Optic Nerve #12

Adrian Tomine, writer/artist

Drawn and Quarterly, 2011

40 pages

$5.95

Buy it from D&Q

Read a preview at Boing Boing

Man, is this thing ever happy to be a comic book.

The format of a comic doesn’t matter to me a whole lot, unless the format in question is notably detrimental to the comic it houses. I like the idea of serial alternative comic book series mostly for the promise of seeing a lot of work from alternative cartoonists on a regular basis, but today that need is met by the web. (Which can’t meet all needs, to be sure — it doesn’t meet the need of retailers to have that kind of material showing up fresh every few months and consequently attracting a different clientele to the shops on Wednesdays, but that’s not my bailiwick.) But in Optic Nerve #12, Adrian Tomine reminded me what can make an alt-comic such an attractive and pleasurable way of packaging material, something not even the most well-stocked RSS reader can provide.

In addition to the usual letters page, its weirdly personal mix of praise and criticism as po-facedly selected as always, the issue consists of three comics. The first, “Hortisculpture,” feels like an homage to the apparently final two issues of the greatest of the alternative comic books, arguably the two best single alternative comic book issues by anyone: Dan Clowes’s Eightball #22 and #23. Like them, the story is constructed from individual self-contained strips, in this case a full “week”‘s worth: six black-and-white four-panel strips plus a full-color “Sunday” page, over and over till the end of the story. Said story recounts a family-man landscaper’s quixotic career detour into the world of contemporary art via his own unique blend of sculpture and horticlture, an unappreciated (arguably unappreciatable) hybrid his pursuit of which upends his life. As a crypto-autobiography it’s a corker — a keyed-up, hyperreal representation of the travails of Tomine’s chosen form of self-imposed artistic marginalization. It’s as engrossing to watch him work his way through as, say, Gabrielle Bell’s similar fictionalizations of her family life. (Plus it allows Tomine’s customary preoccupation with the intersection of race and romance a new, markedly less hostile environment in which to flower.) Things have gone a lot better for the cartoonist than the hortisculptor, to be sure — the former just received some of the best notices of his career for the wide release of the comics he made about his marriage to the mother of his kid, while our last glimpse of the latter is of he and his daughter gleefully smashing his work to smithereens — but the anxieties underlying the worst-case-scenario comic are obviously real, and really funny. And once again like Clowes, in Eightball #22 and later in Wilson, Tomine’s working with a much “cartoonier” style — a curvier line, bulbous noses, dot eyes, doughier physiques — that enjoyably invokes similar work from Sammy Harkham or Chuck Forsman. It feels right, somehow, to look at art like this on a staple-bound page.

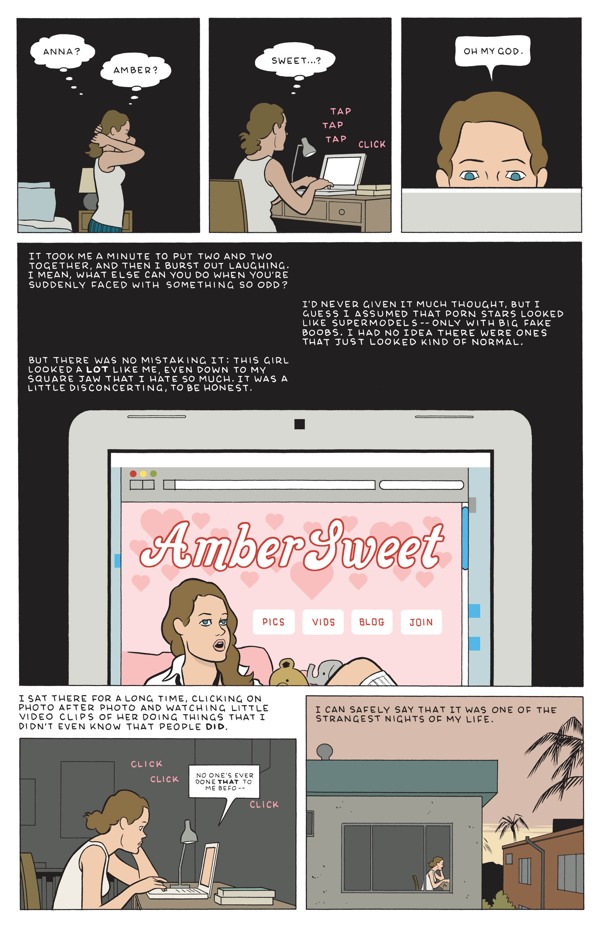

Next up is that staple of one-man anthology series, the reprint from some other anthology. In this case it’s Tomine’s “Amber Sweet” from the broadsheet-sized Kramers Ergot 7, attractively scaled down to the size of the floppy comic, its muted color scheme even more clearly centered around the nutmeg-colored hair of the young woman who discovers she’s the spitting image of the titular porn star. “Sweet” is fascinating to me in that it’s about how unsexy sex can be: our protagonist’s love life, and more besides, is basically destroyed by her resemblance to Amber, a resemblance the men in her life are either daunted by or way too into. Tomine’s perhaps uniquely suited to explore this plight: his cartooning is as sexy as it gets, I’ve always found — his line elegant, his compositions enticingly icy, his character designs very attractive, from Amber and her never-named doppelganger on down — but his work relentlessly cuts against that with the awkwardness and selfishness of his characters. Here we see a beautiful girl who looks like another beautiful girl who makes her living by taking her clothes off and having sex have sex herself as drawn by one of alternative comics’ great unsung sensualists, but the story denies us the pleasure on every possible level. It’s a blast to watch Tomine so successfully negotiate that obstacle course on the way to the story’s knockout ending, a beautiful and satisfying opening-up of the story’s emotional claustrophobia.

The third and final strip — two pages, 20-panel grids — is Tomine’s Lament, pretty much, a self-effacing mock-autobiographical strip about Tomine as “The Last Pamphleteer,” his adherence to the alt-comic format earning him the laughter of his peers and the indifference of his audience. And here, perhaps, he’s trying a little too hard. Throwing “tweet” into sneer quotes as if the term is an affectation instead of just, y’know, email or website; saying things like “I even liked it when the artist was obviously just trying to fill a few extra pages, and you’d get a pointless, dashed-off autobio strip or something!”, as if both he and we didn’t notice that he had to cram this thing onto the inside back cover to get it to fit; using D&Q publicist Peggy Burns as an antagonist, as if he weren’t still core Drawn and Quarterly artist Adrian Tomine; setting up Anders Nilsen and Kate Beaton as models for the new book-driven publishing model, as if they too weren’t primarily collecting work they published in smaller chunks elsewhere…He doth protest too much, and while the result is amusing, who needs it? He’s Adrian Tomine. He writes great and draws great and is as good at using his chosen format as anyone else is at using theirs. That’s all you need.

Tags: Adrian Tomine, comics, comics reviews, Comics Time, Drawn and Quarterly, Optic Nerve, reviews

Uh: isn’t the point of Amber Sweets that she’s lying to the guy? I thought that was the whole point of the ending. It doesn’t sound like you read it that way, though.

You mean that she IS Amber Sweet, and this whole story is just a lie so that the guy won’t think she used to be a porn star? That’s a pretty marvelous idea, but no, I don’t read it that way. I mean, the lie would only work if “Amber Sweet” had retired, which would be something she’d have mentioned near the end of the story if it were the case. Then again, perhaps that’s what she’s getting at with “I don’t think about Amber Sweet much these days, but I honestly hope she’s happy and maybe doing something better with her life.”

I should add, I suppose, that personally I like the idea of a story of a person whose life was messed up because she looks like a porn star more than I like the idea of a story of an ex-porn star with Walter White-level lying abilities. The former’s something I’d never thought of before, the latter is porn star tries to leave the past behind, which is very familiar and distinguished here only by the trick ending, if that’s in fact what it is.

I’m sorry– yes, that’s exactly what I meant. I just realized I never said so. That was rude of me; my apologies.

Not rude at all! It was clear what you meant.

You may both be right: The story is true, but it’s Amber who tells it. When they met, Not-Amber told her everything, after all, at Amber’s urging. So maybe that’s what Amber was apologizing for: leaving all her bad karma with Not-Amber and making Not-Amber’s story her own.

The fact that the story works for all three perspectives is pretty cool, though.