniper Lining Up His Shot is a grimly economical story of a man on the run from killers, with bursts of violence that slash in out of nowhere. In other words, you can judge a book by its cover.

The two books have much in common beyond their common language of men hunted by hitmen across the length and breadth of France. Both protagonists are bizarrely taciturn about their predicaments, almost to the point where you’re left to wonder if there’s some sort of mental disability involved. Sniper‘s Martin Terrier (great name) at least has the excuse of being a mercenary and assassin to explain his flat affect where killing’s concerned, as opposed to West Coast Blues‘ wrong-man family-guy George. But he more than makes up for this in his personal life, a disaster area predicated entirely on his deeply weird belief that the women with whom he involves himself can switch their affections for him on and off after years of one setting or the other based solely on his say-so. The woman for whom he “risks it all” — Tardi and Manchette’s interpretation of this trope ladles those sneer quotes all over it — is an equally weird and unpleasant character, ricocheting from emotion to emotion when Terrier’s intrusion into the life she’d been leading without him violently upends her status quo, until finally settling on some weird sneering sex-hungry brand of derision for him and his life of crime and adventure.

In all honesty, these emotional and behavioral patterns are so difficult to recognize even when allowing for the remove between a hired gun and a comics critic that they get in the way of Tardi and Manchette’s underlying indictment of society’s casual savagery, and its propensity for covering up that savagery with bullshit that pins it on The Other Side. But upon reflection, I wonder if these terrible people’s wholly alien way of interacting with the world isn’t just the writing equivalent of Tardi’s nimble, scribbled line and sooty blacks — a heightened reality in which things are rendered at their loosest, darkest, ugliest, and weirdest at all times. God knows both creators can rigorously focus when they want: Manchette squeezes a quite believable custody battle between Terrier and his now-ex girlfriend over a beloved cat into the proceedings, while Tardi’s backgrounds and lighting effects are a realist’s dream and his action sequences and set-pieces are choreographed tighter than a drum. The absurdist demeanors may prevent everything from gelling as well as they might have done, but overall the book delivers a fastball to your face so hard that you barely have time to notice that some of the stitches need straightening.

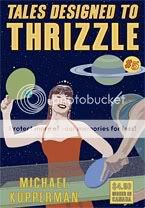

Comics Time: Tales Designed to Thrizzle #7

November 23, 2011Tales Designed to Thrizzle

Michael Kupperman, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, November 2011

32 pages

$4.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

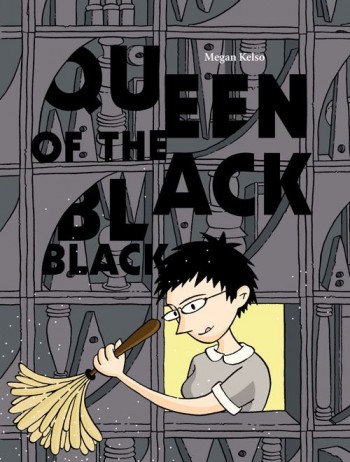

Comics Time: Queen of the Black Black

November 14, 2011Queen of the Black Black

Megan Kelso, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2011

168 pages

$19.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: Ganges #4

October 21, 2011Ganges #4

Kevin Huizenga, writer/artist

Fantagraphics/Coconino Press, October 2011

32 pages

$7.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

He’s your worst nightmare

October 20, 2011Comics Time: Love from the Shadows

October 5, 2011Love from the Shadows

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2011

120 pages, hardcover

$19.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For reasons unknown to me, I did not create a Comics Time entry for this review, which was posted on April 20 at The Comics Journal. I’m just rectifying the situation now. Please visit TCJ.com for the review.

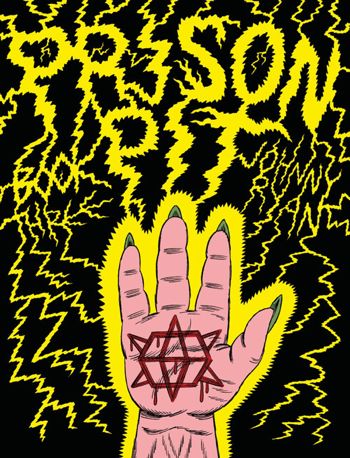

Comics Time: Prison Pit: Book Three

September 28, 2011Prison Pit: Book Three

Johnny Ryan, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, September 2011

120 pages

$12.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: Tales Designed to Thrizzle #5

August 16, 2011 Tales Designed to Thrizzle #5

Tales Designed to Thrizzle #5

Michael Kupperman, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2009

32 pages

$4.50

Buy it from Fantagraphics

(Originally posted at this blog’s previous location on May 26, 2009; I am reposting it because it does not seem to have made the move to the current site.)

By now I’ve written about how Kupperman’s humor works at some length, so you’d think it would have occurred to me by now that his humor is an entirely different animal from the vast majority of humor comics. Which it is, insofar as it’s funny and most humor comics aren’t. But it wasn’t until this (ironically) prose-heavy issue that I realized he’s not doing gag comics at all. The only four-panel punchline-driven strip in this entire book, “Ever-Approaching Grandpa,” basically exists to give lie to the notion of the four-panel punchline-driven strip (and is own title). He’s not content with using just the words and the visuals. I think what Kupperman’s doing–with his long, digressive “stories,” with his riffs on old-fashioned comic-book covers, and so on–is using the stuff of comics itself as a locus of the comedy. A grid of panels implies continuity of action, so he uses that to present an increasingly bizarre and disjointed Twain & Einstein adventure with barely any internal cohesion whatsoever. We assume that captions or word balloons will comment on the visuals against which they are juxtaposed, so he creates a how-to arts-and-crafts strip that for no apparent reason is also a brutal noir (“How to Pattern Print with a Potato, Johnny”). We’ve come to accept certain visual cues as meaning a certain thing, so he literalizes them so that they mean something entirely different–a phone in the extreme foreground actually turns out to be a just-plain gigantic phone; a mother’s wagging finger radiates motion lines that turn out to be “super-vibrations.” In his way, Kupperman’s just as concerned with making comics’ formal aspects work for him as Chris Ware. In his way he’s every bit as effective. Goddammit this book is funny.

Comics Time: Love and Rockets: New Stories #4

August 1, 2011Love and Rockets: New Stories #4

Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, writers/artists

Fantagraphics, August 2011

104 pages

$14.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 will turn any fan of Los Bros Hernandez into the host of The Chris Farley Show. “Remember? That time? When you drew Calvin’s plaid shirt? So that the plaid was always facing in the same direction? No matter how much Calvin moved?…That was awesome.” I am seriously finding it difficult, if not impossible, to review this comic without simply hitting the bullets-and-numbering button and whipping up a list of everything in it that amazed me. It would be a long list, too. But I’m abstaining as much as I can — to challenge myself for starters, and to avoid spoiling the comic for those of you who haven’t yet read it (which is probably most of you since it’s not out yet) for the most part. But I’m also holding off on that listicle because I think it’s a cheat. The fact of the matter is that while reading this book I discovered that I’m at least as attached to Ray Dominguez and Fritz Martinez, the protagonists of Jaime and Gilbert’s contributions respectively, as I am to a decent number of real people in my life. So sure, I could rattle off the ways in which Xaime and Beto continually prove themselves to be among the most graphically inventive and entertaining cartoonists alive some three decades into their careers — the crosshatching on Ray’s shirt and Maggie’s sofa; Gilbert’s use of wavy, puddle-shaped, impenetrable fields of black in his vampire story; the impact of the just-this-side-of-parallel lines of Angel’s body as she bends her leg to put on a high heel; the upside-down lava-lamp shape of Fritz’s legs in a skirt, used as an anchor for panel after panel of her simply walking around town with her agent ex; dredging up a long-ago, possibly long-forgotten character, drawing him as a late-middle-aged man in a way that makes him unrecognizable until you realize just how recognizable he is; the smashed-skull-as-cubist-masterpiece in Gilbert’s customary burst of horrifying ultraviolence; the holy shit moment when you realize the visual structure to that montage spread from Jaime’s story; Gilbert storming the ramparts of the vampire story and launching sex and violence back into it like payloads from a trebuchet; Jaime serving up a story whose snapshot style echoes comparable material from “Wigwam Bam” in significant and story-relevant ways; tracing the similarities and differences between Killer and Fritz via the characters they play, the use of their amazing bodies fraught with story information. And hey, look at that, I did rattle them off! But in the end, how it looks pales in insignificance next to what happens, because making it look that good is a means to the end of imparting just how much what happens matters. Ray’s shirt and Fritz’s legs, the shadow of the vampire and the structure of the montage — they’re just landmarks to remind you where you were when you found out if Ray and Fritz and Maggie were going to get happy endings, or not. It’s the easiest thing in the world to understand, and it’s the hardest thing in the world to do, and it’s magic, pure magic, to do it this well.

Comics Time: Congress of the Animals

July 27, 2011Congress of the Animals

Jim Woodring, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, June 2011

104 pages, hardcover

$19.99

Buy it and read a preview at Fantagraphics.com

Perhaps I should have seen it coming after the palpable (if fleeting) triumph of good over evil that comprised the climax of Weathercraft, Jim Woodring’s previous standalone graphic novel set in the world of his funny-animal avatar Frank. Regardless, I’ll admit it: I did not expect to read a Frank book whose final panel made me go “Awwww!”

It’s true that in Weathercraft, Frank’s hapless antagonist Manhog achieves enlightenment that for a short while allows him to become an elemental force of kindness, justice, and the security of a fundamentally benevolent order to the universe. But it’s only for a short while — the equilibrium restores itself, and he, the insouciant Frank, and the jauntily predatory Whim go back to their old ways. According to Woodring’s typically dense and hilarious jacket copy, we have the Unifactor, the familiar world of bulbous buildings and shoggoth-like plant deities in which Frank and his cohorts dwell, to thank for this state of affairs. Woodring calls the Unifactor “the closed system of moral algebra into which Frank was born, where “in the end, nothing really changes,” and where “Frank is kept in a state of total ineducability by the unseen forces which control that haunted realm.”

The difference here — and I’m not 100% convinced this would have been clear if Woodring hadn’t said so straight out on the jacket, but be that as it may — is that this time around, Frank leaves the Unifactor. Woodring’s customary Rube Goldbergian plot contrivances force Frank into a state of indentured servitude that ends with him on the lam. The journey positions Frank in the midst of various grown-up concerns, such as home ownership, property loss, commerce, employment, amusement, leisure, sex (in the form of what appears to be an angelic anthropomorphic vagina guarded by the giant disembodied head of a Dr. Seuss character), and religion (in the form of nude, beefy men with gaping chasms where their faces are supposed to be, whose ability to expose their guts at will and induce others to do so literally knocks poor Frank out with its disgustingness and is perhaps Woodring’s most troubling sequence since Manhog flayed his own leg); in other words, it’s a bit like Pippin. Normally we’d expect nothing to come of all this, save for an opportunity to marvel at Woodring’s buzzy, vibrating line, proficiency with creature design, and ability to distill unpleasant shit into slightly sinister slapstick adventures for his dog-cat-bear-mouse-thing hero. But the journey takes Frank so far afield that at some point (probably when he gets lost at sea and washes up on some distant shore) he ends up outside the Unifactor’s confines. New information can now enter his world, in the form of a female Frank-like character who lives in a house shaped like Frank. And at that point all hell breaks loose…which in a Frank comic is to say it doesn’t break loose at all.

Somehow, Frank has gained the ability to interact with another being without immediately sizing up the best way to have fun with, or at the expense of, that being, consequences be damned. They chat. They laugh at the bullying creatures who attacked him earlier, and blush at both having got such a kick out of it. (See, he hasn’t been brushed totally clean of his sins — as we see here and elsewhere, both he and his new pal still have a bit of an empathy deficit.) She protects him from the siren song of that angelic vagina-thing. She helps him return home, to the delight of his pets Pupshaw and Pushpaw, who seem overjoyed to find that their master has found his other half. But what really moved me is their simple physical interaction: They hug. I’m “awwww!”ing just thinking about it. That physical act is an act of grace on Woodring’s part, an escape from the mere hedonism or fight-or-flight responses that have been the sole custom of Frank’s world before now. It’s a new, rewarding emotion, embodied. And despite the break it marks from the world of Frank as we knew it, it fits, since isn’t embodying emotion what Frank stories have always been all about?

Comics Time: Celluloid

July 20, 2011Celluloid

Dave McKean, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, June 2011

282 pages, hardcover

$35

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

From a reviewer’s perspective, the nice thing about erotica is that, as with humor, there’s a clear threshold of physical response a work must cross to be judged successful. With humor comics, the key question (there are others, but this is the sina qua non) is “Did it make me laugh?” With erotic comics, it’s…well, let’s just say it ain’t laughter we’re after. And on that basic measurable (ahem) level, Celluloid comes up short (ahem ahem). McKean’s art is as otherworldly as ever, bathed in luminous gold, and until the final section it manages to avoid the “Hey, wanna watch some Sandman covers fuck?” photo gimmickry I was afraid of. But isn’t it kind of odd that of all the palettes McKean could choose to convey the film-projection-as-mystical-sexual-gateway metaphor that is at the heart of our nameless, speechless female protagonist’s “strange erotic journey” (to coin a phrase), he chose gold? Is that what you think of when you think of the shaft of light beaming from the projection booth to the screen, or the light the screen bathes you in in turn? Maybe if you’re Gordon Willis, but not if you’re me. The book is filled with weird little just-off details like that, from our young-ish heroine’s weirdly craggy body and her nose that seems to grow to Cyrano proportions at random depending on the angle McKean’s drawing her at, to the deeply unsexy choice to make our heroine’s foil in a lesbian sequence wear a garland of grapes that’s echoed by her (count ’em) fourteen breasts, leaving me to wonder if one of them was gonna get plucked off and eaten throughout their tryst. Working mostly with full splash pages and spreads, McKean is able to pull off striking isolated images here and there — off the top of my head I remember our heroine’s shocked face as she discovers a plaza full of copulating couples, a dramatic first kiss between our heroine and the grape goddess staged at a scale that makes it look like the sky is tenderly kissing the earth, and (one of the few actually hot moments in the book) her (non-sexual) removal of her top to take a bath right near the beginning of the book. But with the exception of the stunning black, white, and red sequence in which the protagonist sucks a demon’s totemic red dick until it ejaculates milky semen through the void like a spaceship floating by in 2001, isolated images are all they are. They get lost in a melange of homages to Picasso, Ernst, and “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans”-era Dalí, combined with McKean’s usual soft-focus multimedia wizardry and angular cartooning. What’s more, the whole affair has a didactic feel to it, as “let’s prove a point about the artistic legitimacy of erotica”-type comics often do. We’re clearly supposed to be proud of the protagonist’s journey of self-discovery, but all we have to go on to know such a journey is even required is a quick phone call at the beginning with her boyfriend — it’s an unhappy-seeming call, sure, but the impression it gives is that they’ve simply had a rough day at work, not that there’s some sexual void in their shared life that she’s filling in on her own, and certainly not to the point where the events of her magical journey into the sexy celluloid world make sense as a gauntlet to be thrown before the dude, as they are at the book’s end. That final sequence begins when the boyfriend returns home and turns on the mysterious projector that kicked off the woman’s journey. But by the time I closed the book, unfortunately, that projector was the only thing turned on. And that’s the heart, and other organs, of the matter, isn’t it?

Comics Time: Uptight #4

January 28, 2011Uptight #4

Jordan Crane, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, December 2010

36 pages

$3.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

It’s the details that distinguish what Jordan Crane does. He’s not breaking any conceptual or thematic or formal ground in the two stories comprising this fourth issue of his old-school solo-anthology alternative-comic-book series, both of which are continuations of previous stories: “Trash Night” picks up the misadventures of a working-class couple whose female half is conducting a secret affair, while “Dark Day” is another chapter in the saga of Simon and Jack, the school-hating kid and his giant cat who starred in Crane’s all-ages graphic novel The Clouds Above. The latter story is part of your basic “kid explores a magical world beyond the watchful eyes of adults” set-up, while the former presents love and sex through a sordid, hate-fucky lens, an approach I’ll always associate with the 1990s filmography of Jeremy Irons. But none of that accounts for the sticky, unexpected images he pours into these familiar templates. For “Trash Night,” that means the perversely sensual lifelessness of the wife’s eyes, mouth, and breasts as the husband cradles her dead body in a mordant daydream (a recurring theme for Crane at this point); the memorable specificity of the argument that sends her back into the arms of her lover (vegetable oil!); the out-of-nowhere suddenness and savagery with which he attempts to strip her naked when she returns home; the shadowy, samurai-esque way he holds aloft a rake before bringing it down on the body of a raccoon who bit him; the unexpected and believably unglamorous way their bout of make-up sex begins (with him sitting on the toilet as she puts neosporin on his wound); and even the multiple meanings of the title itself, which could refer not just to the husband’s chores but to his likely self-identification as white trash and to the quality of his experiences during the time period. “Dark Day” is equally cleverly named in that it quietly ties this much frothier all-ages affair to the grim day-in-the-life we just read about, and uses irony to draw our attention to how much lighter this strictly black-and-white strip feels compared to the dingy, depressive graytones of the earlier comic. Here, Crane uses his wispy line as a way to cram visual cacophony into each panel, conveying how seeing an adult-created and administered world in disarray can be frightening to a child — the principal’s office, all books and papers and plaques and diplomas precariously overhanging the principal’s ogre-like frame, is at least as menacing as the shadows and icicles and smoke that Simon and Jack and Rosalyn must navigate and escape. At this stage in his career it’s quite clear how impeccable Crane’s technique is, both as an artist and as a designer; I think it’s equally important to note that what he does with that technique is just as considered and just as well-executed.

Comics Time: FUC* **U, *SS**LE

January 19, 2011 FUC* **U, *SS**LE

FUC* **U, *SS**LE

Johnny Ryan, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2010

pages

$11.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

Take a good look at that cover, if you will, and you’ll see what it is that makes Johnny Ryan’s grossout humor comics so special. Blecky Yuckerella isn’t just emitting bog-standard gag-strip flopsweat and stinkflies as she hangs, she’s also squirting out tiny little drops of urine. That’s the kind of attention to detail and willingness to go the extra mile that took Ryan to the top!

In Ryan’s last Blecky collection (co-Bleck-tion?), the fun came in seeing the pacing economy of the four-panel gag strip used as a vehicle for a completely unconstrained sense of the absurd, a willingness to turn the corner into even weirder and more ridiculous or offensive territory with each new panel. By contrast, the fun of FUC* **U, *SS**LE (aside from the title itself, Ryan’s best since Johnny Ryan’s XXX Scumbag Party) is mostly how straightforward it is: Ryan’s got a punchline in mind, and by god he’ll set it up in those first three panels no matter how idiotic it is. Wine made from stomping pig carcasses (“I call it S’wine!”), Curly Moe and Larry as the Messiah (“It’s Stoogeus Christ!”), diarrhea caused by eating Bigfoot (“the Sasquirtz”), a porno called 69-11 (“It’s like 9-11, only more erotic!” Blecky points out as Flight 11 and the North Tower perform oral sex on one another) — I’d say “you can’t make this shit up,” but you can, or Ryan can at least, and watching him frogmarch his characters through the outlandish scenarios needed to give birth to these you-gotta-be-fucking-kidding-me ideas is Guffaw City. And as I always point out, he’s a fine, fine cartoonist; this idea has more traction in a post-Prison Pit world, I know, but you don’t get to see his buoyant brushwork in those books, while here it’s what sells the childlike glee of everything that’s going on. His thick blacks really vary up the dynamics of each page, too. Unfortunately, this Blecky’s final hurrah, as Ryan has retired the strip. You can certainly see how Prison Pit and Angry Youth Comix afford him a lot more formal leeway, but I’m going to miss the consistently high batting average on display in the Blecky books. I guess it’s like Blecky herself tells Aunt Jiggles: “You can either have a lotta annoying noise and a clean robot pussy, or peace and quiet and nasty robot pussy stench. But you can’t have it both ways!”

Comics Time: A Drunken Dream and Other Stories

January 17, 2011 A Drunken Dream and Other Stories

A Drunken Dream and Other Stories

Moto Hagio, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2010

288 pages

$24.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

I frequently gasped, out loud, at the beauty of this goddamn thing. Pioneering Japanese girls’-comics artist Moto Hagio is not a world a way from the shoujo artists you might have seen elsewhere; theirs is a shared vocabulary of thin, beautiful women and men who look like their emotions could lift them off the ground. But Hagio’s line is just a little bit fuller, her character designs a little more lived-in, the endings of her stories a less likely either to pull punches or hit you full-force with maudlin tragedy. Most of them remind me of Jaime Hernandez, of all people, in that the force of the narrative is toward the protagonists coming to terms — with the damage done by a cruel mother, with the inspiration that arose unexpectedly from a childhood tragedy, with the sudden loss of a friendship through a shared mistake in judgment, with the death of a hated rival, with a necessary but traumatic decision, with the death of a parent. Or not! Some characters die, some characters are never afforded the rapprochement they seek, and one little girl gets zapped into nothingness by the conformist overlords of her suddenly science-fictional home. Either way it’s the visual journey that counts just as much as the destination, a journey in love with lush gray textures and stippled explosions of light, and in one memorable strip an array of red-based colors from horror-movie-blood red to rusty russet to hot pink, and portrayed through luxurious swooping lines that make the characters they depict look like Precious Moments dolls gone sexy. (A good thing, I promise you!) Each story’s big narrative and emotional moments seem to swell within and explode out of these textures and lines, like they’ve actualized the potential energy there all along. I dunno, I’m probably sounding a little ridiculous — my point is simply that this is the kind of book whose impact comes as much from simply soaking in the images as reading them, like great comics ranging from Kirby to Fort Thunder. Editor Matt Thorn, who also provides a lengthy essay on and interview with Hagio, is also the book’s translator, and he does a magnificent job; I can’t tell you what a relief it is to read manga with none of the clumsy, overly literal sentence constructions that frequently plague even the best and most well-intentioned such projects, ironically thwarting the author’s intended effect in the name of fealty. Really, really fantastic lettering, even — how often can you say that about translated manga? Reads like a dream, looks like a dream.

Comic of the Year of the Day: Werewolves of Montpellier

December 21, 2010Every day throughout the month of December, Attentiondeficitdisorderly will spotlight one of the best comics of 2010. Today’s comic is Werewolves of Montpellier by Jason, published by Fantagraphics — to quote an Album of the Year of the Day, everybody knows he’s a motherfuckin’ monster.

You have to be a real expert in Jason-character physiognomy to even be able to tell that the lonely expat main character in Werewolves of Montpellier is sometimes wearing a werewolf mask. After all, the guy’s an anthropomorphized dog at the best of times. In the end, that ends up being the gag. You’re not some uniquely unlovable monster, you’re just a guy with problems, like anyone else…

Click here for a full review and purchasing information.