Archive for April 15, 2008

Carnival of souls

April 15, 2008* It’s official: The Lost season finale has been expanded to two hours.

* Meanwhile, it should be noted that as much as I dislike the “theory” school of Lost fandom, it’s one that is actively headmastered by the show’s creators.

* Now this is what I’m talkin’ ’bout: The tandem comicsbloggers at Thought Balloonists tackle Junji Ito’s horror masterpiece Uzumaki.

First up is Craig Fischer, who to my surprise looks at the series through the lens of three texts that were key to my senior essay on horror from college: Linda Williams’s “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre and Excess,” H.P. Lovecraft’s Supernatural Horror in Literature, and Noel Carroll’s The Philosophy of Horror. (Fischer misses the way Williams fudges her character/viewer physical-response chart for horror, but he’s forgiven.) His review is laden with deliciously debatable quotes about horror:

I think Uzumaki is effective at unsettling readers like me because of its fidelity to the general traits of the horror genre. On the most elemental level, the purpose of horror is to impart fear and nausea, and Uzumaki has that effect on me. Horror is the genre that raises goosebumps, that makes the hair on the back of your neck stand up.[…] For me, Uzumaki works as horror because its hybrid monsters and piles of spiral flesh violate enough natural, cognitive categories to make me sick.

Charles Hatfield’s follow-up focuses on the series’ self-reflexive theme of obsession and repetition. He also takes issue with two aspects of the story I consider features, not bugs: The characters’ comparatively blasé reaction to the horrific goings-on (I take it as a sort of “horror realist” approach) and the failure of the early chapters to cohere into a narrative (as Curt Purcell and I agree, side-stepping Noel Carroll’s “complex discovery plot” is no vice). Regardless, both Hatfield and Fischer’s posts are must-reads for fans of the comic and the genre.

* CRwM of And Now the Screaming Starts gives the film version of The Ruins a rave review, which is interesting because he argues that the “distillation” of the novel that so bothered me is in fact the key to making a successful film of the story. I might agree that it’s the key to making a film of the story, period; successful? Not so much.

* From the sublime to the ridiculous: This Guardian thinkpiece by John Patterson about how American horror filmmakers really ought to be concentrating more on how awful America is has got to be the nadir of the inescapable “I enjoy horror movies to the extent that they are allegories about political issues I don’t care for” meme among mainstream critics. Look, you don’t even have to disagree with the political premise of such critics (and while Patterson gets a little ridiculous and sloppy with his points of comparison, and also so grossly misreads Hostel that he pretty much invalidates himself as a critic, I’m guessing I do indeed agree with him on the underlying issues). It’s simply a question of whether or not sociopolitical allegory is either a necessary or sufficient component of good horror. If neither, then this unrelenting focus on it would seem to me to be a colossal misallocation of critical resources, akin to every single critic focusing on whether the monster’s teeth or killer’s chainsaw should have been more obviously penis-like. (Via Jason Adams.)

* My buddy Patrick Carone interviewed Gillian Anderson for Maxim, resulting in vague statements about the second X-Files movie and hotsy-totsy pictures that will likely remind you of small hours spent alone with the Internet ten years ago. You will then feel old and sad. (Also via Jason Adams, who will need to substitute Duchovny into this equation to reach this conclusion.)

* Battlestar Galactica mastermind Ron Moore will be helming a new sci-fi show called Virtuality, based on an idea by ABC’s axed early Lost proponent and “previously on Lost” voice Lloyd Braun. The description sounds intriguing. (Via my pal Sophie.)

* I’ve gotta file this one away for now, but the great Jon Hastings reviews M. Night Shyamalan’s much-maligned The Lady in the Water. I know it’s inexcusable that I haven’t seen it given that my affinity for Shyamalan’s films is inversely proportionate to that of the public at large (my ranking would go The Village, Unbreakable, Signs, The Sixth Sense).

Carnival of souls

April 14, 2008* The big news today, for me, is that Midnight Meat Train may yet get a theatrical release in the U.S. If it’s one of these “coming soon to a theater near you, provided you are near Tampa, Florida” deals, I’m breaking out the meat tenderizer.

* The other big news today is that Phoebe Gloeckner, one of the four or five best living cartoonists, has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to complete work on her years-in-the-making graphic novel about the mass murder of women in Juarez, Mexico. It does indeed sound like she’ll be using the digital technique I noticed a while back.

* My long-distance love affair with gaming continues: Joystick Divison’s Gary Hodges presents the Top 5 Most Unforgivable Video Game Enemies–not bosses, mind you, but the little pissants who made a level or game impossible to beat. Fucking Bald Bull, man.

* This Ernest Hemingway quote reminds me a bit of Bruce Baugh’s contention that mainstream critics have it backwards when addressing monsters in horror movies:

“No good book has ever been written that has in it symbols arrived at beforehand and stuck in,” says Hemingway. “That kind of symbol sticks out like raisins in raisin bread. Raisin bread is all right, but plain bread is better.” He opens two bottles of beer and continues: “I tried to make a real old man, a real boy, a real sea and a real fish and real sharks. But if I made them good and true enough they would mean many things. The hardest thing is to make something really true and sometimes truer than true.”

Comics Time: Mattie & Dodi

April 14, 2008Mattie & Dodi

Eleanor Davis, writer/artist

self-published, 2006

40 pages

$5

Buy it from Little House when its shop re-opens in June

This one didn’t quite do it for me. Partially I think it’s because Davis’s relatively realist story this time around, about a working-class woman who’s forced to take care of her elderly, bed-ridden grandfather and her very young and withdrawn little sister, lacks a certain level of mystery compared to the fables and fantasies I’m more familiar with from her. The problem is that Davis tries to apply some of the same storytelling techniques here that she uses in her fantasy stories–mysteriously silent characters, long wordless stretches, a touch of the monstrous (in the form of the moaning grandfather), matter-of-fact nudity–and they end up overwhelming any sense that this is real life carefully observed. (She isn’t helped by the hard-to-swallow obliviousness with which she imbues her main character.) Her cartooning is as strong as ever, with dynamic figures and an at times stunning selection of body language for her characters, but an overuse of zip-a-tone, strangely inorganic lettering and slightly over-animated facial expressions push it just a bit into slickness. It’s funny, I remember reading in Gary Groth’s interview with Davis in Mome that this was the comic that really made him sit up and take notice, but for me it feels like a detour from the more fruitful avenues of expression she’s pursued before and since.

Surf Nazis Must Die: The Musical!

April 13, 2008Isn’t that something you could totally see happening on Broadway today?

Extraordinarily brief carnival of souls

April 12, 2008* More hotness from Becky Cloonan:

* Quote of the day:

…I do worry that the series will feel such a need to send all of its plot threads rushing to their conclusions that it will abandon some of the more lyrical and human moments that gave the series such power in its first three seasons.

—Todd VanDerWerff on Battlestar Galactica

* Speaking of BSG, Jim Hanley HENLEY WITH TWO E’S and his commenters have a worthwhile discussion of the most recent episode going on too.

And what rough blogosphere, its hour come round at last, slouches toward Bethlehem to be born?

April 12, 2008I don’t know how I missed this–sometimes I think my RSS reader gets a little lazy now and then, or is maybe just in the vanguard of the machines’ war on humanity and this is its first tentative steps toward full-scale slaughter–but Curt Purcell added another post to the ongoing discussion about whether a more cohesive horror blogosphere would be a good thing, and whether the kind of big-deal linkblog that might help create such a blogosphere could also keep it on its best behavior. My instinct was that no, it couldn’t, not really: at best it could lead by example (which is no small feat, to be sure), and at worst it would simply be one less jerkwad blog.

Curt points out something that hadn’t even occurred to me: Given such a linkblog’s ability to generate traffic for the sites it links to and attention for the ideas on those sites, by choosing to focus on better-behaved (or just qualitatively better) blogs it could indeed help shape the discourse. That’s an excellent point, and I’m sure it would work in that way.

But then again (and uh-oh, here comes the Eeyore in me again), it would only work on blogs that were in it for the traffic and attention, which (while I can’t read anyone’s minds) I would imagine would be the blogs most deeply prone to cattiness, dogmatism, and other negative traits that don’t begin with domestic animals. That kind of thing would be tough to shake.

My guess is that real quality blogging comes from a “blog gratia blogis” mentality. I know Curt frequently says he wants to reach as wide an audience as possible, But I can’t help but feel that even if his audience consisted solely of googlebots and people who screwed up an “austin powers groovy baby” search, he’d still be rolling merrily along, blogging about Nazisploitation and whatnot. That’s what makes his blog great, and the kinds of folks who tailor their blogging to make themselves more acceptable to linkfarms are probably not so hot to begin with.

All that being said, I really have no idea why I’m being such a gloomy gus about all this when I would be genuinely happy to see a horror blogosphere develop, where more voices interacted and more people were around to hear those voices. (Though I must say I’m pleased with the sites I regularly visit right now.) I hope I’m totally wrong about all of this stuff!

Well, now I’m curious as to what Curt thinks about my other, less personality-driven quibble: the inherent difficulty in creating a cohesive blogosphere around a genre rather than a medium. I hope he posts on it…

Carnival of souls: special theoretical edition

April 11, 2008* This EW set-visit article on Lost by their irritating, fanboy-CW-reinforcing Island correspondent Jeff Jensen is packed with mild spoilers of the who-gets-a-flashback variety, but it’s also got some interesting bits regarding how the cast and crew’s perception of the show has changed since it cemented its 48-episode endgame. You pays your money and you takes your choice. (Via Jim Treacher.)

* Speaking of Lost, for whatever reason, it’s only been this season that I’ve reached critical mass with obsessive theory-spouting Lost fandom, and here’s why: It’s a total waste of time. Trying to predict what the show is “about” based on the information we have now presupposes that nothing that happens in the remaining two and a half seasons will alter or add to that information. Given the history of the show, and how many layers it adds to its mythos season after season after season, that’s a patently ridiculous notion. Trying to “explain” what’s going on now is like finding a bunch of pieces of a DIY Ikea furniture item and putting together a nice sturdy table, but then turning around and discovering like 60 more pieces and realizing it was supposed to be a sectional sofa. And that’s not even getting into the fact that these cockamamie theories almost always a) assert as fact suppositions with no roots anywhere but the theorizer’s mind (“given that the Island is stuck in 1996…”); b) completely lack any kind of character-based/emotional component, which is the whole point of the show, not whether the Monster is made of nanotechnology.

* Bruce Baugh hated, hated, hated the ending of Frank Darabont’s The Mist. In a separate post he uses the film’s Mrs. Carmody as a springboard for a call for more Scripturally accurate fanatics. For real, they could have done something rooted in the millennialist brand of evangelical Protestantism that’s made the Left Behind series a hit, and instead they coughed up a muddled cliché.

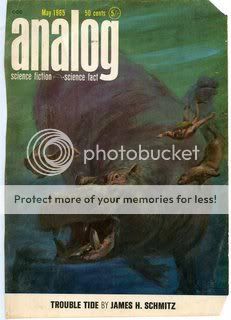

* This in-depth LA Times article on the long strange trip of the giant-shark movie Meg says there’s still some hope it’ll get made. (Via Bloody Disgusting.) I’m almost positive the eventual film will be very, very bad, but the water monster lover in me would be remiss not to show the totally bitchin’ promo image:

* I love how Paul Pope’s art looks more and more like elaborate cursive handwriting.

* Hey, Renee French has a blog! (Via Brian Heater.)

* Hotness from Becky Cloonan:

* Custom-made steampunk Star Wars action figures. Wowsers. (Via Topless Robot.)

* This week’s Horror Roundtable is about our favorite horror quote. With sexy results!

* Finally, “Hey Trash, what did Old Lady Clinton say when you torched her campaign headquarters?”

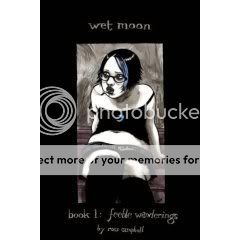

Comics Time: Wet Moon Book 1: Feeble Wanderings

April 11, 2008Wet Moon Book 1: Feeble Wanderings

Ross Campbell, writer/artist

Oni Press, December 2004

172 pages

$14.95

I’d imagine your tolerance for this book will vary proportionately to your tolerance for goth culture, because it’s definitely about goths. There are a lot of piercings and unusual hairstyles and ripped stockings and purses with little batwings sewn on them. But this strange, slow story about a group of kids at either the Savannah College of Art and Design or a fictional facsimile thereof isn’t your usual po-faced every-day-is-Halloween goth artifact. There’s a sadness and a weakness and a feebleness to everyone’s presentation of themselves as Goths, a recognition that this identity is the result of chipping away at certain surface characteristics until the desired result is achieved but that there can still be any number of chinks in the armor. Cleo and her friends/enemies more or less live in squalor, with pizza boxes and bags of chips and cockroaches strewn hither and yon. They make much of their bodily functions. They always look kind of tired and sickly. None of this is in the glamorous way that goths are supposed to work, either. Indeed the only character who truly appears to have perfected a seamless goth look and lifestyle is treated almost like an alien. And humor deflates the pretension on several occasions (what’s up, punch to the boobs?).

What is glamorous about the book is its recreation of that sense of languid, sexy ennui-bordering-on-mania that afflicts certain types of people in college. Laziness so profound it becomes almost sensual, a constant unspoken sizing-up of your fellow young people as sexual objects, a feeling that, despite being surrounded by like-minded individuals in a setting expressly designed to stimulate the exchange of ideas, you’re alone with your thoughts. This is essentially the storyline, but it’s best expressed through Campbell’s art itself. His women are extremely sexy in the way his lush line sort of idealizes their imperfections, and his dudes ain’t so shabby either, but they all have this slightly slackjawed, tired-eyed look of being dazed. Campbell frequently frames them awkwardly within their panels, using the surrounding space to suggest that they’re always a little lost, which is sort of the point.

Carnival of souls

April 10, 2008* Goddammit: Greg “Wolf Creek” McLean’s killer-crocodile movie Rogue‘s release by the Weinsteins is so limited…

How limited is it?

…it’s so limited, it’s not even being screened in New York Fuckin’ City! (Via the suitably outraged Jason Adams.) Truly it seems like there’s a neverending litany of bad news for horror projects dear to the hearts of us in the horror blogosphere, from Rogue to Cowboys for Christ to All the Boys Love Mandy Lane to The Midnight Meat Train to the Hellraiser remake. And it’s not exactly like Doomsday or The Ruins set the box office on fire, either.

* Here’s your unintentionally all-too-accurate quote of the day–Brad Meltzer on Justice League of America #150:

I was eight years old and it had Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and the rest all trapped in this intricate (remember, I was eight) villain deathtrap. Seeing all those superheroes together in one place set my eyes on fire. My addiction was born right there. To this very day, I treasure the idea that you can have a group of friends who will always be there to catch you. Why else would I spend the next 30 years fighting to get right back to that exact same space?

Emphasis mine, although Meltzer’s career to date is probably emphasis enough. (Via Tom Spurgeon.)

* And while I’m feeling uncharacteristically grumpy: Though I am indeed kind of hostile to the Meltzerian “gussying up your childhood favorites with Seriousness so you can keep loving them without being embarrassed” school of superherodom, at this point I’m starting to prefer it to creators of children’s entertainment product browbeating people about their weekly half-hour licensing showcase.

* I’m being slightly facetious by saying that a proper 50 Greatest Comedy Sketches of All Time list should contain 50 Monty Python sketches, but only slightly. Actually, I do love The State quite passionately and have always been amazed at how well their stuff holds up given how much of it parodied ’90s alternative youth culture in some way. And the SNL sketches they selected were pretty awesome, particularly Bass-O-Matic and the Chase/Pryor thing. But no Upper-Class Twit of the Year? Nigel, please. (Via Andrew Sullivan.)

* You know what’s funny? A few months ago I realized that while I may like individual albums by, say, Soundgarden or Alice in Chains better than any one album by Stone Temple Pilots, I like more Stone Temple Pilots records than Soundgarden or Alice in Chains or Pearl Jam records, and they’re only slightly outpaced by Nirvana (depending on how you count live albums and odds’n’sodds collections) and Smashing Pumpkins. They were actually pretty terrific and unpredictable songwriters, their first three albums are all solid listens from beginning to end and full of weirdness, they had Jawbox open for them when I saw them at Jones Beach way back when. In other words I like them more than many of the much “cooler,” more credible grunge bands–to my credit this was one time when I never pretended otherwise; I always liked them and was pretty unabashed about it–so it’s nice to see a full-scale, early-Weezer-esque reevaluation of the band going on. (Via Matthew Perpetua.)

* Here’s a pleasant little story about a woman who found a skeleton in her late mother’s closet–literally. Well, more of a decomposing corpse of the mother’s missing housemate, wrapped in plastic, but that doesn’t have that same ring to it.

* The indispensable Aeron at Monster Brains reports that there are Mat Brinkman prints for sale at PictureBox Inc.’s website (which is down at the moment, but maybe you can get there).

* Finally, via my pal David “The Face of Evil” Paggi: Can you beat this gallery of posters for ’60s and ’70s porno flicks? I submit to you that the answer is no, you cannot.

Carnival of souls

April 9, 2008* Another episode of Lost this season! I’m not even gonna pretend this doesn’t excite me greatly. (Via The Tail Section.)

* Bruce Baugh takes on Cloverfield in a pair of excellent posts. First, he focuses on how the good stuff was quite good but the bad stuff was not just bad but avoidable, which is dead on; he also has some insightful things to say about why 9/11-esque imagery is going to be showing up in disaster movies simply by default, and about a missed opportunity for the otherwise great creature design. (Meanwhile, check the very active comment thread for a Blair Witch bash-fest, and then click here to find out why they’re all wrong.) Second, he focuses on mainstream critics of monster movies and their “allegory or bust” approach to analyzing the films; Bruce wonders why the monsters aren’t first and foremost considered for what they are and what they do within the world of the film, and then considered for whether what they are and what they do is reminiscent of something going on in our world. (There’s a useful comment thread on this one too.)

* In a thoughtful review, Jason Adams echoes my take on The Ruins: Strong performances and memorable horror imagery undercut by rushed pacing and a loss of tension. He also points out something I forgot, which is that the time frame for the events of the story is shortened considerably not just before we get to the ruins, but after. He’s reserving final judgment until he gets a second viewing free from annoying audience members, though.

* Jason also runs down five of his favorite things from the season premiere of Battlestar Galactica. I’ve gotten the impression that people are classifying it as “good but not great,” and I would actually lean toward great. Granted, I was a little taken aback by the way (as Jim Henley astutely noted) the sci-fi/mythos aspects were foregrounded as opposed to the whole “human drama in a sci-fi setting”–I mean, they changed the intro from describing the basic premise to a more or less context-free description of a particular dangling plot thread, even. But from the cinematography and the performances on down–is there a better ongoing performance on television than James Callis’s?–I was constantly reminded what a great show this is by this episode. I mean, at varying times three or four of the main characters looked/look like they could be in the process of getting killed, and I believed in it every single time. That to me is a signal of great television.

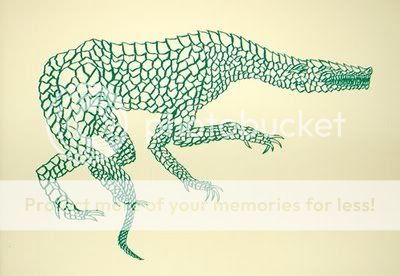

* Art show, part one: Daybreak cartoonist Brian Ralph is cleaning out his morgue and putting some killer pulp covers on display. This, uh, unique water monster struck a chord with me, as you might have guessed:

Giant hippos!

* Art show, part two: The Blot cartoonist Tom Neely has another weekly comic strip up and it begins like this:

* Art show, part three: Aeron at Monster Brains digs up another awe-inspiring Hieronymus Bosch knockoff, Herri met de Bles’ “The Inferno”–here’s a glimpse:

Comics Time: Jessica Farm Vol. 1

April 9, 2008Jessica Farm Vol. 1

Josh Simmons, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, April 2008

100 pages

$14.95

It’s a truism to say that comics have an unlimited special effects budget, thus casting their unfettered nature with regards to other narrative arts like film and television as primarily rooted in spectacle. But that sky’s-the-limit difference can be a formal one as well. With few if any physical or logistical constraints on an ongoing creator-owned comic’s length–particularly during this Internet Age–the ways in which stories are told may be similarly stretched. Any artist with a preexisting propensity for rambling, discursive narratives will find this limitlessness to be right in their wheelhouse.

No one seems to be stepping up to this plate with more determination than Josh Simmons, the underground-informed cartoonist behind many gleefully vulgar minis and anthology contributions who really exploded into comics-cognoscenti consciousness with his relentlessly bleak, wordless survival-horror graphic novel House last year. Jessica Farm Vol. 1 is the initial fruition of a project he’s apparently had simmering for eight years, a projected 600-page graphic novel drawn one page per month and released in 96-page installments every eight years until its completion in the year 2050. With Jessica Farm, Simmons has created a comics-reading experience where getting there isn’t half the fun–it is, by definition and at least for the next half-century or so, all the fun.

Is it fun? The answer is a qualified yes. For starters, Simmons tackles the erotic far more directly than any other cartoonists of his generation that I can think of, excepting Hans Rickheit I suppose–certainly more directly than anyone else with his Fantagraphics-granted level of exposure. The parts of this volume I’ll remember most vividly involve the titular teen (?) grabbing other male characters by the cock on more than one occasion, an earthy and erotically matter-of-fact gesture. While character design does not strike me as Simmons’s strong suit, he does give Jessica a winsome jolie-laide beauty, with wide eyes and sensually ropy tresses. And he really tapdances along the line that separates sexy from smutty from potty-humor in his depiction of his characters’ bodies. When we catch a glimpse of Jessica’s pudenda sticking out slightly from between her legs as we see her shower from behind, or when the mute, naked Mr. Sugarcock seasons her soup by dipping his balls in it Louie-from-The-State-style, or when Sugarcock’s full-tilt sprinting is indicated by his namesake member flopping like a windsock in the opposite direction, the sight is intimate, titillating and discomfiting all at once.

Indeed Simmons excels as an artist of human physicality. Fans of his memorably gruesome Batman pastiche will no doubt be delighted to find that comic’s thoughtful illustration of the body at work echoed throughout Jessica Farm, from watching tiny little people clamber up stairs that are each twice their height to the many shots of Jessica diving or pole-sliding through the many floors of her seemingly enchanted home. Depicting the cavernous and claustrophic contours of that home and other environments by moving his characters through them is another great strength of Simmons’s cartooning, and the scenes in which Jessica and her alternately adorable and threatening companions wend their way through the house’s darkened corridors no doubt contain within them the seeds of House, the artist’s full-length exploration of exploring.

The problem with this experiment, I suppose, is one of its methodology. The attention-getting publishing schedule is no doubt what made you aware of the book in the first place, and in terms of sounding completely awesome, hey, mission accomplished. But once you hit page 96 and realize that it’ll be another eight years before a subsequent volume provides you with a continuation–and more importantly, a context for–what you’ve just read, the bloom fades off that rose in a hurry. As I was getting at before, the format lends itself perfectly to a peripatetic story in which Jessica, Alice- (or Odysseus)-like, has a variety of surreal encounters. But as Alan Moore once astutely pointed out, myths need a Ragnarok, and without the hard defining line of an ending (at least until the grandchildren of the Bushes and Clintons are running for office), there’s no real way to judge whether Jessica’s rambling, discursive adventures are more or less than the sum of their dream-logic parts. So for every powerful image, like the Paperhouse-esque silhouette/villain/father or the little French band that plays in Jessica’s shower, there’s something that seems a bit on the nose without further explanation or exploration, like the cute li’l monkey getting stabbed to death or a room full of giant fetus-babies with their eyes gouged out and tongues pulled out. Without the constant an ending would provide, the equation is unsolvable. Of course, we wouldn’t even be discussing these challenging topics if the comic were not an experiment to begin with.

Carnival of souls: special derailment edition

April 8, 2008* First we learned that Lionsgate was pushing back the release of the upcoming Clive Barker adaptation The Midnight Meat Train. Then (i.e. this morning) we find out that they may have once again shortened the title to the Pips-esque Midnight Train (prompting hyuk-hyuk approval from the same doof who was baffled by what The Ruins was about.) And now we discover that, meaty or meatless, it’s going straight to DVD. For crying out loud.

* Here’s another bummer: Ed Brubaker, Matt Fraction, and David Aja, the founding creative team of The Immortal Iron Fist—the best superhero comic of 2007—are leaving the book.

* B-Sol at the Vault of Horror serves up another of his sharp overviews of horror-movie history. This time he’s kicking off a series of posts on the modern zombie movie with a look at the early years of the genre, starting with its foundational text, George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, and the “rules” for zombie behavior it established.

* And here’s the first of a weekly series of interviews with Battlestar Galactica writer/producer Mark Verheiden over at ComicMix. Okay, I feel a little better about life now.

Carnival of souls

April 7, 2008* Let’s get started with some Clive Barker beefcake, shall we?

(Via Dread Central.)

* And let’s follow it up with some Frank Quitely Batman and Robin, why don’t we?

(Via Newsarama.)

* Back to Barker for a second, you kind of had to see this coming when their screenplay got shelved in favor of one from the people who write the Saw sequels, but French director duo Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury are now officially no longer directing the Hellraiser remake. The Weinsteins’ horror-movie reign of terror continues. (It’s a good thing Jason Adams was taking the day off.)

* I have good news and bad news about the new, decade-in-the-making Portishead album. The bad news is that there are no beats, and that’s a huge letdown. But the good news is that band members Adrian Utley and Geoff Barrow are talking about director John Carpenter’s work as a film score composer.

* In recent months I’ve talked a bit about how the video game tropes we take for granted are actually incredibly bizarre and merit examination and exploration, perhaps even within the framework of narrative fiction a la Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim books. Because I don’t actually play video games and therefore don’t know what the hell I’m talking about, it never even occurred to me to think about this in terms of not just weird story/worldbuilding elements (a star makes you invincible, you fight turtles and mushrooms, etc.) but also in terms of the mechanics of gameplay itself. Why should you be able to climb walls and ceilings as easily as walking? Why, when you have a rocket launcher, can you not open certain doors without a particular key? Why does just touching certain objects instantly kill you? God bless the Internet, and reader kiss the next few hours goodbye, because the TV Tropes wiki has an absurdly comprehensive and well-written list of every video game trope you can think of. Besides being both funny and nostalgic, it’s actually quite eye-opening if you haven’t thought about this stuff in this way before. (I found this via Nate Patrin at Joystick Division, who lists some of his favorites.)

* Finally, I only have one word to say about this unique Lost recap (via Jim Treacher)…what?

Comics Time: Tekkon Kinkreet: Black and White

April 7, 2008Tekkon Kinkreet: Black and White

Taiyo Matsumoto, writer/artist

Lillian Olsen, translator

Viz, September 2007

624 pages

$29.95

Perhaps the most fascinating thing about Taiyo Matsumoto’s Tekkon Kinkreet is how its art constantly draws attention to its nature as art yet never compromises the totality of the story’s vision. Like a Gahan Wilson cartoon or Klaus Voorman’s cover for the Beatles’ Revolver, Matsumoto’s shaky—I almost wanna say gawky—line reveals itself as the product of a hand committing ink to paper on every page. Its largely uniform weight draws the eye to every detail at once, momentarily disabling the part of our brain that tricks us into seeing comics pages as three-dimensional environments rather than an assemblage of flat shapes, at least until Matusmoto’s skillful spotting of blacks (holy moses, check out page 538!) once again guides us back into the illusion.

Step back for a wider view and the gangly linework fits neatly with the spindly, frequently scarred characters, and the messy city they inhabit, most often viewed from the ground up like a lost child would see it. There’s a weakness to the art that is again reinforced by the story: On a certain level it’s a futuristic, dystopian crime-action thriller about rival factions (cops, street gangs, yakuza, a sinister religious/entertainment corporation, and two feral kids named Black and White) battling for control of a sprawling city called Treasure Town. But while the action is thrilling–and, refreshingly enough for a translated manga with a potentially byzantine plot, easy to follow–where the book really hits home is on an emotional level. Its elegiac feel is perhaps meant to recall real-world analogues like the Disneyfication of New York City, but for me it functions as a message about caring for people and things who are past caring for themselves. It’s defined by relationships between people who end up making themselves emotionally vulnerable and yoked to a belief in something better at great risk to themselves–streetwise Black’s love for his idiot-savant brother White, White’s love for his increasingly brutal brother Black, crimelord the Rat’s desire to preserve the city he’s mostly just stolen from, the cops’ desire to preserve even the criminal underclass against an encroaching and even more vicious modernity. Now, as someone who’s gotten a lot more enjoyment out of Disneyfied Times Square than Taxi Driver Times Square, many of the book’s more didactic moments and gangster poses fall flat with me. But there’s a part of everyone that still pines for wild youth, warts and all.

In the end almost all the characters are forced to choose the things that are most important to them and move on, leaving the rest behind, which is essentially how the process of growing up works. It’s a coming of age tale that actually feels like coming of age does. I’m really impressed by how slowly and naturally these themes unfold, too–Matsumoto has a grasp on pacing that makes this serialized work read just great in a collected edition. It’s all packed into a well-designed, hefty softcover, the kind of book that begs to be given as a gift or passed from reader to reader. Recommended.

The Uplift Mofo Movie Plan

April 6, 2008I’m sure it says something about me that with the exception of Doomsday—Doomsday!–I can’t remember the last time I went to a movie that made me feel good. I’m talking about feeling good thanks to what happens in film, of course, not the film’s quality. I’ve certainly seen plenty of good and even great movies in recent months, movies that make me feel good the way all great art does. But the vast majority of films I’ve chosen to see in the theater since 2005–this includes The Ruins, Rambo, Cloverfield, The Mist, I Am Legend, No Country for Old Men, There Will Be Blood, Eastern Promises, Hostel Part II, 28 Weeks Later, Children of Men, Pan’s Labyrinth, The Host, King Kong, A History of Violence, War of the Worlds, and Land of the Dead–are about making the audience feel the emotional effects of cruelty, brutality, violence, and despair in some combination or other. Checking my review-link sidebar over on the lefthand side of the page I see that I also saw some movies that are slightly less interested in making one feel awful, like Dragon Wars and Grindhouse and Shoot ‘Em Up, but they were too crappy to make me leave the theater whistling a happy tune, and at any rate I’m stretching it with Grindhouse, while Shoot ‘Em Up is in many ways more bothersome than your average torture-porn flick, and needless to say all three were violent. Hell, even my feel-good flick contained a viral semi-apocalypse and dismemberments galore, while the most recent one before that was 300, which is in the same boat.

Looking back on all those movies, I would guess that becoming a horror blogger has influenced what I consider to be “must-sees” in the theater. And hey, that’s fine. Back when I did my first horrorblogging marathon while this was still mostly a comics blog, I very consciously was trying to reconnect with the genre that had given me so much enjoyment as I discovered it late in high school and throughout college. Making this a full-time horror blog was done with that in mind as well. I mean, I like being the guy with a Hellraiser T-shirt on at opening night of Cloverfield. I like being the guy my friends and co-workers turn to when they want an “authoritative” opinion about the adaptation of The Mist or I Am Legend. Moreover, I simply enjoy seeing movies in the theater. It’s one of my favorite things to do, and since horrorblogging (for me at least) is largely a subset of filmblogging, I do it a lot now, which is great.

But there have been times recently when the lights go down and the trailers roll and the opening credits finally start and I wonder to myself what it would feel like to have this experience knowing that I’m not going to see people get brutally killed in the next 90 minutes. I’ve actually forgotten!

Carnival of souls

April 5, 2008* I saw and reviewed The Ruins today.

* And while we’re on the subject, Bruce Baugh reviews The Ruins author Scott Smith’s first novel, A Simple Plan. I haven’t read the book so I’m skittish about reading the whole review, but I got a lot out of Bruce’s opening paragraphs regarding differing approaches to moral criticism in fiction.

* Here’s a character breakdown for the upcoming Battlestar Galactica prequel Caprica which I will be trying to avoid spoilers on so I’m not reading it but you can if you want and I won’t judge you.

* In one of her all too infrequent geekblogging breakouts, Eve Tushnet tackles a slew of horror films: Audition, May, Session 9, Ringu, and The Ring. Regarding those last two, like most people she prefers the version she saw first, but for a different reason than I’ve ever seen anyone cite before.

* Chris Butcher continues to refer to the Geoff Johns/Grant Morrison/Greg Rucka/Mark Waid/Keith Giffen/cast of thousands weekly series 52 with words like “pablum,” and I continue to be baffled by this given how clearly, even ostentatiously weird, idiosyncratic, and follow-your-bliss its peripatetic plot and themes were. Also, I liked the last issue of World War Hulk.

* This week’s Horror Roundtable is about out favorite writings on horror. Curt at Groovy Age takes issue with my citation of Noel Carroll’s The Philosophy of Horror, pointing out the way Carroll treats horror plotlines like mysteries in which the characters attempt to “solve” the horrific presence. (Kind of like the initial set-up of The Ring, now that I think about it.) The funny thing is I didn’t even REMEMBER the focus on “solving” the horror until Curt brought it up in this post. What resonated for me was Carrol’s emphasis on how horror violates our sense not just of safety (like a lion on the loose or a mugger would) but also our sense of normalcy and even sanity. That seems like such a key distinction between horror proper and other things that are just scary. I read TPoH at a time when I was searching for a theory to explain why images that didn’t present a physical threat to the character who sees them–the girls in The Shining are the best example–were still so scary. This was an issue the prevailing Carol Clover-driven horror-film theories couldn’t account for.

* Finally, this shit is bananas, B-A-N-A-N-A-S: Frank Miller’s The Spirit, ladies and germs. Get ’em while they’re hot. (Shhhhh.)

Hollywood and vines

April 5, 2008I probably went into Carter Smith’s film adaptation of Scott Smith’s (no relation) The Ruins expecting too much. I don’t see how I could have avoided that given just how wonderfully written the novel was. Unless they were to get very lyrical with landscapes and objects and sound, a la No Country for Old Men or There Will Be Blood, there was simply no way the filmmakers could translate the book’s ferociously intense interiority to the screen. (Well, now that I think of it, that was a way, and it was a way they didn’t take.) They made a good movie, don’t get me wrong. If you haven’t read the great novel you might think they made a great movie. I’m not sure.

What they did is rely on the ability of their actors to perform pain, and whenever that was going on they succeeded in a big way. As I’ve said before, the casting of this film was a real coup. Each of the main characters is attractive not in a plastic MTV/CW way, but in a your-girlfriend’s-cute-best-friend or your-good-looking-roommate way. You’re instantly attracted to each not in the way you’re attracted to matinee idols or pin-ups, but to good-natured, presentable people in the prime of their lives. Perhaps that’s why the necessarily truncated intro—which collapses our American foursome’s meeting and befriending of German tourist Matthias and a group of party-hardy Greeks and their subsequent decision to set out to an off-the-map Mayan ruin to track down Matthias’s brother and his newfound archaeologist lady friend from days into literally minutes—doesn’t feel nearly as rushed as it probably ought to. If I bumped into any of these people on vacation, I’d probably go offroading with them too. (Certainly I defy you not to come away from this movie with a crush on Jena Malone, if you’re oriented in that direction.)

The cutting and splicing doesn’t start to hurt until they reach the ruins, where a series of decisions made by the Smiths (Scott wrote the screenplay as well as the novel) in the interest of economizing character and conveying the stakes as quickly as possible upset the complex, nuanced interplay that made the novel such a pleasurably unpleasant read. (I’m about to SPOIL THE HELL OUT OF THIS MOVIE, so be warned.) Instead of putting two and two together regarding how much business the Mayan guards mean via the discovery of the body of Matthias’s brother, the movie gets the point across by having the Mayans kill the Greek right away. With him down, it’s left to Matthias to become the outsider figure who breaks his back in an ill-fated descent down the ruins’ shaft. So not only do we lose the pathos of a mortally wounded character whom the language barrier has rendered completely isolated (the Greek), we also strip ersatz group leader Jeff of his other competent counterpoint (Matthias), whose calm and melancholy works in strange harmony with Jeff’s frustration and angry optimism in the novel.

Then, for reasons less immediately apparent, Stacy and Eric swap roles so that it’s she who becomes infested with the killer vine and subsequently falls apart at the seams. This switch has the unfortunate effect of producing a far more stock character—the hysterical female, the Barbara from Night of the Living Dead—than what we had in the book. It also creates less of a contrast between Jeff and Eric, so now instead of a sullen MacGyver and an OCD self-mutilator we’ve got two shades of macho, one simply less take-charge than the other.

But let’s get back to the good—the suffering. It’s palpable and at times hard to watch. Though essentially asked to embody a cliche, Laura Ramsey as Stacy in particular is extraordinary. As with Malone, her body is used astutely by the filmmakers first to entice and then to unnerve with its soft, all-underbelly physicality. Her screams and sobs during the scene in which her friends finally take a knife to her to try to extract the infestation are so gutwrenchingly convincing I literally almost started crying myself out of sheer sympathy. Shortly thereafter she’s asked to carry the biggest gore effect in the film and aces it with understatements and false bravado, which quickly give way to utter (and utterly believable) despair. Malone is mostly her support throughout, but she’s quite good at it, repeatedly drawing on childlike gestures (hand-holding, hugging). And the person-on-person gore is as unflinching as you’ve heard, as raw as David Cronenberg’s recent crime movies.

What about Jeff, though? In the novel his was one of the most unique survival-horror characters I’d ever seen: He got more and more on top of his game as events progressed, as though on fire with the knowledge that his whole life had led him to this moment—yet he became less and less likable as this happened, and he knew it, and he still couldn’t do anything about it. (Along with Will Smith’s competent-to-the-point-of-neurosis Robert Neville in Francis Lawrence’s I Am Legend, Jeff was one of two fascinating riffs on the Survivor Type I came across last year.) Actor Jonathan Tucker has a hangdog handsomeness, a weary beauty, that lights him from within as he plays out Jeff’s ever-increasing level of no-nonsense decision making. The problem is that he’s not playing it out against anything. The aforementioned changes to the characters and their relationships gives him less to work with. Meanwhile the novel’s relentless emphasis on quotidian physical deterioration (as opposed to the menace of the vines or even just the Mayans)—thirst, sunburn, filth, starvation, heat, aches and pains, the need to find and conserve food and water and pain medication—is almost completely eliminated from the film beyond a few token shots of rationed grapes and swigs from a water bottle. What I missed most of all is the characters’ use of booze: The fact that the Greek packed more tequila than water, Eric Stacy and Amy repeatedly getting drunk despite knowing it will help kill them, and most importantly Jeff (and Matthias)’s reaction to their drunken stupidity. With none of those factors there to test him, we don’t really feel Jeff’s pain over knowing he’s got to be good enough to survive on behalf of the whole group.

Which leads us to the end of the film, the most rushed part of the whole movie. It deviates significantly from the novel, which is fine in principle, and could have even worked in practice. But since they couldn’t depict Jeff’s struggles throughout, they condense it into an incongruous “his name was Robert Paulson” speech to the Mayans that feels grafted from a different movie and makes Jeff’s sacrifice feel like it was done out of a kind of shakily established chivalry rather than fatigued rage. The penultimate sequence is straight out of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre or The Descent, a nice bookend to the Shining riff of the opening credits. But given what we know of the vines’ epidemiology, this development has eschatological repercussions that are completely unexplored. Instead we get a coda involving the remaining Greeks that cuts so quickly to the closing credits and their mood-killing Yeah Yeah Yeahs music that it’s almost like the movie had a plane to catch or something. I understand the filmmakers’ need to shorten a marathon to a steeplechase, but not this breakneck sprint to the finish line.

Part of me wishes I’d gone into the movie sight-unseen, like all those Ain’t It Cool reviewers. I probably would have remained mightily impressed by the performances and by Carter Smith’s taut, smart shots. I doubt I’d have felt the cuts and the rush, and I probably would have gone and read the book afterwards anyway. Coulda woulda shoulda.

Ruins reax

April 4, 2008Jason Adams reads my mind and posts about the bizarre reaction to The Ruins by all of Ain’t It Cool News’s reviewers. (Thanks for saving me the work, man!) Basically, they all loved it, but they were all totally stunned by this because they assumed it would suck. I’ve seen similar bafflement about the movie expressed on some of the big horror sites–statements like “I just have to know what the hell is going on. Hopefully I won’t be disappointed when all is revealed.” If only it were based on an acclaimed novel available at your local library!

My friend Jim Treacher wrote me to say he was nervous that the studio wasn’t screening the movie for critics. But can you blame them? If the CW among genre-centric reviewers, who really ought to know better, was that it was gonna stink, what do you think your average mainstream-media critic would make of it? After all, it’s about violent and horrible things happening to attractive young people–unless you can cobble together a metaphor for the Bush Administration’s treatment of Latin America out of it, it must be garbage, right?

Comics Time: Planetes Vols. 1-3

April 4, 2008Planetes Vols. 1-3

Makoto Yukimura, writer/artist

Yuki Nakamura, translator

Anna Wenger, adapter

Tokyopop, 2003-2004

Volume 1: 240 pages

Volume 2: 268 pages

Volume 3: 240 pages

$9.99 each

Originally written on July 1st, 2004 for publication in The Comics Journal

The unending torrent of translated manga titles is all too easy for a reader raised on American comics to drown in. Unfamiliar and therefore arbitrary-seeming conventions, countless -makis, -muras, and other seemingly interchangeable surnames, and that damned right-to-left flow: It’s enough to cause Western eyes to glaze over. It’s gotten to the point where an exasperated sigh of “I just don’t get manga” is viewed as an acceptable assessment in some circles. Indeed, “It’s all speed-lined, Japanophilic crap starring giant robots and big-titted doe-eyed schoolgirls in their panties” has assumed a place of (dis)honor right along side “It’s all mindless, sexist, crypto-fascist adolescent power fantasies about men in tights hitting each other” (mainstream/superhero/genre comics) and “It’s all pointless, self-obsessed, navel-gazing slice-of-life stories about pathetic white guys feeling sorry for themselves” (alternative/underground/art comics) in the pantheon of stupidly dismissive sequential-art stereotypes.

Enter Makoto Yukimura’s Planetes, the antidote to conventional wisdom about what translated manga can be, and the perfect gateway drug for fans of American art- and genre-comics alike. Compelling characters, story, and art add up to one of the finest regularly published titles you’re likely to come across on the racks today, from any country.

Working within the type of hard science-fiction framework not often seen in genre comics, Planetes takes place in the semi-near future, a time when orbital space stations bustle with civilian activity, the moon has been colonized, Mars is on its way to being so, and a manned expedition to Jupiter is on the horizon. The high volume of space travel has given rise to unforeseen, space-borne growth industries, the least glamorous of which is debris pick-up. Glorified garbagemen travel through low Earth orbit, picking up busted satellites, wreckage from shuttle accidents, discarded refuse, and other space junk before it can collide at high velocity with unwary travelers.

From this SF premise, writer/artist Makoto Yukimura (ably assisted by the nearly invisible adaptation work of Anna Wenger) spins something pretty close to magic. The key–and it’s so simple it’ll make you kind of angry that every writer doesn’t employ it–is that the action stems not from the external dictates of plotting or the need to get across some “mad idea” aimed at knocking the metaphysical socks off the reader, but springs organically from the internal workings of the characters themselves. And what characters they are.

We’re first introduced to Yuri, an astronaut of Russian decent, in a full-color flashback, on board a passenger space flight with his wife. Even this very first scene is peppered with the alarmingly perceptive moments that make the series so memorable: Yuri’s wife carries a compass with her every time she travels through space, in order to remember that even in the directionless void, there’s a direction home. It’s the sort of short, sharp shock of instant insight and attachment that makes the ensuing, slow-motion catastrophe all the more wrenching to watch, as does Yakimura’s jarring change in perspective from an extreme, speed-blurred close-up to a cold, impersonal long shot. The accident that claims Yuri’s wife’s life was caused by the type of debris storm that Yuri, in his new career as a debris clearer, seeks to prevent, though his stoicism is complete enough to hide this true, tragic motivation even from himself.

Yuri’s crewmate Fee is a much less quiet sort. A chain-smoking American woman of the sort some space-age Guess Who might sing about, Fee is the Bones McCoy of the hauler’s crew. Her deadpan, take-no-shit refusal to indulge the melancholy reveries of her shipmmates makes her not just a natural foil for the sensitive Yuri and the moody Hachimaki (crew member number three), but a literal lifesaver given the mental duress contact with the vastness of space can engender. As if to contrast Fee’s level-headedness with the space-shot flakiness of the other main characters, Yakimura assigns her the series’ single most heroic act–preventing the destruction by terrorists of an entire space station, which in turn would generate enough debris to effectively end space travel for years. Fee’s heroism, however, derives not from some high-minded belief that man is meant for the stars, but from a jones for the cigarettes available for sale on the space station. It’s not idealism that motivates Fee–it’s a nic fit.

The aforementioned Hachimaki initially strikes the reader as the book’s shallowest, least-interesting character. Hachimaki may be a garbageman, but his ambition to be something more is clear. It’s alternately expressed as a desire to own his own spaceship (a luxury item even in this era of lunar cities) and an obsession with becoming a crew member on the first, years-long manned trip to Jupiter. By now readers familiar with the conventions of manga characterization may be rolling their eyes: The young man who works relentlessly to become the best in his chosen field is a staple of shonen stories, from your standard martial-arts adventures to the culinary competitors of Iron Wok Jan. And of course, you don’t need to be a manga devotee to know that The Brash, Tow-Headed Rookie With Something To Prove is a well-trod road indeed.

But as Hachimaki moves to the forefront, eventually becoming the lead character of the later volumes, we’re stunned to see the emergence of a genuinely complex and conflicted character. There’s nothing conventional at all about Hachimaki’s near-pathological desire to prove his emotionless self-sufficience to anyone who cares to notice. The emptiness of space–which in one of Volume One’s most harrowing sequences nearly cripples the still-inexperienced astronaut–is both the perfect nemesis for him to conquer and the perfect refuge in which he can hide from the emotional demands of interpersonal contact. It’s this that Hachimaki finds more frightening than the risks of space travel, in which humans are after all little more than glorified debris themselves.

Yukimura’s ability to slowly coax out the emotional core of his lead character lies not just in his expertise in shaping Hachimaki himself, but in the gorgeous sensitivity with which he peppers the story with memorable supporting players who naturally elicit moving and riveting responses from the upstart astronaut. There’s Mr. Rowland, the aging astronaut who’d rather abandon himself to the ravages of the lunar desert than die Earthside. There’s Nono, the lunar-born girl whose emotional strength exceeds that of her low-G-weakened physiology. There’s Hachimaki’s family: His father, the head-in-the-clouds veteran astronaut; his brother, the cool, single-minded amateur rocket scientist (seriously); his mother, whose love for her family is constantly tested by their passion for being thousands of miles away from home. There’s Hakimu, the anti-colonization terrorist (the other big growth industry of the era) whose initial refusal to kill Hachimaki is more devastating to the young explorer than his eventual change of heart. There’s Sally, the captain of Hackimaki’s Jupiter-bound crew whose last-ditch attempt to snap him out of his malaise is equal parts touching, hilarious, and (well) hot. Last and certainly not least there’s Tanabe, Hachimaki’s successor aboard the debris hauler and the woman whose belief in a thing called love becomes more attractive to Hachimaki the more infuriatingly naïve he finds it.

But the real miracle of Planetes is that its indelible characters are matched by unforgettable imagery. “Visual poetry” is how I’ve heard it described, and that nails it as well as any description can. Yukimura’s style is already more realistic and appealing than many of his counterparts’, but he adds to this an almost uncanny ability to produce both individual moments and entire sequences of stunning visual impact. Volume Three’s finest moments come when a white cat, embodying Hachimaki’s conflicting desires for death and love, directly addresses the viewer (in place of Hachimaki himself), its white tail coiling and swaying against the black void so vividly as to be nearly animate. Volume Two offers another demonstration of Yukimura’s skill with contrast: As Hachimaki nearly drowns following a motorcycle accident back on Earth, he’s drawn as a reverse negative–fluid, minimalist white lines against a black background. The effect, amidst Yukimura’s rich realism and almost colorful graytone, is as startling as the accident itself. And it’s not just extreme mental states that Yukimura evokes with panache: His splash pages of lunar landscapes and extraterrestrial vistas immediately bring to mind the vivid, alien beauty of Kubrick’s 2001, or the powerful contrast between man and nature of a Ford or Leone. Meanwhile his simple character work is just as memorable. Two standout moments come from Volume Three: Tanabe grinning as the wind blows through both her hair and the beautiful array of windmills behind her, and Tanabe’s father on stage during his punk-rock filth-and-fury heyday. The last time I saw the heart-rending loveliness of a happy, beautiful woman and the super-fuckin’-funness of rock and roll depicted this convincingly, I was reading Love and Rockets.

Is that a fair comparison to make? I think it just might be. Literate comics fans have, I think, been conditioned to ignore the kinds of books put out by the American manga-publishing giants like Tokyopop and Viz; they’ve convinced themselves to stick with the Tezukas and Miyazakis and Tsuges, or to pine wistfully after a vaguely defined glut of Good Stuff They’re Never Gonna Translate. But do yourself a favor. Elbow your way past the TRL-watching kids lined up in front of the manga racks at the bookstore. It’s an unlikely place to renew your faith in comics, I know, but if you pick up the sturdy, gray-spined volumes of Planetes you find there, that’s exactly what this emotional, beautiful series will do.

Carnival of souls

April 3, 2008* I’d say “God damn it,” but maybe that was the problem: Cowboys for Christ, Robin Hardy’s Christopher Lee-starring follow-up to The Wicker Man, has been shut down due to lack of funds.

* Looks like Guillermo del Toro really will be directing the Hobbit movies. Did I mention that Hellboy and Pan’s Labyrinth were not good? Because they were not good. (Via Jason Adams.)

* Reverence brigades be warned: Frank Miller is going all Sin City on The Spirit‘s ass! (Via Kevin Melrose.)

* Finally, Slant Magazine’s Jeremiah Kipp offers up a lengthy, thoughtful review of one of my all-time favorite films, David Lynch’s Lost Highway.