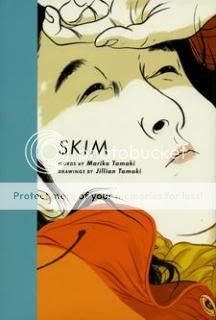

Skim

Mariko Tamaki, writer

Jillian Tamaki, artist

Groundwood, 2008

140 pages, hardcover

$18.95

The story of a teenage outcast’s traumatic, illicit first love, Skim impressed me with what it chose to show and what it chose to hide. On the show side of the ledger, first of all, it’s a book about a teenage Wiccan lesbian and about suicide, and it really doesn’t skimp on any of that. There are rituals, there’s a love story, there’s cursing out the wazoo, and teenagers die. It’s an article in a local newspaper about What Our Children Are Reading waiting to happen. In that sense, even though it’s very much a Young Adult book, it felt to me less like something created to be maximally appealing and accessible to a YA readership and more like something created the way we like to imagine all good comics are created: A writer and/or an artist had an idea and committed it to paper, full stop. Ballsy.

Also in the “show” column, there are the stylistic filigrees and flourishes of Jillian Tamaki’s art. Her figurework is really singular and memorable, most prominently: There’s a shot early on of a hallway full of Catholic high school girls, the plaid of their skirts more a suggestion of motion than a pattern on fabric, that is simply swoonworthy if ever you’ve swooned over a hallway full of Catholic high school girls. Main character Kim “Skim” Cameron’s “otherness” is suggested with the clever visual shorthand of making her face look like someone that stepped out of a classical Japanese portrait. Ms. Archer is every bohemian art or English teacher you’ve ever crushed on, swirling around under yards of fabric and hair. Suicide-haunted Katie Matthews’s face is a pinched little scowl, not depressed so much as enraged. Even the cowlick epidemic that plagues the hair of what seems like a solid 50% of the characters comes across as an endearing tic rather than a goof. It’s all very cleverly done.

Then there’s the equally clever “hide” column. I fairly marveled at just how much was left unsaid or performed offstage. Why on earth would Ms. Archer do what she did? Though we get a lot on the damage she did, and can infer how she chooses to deal with that damage, the damage that caused her to do what she did is unexplored. Actually, so is…what she did itself. There are hints, there’s a fleeting glimpse, but we never learn how far things went, what was done, what was said. This is where the wise choice to make Skim such an unreliable narrator comes into play. She’s constantly crossing out and rewriting her narration, and we establish early on that she’s willing and able to skip over major, major events if she doesn’t feel comfortable discussing them. We’re never able to trust that she’s giving us the whole picture, and that lack of trust is the structuring absence around which the story and our understanding of it is built. This in turn is reflected in the rumors and half-truths and lies and gossip that keep buzzing in the background, and in the lack of candor between Skim and her supposed best friend Lisa…it’s really a book about hiding, now that I think of it. The villains of the piece, such as they are, are villains precisely because they make such a show of everything. Even the climactic happy ending is presented to us as obliquely as possible. The moral of the story is that private lives are private, and you offer access to them at both your great pleasure and your great peril.

Tags: comics, comics reviews, Comics Time, reviews