Posts Tagged ‘criticism’

STC on Street Fight Radio

June 3, 2018I was so happy to speak to Bryan Quinby of the terrific left-wing podcast Street Fight in one of their many, many patreon-only bonus shows! Bryan and I are so sympatico that it’s crazy. We discuss criticism, TV, metal, wrestling, how cool Marilyn Manson and Korn were, you name it, for two hours. Absolutely worth the subscription!

The Boiled Leather Audio Hour Episode 75!

May 25, 2018

Matt Zoller Seitz: A 75th Episode BLAH Salon Spectacular!

Television and film critic Matt Zoller Seitz joins us to help celebrate our 75th episode in style! In this special edition of our BLAH Salon interview series, Sean & Stefan talk to Matt about his upcoming Split Screens Festival, a jam-packed series of screenings and panels featuring many of TV’s best writers and performers; the festival runs from May 30-June 3 in New York City. He also tells us about his background, his overall approach to criticism, how the field has changed, and (of course) how he feels about Game of Thrones. Stay tuned after the interview, too, as Sean & Stefan look back on seven years of podcasting. Here’s to seven more!

Additional links:

Split Screens Festival homepage.

Split Screens Festival tickets.

Matt’s work at Vulture and New York.

Matt’s work at RogerEbert.com.

Our Patreon page at patreon.com/boiledleatheraudiohour.

Our PayPal donation page (also accessible via boiledleather.com).

Taste is not clairvoyance

March 12, 2018Today new interviews came out with both Julian Casablancas (ex The Strokes) and Jack White (ex The White Stripes) in which they said a variety of dopey things. Because of this, half of my twitter timeline took victory laps about how they never liked the Strokes and the White Stripes, that the Strokes and the White Stripes were never good, and so on. It’s a low-grade version of how people fall all over themselves to announce that they always hated the work of the latest man to be exposed as a sexual predator, and it’s just as goofy here as it is there.

I understand the compulsion to seize any available opportunity to advertise your distaste for a passionately disliked artist. Couple that with the catharsis of dunking on people who’ve revealed themselves as fools or creeps under any circumstances and it’s like you’re playing socio-critical tee-ball. But in every case, this unspoken logic behind these comments is that only fools and creeps can make shitty art, and you had the perspicacity to see through the act from the start. It’s a totem wielded against the nerve-wracking uncertainty involved in investing your time and energy and emotions in art, a field in which being a smart person, being a good person, and being a good artist often have little to do with one another.

I’ve disliked a lot of art made by people who turned out to be pretty awful; Louis CK is the most obvious example here. But I also love, and continue to love, a lot of art made by such people as well, though I don’t love the people themselves. I’m sure I’ll be disappointed to learn that other artists I love are awful people in the future. And god knows that any number of artists I both love and hate are doofuses. (One of the “I never liked them anyway!” comments I saw about the Strokes and the White Stripes unfavorably compared them to Britney Spears; I like a lot of her music too, but is the implication here supposed to be that she’s never done or said anything unfortunate or asinine?) I’m hard pressed to think of a single case in which my feelings about their work and the truth about them as people had a connection I sussed out years in advance, and therefore now deserve to crow about publicly. Critics, of all people, should know better.

Two aspects of TV criticism I’ve been thinking about a lot recently

March 2, 20181) Every single piece that any critic has ever written and you or I or anyone else has ever read over the past ten years or so about how TV drama is in trouble has been a complete waste of time to both write and read, since there’s basically never more than a month-long stretch between good-to-great shows being on the air. That concept has eaten up SO many column inches at different periods in time, and it’s NEVER been true.

2) Did any major (full-time / on-staff / national) TV critic support Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primary? Can you name one?

Support for Sanders is an insufficient rubric for leftism, obviously; his mild socialism should be the beginning of the conversation. But I suspect that for most entrenched culture writers – I’m singling out TV because it’s the field with which I’m most familiar but I wouldn’t be surprised if this were true in other areas as well – Sanders and his ideology are as out of bounds as they are for, well, every single op-ed page at every major paper in America, at none of which are Sanders supporters or socialists generally represented.

Anyway, this is an honest question: Are any major TV critics Sanders supporters or self-identified socialists? I can’t think of any, but it’s possible I’m overlooking someone.

(FWIW I can think of two or three non-major ones, myself included. And I can think of a couple who are on the left but have ambivalent, primary campaign–related feelings about Sanders himself. That’s…not a lot.)

If I’m not leaving anyone out, I think we’ve discovered a limit to what you’re going to get out of the field.

Wonderland Episode 107: Tropes and Traps in Culture

November 15, 2017I’m a guest on episode 7 of Wonderland, a new podcast series about popular culture as a potential vehicle for political change. I spoke with hosts Bridgit Antoinette Evans & Tracy Van Slyke and my fellow guest Nayantara Sen about the storytelling pitfalls television falls into, and how climbing out of them is an opportunity to both tell better stories and do better political work within them. The conversation is a lot of fun, and the whole series is up all at once, so if you like what you hear, binge the whole thing!

10 Top TV Critics Share the Difference Between a Good TV Show and a Great One

November 13, 2017Great TV is characterized by the same thing present in all great art: a sense that you’re reading an open text, with parts you can’t pin down but which nevertheless add up to a greater whole. The best shows are all challenging and, for want of a better word, “weird” — that is, there’s stuff going on that a plot summary or a recitation of the dialogue can’t capture. I don’t want to come away feeling comforted, reassured, or satisfied that I’ve solved what I just saw. I don’t want to be let off the hook.

Twitter and anger

November 6, 2017One thing I’ve noticed since I stopped using Twitter regularly is that the compulsion to tweet is most often associated with complaint. I think all of the times I’ve actually broken my self-imposed embargo since it began and tweeted something other than promoting work by me, my friends, or people I admire have been to say something negative. I complained about commenters who don’t understand how criticism works. I complained about “grade inflation” among critics who overvalue heartwarming work. I complained about an article that outed an anonymous tumblr weirdo just because this person may possibly be a little too weird. I complained about Chuck Schumer praising George W. Bush for “bringing the country together” after 9/11. I complained about the billionaire fuck who shut down a whole raft of journalism sites he’d purchased a few months ago because the employees voted to unionize.

All of these touch on my career, my politics, or both, and these things are important to me. But it’s noteworthy, I think, to isolate the emotion Twitter seems to count on to drive you back to that empty white box. Yesterday, for example, it took all I had to stop myself from kvetching about people saying Mad Max: Fury Road is the greatest action movie ever made when it’s, maybe, the third-best Mad Max movie ever made. (Now I’m doing that here where you suckers have to see it instead.) Again: career-related, sure. But my desire to use Twitter is directly correlated to how much I think my career fucking sucks at any given moment. Can you think of any other business or activity that functions in this way?

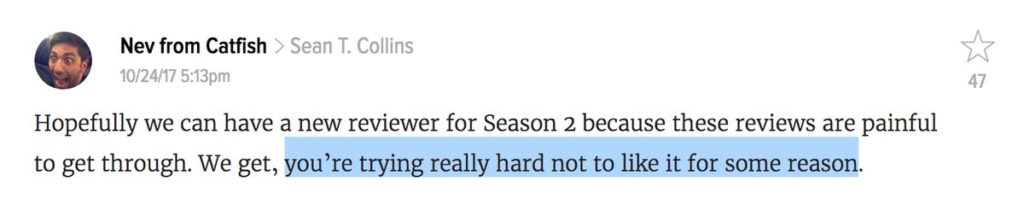

who watches the watchmen

November 3, 2017

I know it shouldn’t, but it shocks me how people who devote time to criticizing arts criticism can understand so little about arts criticism.

BTW, not that you should go by letter grades, but my averaged-out grade for the show I tried really hard not to like for some reason? B.

(PS: That’s not really Nev from Catfish)

Thought Leader

June 30, 2017

I really couldn’t ask for a more delightful criticism of my Game of Thrones Evil Rankings than Ross Douthat defending the High Sparrow

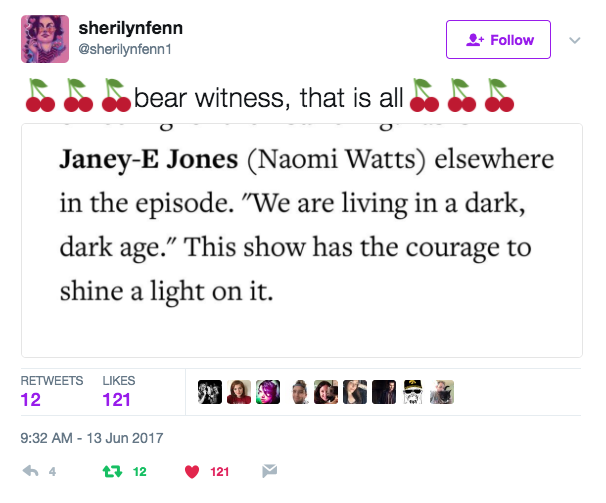

“bear witness, that is all”

June 14, 2017

Sherilyn Fenn, aka Audrey Horne, quoted my review of the latest Twin Peaks and added a bunch of cherry emojis. So I’m dead now,

‘The Godfather’ Was Really the First Great Prestige TV Show

April 24, 2017Not to get all Beavis and Butt-head about it, but bad shows suck because, well, they suck, not because they are insufficiently episodic in structure. This is why calls from the critical community, leading many of the fan conversations on these shows, to eschew unified, serialized storytelling in favor of tight arcs and standalone episodes feel like a misdiagnosis. For one thing, they fail to consider that noticeably self-contained installments of series like Game of Thrones and Girls are as memorable as they are precisely because those shows don’t usually work that way.

These claims fall into the same trap of cinematically minded showrunners who insist that “it’s not TV” by agreeing with them, setting up a false dichotomy between what constitutes the proper use of the medium and what doesn’t. In its maturity, television has proven capable of countless things: TV dramas alone can be as densely serialized as The Wire Season 4, as memorably episodic as Mad Men Season 5, as sweeping as Fargo Season 2, and as sensation-driven as Empire Season 1. Sometimes they can be several things at once; Black Mirror, like its groundbreaking antecedent The Twilight Zone, tells a different story with a different set of characters every single episode, making it simultaneously one of the most movie-like and most episodic shows on television. Saying any of these series is closer or farther away from The One True Way to Make TV obscures the fact that there’s no such thing.

In fact, this array of options, this wide-open landscape of different structures and tones and techniques, is the truest indicator that “prestige TV” is not a contradiction in terms. Problems with the execution aside — and problems with the execution is all they really are — television can do whatever you want it to do at this point, and declaring one approach or the other superior is a procrustean blunder — like arguing The Godfather is less great a film because you can break it down like a television series, if you’re feeling particularly perverse (ahem). If that means some showrunners get to declare their series a double-digit-hour movie, so be it. The proof will be in the pudding, or the cannoli. You can have it both ways. Why wouldn’t you want to try?

What was your favorite episode of The Godfather? “Khartoum”? “The Thunderbolt”? The pilot, “I Believe in America”? I presented a modest proposal about a cinematic classic in order to talk about where all the “no, your TV show isn’t a 73-hour movie” structuralist reprimanding gets us for Thrillist.

Now More Than Never

December 8, 2016I’ve read as little as possible of anything other than Lovecraft and books about glam rock for the past month or so, but when I stumble across essays on the intersection of politics and popular culture, it’s always “Why X Matters Now More Than Ever in the Age of Trump,” where X is always the exact same fucking things everyone said mattered before the Age of Trump. Maybe they did, maybe they do, but maybe we should be looking for something else.

STC on Inkstuds

October 28, 2016I’m the guest on the latest episode of the venerable comics podcast Inkstuds, hosted by Robin McConnell. I talk about comics, TV, criticism, my history with all three, the Greatest Graphic Novels list I recently did, goth, the anthology @doopliss and I are doing, and more. Check it out!

How to look at an actor

July 14, 2016Though I studied film in college, I came to TV criticism through comics criticism. In comics, everything on the page is intentional. Character design, line weight, color, panel size and arrangement, backgrounds, lettering: A human being set all those things to paper. Every aspect of the image is considered, deliberate. (Obviously personal style is not entirely within an artist’s control, but that’s basically how it works.)

So when I started writing about television, I realized my writing was informed by this not just in terms of how I talked about cinematography, editing, and the like, but with regards to the actors. The look of a face, the sound of a voice, the size and movement of the body, physical comportment: I discuss these as the equivalent of line, design, and so on in comics. This has played a major role in how I’ve processed any number of shows; for several (Boardwalk Empire, Downton Abbey) it may well have been the central thrust of my writing on them. I’m happy with the writing I’ve done driven by this rubric, but the larger point I’d like to make regards thinking about actors visually. Since television and film are visual media, I think this is valid and vital and, if anything, underdone. But there’s a way to do it without objectifying actors, either sexually or as “other,” as several recent high-profile essays on women actors have done.

If you’re a straight man, for example, write about the physicality of men, to whom you’re not sexually attracted. See how it shapes what you say. How Jon Hamm looks, how James Gandolfini sounds when he breathes: These are important aspects of Mad Men and The Sopranos respectively, but not of your sex fantasies. When you write about women actors, you can talk about how they function physically on-screen in the same way—observing, not objectifying. Do this in the context of their work, not how they look eating lunch. Don’t lead with it. If sex/sexuality is part of the role, fine, but try not to sound like you’re sexting or seducing, and talk about their male partners too. Fold your discussion of actors’ physicality into the show or film’s physicality as a whole—wardrobe, set design, sound design, good old-fashioned shot composition.

We need more film/TV writing that’s about more than plot, dialogue, line readings, showbiz talk, and political subtext. Actors are a part of that. We need to write about the appearance of actors, women and men, without it devolving into Penthouse Letters. It can be done!

Art, empathy, and Hal’s Emerald Attack Team

June 11, 2015mramgine asks: Are you familiar with the controversy surrounding what happened with Green Lantern back in the 90s, where Hal Jordan was turned into a supervillain and fans got so pissed that some sent death threats to DC? Why do you think certain creative decisions in media cause such reactions? Are some of these people mentally disturbed or is there some other reason for such behavior?

The Four Worst Types of TV Critics

April 16, 2015“People love hearing how right they are.”—Agent Stan Beeman, The Americans

Last year on Game of Thrones, Jaime Lannister raped his sister Cersei. At least that’s what he did in the scene I saw. Statements on the matter by actors Nikolaj Coster-Waldau and Lena Headey and director Alex Gravestalked about two people in a deeply dysfunctional relationship having sex they knew they shouldn’t be having, not that one person was refusing to have at all. Co-writer and showrunner David Benioff appeared to disagree in an interview taped prior to the episode’s airing, before adopting total radio silence on the issue. The show’s subsequent handling of the characters, author George R.R. Martin’s comparison of the scene to its equivalent in his original books, and further discussion by the actors provided still more complicated and confounding context. We could perhaps conclude that either through communication breakdowns between the players or a failure of execution to mirror intent, the scene — rooted in complex and destructive sexual dynamics between two habitually secretive and duplicitous characters and interpreted by half a dozen artists each with their own ideas about the event — simply got away from them.

Few of us did. Fans of the books lambasted the scene as yet another horrendous, story-destroying decision by Benioff and his creative partner Dan Weiss, two people frequent treated as singularly unsuited to the task of adaptation. Admirers of Jaime bemoaned the damage done to him by the event at least as much as his sister, the victim. Critics saw the scene as a romanticization of rape, using the show’s long and contentious history with female nudity, sex, and sexual assault to support the argument. And while the wider world focused in the latter of these three critiques, the former two were no less self-assured or severe in their respective corners of the critical firmament.

On one level, the reaction to what happened between the Siblings Lannister in the Great Sept of Baelor is just a standout example of the golden rule of arguing on the Internet: interpret with minimum good faith, attack with maximum rhetorical force. But that rule applies to discussions of everything from politics to fly fishing. In terms of art and art criticism, something else is going on—a phenomenon of which the social-justice framework for criticism is just the most well-publicized, hotly debated embodiment.

The past decade-plus has been a time of dispiriting uncertainty and powerlessness: an era of endless war, economic erosion, class disconnection, and political disillusion. At the same time, our approach to art and entertainment has become all the more unequivocal in its assertions about content and quality. We pore over TV shows for clues about their outcome, which we present with power-point precision. We treat all art like editorial cartoons, interpreting it the way we would a drawing of a fatcat politician holding bulging moneybags in each hand, and accept or reject the story accordingly. We treat the comics and novels that form the basis for our blockbusters as holy writ, we insist that fiction hew inerrantly to the facts that inspired it, and we punish those who stray from the path. We elevate our favorite characters and relationships to the point where the stories they inhabit are mere vehicles to get them to the place we’d like to see them go.

In all four cases—the Theorists, the Activists, the Purists, and the Partisans—we’re treating the inherently subjective fields of art and art criticism as things we can be objectively right about. We’re taking work that’s complex and capable of conveying multiple contradictory meanings and reducing it to a simple either/or, yes/no proposition.

In other words, we’re fucking up.

I wrote about the four worst types of TV critics for the Observer.

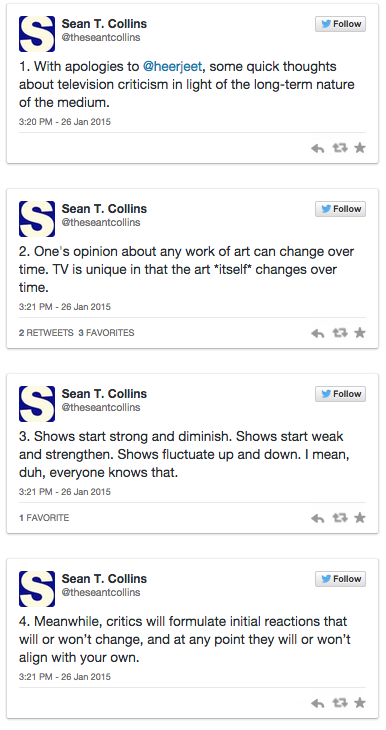

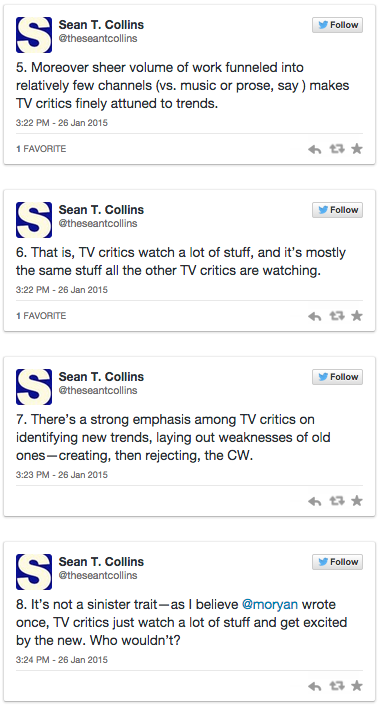

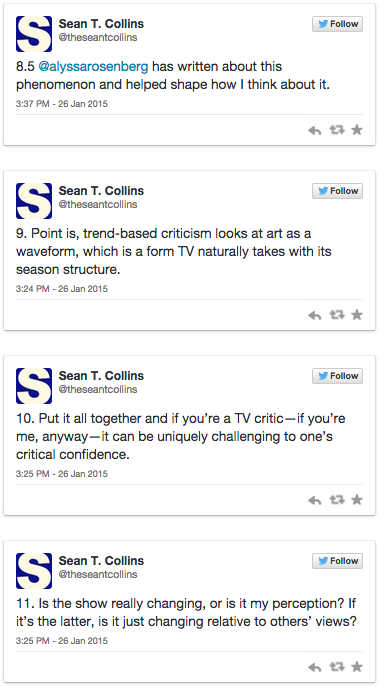

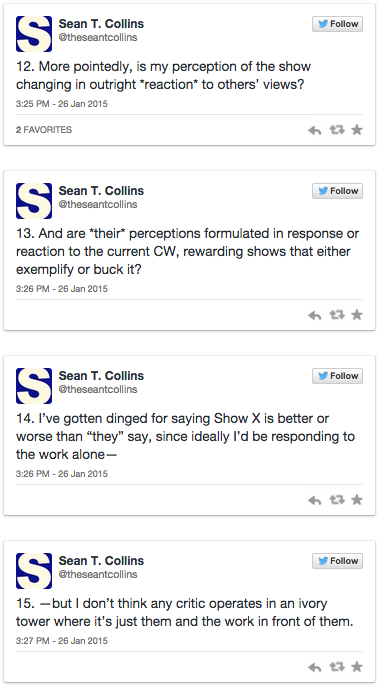

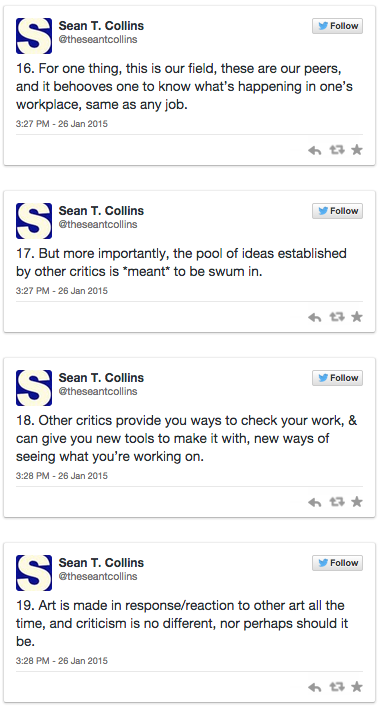

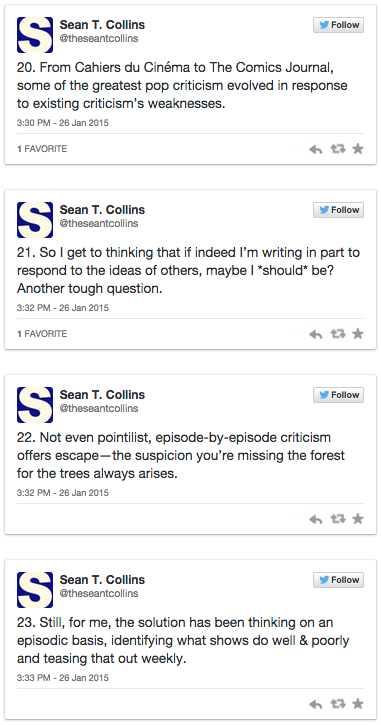

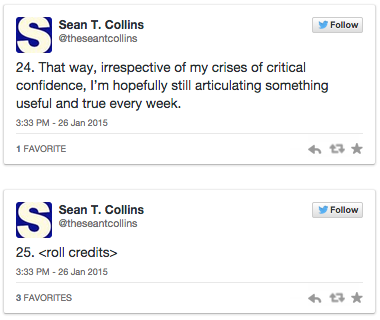

TV criticism and crises of confidence

January 27, 2015I tweeted some thoughts on TV criticism and crises of confidence in light of the medium’s long-term nature. They were brought to you by the news that I’ll be covering The Americans for the New York Observer this season.

On “objective criticism”

December 31, 2014dagsg asked: Do you have any opinion why, when some piece of art (e.g. GoT) might appear to be have dodgy or questionable elements (or changes in many cases) in closer inspection, modern fandoms almost always suspect malevolence behind it? Instead of explaining it with usually more plausible ignorance and/or stupidity (which also might sound a bit harsh in some cases).

I’ve written about this before, I know, and I’m sure more articulately than I’m about to, but: In contemporary criticism of art, both professional and fandom-based, several prevalent approaches that on the surface appear to have little in common are all methods of doing the same thing, which is turning the evaluation of the work, which in the case of both the evaluation and the work is something inherently subjective and complex and capable of containing multiple contradictory messages and meanings, into something objective and simple.

“Purists” turn to fidelity to the source material. “Social justice warriors,” whether that term is being externally applied as a pejorative or self-applied as a tongue-in-cheek but proud descriptor of priorities (and I would consider myself the latter; it’s one of the reasons I started this tumblr years ago and started writing about this material in this way), as well as their reactionary opponents, apply sociopolitical metrics. Theory-mongers focus on “solving” art by teasing out clues and connections to unearth hidden truths or predict a work’s conclusion. Stans, shippers, even the “bad fans” of antiheroic characters so frequently lamented by film and TV critics who find them in the comment threads and twitter exchanges resulting from their reviews, prioritize the treatment of their favorite characters and relationships.

But in each case, the end result is a way to feel fairly to totally confident that art can be right or wrong; that the artists who make it, to speak to your question directly, can be right or wrong and condemned or praised; and that you, as a critic, can be right or wrong about that art and that artist in turn. Each approach has its legitimate benefits — in particular I believe that politics are a part of all art and MUST be addressed and considered — but each approach is ultimately reductive and contrary to what I understand art and criticism to be if no further steps to interrogate the work and one’s feelings about it are taken. Art is big and messy. Making it, consuming it, writing about it — these are inherently risky propositions. The risk should be embraced if we are to do anything worthwhile.

Oral history lesson

May 1, 2014A couple weeks ago Jessica Hopper published an oral history of Hole’s Live Through This, and it had been a very long time since I reacted to a work of criticism so intensely so quickly.

For one thing, speaking as a writer who’s done one in the past, this is an achievement in using the oral-history form to reveal information, rather than aid in cloaking it through self-mythologization. It’s so easy to do that with these things. Shit, it’s baked into the premise of the enterprise: Look at my proximity to all these people’s proximity to greatness!

But it’s not that Hopper doesn’t include all the choice nugs you’d want in an oral history — you know, anecdotes about meeting RuPaul while hammered at the SNL afterparty, differing accounts of how badly Courtney Love wanted to work with Butch Vig, etc. It’s that she treats it not just as a history of a cool thing, but as reporting on that thing. She digs into how the studio was selected, how the personnel came together, what the schedule was like. She digs into the rock climate at the time, the (limited) involvement of Billy Corgan and Kurt Cobain, the (profound) influence of Siamese Dream and Nevermind. She digs into drug use, who was doing what and when. She talks to band members, producers, label people. She lets Love hoist herself by her own petard when that’s called for, but she also lets her emerge, then and now, as someone who had a very clear artistic goal and worked, successfully, to achieve it. Inner torment and commercial ambitions and improved songwriting chops and a better rhythm section and working with a guitarist with little self-confidence and hiring skilled producers and developing a workday routine and navigating the demands of other prominent artists in the field with whom she was close — it all went in and that record came out, and Hopper gets it all down. I suppose she’s lucky that she got such a forthcoming group of interviewees, since god knows that’s rare, but luck’s a fundamental part of a good piece too.

I didn’t listen to Hole in the alt-’90s heyday; didn’t buy the “Yoko” nonsense either, that just didn’t seem to cut any more ice here than it does with actual Yoko. And there’s no way to be judgmental about Love as a parent without being more so about the one who isn’t there anymore at all, so I think I gave that a pass over the years as well. Point is I didn’t have much riding on reading this either way. But what a fascinating document of the making of a work of art, and what an inspiring example of how to write about art. It makes me want to work harder.

On becoming an “expert”

September 6, 2012A while back I answered a question about the intensity of my A Song of Ice and Fire/Game of Thrones fandom that wondered whether I’d ever felt this strongly or invested this much time and energy into another author’s work. The answer was yes and no: felt this strongly, sure; invested this much of my life, no. (Not unless you count “comics” as a whole; writing and thinking about comics has basically been my life’s work.) Even today I think I could just as easily be operating a tumblr and opining professionally about Los Bros Hernandez, or Clive Barker, or the band Underworld, or David Bowie (hey, wait), or ’70s glam rock, or Chris Ware, orThe Sopranos/Twin Peaks/Breaking Bad/Mad Men/Battlestar Galactica/Deadwood, or or or. But A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones it is. And it’s really remarkable how quickly my little “career” as an ASoIaF pundit took off, given how vanishingly little effort I put into getting it started!

I started my ASoIaF blog All Leather Must Be Boiled in March of 2011. My daughter had just been born two months prematurely via emergency caesarean section following another two and a half months of pregnancy complications that required my wife’s repeated hospitalization and lengthy bedrest stays, during which time one of our cats was diagnosed with cancer and was also both hospitalized for surgery and confined to a bedroom for recovery. I’d spent a quarter of a year running from work to hospitals to home, caring for the beings I loved as they suffered. A work as grim as ASoIaF was an odd choice for “escapism” to be sure, but it seemed to do the trick, because it confronts serious issues — issues that truly haunt and hound me day to day — in a way that also helps blow off steam about those issues.

So one day I got back from visiting my daughter in the neonatal intensive care unit during my lunchbreak, sat down at my desk, and decided to fire up the old tumblr dashboard and launch a new ASoIaF-only blog. This way, the things I wanted to say about the series would neither spoil it for readers of my other outlets who were interested in catching up, nor drown out everything else I write about for readers who weren’t. Simply choosing to use Tumblr instead of, say, WordPress indicated, to me at least, how casual the thing was going to be. Most of my initial posts were written for an audience of one: me — stray thoughts, things I caught myself, passages I loved, a play-by-play of my journey of discovery through Westeros.org’s archives and forum, fanart drawn by cartoonist friends and acquaintances, anticipatory effusion about the then-upcoming HBO show. It was truly the tumblr of a fan, not a scholar, barely even a critic.

The point is, I learned as I went, simply through going. The more I wrote, the more I found myself able to articulate what was important to me about the books, to formulate coherent questions about the things I didn’t understand, to provide answers about the things I thought I did understand, to find answers on my own and put them in front of other people. Very quickly, “other people” expanded to include people who really were experts. Elio Garcia and Linda Antonsson from Westeros.org said nice things, popped up in the comments, and eventually got me hired to work on the official annotations of A Game of Thrones alongside Elio and the books’ freaking editor, Anne Groell. That happened within six months of me starting this tumblr. Stefan Sasse from Tower of the Hand liked what I was doing enough to suggest we start a podcast together, and voila, The Boiled Leather Audio Hour was born. The writing I was doing about the show (and other shows) was apparently solid enough that when I mentioned how much I’d love to get paid to do what I’d been doing for free to my friend Matthew Perpetua, who was an editor at Rolling Stone, he passed my name to his fellow editor Evie Nagy, who hired me to recap Game of Thrones within days of me just idly “wouldn’t it be nice”-ing this during a google chat. Because of the way I write, and the things I write about, and the place I write about it, I find myself in the central overlap of a Venn diagram that includes traditional, Westeros-style fandom, professional pop-culture critics, and the tumblr ASoIaF/GoT community. Best of all, this doesn’t only work in one direction: One day I clicked on a tumblr that had just followed this one, discovered an incredible, fully-formed music critic at the tender age of 18, and passed his name along to the right people, so that I think he was offered his first pro music crit gig within literally hours. (What up, Jaimeson?) To call All Leather Must Be Boiled the most rapidly rewarding writing I’ve ever done would be to understate the case considerably.

And the rewards, in the form of knowledge and enjoyment of that knowledge at least, never stop. As I said earlier, one of the best things about this blog is the chance it gives me to be wrong about things in public. That way, the people who know more than I do can provide me with the right information, and I can grow and learn and get more right in the future. What a wonderful opportunity! It’s a joy to be corrected by Elio, or enlightened by Stefan, or challenged or outright debunked by another tumblr. I want to get better, and that’s how you get better. I think that because I started this tumblr with no pretensions to expertise, simply the desire to talk about these fun books I read, I was responded to in kind. The vituperative, “SOMEONE IS WRONG ON THE INTERNET” responses I’ve gotten to anything I’ve ever said there can be counted on one hand; even then I try my best to put the tone aside and focus on what they’re telling me that I wasn’t seeing or hearing myself. Sometimes they’re just wrong, of course — hey, I’m a critic, I’m going to think other people are wrong, that’s what they pay me for — but most of the time they’re shining a light on something I could’ve used a clearer look at. You can bet your bottom dollar that I take that experience to heart and try my best to apply it to everything I do, online and IRL. There’s no better way to become an “expert” than to do, and do, and do, and sit back and see what comes of the doing.