Archive for May 29, 2014

STC @ CAKE

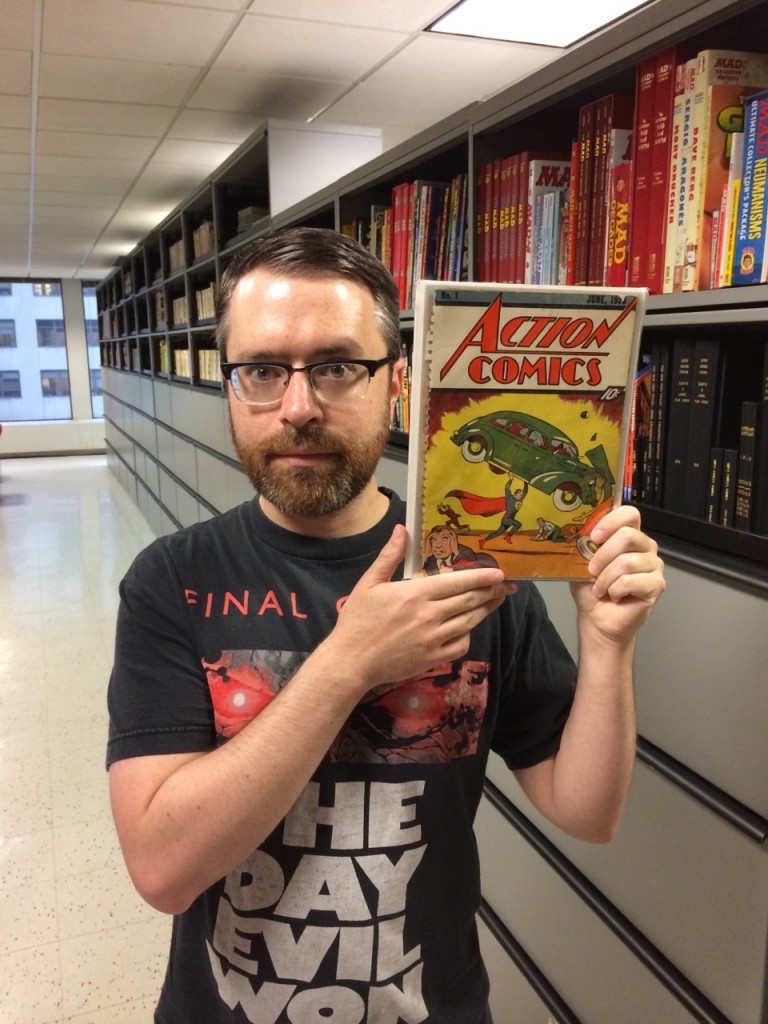

May 29, 2014Come see me at CAKE, the Chicago Alternative Comics Expo (the “k” is silent, and invisible), this weekend! I’ll sporadically be at table 68A with Julia Gfrörer, hawking our Edgar Allan Poe porn comic In Pace Requiescat and potentially Flash Forward by me and Jonny Negron too, and I look like this.

“Mad Men” thought, Season Seven, Episode Seven: “Waterloo”

May 26, 2014“One small step for a man. One giant leap for mankind. One enormous problem for Peggy Olson.

On the eve of the biggest pitch of Peggy’s life, human beings walked on the surface of a celestial body other than the Earth for the first time in history. Bad enough if they died in the attempt, but their success is hardly a solution for her either. “I have to talk to people who just touched the face of God about hamburgers,” she laments to Don Draper when he passes the cup from his lips to hers.

But Peggy, it turns out, is a prophet. And like any prophet worth her salt, she speaks with God’s voice. She speaks of Burger Chef as if its fast-food formica is the Ark of the Covenant, a vessel with the power to bridge the generation gap and end the conflict over Vietnam, if not the Vietnam Conflict itself. At home, she argues, our connection with each other—the connection we all keenly felt as we watched Neil Armstrong take those first shadowy steps—has been severed. Not so at Burger Chef: “What if there was another table where everybody gets what they want when they want it?”

That’s the theme of “Waterloo,” the “mid-season finale” of Mad Men‘s final season. In this episode, desire—particularly the desire of women—is fulfilled. Wishes are granted, closure is reached, and even death becomes a song-and-dance number. What makes “Waterloo” one of Mad Men‘s finest hours is the way it delivers all that catharsis, yet still questions what happens to it after the curtain comes down.”

I reviewed Mad Men‘s marvelous final episode of the year for Wired.

“Mad Men” thoughts, Season Seven, Episode Six: “The Strategy”

May 19, 2014“What if there was a place where you could go where there was no TV, and you could break bread, and whoever you were sitting with was family?” This isn’t just the new Burger Chef advertising angle that Peggy Olson had been searching for—the strategy that gave last night’s Mad Men its title. It’s damn near a mission statement for the whole series, now entering its home stretch. Back in Season One, Don’s legendary “Carousel” pitch leveraged nostalgia for family as the ultimate inducement to buy. Nearly a decade later, the definition of family is changing, but the need for what it represents—safety, loyalty, love—has never been stronger. Don, Peggy, Pete, Joan, and Bob have all learned this the hard way. Now they’re gonna use it to sell burgers.

Mad Men was so good last night that at one point I was literally sitting there with my jaw hanging open and my hands on my face, Kevin McCallister-style. I reviewed it for Wired.

“Game of Thrones” thoughts, Season Four, Episode Seven: “Mockingbird”

May 19, 2014“You cannot give up on the gravy.” So declares Hot Pie, former running buddy of Arya Stark and budding Great Chef of Westeros, to an unappreciative Brienne of Tarth and Podrick Payne. All they signed up for was a square meal and a place to spend the night on their quest for Sansa Stark. Instead, they get a monologue from a refugee from Flea Bottom who can’t stop talking about what makes for a good pie. Eventually, the kid gives them information they find a bit more useful: Arya’s alive and headed for her crazy aunt Lysa’s place. He also dropped some science: Westeros may be a hellhole of murder and deception, but individual moments of pleasure and kindness are all the more vital for it. Ice demons, zombies, dragons, giant sword-wielding maniacs, it doesn’t matter: You cannot give up on the gravy.Or the hot sauce, for that matter. For all that we critique the show’s handling of nudity and sexuality, we should probably also celebrate it when it’s, you know, sexy. To wit: Daenerys Targaryen, Mother of Dragons, getting some of that Daario D. Henry Kissinger once called power “the ultimate aphrodisiac,” but it’s unlikely he realized that it applies not just for those in the presence of power, but for those who wield it as well. Dany is intoxicated by her command of this swaggering sellsword, and the master/servant dynamic she establishes by making him drop trou in front of her – and the audience, woo-hoo! – is intensely erotic. The look on her face as she stares at Daario’s exposed Naharis? Hot as dragonfire.

I reviewed last night’s Game of Thrones episode for Rolling Stone, and for once I got to write as much about sex as I did about violence. Wheeeeeeeeeeee

Gordon Willis 1931-2014

May 19, 2014“Godzilla” thoughts

May 18, 2014For letting the trailers fool me, I deserve what I got. I mean, to be fair, they didn’t fool me, exactly — I’m well aware that you can make a good trailer out of pretty much any film. But the movie promised by the trailer was very much my kind of movie: well-acted horror in which the horror dwarfs and makes mock of human ambition and self-conception.

But Godzilla‘s not a horror movie, it’s a blockbuster, and by that I mean blockbuster-as-genre, with all the faults that entails: cardboard-cutout leads, buildings meaninglessly collapsing, paper-thin women characters, and the glories of the U.S. military. (Yes, in a Godzilla movie! No, mentioning Hiroshima once doesn’t cut it!) Everything that was beautiful, moving, and scary in the trailers is beautiful, moving, and scary here, but with the exception of some unexpected and laugh-out-loud funny swipes at CNN, that’s the extent of the film’s value.

The soul of those trailers, Bryan Cranston, is absolutely amazing here, displaying total commitment to the work and bringing me to the brink of tears. The problem is that he’s so much better than everyone else in the movie that (SPOILER ALERT) when he dies at the end of the second reel, any incentive to give a shit dies with him. Seriously, did they not see the problem that sticking with this twist idea would cause? He’s so incandescent in every moment he makes everyone else look like the movie was some kind of community-service sentence. Poor Ken Watanabe is given nothing to do but glower his way through some exposition, and David Strathairn’s disinterest is so palpable I half expected him to take off his mic and walk off the set at any moment. The one exception is Juliette Binoche, but she dies even before Cranston does. Perhaps Cranston’s early departure was mandated by budget or scheduling, but all I can do is critique what wound up on screen, and it’s not even a matter of a counterfactual wherein his character was the lead instead of Aaron Taylor Johnson’s nothing of a Navy bomb technician: His character was the lead for half an hour, and that’s when it was a good movie.

Godzilla has strong kaiju visual effects, certainly stronger than those of Pacific Rim; you watch this and you just think Guillermo Del Toro should be even more embarrassed for himself than he already ought to be. But it’s hardly novel in that regard: The Mist and especially Cloverfield pioneered the use of modern-day CGI to convey the horror of scale, and in those films the one-dimensional characters and hackneyed tear-jerking moments are more easily forgotten since they really are horror movies, and really do try and occasionally succeed to be frightening and bleak. For all the ranting about how Gojira will send us back to the Stone Age, this is no apocalypse: Godzilla‘s supposed to leave you cheering and hungry for the sequel. It lacks the courage of Cranston’s convictions.

I should not have been trusted with this

May 16, 2014The Boiled Leather Audio Hour Episode 29!

May 16, 2014Conquest!: GeorgeRRMartin.com’s Aegon Targaryen-centric “The World of Ice and Fire” Excerpt

Another week, another sample from something Good King George has got cooking — if, of course, by “another week” you mean “last week.” Yes, since Stefan and I recorded this episode, yet another excerpt from George R.R. Martin, Elio Garcia Jr., and Linda Antonsson’s worldbook The World of Ice and Fire has been released. No matter! Like the modern-day maesters we are, we stay focused on the matters at hand, specifically the sample unveiled on GeorgeRRMartin.com regarding House Targaryen’s flight from Valyria and Aegon’s Conquest of Westeros. The sample raises many intriguing questions — indeed, more than it answers — on everything from the bloody century the Targaryens spent on Dragonstone between the Doom and the Conquest to Aegon and his sisters’ adoption of the Faith of the Seven. After Stefan and I discuss these matters, we follow up on a related Tower of the Hand roundtable and ask what place supplementary materials like this should even have in a work of narrative fiction. Saddle up, dragonlords!

“Game of Thrones” thoughts, Season Four, Episode Six: “The Laws of Gods and Men”

May 13, 2014for the trial of Tyrion Lannister, the throne room is transformed into something more like a circus, or the ringside seating area at a particularly lopsided boxing match. On the kind of bleachers Westeros normally reserves for the audience at jousting tournaments, the lords and ladies of King’s Landing gather round to watch the Imp’s chickens come home to roost: the Kingsguard he antagonized; the Grandmaester he imprisoned; the sister who despises him; even Varys, the friend who could never be anything but fair-weather. Watch how much work is done here by the camera alone, framing Tyrion all the way over in the lower left-hand corner, squashed into exhaustion and irrelevance by the kangaroo court that surrounds him.

It’s only when his father Tywin calls his son’s former girlfriend, Shae, to the witness stand that Tyrion, a passive participant in his own trial, becomes the star of the show. Her unexpected appearance (even the “Previously on” teaser, which dutifully reminded us of Tyrion’s previous beefs, kept her return quiet) was galvanizing and devastating, especially after the sudden relief of the previous scene. Jaime’s deal with Tywin – Tyrion’s life is to be spared, and he gets sent to the Night’s Watch in exchange for Jaime becoming heir to House Lannister once more – might have seemed too good to be true, but hey, this show does bigger surprises than that all the time. Undoing it so quickly was almost cruel.

Crueler to no one than the two people involved, of course. As Shae, actor Sibel Kikelli does harrowing work here: She’s both the betrayer and the betrayed, and her every line communicates a mix of sorrow, regret, rage, and raw terror. Tyrion, meanwhile, reaches the low point in a life filled with public humiliations. Now it’s his sexuality – the most private and intimate aspect of the physicality that’s gotten him mocked and shunned for decades – that’s put on display for the world to see, complete with pet names and pillow talk.

Simply put, it breaks him. Once again, the camera tells the tale: It circles like a vulture as actor Peter Dinklage swivels this way and that, turning his head over his shoulders to track down and berate the gazing, gawking eyes of the audience he’s forced to endure. So Tyrion plays to type, wishing death and destruction on the people who’d use something as noble as love against him. (That he did the same thing to Shae, calling her a whore in order to get her to leave town, is an irony unlikely to be lost on him.) Now he’s Richard III – a titanic figure, willing to embrace his infamy. Fuck the deal his dad and Jaime made; he’ll take his chances on a trial by combat once again. He’s gambling that his brother or Bronn will enable him to walk out of King’s Landing a free man. But the fury Dinklage pours into him makes his real goal clear: He wants to give his father, his sister, and all the nobles in the realm reason to fear. Throne room or no, you’re in his house now.

I reviewed Sunday’s episode of Game of Thrones for Rolling Stone, paying special attention to sets and staging.

“Mad Men” thoughts, Season Seven, Episode Five: “The Runaways”

May 12, 2014At the episode’s conclusion, issues of loyalty and command come to a head not once but twice. After a tipoff from Harry, Don crashes Lou and Jim Cutler’s meeting with the aptly named Commander cigarette brand execs from tobacco giant Phillip Morris. If the firm gets the gig, Don, who famously tore the cigarette companies a new one in the pages of the New York Times, has gotta go. (Which is precisely the idea—there’s Lou’s loyalty for you!) So Don sells his services almost exclusively with the vocabulary of power: The government built a gallows for Big Tobacco but Don “stayed the execution,” and even though he betrayed the cigarette companies before, why not “force me into your service” and score a bigger victory over your rivals in government and business alike? A master of the language of authority, Don can wield it, reject it, fight it, and submit to it in a single sales pitch.

Michael Ginsberg is not so lucky. Throughout his brief but memorable time on this show, he’s reacted to his circumstances like a man on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Even before he went all Dave Bowman about SC&P’s resident HAL-9000, he was shouting “I am become death!” about working in advertising at all. It came across like a neurotic quirk of ’60s Jewish comedians he’s likely based on—at least until we learned he may have been born in a concentration camp. That is how Michael Ginsberg understands authority. And when a computer—the ultimate unfeeling embodiment of cold command—takes over his break room, Ginsberg breaks. So did a lot of people, when confronted with a society and a government indifferent to whether they lived or died. The very fabric of Scout’s Honor is more than a joke to them. It’s a joke on them.

The 40 Best Cult TV Comedies Ever

May 8, 2014“31. ‘Mystery Science Theater 3000’

Sure, they did it out loud in front of a big screen (or at least their silhouettes did) back then while we do it now by livetweeting the latest episode of Scandal. But in a twist stranger than any of the countless B-movies they watched, MST3K – in which a human and two robots watched bad movies and made fun of them the whole time — basically became our culture. Not bad for a show that started out on a local Minneapolis TV station, though keeping the microscopically low budget and cosplayers-at-a-comic-con aesthetic was a brilliant move; the low-rent feel is part of the charm. The later schism between hosts Joel Hogdson and Mike Nelson has caused almost as much intra-nerd strife as Kirk/Picard or Edward/Jacob — still, we’ve all put our faith in Blast Hardcheese.”

I helped write a countdown of the greatest cult-tv comedy series ever for Rolling Stone. It was fun!

“Mad Men” thoughts, Season Seven, Episode Four: “The Monolith”

May 5, 2014Spending so much time in a space suffused with death causes Don to see the infernal when he contemplates the infinite. He confronts [computer salesman] Lloyd as Satan in short sleeves: “You talk like a friend, but you’re not. I know your name. No, you go by many names—I know who you are. You don’t need a campaign. You’ve got the best campaign since the dawn of time.” As one of Creative’s three heads, Don naturally sides with the Creator against the Enemy. Who cares about cataloging the stars, when you can dream of them?

But the task that returns Don from his stargate-in-a-bottle isn’t dreaming, it’s committing those dreams to paper. “He’s an exquisite copywriter, if nothing else,” Jim Cutler told Lou; it turns out “nothing else” is needed. What makes Don Don is what happens when he sits at a typewriter and starts click-click-clicking until he distills the infinity of ideas into 25 tags for Burger Chef. “Do the work, Don,” said Freddie Rumsen. All work and no play makes Don a dull boy, yeah, but a dull boy is still a human being. It’s doing the work that makes Don more than a machine.

I reviewed last night’s Kubric-scented Mad Men episode for Wired.

Sean & Julia on Poe & Porn

May 5, 2014What inspired you to make this Poe Porn (lol)?

Sean: Julia and I have a lot in common, and one of those things happened to be a fascination with this particular Poe story, which we’d both read at an impressionable age.

Julia: I felt like Sean’s script was such an effective interpolation of the original story because in a sense it wasn’t radical at all, its constituent elements are entirely native to the source material. There are hints of regret, of reluctance, almost tenderness, supporting the maniacal sadism. The meticulousness with which Montresor inflicts the final act of cruelty on his friend already carries an erotic undertone–maybe not all readers experience that, but Sean and I didn’t invent it.

Sean: In “The Cask of Amontillado” I recognized a link between the genres of horror and pornography. Both frequently rely on a sense of certainty for their visceral emotional impact: When you begin to read or watch a horror story, you know that a terrible thing will happen, and frequently so does the character to whom it’s going to happen. In pornography, as in sex generally, you know that when your partner begins touching you, you have entered into a process that will end with you briefly losing control of your own body, unable to think of anything but the pleasure your partner is effectively forcing you to experience at the expense of everything else. In both cases that certainty is magnetic to minds trapped in our unforgivingly inconstant and unpredictable world. Dread and eroticism are two sides of the same coin neither of us can stop flipping in the art we make or consume.

Julia: Right, I rarely respond to a sex scene that doesn’t have some foreboding attached to it. The sense that the world has stopped and what’s happening right now is the only thing that matters or exists is romantic, but it also feels like something on the verge of panic.

Sean: “The Cask of Amontillado” and Montresor’s revenge scheme both depend on that certainty — on Montresor letting Fortunato know exactly what’s happening to him, and exactly what will continue to happen to him until he dies. There just came a day when I wondered what would happen if Montresor’s mental circuit overloaded and that horrific mastery over another human being became erotic mastery over the same person. This was the result.

We hope to do more Poe-nography together, actually. We’ve been talking about “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

Julia: “The Pit and the Pendulum” seemed a little on the nose.

—Glory Hole In One: A NSFW Comic Book Review & Interview | Slutist

The marvelous writer/musician/dominatrix Hether Fortune interviewed me and Julia Gfrörer about In Pace Requiescat, our pornographic adaptation of/extrapolation from “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe, for Slutist.You can buy the comic here.

“Game of Thrones” thoughts, Season Four, Episode Five: “The First of His Name”

May 5, 2014Once again, we close out the episode beyond the Wall, with a sequence as cathartic as last week’s was horrific. Jon Snow and his merry men make short work of the mutineers at Craster’s Keep — and yeah, we all felt a little swell of way-too-invested-in-this-show pride considering how green those dudes were just a couple seasons ago. Though the dramatic visions of Jojen Reed and the telepathic powers of Bran Stark intrude on the imagery and plotting like such things rarely have before, it’s ultimately the fate of Craster’s daughter-wives that’s most moving as the episode draws to a close. Since the Night’s Watch turned a blind eye to Craster’s abuse of his wives for years before a gang of them tried their hand at it themselves (even a valuable hostage like Meera Reed was just one more potential victim to these men), the women refuse Jon Snow’s offer of so-called safety at Castle Black. They burn the keep and the bodies, and they go their own way. “Everywhere in the world, they hurt little girls,” Cersei had said. But not here. Not anymore.

A May Day thought

May 1, 2014Respecting creators’ rights is not about reasserting the magical aura of the Artist in opposition to the hoi polloi, it’s about defending the relationship between worker and the work produced. Creators’ rights are labor rights.

Living dead girl: “Dead Girl Shows,” “True Detective,” and a defense of “Twin Peaks”

May 1, 2014There’s a lot to think about in Alice Bolin’s essay “The Oldest Story: Toward a Theory of a Dead Girl Show” in the Los Angeles Review of Books. What starts as an insightful and often bleakly witty look at the strengths and weaknesses of Nic Pizzolatto’s True Detective falters when it unfairly conflates that entertaining but very deeply flawed show with David Lynch & Mark Frost’s vastly superior Twin Peaks.

“Just as for the murderers,” Bolin writes, “for the detectives in True Detective and Twin Peaks, the victim’s body is a neutral arena on which to work out male problems.” For True Detective this is, well, true. For all the show’s gestures in the direction of excoriating predation upon the less powerful by the more powerful, usually meaning upon girls by men, it’s ultimately a show that erased the very victims it purported to care for. The emotions of the male cops were our only window on their personhood and suffering.

By contrast, Twin Peaks brought us where Laura Palmer lived and forced us to keep looking at how she felt there. Indeed, Lynch made an entire prequel film for precisely that purpose (one that gives lie to the Bolin’s claim elsewhere in the essay that death prevents the Dead Girl from claiming the redemption available to the living males who investigate her death, but that’s neither here nor there). Unlike True Detective, where we as viewers are never separated from the focalizing influence of Marty, Rust, the two cops investigating them, and eventually the killer, the experiences of Laura, Maddy, and Donna were central to Twin Peaks, allowed to stand on their own, and devastating as such. Asseriting that “in Twin Peaks…the central characters are male authority figures” participates in the precise erasure the essay is decrying.

Moreover, the show worked rigorously to de-glamourize its presentation of rape and abuse. Even in the more explicit prequel film Fire Walk With Me, the sexual activities Laura initiates, though shown to be in some way sexy to her, are so because they represent crude and damaged attempts to reassert sexual agency in the face of years of horrific rape and abuse. Our glimpses of the actual rapes and assaults that take place are heartbreaking, soundtracked by screaming and sobs. The fallout for Laura, for her female classmates, for her mother — these are all chronicled unsparingly. This, and the unique and unforgivable violation represented by the identity of the killer, are what the show is about; the uncanny imagery and stunning filmmaking are intended to charge those elements, not the other way around.

Bolin also badly misreads the role of the supernatural on Twin Peaks — not just the Black Lodge and its murderous entities specifically but, I think, the nature and function of monsters in horror fiction generally. Citing the role of the demonic Bob in Laura’s murder, Bolin writes, “Externalizing the impulse to prey on young woman cleverly depicts it as both inevitable and beyond the control of men.” As evidence she cites a statement Agent Cooper makes to Sheriff Truman that the existence of supernatural evil beggars belief no more than the existence of the very human evil it helped enable. But in context, that line is intended to drive home the horror of wholly human abuse, not dismiss it. For one thing, countless male characters in Twin Peaks — Bobby, Leo, Ben Horne, the Renault brothers, Dr. Jacoby, the faraway editors of Flesh World — required no supernatural intervention whatsoever to commit their exploitative and misogynistic actions.

For another, monsters have since the dawn of time represented not just external but internal fears, our terror not just of the outside and unknown but of the impulses and excesses of mind and body we know all too well, because those minds and bodies are our own. I believe the idea that the killer bears no complicity for the killings because of the role of the supernatural isn’t even borne out by the text, but even if it were, the supernatural is not there to let male viewers off the hook in terms of their contemplation of the simultaneously universal and individualized nature of misogyny. It’s there to embody it.

The essay concludes by unfavorably comparing TD and TP to the more recent “Dead Girl show” Pretty Little Liars. It concludes:

What would seem to be Pretty Little Liars’s worst faults — its unwieldy plot, its lack of consistency, the culpability of so many characters — are actually instructive. Its creators have made a Dead Girl Show that is not about a journey instigated by a Dead Girl body toward existential knowledge, but the mess, the calamity, and the obscurity that are the consequences of misogyny.

This, of course, is an excellent description of Twin Peaks.

Andy Daly’s “Review” is secretly the antihero-TV satire you’ve been waiting for

May 1, 2014Comedian Andy Daly’s stand-up as different characters is amazing, but at first I wasn’t sure what to make of his Comedy Central show Review at all. He plays this really square TV host who “reviews” different life experiences: going to the prom, addiction, space travel, having a best friend, orgies, eating pancakes, all kinds of things. At first you think it’s gonna be this comedy in which someone makes a major production of doing things in a very stiff, social-anthropology, insider-playing-at-outsider way. Which is indeed the basic approach.

But what ACTUALLY happens is that instead of treating each “review” as a separate thing, there’s continuity between all of them. The magical comedy reset button you’d expect them to hit after, say, the character gets addicted to cocaine, overdoses, and goes to rehab, never gets hit. The experiences build one on top of another. So even though he never acknowledges it except in one brief fit of self-pity while eating an enormous stack of pancakes (don’t ask), you slowly watch him destroy his life and the lives of everyone around him. His marriage ends. People get killed. All under the rubric of this very high-concept mockumentary show.

In other words, this is a satire of New Golden Age of TV Drama antihero shows hiding in plain sight. It takes the basic “man ruins all he cares about in the name of something that makes him nominally freer and more powerful” structure of the genre and plays it for deliberate laughs. Instead of a meth empire or a mafia family or a double life, he commits his bad acts in the name of the television show that chronicles them. He’s Walter White, but without the sense that there’s anything tragic about him — he’s just an oblivious faux-smart buffoon. It’s a satire of the middle-class middle-aged white-male entitlement and privilege that all the big dramas treat as the stuff of life. And it’s unbelievably funny.

The season finale airs tonight, and in the meantime every episode is available in its entirety with no ad breaks for free on YouTube. You can watch the whole thing in the time it’d take you to watch a 2 1/2 hour movie. GO.

“Game of Thrones” thoughts extra: Cersei, Jaime, and Craster’s Keep

May 1, 2014I referenced this in my review a bit, but the Craster’s Keep sequence in the most recent Game of Thrones episode is The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, it’s Hostel, two of my favorite horror films of all time. (Texas Chain Saw is one of my favorite films of any kind, period.) The spectacle, the excess, the relentless primal-scream tone, it’s deliberate, it’s meant to be shattering, it’s meant to concretize the experience of cruelty and moral degeneracy. Under normal circumstances I’ve had responded quite favorably to that, I think, particularly as it segued into the supernatural/cosmic horror of the White Walkers. That too is a spectacle of a kind — the endlessly long takes in which you’re just rooted to the spot with a screaming infant in the cold as monsters gather to snuff out its life. Excruciating, and communicative in a way more subtle filmmaking can’t be.

The thing was, though, that the (mis)handling of the Cersei/Jaime scene the previous week, and potentially into this week depending on how you view the follow-up sequences, had thrown me for a loop, making it difficult for me to process the Craster’s Keep material the way I normally would have. What might normally have read as Salo-style forcing your face into the filth instead made me think that, for example, either some of the nudity or some of the on-screen visible rapes should have been elided.

Which tracks back to the Cersei/Jaime scene, which I believe to be a failure of filmmaking, not of morals or ethics. As a basic platform for discussion, I should note that I think the change from consensual to nonconsensual, if indeed that was the intention, is a valid choice. I don’t think it “ruins” Cersei or Jaime as characters, I don’t think it ruins their future arcs (which for the purposes of the show don’t even exist yet); I don’t think it’s inherently misogynist or reflective of misogynist thinking — I think it reflects the misogyny of the fictional society being chronicled. Be all that as it may.

Right, so. The more I think about it, the more I watch the episodes, the more interviews I read with the involved parties, the more I suspect one of two things took place. Possibility number one is that they tried to show a sex scene between two very fucked-up and violent people in which power exchange and the violation of taboo is a huge part of the sexual dynamic, but they screwed it up, and it came out as a rape scene. Because everyone involved was, well, involved, no one saw it. A secondary possibility is that while the writers intended the scene to be rape, the director and the two actors involved on the day read it and played it differently (there’s famously little background preparation done by the cast in terms of comparing notes with the books or with other characters’ storylines, so it’s not inconceivable), and the result is muddled and flawed. In neither case do I think the scene is reflective of a disgusting misconception that rape is okay, that sometimes no means yes, that it’s fun to insert rape scenes for no reason, or anything similarly depiction-as-endorsement rape-culture supportive. I think that while the apparently HBO-mandated use of nudity needlessly muddied the waters, the show has been as strong in its condemnatory presentation of this fictional world’s morally and practically disastrous institutionalized misogyny as the books. (I still prefer the books as a work, for whatever that’s worth.) If the scene failed it’s a failure of execution, not ethics.

But ultimately, using authorial intent — or textual absolutism, or adherence to a specific set of sociopolitical ideals, or the use of a favored set of aesthetic signifiers (in my case, my much beloved heads on sticks) — as a pass/fail metric is a fallacy when it comes to responding to art, an attempt to objectivize what is inherently subjective and prohibitively complex. So in the end what Benioff, Weiss, Cogman, Graves, MacLaren, Headey, and Coster-Waldau thought they were doing matters much less than the sum total of their work on screen. The text is everything and these are some thoughts about how I read it and why.

Oral history lesson

May 1, 2014A couple weeks ago Jessica Hopper published an oral history of Hole’s Live Through This, and it had been a very long time since I reacted to a work of criticism so intensely so quickly.

For one thing, speaking as a writer who’s done one in the past, this is an achievement in using the oral-history form to reveal information, rather than aid in cloaking it through self-mythologization. It’s so easy to do that with these things. Shit, it’s baked into the premise of the enterprise: Look at my proximity to all these people’s proximity to greatness!

But it’s not that Hopper doesn’t include all the choice nugs you’d want in an oral history — you know, anecdotes about meeting RuPaul while hammered at the SNL afterparty, differing accounts of how badly Courtney Love wanted to work with Butch Vig, etc. It’s that she treats it not just as a history of a cool thing, but as reporting on that thing. She digs into how the studio was selected, how the personnel came together, what the schedule was like. She digs into the rock climate at the time, the (limited) involvement of Billy Corgan and Kurt Cobain, the (profound) influence of Siamese Dream and Nevermind. She digs into drug use, who was doing what and when. She talks to band members, producers, label people. She lets Love hoist herself by her own petard when that’s called for, but she also lets her emerge, then and now, as someone who had a very clear artistic goal and worked, successfully, to achieve it. Inner torment and commercial ambitions and improved songwriting chops and a better rhythm section and working with a guitarist with little self-confidence and hiring skilled producers and developing a workday routine and navigating the demands of other prominent artists in the field with whom she was close — it all went in and that record came out, and Hopper gets it all down. I suppose she’s lucky that she got such a forthcoming group of interviewees, since god knows that’s rare, but luck’s a fundamental part of a good piece too.

I didn’t listen to Hole in the alt-’90s heyday; didn’t buy the “Yoko” nonsense either, that just didn’t seem to cut any more ice here than it does with actual Yoko. And there’s no way to be judgmental about Love as a parent without being more so about the one who isn’t there anymore at all, so I think I gave that a pass over the years as well. Point is I didn’t have much riding on reading this either way. But what a fascinating document of the making of a work of art, and what an inspiring example of how to write about art. It makes me want to work harder.