Posts Tagged ‘AdHouse’

Comics Time: Pope Hats #1-2

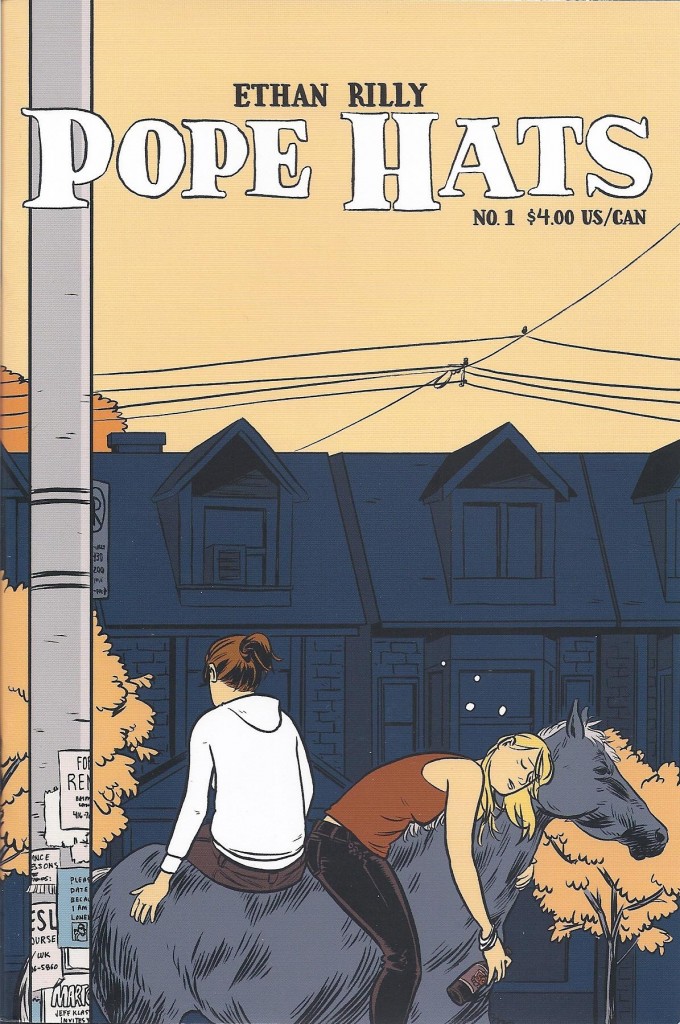

March 13, 2012Pope Hats #1-2

Ethan Rilly, writer/artist

#1: self-published, 2009

32 pages

$4

Buy it from AdHouse

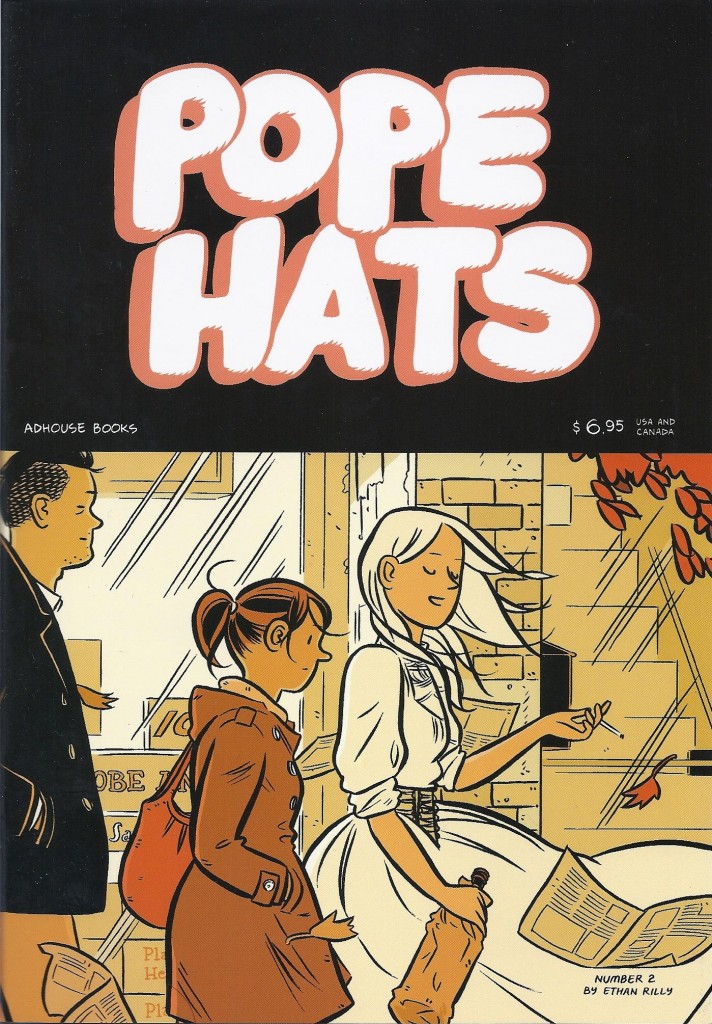

#2: AdHouse, 2011

40 pages

$6.95

Buy it and read a preview at AdHouse

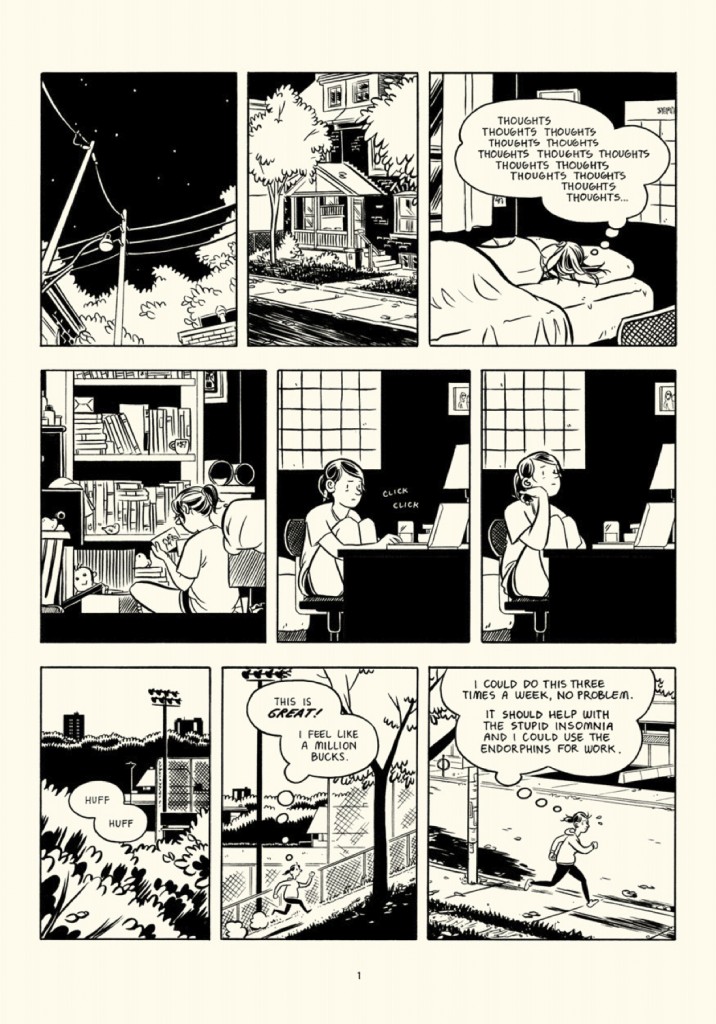

You know, I was gonna be harder on these before I started flipping through them again in preparation for actually writing this review? I have no objection to slice-of-lifers, obviously, even stylized ones like these — the kind where everyone’s dialogue is constantly “on” (“Don’t you want to say goodbye to Peter?” “If by Peter you mean ‘my bed’ and by goodbye you mean ‘pass out in,’ then yes. Yes, I want to say goodbye to Peter immediately.”), and where the lead occasionally talks to a cartoon ghost, and has a boss who looks like the Kingpin, meditates in the lotus position in his office, dictates all his correspondence (including grocery lists) to three assistants in lieu of owning a computer, and lives in an adjoining hotel so he never has to go outside. What’s more, Rilly’s cartooning is absurdly proficient and elegant. I wish I could remember who I’m stealing this from because it’s the perfect way to describe it, but you really could sit Rilly down next to his fellow (mostly) Canadians in the core Drawn & Quarterly line-up — Seth, Adrian Tomine, Joe Matt, mid-period Chester Brown — or for that matter next to Los Angeles’ classy classicists Jordan Crane and Sammy Harkham, and he wouldn’t look the slightest bit out of place. But speaking of fellow Canadians (and of Los Angelenos, at this point), there’s a healthy dose of Bryan Lee O’Malley’s comparatively contemporary portraits of young urban semi-professionals in there along with the standard Gray/Segar roots, an influence the aforementioned snappy, showy speech and not-quite-magic realism only make clearer by the end of Pope Hats‘ second issue. The problem is that it’s all a bit too dazzling to actually get into, at least for me. Every word uttered, every gesture gestured by studious law-clerk lead character Frances and her drunken whirligig actress roommate Vickie is designed to drive home just how them they are at all times. If the story, such as it is at this point, is one of young people feeling locked into the personae and professions they’ve chosen themselves, then Rilly’s conveying this all too well — I never felt like the characters had been given the freedom to surprise him or me. (You could perhaps say the same for the whole package as comics, if you were feeling less than charitable. The random-ass title, the self-effacing tone of various bits of incidental copy here and there, supplementary short stories in which ironically verbose schmoes wax philosophical about the ineffable joy and dread of modern life — the only way it could be more of a ’90s altcomix solo-anthology throwback is if it had a letter column full of people asking permission to turn it into a student film.)

But that’s all just how I remembered the comics from my initial read; much of it vanished upon that aforementioned flipthrough, which ended up feeling like a tour of Pleasuretown. For all I may object to the flippant patter, Rilly has a terrific eye and ear for the intersection between a person and her job, and how what she does during work hours and off hours alternately aligns and contrasts in revealing ways. Vickie is a manic pixie dream girl for guys and something of an alcoholic trainwreck for her roommate Frances, but she’s also a compelling actress in local productions. Frances is dutiful at work and at home to the point of drudgery/neurosis, but she tells a pair of spooky true stories at the end of issue #1 — in medium-closeup direct-address Brian Bendis fashion, no less — that both showcase how well comics can do that sort of thing and demonstrate how her attention to detail can manifest itself as an engaging facet of her personality during her free time. Issue #2’s backup story “Gould Speaks” hits its “intellectual blowhard actually quietly emotionally wrecked by a breakup” note a little hard for my taste, but watching Rilly fill out the space of the bus on which the title character is taking a cross-country trip by almost constantly shifting angles from panel to panel is a multi-dimensional joy, and when the true meaning of the story’s title is revealed, I laughed out loud. And of course there’s the fact that Rilly is a fucking phenomenal drawer — of hair, of ceiling fans, of city streets, of bar interiors, of beds, of pretty much anything. See the cover of issue #2? The inside’s just as pretty. It’s that kind of comic. In other words it’s a good kind of comic — it could be better, yeah, but isn’t that what issue #3 is for?

Comics Time: Duncan the Wonder Dog

December 27, 2010

Duncan the Wonder Dog

Adam Hines, writer/artist

AdHouse, September 2010

400 pages

$24.95

Buy it from AdHouse

Buy it from Amazon.com

In theory this couldn’t be more down my alley: Graphically and narratively ambitious funny-animal allegory set in a world where animals can read, write, and talk, dealing unflinchingly with animal rights and animal cruelty. So why did it never fully get me on board?

Several reasons. First and foremost is the decision to eschew black and white for graytone, casting a smoky haze over every panel and turning me off on a visual level right from the get-go. I actually double-checked to make sure I wasn’t accidentally reading a galley, that’s how odd and dreary it looks. The bitch of it is that the shading and backgrounds are frequently nuanced and complex enough to conjure in your mind what this would look like in color, even just spot color or duotone, and the comparison isn’t flattering — it obscures more than it reveals. Meanwhile, for all of Duncan‘s substantial visual ambition and formal play, I never found writer-artist Adam Hines’s actual cartooning convincing. His characters seem not quite fully formed to me, the figurework just a little flaccid and unfinished, their dot-eyed cuteness recalling a webcomic that’s pleasant enough to look at but not anything that feels like a unique vision of how to construct a person or a world.

Hines’s real chops come in the artcomix elements of the book — flashes of photorealism utilized in Dave McKean-style abstract-comics fashion, extensive formal tomfoolery with text and graphics, and a plethora of narrative approaches that includes radio broadcasts, diaries, fourth-wall-breaking Q&As, streams of consciousness, textbooks, dreams and flashbacks, fairy tales, and straightforward storytelling. But there are problems here as well. Much of the text-heavy material comes across as overly verbose, overselling the points being made not just by the characters but by Hines himself in switching to whatever particular new format he’s using at the time. The dialogue in particular can get downright Bendisian at times, too in love with the sound of its own voice to truly evoke the naturalism it’s going for. Not always, mind you — sometimes it works great, usually when characters at cross-purposes must talk to each other as opposed to when people are sounding off monologue-style. But often those conversations are followed by a too on-the-nose journey into one of the participants’ heads via captions, and the verbal overload begins anew. Similarly, the visual flourishes swing for the fences, but they feel disconnected from the simple cartooning and character designs and thus took me out of the story rather than suggesting a world of transcendence and mystery beyond the frequently sad and unpleasant actions of the actual characters.

Those characters are undoubtedly Duncan‘s strong point. The asshole bigot politician who’s actually ruthlessly intelligent and self-aware as well as ambitious, the activist gibbon who through sheer will has gotten a seat at the table of power but will never really be welcome there, his human wife and the front of jovial “so-what” strength she must maintain, the anti-terror agent who sees his job as just a job yet has somehow found himself in the arch-nemesis slot for the animal kingdom’s Manson/Bin Laden figure, and that figure herself, a gratuitously cruel and hyperactive monkey whom the genuine injustices faced by animals in this world have literally driven insane. Just in writing that recap down I’m struck by how…well, to use a phrase I used earlier, fully formed these characters are. They’re fun to spend time around, however flat the logistics of their depiction may leave me, and I’m quite excited by the notion that Hines apparently has nine volumes of their lives planned out.

But here’s the thing: If I had their lives, any of their lives, I’d be a whole lot angrier. And maybe that’s my most fundamental, and surely my most personal, problem with Duncan the Wonder Dog: It just doesn’t come across as apocalyptically angry, which let’s be frank is how I feel when I think about animal rights. Reason-destroyingly, misanthropy-generatingly angry. Rooting for the terrorist monkey as she blows up colleges and shoots people in the face angry. I can’t really elaborate on this very much; it would degenerate into a barely coherent lecture and make me look ugly and foolish and hateful. But if I were to make art about animal rights — specifically, if I were to make a graphic novel about a world in which animals and animals have always been able to speak to one another and be understood, yet in which virtually nothing about the way we torture and slaughter countless millions of animals every day is any different from the way it is on this world — I want ugly and foolish and hateful. Duncan‘s ambition leaves it very little time for any of those things, and that’s a shame.