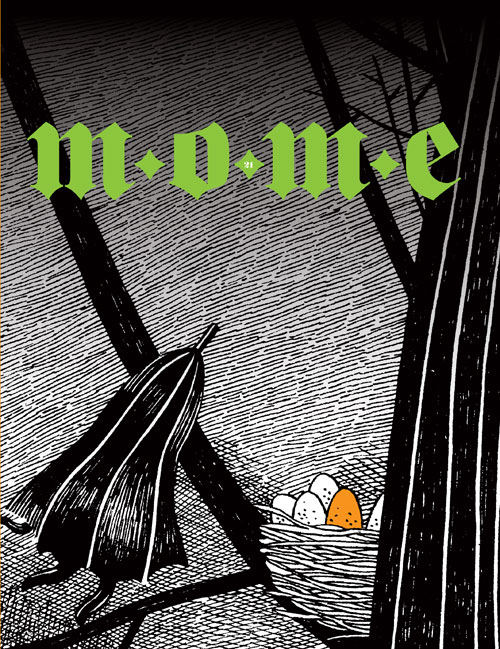

Mome Vol. 21: Winter 2011

Sergio Ponchione, The Partridge in the Pear Tree, Josh Simmons, Dash Shaw, Steven Weissman, Kurt Wolfgang, Sara Edward-Corbett, Nicolas Mahler, Tom Kaczynski,

Josh Simmons, Jon Adams, Nate Neal, T. Edward Bak, Michael Jada, Derek Van Gieson, Nick Thorburn, Lilli Carré, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds, editor

Fantagraphics, 2011

112 pages

$14.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

It was the best of Momes, it was the worst of Momes. Alright, that’s not quite accurate, and not quite fair, either. But this unwittingly penultimate issue of Fantagraphics’ long-running alternative-comics anthology — page for page the longest-running such enterprise in American history! — is a hit-or-miss affair in the mighty Mome manner. In the miss column you can place Sergio Ponchione’s bombastic, cartoony fantasy about an imaginary childhood friend brought to life; there’s really not much more to it than that description would indicate. Ditto Kurt Wolfgang’s next “Nothing Eve” chapter, which continues to work the “people still act pretty much the same even though the end of the world is coming” buttons it’s been mashing since issue #1. T. Edward Bak’s “Wild Man” remains awkwardly paced due to its split-up narrative captions; Nicolas Mahler’s autobio strip remains of limited interest to people not Nicolas Mahler; Lilli Carré’s contribution is nicely colored in reds and blues but otherwise insubstantial.

A few contributions are both hit and miss at once. Sara Edward-Corbett’s near-wordless reverie involving inanimate objects romping around the outside of a house comes across more inscrutable than mysterious, but at the same time her crosshatching and linework are an absolute marvel, and she’s playing with forms (and with form) in a fashion reminiscent of John Hankiewicz, if not as successful. Steven Weissman’s deadpan “Barack Hussein Obama” strips fall flat when they merely parody the rhythms of four-panel gag comics, but spring to surreal and oddly scathing life when he injects a healthy dose of the sinister supernatural into them. I’ve never quite cottoned to the way Jon Adams’s razor-thin line and labored-over character renderings sit against the large white expanses of his pages, and his writing feels overwrought to me, but he does give his blackly humorous tale of a hunting expedition gone bad a laugh-out-loud visual punchline. And Nate Neal’s caveman morality play makes much better use of his meaty cartooning than his lukewarm slice-of-lifers do, though the conceit of gibberish dialogue from the cavepeople conceals more than it illuminates.

So that leaves the hits, and they’re strong enough to make the book worth checking out. Dash Shaw continues his seemingly ongoing series of adaptations of “reality” programming, this time an excerpt from a making-of documentary about Jurassic Park; he has a really sharp and off-kilter eye for people observing and commenting on their own behavior for a camera, and his transition from talking heads to full documentary “footage” is a gleeful one. Nick Thorburn’s take on Benjamin Franklin, a first-person monologue in which Ben lets us in on a dirty little secret, is anachronistically absurd (“In Seventeen-Sumthin’-Er-Other, right before I invented electricity and just after I’d sired my illegitimate son, I received an e-mail from Lord Sandwich about comin’ to London to take part in this new secret society known as ‘The Hellfire Club.'”) and very funny, with a great undergroundy character design for Franklin himself. Derek Van Gieson’s murky World War II period piece continues to stun from page to page. Tom Kaczynski examines home ownership during terminal-stage capitalism as only he can, casting it as a catalyst for powerful erotic and apocalyptic impulses and proving himself once again to be one of the most stealthily sexy cartoonists working today. “Stealthy” isn’t a word I’d use for Josh Simmons, but he doesn’t need it: His weird psychedelic fantasia on racism “The White Rhinoceros” is as bold and bulldozing as the giant slugs who stampede across its pages, and the elliptically concluded short story “Mutant” ends with an image of an enraged creature in the form of a human female, her nude body shadowed but covered in glistening sweat, that may as well symbolize the workings of Simmons’s entire brain. You gotta take the rough to find the diamonds.

Tags: comics, comics reviews, Comics Time, Dash Shaw, Derek Van Gieson, Eric Reynolds, Fantagraphics, Jon Adams, Josh Simmons, Kurt Wolfgang, Lilli Carré, Michael Jada, Mome, Nate Neal, Nick Thorburn, Nicolas Mahler, reviews, Sara Edward-Corbett, Sergio Ponchione, Steven Weissman, T. Edward Bak, The Partridge in the Pear Tree, Tom Kaczynski